Juan Donoso Cortés facts for kids

Juan Donoso Cortés, Marqués de Valdegamas (born May 6, 1809 – died May 3, 1853), was an important Spanish writer, diplomat, and politician. He was also a Catholic thinker who wrote about politics and religion. He is known for his strong ideas against revolution and for supporting traditional values.

Quick facts for kids

The Most Illustrious

Juan Donoso Cortés, Marqués de Valdegamas

|

|

|---|---|

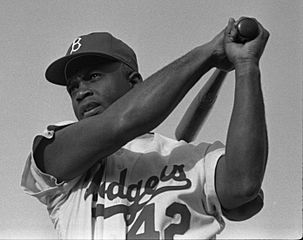

Portrait, 1849

|

|

| Born |

Juan Donoso Cortés

6 May 1809 Valle de la Serena, Spain

|

| Died | 3 May 1853 (aged 43) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

|

Notable work

|

Essays on Catholicism, Liberalism, and Socialism |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy

|

| School |

|

|

Main interests

|

Political theory, Political theology |

Contents

Life and Career

Early Years and Education

Juan Donoso Cortés was born on May 6, 1809, in a town called Valle de la Serena, in Spain. His father was a lawyer and landowner. Juan was tutored at home in subjects like Latin and French.

When he was 11, he went to the University of Salamanca for a year. Later, he studied at the Colegio de San Pedro de Caceres. At 14, he began studying law at the University of Seville, where he stayed until 1828. During this time, he started learning about philosophy. He was influenced by both liberal thinkers, who believed in individual freedom, and traditionalist thinkers, who valued long-standing customs and institutions.

After finishing his studies, Donoso worked for his father. In 1829, he became a professor of art and politics at the Colegio de San Pedro de Caceres. He was interested in Romanticism, a movement that focused on feelings and emotions. He also admired the Papacy (the Pope's role) and the Crusades, believing they brought energy to European society.

Starting in Politics and Journalism

In 1830, Donoso Cortés married Teresa Carrasco. Sadly, she passed away five years later after giving birth to their only child, Maria.

Around this time, Donoso entered politics. He was a strong liberal, meaning he supported more freedom and rights for people. After King Ferdinand VII died, Donoso supported the king's wife, Maria Christina, to become queen. Many liberals also supported her. However, the king's brother, Carlos, and his conservative supporters (known as Carlists) wanted Carlos to be king.

In 1832, Donoso wrote a paper supporting Maria Christina's right to the throne. Because of his efforts, the new queen appointed him to a position in the government.

When the First Carlist War began in 1833, Donoso spoke out against violence towards religious people in Madrid in 1834.

His views began to change after 1836, when soldiers forced Maria Christina to bring back an older, more liberal constitution. Donoso became a cabinet secretary and was elected to the Cortes (the Spanish parliament) as a member of the Moderate Party. This party represented middle-class interests and supported a king or queen with a constitution. He gave speeches praising this type of government but also said that sometimes a dictatorship (where one person has total power) might be necessary.

Donoso also wrote for various newspapers. He became more conservative during this time. He criticized some popular ideas and defended traditional religious practices. He believed that art should combine both classic and romantic styles.

Donoso understood how powerful newspapers were, but he also worried about how they could spread revolutionary or anti-Christian ideas. He thought that too much freedom of the press could lead to people losing their Christian values.

Becoming More Conservative

By the end of the First Carlist War in 1839, Donoso was disappointed with liberal ideas and the middle class. He became more private. When Maria Christina's rule ended, Donoso went to Paris from 1841 to 1843. There, he was strongly influenced by French traditionalist thinkers like Joseph de Maistre and Louis de Bonald.

Donoso returned to Spain in 1843 and helped Queen Isabella II gain full power. For his help, he became the Queen's private secretary and was given a noble title.

The Revolutions of 1848 across Europe, along with the death of his religious brother, made Donoso even more conservative. In January 1849, he gave a famous speech in the Cortes called "On Dictatorship." In this speech, he defended the government's actions to stop revolutionary activities in Spain. He strongly criticized the chaos he saw in Europe, saying that socialism (a political and economic theory) came from a loss of Christian values and a belief in no God.

Donoso later became critical of the prime minister, General Narvaez, and his speeches led to Narvaez's resignation. During this time, Donoso also briefly served as Spain's ambassador to Berlin.

Later Life and Important Works

In 1851, Donoso became the Spanish ambassador to France. He worked with Louis Napoleon, who later became Emperor Napoleon III. Donoso initially trusted Napoleon and might have helped him in his rise to power. However, they later found they had different ideas. Still, Donoso helped Napoleon's new government gain international recognition and represented Queen Isabella II at Napoleon's wedding.

During his last years, Donoso became very religious. He went on pilgrimages, wore a special shirt to show his devotion, volunteered to help the poor, and visited slums and prisons. He gave a lot of his money to charity. He also spent time writing against liberal Catholics in France.

His most famous work, Essays on Catholicism, Liberalism, and Socialism, Considered in their Fundamental Principles, was published in 1851. In this book, he argued that human philosophies alone cannot solve life's big problems. He believed that humanity depended completely on the Catholic Church for social and political well-being. He strongly criticized liberalism, saying it eventually led to atheistic socialism (socialism without belief in God).

In his final years, he exchanged letters with important people, including Queen Maria Christina and Pope Pius IX. He warned the Pope about threats from certain ideas like Gallicanism (a belief that the state has more power over the Church) and democracy. Many of his ideas were later included in Pope Pius IX's important writings.

Juan Donoso Cortés passed away in the Spanish Embassy in Paris on May 3, 1853. His remains were later moved to Madrid in 1900 and are now buried in the royal cemetery of San Isidro el Real.

His collected works were published in five volumes after his death.

Influence and Ideas

Juan Donoso Cortés had a lasting impact on political thought. The political philosopher Carl Schmitt praised Donoso in his book Political Theology (1922). Schmitt admired Donoso for understanding the importance of making clear decisions and the idea of sovereignty (supreme power or authority). Schmitt also believed that Donoso's speech "On Dictatorship" helped change the way people thought about history, moving away from the idea that history always progresses forward.

Donoso Cortés believed that true progress meant making human freedom better by connecting it to divine (Godly) principles. He worried that society had forgotten faith and instead focused on human reason, which he thought led to more problems. He felt that the Church's strong beliefs had saved the world from confusion by setting clear truths that should not be questioned.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Juan Donoso Cortés para niños

In Spanish: Juan Donoso Cortés para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |