George MacDonald facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George MacDonald

|

|

|---|---|

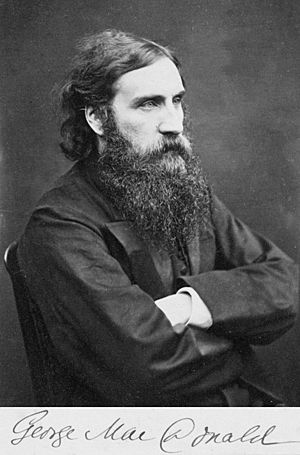

MacDonald in the 1860s

|

|

| Born | 10 December 1824 Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland |

| Died | 18 September 1905 (aged 80) Ashtead, Surrey, England |

| Occupation | Minister, writer (poet, novelist) |

| Nationality | Scottish/British |

| Alma mater | University of Aberdeen |

| Period | 19th century |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

Louisa Powell

(m. 1851) |

George MacDonald (born December 10, 1824 – died September 18, 1905) was a Scottish author, poet, and Christian minister. He was a very important person in creating modern fantasy literature. He also helped and guided other writers, like Lewis Carroll. Besides his famous fairy tales, MacDonald wrote many books about Christian beliefs.

Many well-known authors have said that George MacDonald's writings greatly influenced them. These include Lewis Carroll, J. M. Barrie, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Neil Gaiman.

C. S. Lewis once said that MacDonald was his "master." Lewis explained that after reading MacDonald's book Phantastes, he felt like he had "crossed a great frontier." G. K. Chesterton also said that The Princess and the Goblin changed his "whole existence."

Even Mark Twain, who at first didn't like MacDonald, later became his friend. There is some proof that Twain was influenced by him too.

Contents

His Early Life

George MacDonald was born on December 10, 1824, in Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. His father was a farmer. His family was connected to the MacDonalds of Glen Coe, a group that faced a terrible event in 1692.

George grew up in a family that loved to read and learn. One of his uncles was a famous expert in Celtic languages. He collected fairy tales and old Celtic poems. His grandfather supported publishing old Celtic texts. His step-uncle was an expert on Shakespeare. Both his parents loved books. His mother even had a classical education and knew many languages.

As a child, George often had health problems. He suffered from lung issues like asthma and bronchitis. He also had tuberculosis, a serious illness that affected many in his family. His mother, two brothers, and later three of his own children died from it. Even as an adult, he often traveled to find cleaner air for his lungs.

MacDonald grew up in the Congregational Church. This church had strong beliefs, including Calvinism. However, his family was quite unique. His grandfather was born Catholic but became a Presbyterian elder. His grandmother was a church rebel. His mother's brother was a Gaelic speaker who became a church leader. His step-mother was the daughter of an Episcopalian priest.

In 1845, MacDonald finished his studies at the University of Aberdeen. He earned a master's degree in chemistry and physics. For a few years, he thought deeply about his faith and what he wanted to do with his life. His son, Greville MacDonald, who wrote about his father's life, believed George might have become a doctor. But he thought a lack of money stopped this plan. In 1848, MacDonald began training to become a minister.

Becoming a Minister

In 1850, George MacDonald became a minister at Trinity Congregational Church in Arundel. Before that, he worked briefly in Ireland. However, his sermons caused some disagreements. He preached that God's love was for everyone. He also said that everyone could find goodness. Because of these ideas, his salary was cut in half.

In May 1853, MacDonald decided to leave his job as a pastor in Arundel. Later, he worked as a minister in Manchester. He left that job too because of his poor health. A friend, Lady Byron, suggested he travel to Algiers in 1856. She hoped the warmer climate would help his health. When he returned, he settled in London. He taught for a while at the University of London. MacDonald also worked as an editor for a children's magazine called Good Words for the Young.

His Writing Career

George MacDonald's first novel, David Elginbrod, was published in 1863. He is often called the "founding father" of modern fantasy writing.

Some of George MacDonald's most famous books are Phantastes, The Princess and the Goblin, At the Back of the North Wind, and Lilith. These are all fantasy novels. He also wrote many popular fairy tales, such as "The Light Princess" and "The Golden Key".

MacDonald once wrote about his audience: "I write, not for children, but for the child-like, whether they be of five, or fifty, or seventy-five." This means he wrote stories that anyone with a childlike wonder could enjoy. He also published books of sermons, even though being a pastor wasn't always easy for him.

After becoming a successful writer, MacDonald went on a lecture tour in the United States. This was in 1872–1873. He was invited by a company called the Boston Lyceum Bureau. On this tour, MacDonald gave talks about other poets like Robert Burns and Shakespeare. He was very popular, speaking to crowds of about three thousand people in Boston.

MacDonald was a guide and friend to Lewis Carroll. Carroll's real name was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. It was MacDonald's advice that helped Carroll decide to publish Alice. MacDonald's many children loved the story, which encouraged Carroll. Carroll was also a great photographer. He took many pictures of MacDonald's children.

MacDonald was also friends with John Ruskin. He helped Ruskin in his long attempt to win the heart of Rose La Touche. While in America, MacDonald became friends with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Walt Whitman.

MacDonald used fantasy stories to explore what it means to be human. This greatly influenced many famous authors. These include C. S. Lewis, who even included MacDonald as a character in his book The Great Divorce. Lewis said that MacDonald's religious teachings were very important to him. He felt MacDonald was very close to the spirit of Christ.

Other writers influenced by MacDonald include J. R. R. Tolkien and Madeleine L'Engle. MacDonald also wrote realistic novels about Scotland. These books helped start a style of Scottish writing called the "kailyard school."

Chesterton said that The Princess and the Goblin showed him "how near both the best and the worst things are to us." It made everyday things like staircases and doors seem magical.

Later Life

In 1877, George MacDonald received a special pension from the government. In 1879, he and his family moved to Bordighera, Italy. This area, called the Riviera dei Fiori, was a favorite spot for British people living abroad. It was near the French border. There was an Anglican church there, which he attended.

MacDonald loved the Riviera. He spent 20 years there and wrote almost half of all his books during that time. Many of his fantasy works were written here. He started a literary studio in Bordighera called Casa Coraggio, which means "Bravery House." It became a famous cultural center. Many British and Italian travelers visited. They held plays and readings of works by Dante and Shakespeare.

In 1900, he moved into a house called St George's Wood in Haslemere, England. His son, Robert, designed the house. His oldest son, Greville, oversaw its construction.

George MacDonald died on September 18, 1905, in Ashtead, Surrey, England. His body was cremated in Woking, Surrey. His ashes were buried in the English cemetery in Bordighera, Italy. His wife Louisa and daughters Lilia and Grace are buried there with him.

His Family Life

MacDonald married Louisa Powell in Hackney in 1851. They had eleven children together. Their children were Lilia Scott, Mary Josephine, Caroline Grace, Greville Matheson, Irene, Winifred Louise, Ronald, Robert Falconer, Maurice, Bernard Powell, and George Mackay.

His son Greville became a well-known doctor. He also wrote many fairy tales for children. Greville made sure that his father's books were published again. Another son, Ronald, became a novelist. His daughter Mary was going to marry the artist Edward Robert Hughes but she died in 1878. Ronald's son, Philip MacDonald, who was George MacDonald's grandson, became a Hollywood screenwriter.

Sadly, tuberculosis caused the death of several family members. This included Lilia, Mary Josephine, Grace, and Maurice. One of his granddaughters and a daughter-in-law also died from it. MacDonald was especially sad about the death of Lilia, his oldest child.

There is a blue plaque on his home at 20 Albert Street, Camden, London. This plaque shows that a famous person once lived there.

His Beliefs

George MacDonald's beliefs focused on God as a loving Father. He wanted people to feel a connection to God and Christ. He believed this could happen by reading the Bible and seeing God in nature.

MacDonald believed that everyone would eventually turn to God and be reunited with Him. This is not the idea that everyone is automatically saved. Instead, it's that all people will eventually choose to change and return to God.

MacDonald never felt comfortable with some parts of the Calvinist church's teachings. He felt that some of their ideas were "unfair." For example, when he first learned about the idea of predestination, he cried. This idea suggests that God has already chosen who will be saved. MacDonald later wrote novels that showed he disliked the idea that God's love was only for some people.

MacDonald believed that God does not punish people just to be angry. He thought that God's anger is meant to help people become better. He believed that just as a doctor might use strong treatments to heal a serious illness, God might use difficult experiences to heal a person's spirit. MacDonald said, "I believe that no hell will be lacking which would help the just mercy of God to redeem his children." He believed that God's love would eventually make people truly good.

Published Works

Fantasy Books

- Phantastes: A Fairie Romance for Men and Women (1858)

- "Cross Purposes" (1862)

- The Portent: A Story of the Inner Vision of the Highlanders, Commonly Called "The Second Sight" (1864)

- Dealings with the Fairies (1867), including "The Golden Key", "The Light Princess", and "The Shadows"

- At the Back of the North Wind (1871)

- Works of Fancy and Imagination (1871), including Within and Without, "Cross Purposes", "The Light Princess", and "The Golden Key"

- The Princess and the Goblin (1872)

- The Wise Woman: A Parable (1875) (also known as "The Lost Princess" or "A Double Story")

- The Gifts of the Child Christ and Other Tales (1882)

- The Day Boy and the Night Girl (1882)

- The Princess and Curdie (1883), a follow-up to The Princess and the Goblin

- Lilith: A Romance (1895)

Other Novels

- David Elginbrod (1863)

- Adela Cathcart (1864); contains many fantasy stories told by characters

- Alec Forbes of Howglen (1865)

- Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood (1867)

- Guild Court: A London Story (1868)

- Robert Falconer (1868)

- The Seaboard Parish (1869), a follow-up to Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood

- Ranald Bannerman's Boyhood (1871)

- Wilfrid Cumbermede (1871)

- The Vicar's Daughter (1871), a follow-up to Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood

- The History of Gutta Percha Willie, the Working Genius (1873)

- Malcolm (1875)

- St. George and St. Michael (1876)

- Thomas Wingfold, Curate (1876)

- The Marquis of Lossie (1877), the second book of Malcolm

- Paul Faber, Surgeon (1879), a follow-up to Thomas Wingfold, Curate

- Mary Marston (1881)

- Warlock o' Glenwarlock (1881)

- Weighed and Wanting (1882)

- Donal Grant (1883), a follow-up to Sir Gibbie

- What's Mine's Mine (1886)

- Home Again: A Tale (1887)

- The Elect Lady (1888)

- A Rough Shaking (1891)

- There and Back (1891), a follow-up to Thomas Wingfold, Curate

- The Flight of the Shadow (1891)

- Heather and Snow (1893)

- Salted with Fire (1896)

- Far Above Rubies (1898)

Poetry Books

- Twelve of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis (1851)

- Within and Without: A Dramatic Poem (1855)

- "A Hidden Life" and Other Poems (1864)

- "The Disciple" and Other Poems (1867)

- Exotics: A Translation of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis, the Hymn-book of Luther, and Other Poems from the German and Italian (1876)

- Dramatic and Miscellaneous Poems (1876)

- Diary of an Old Soul (1880)

- A Book of Strife, in the Form of the Diary of an Old Soul (1880)

- The Threefold Cord: Poems by Three Friends (1883)

- The Poetical Works of George MacDonald, 2 Volumes (1893)

- Scotch Songs and Ballads (1893)

- Rampolli: Growths from a Long-planted Root (1897)

Non-Fiction Books

- Unspoken Sermons (1867)

- England's Antiphon (1868, 1874)

- The Miracles of Our Lord (1870)

- Cheerful Words from the Writing of George MacDonald (1880)

- "Preface" (1884) to Letters from Hell (1866) by Valdemar Adolph Thisted

- The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke: A Study With the Text of the Folio of 1623 (1885)

- Unspoken Sermons, Second Series (1885)

- Unspoken Sermons, Third Series (1889)

- A Cabinet of Gems, Cut and Polished by Sir Philip Sidney; Now, for the More Radiance, Presented Without Their Setting by George MacDonald (1891)

- The Hope of the Gospel (1892)

- A Dish of Orts (1893)

- Beautiful Thoughts from George MacDonald (1894)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: George MacDonald para niños

In Spanish: George MacDonald para niños