First Carlist War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First Carlist War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Carlist Wars | |||||||

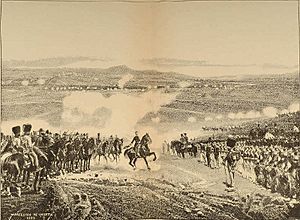

The Battle of Mendigorría, 16 July 1835 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

Supported by: |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

See list

|

See list

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Carlists: 15,000–60,000 | Liberals: 15,000–65,000 French: 7,700 British: 2,500 Portuguese: 50 |

||||||

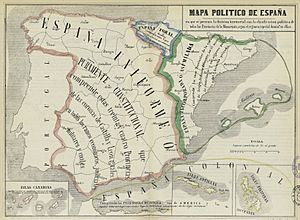

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain that lasted from 1833 to 1840. It was the first of three Carlist Wars. The war was fought between two main groups. One group supported Carlos de Borbón, the late king's brother. They were called the Carlists. They wanted Spain to return to a traditional, absolute monarchy. The other group supported Isabella II, the young queen, and her mother, Maria Christina, who was acting as regent. These supporters were called Liberals, cristinos, or isabelinos. They wanted a more modern, constitutional monarchy.

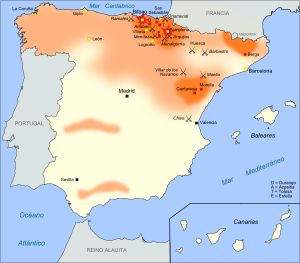

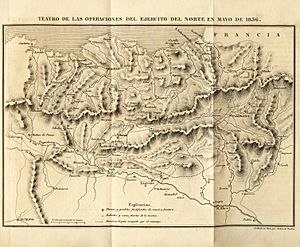

The main Carlist armies were in three different areas: the North, Maestrazgo, and Catalonia. These armies mostly fought on their own. There were also smaller Carlist groups that fought like guerrillas in mountain areas. These groups went as far south as La Mancha and Andalusia.

Besides being a fight over who should be king or queen, the war was also about how Spain should be governed. The Carlists wanted to bring back old traditions and regional laws. The Liberals wanted to defend a new system where the king or queen's power was limited by a constitution. Countries like Portugal, France, and the United Kingdom supported Maria Christina and Isabella II. They sent soldiers and money to help the Liberal side.

Contents

Why the War Started

At the start of the 1800s, Spain faced many problems. After the Peninsular War (a war against Napoleon's France), King Ferdinand VII returned to Spain in 1814. He got rid of the Spanish Constitution of 1812, which had been created during the war. He became an absolute king, meaning he had all the power. He also brought back the Spanish Inquisition, a powerful religious court.

Spain's economy was in trouble. The Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 had destroyed most of the Spanish navy. The Peninsular War had also damaged the country. Spain was losing its colonies in the Americas, which meant less money for the royal treasury. The government struggled to find solutions.

During a period called the Trienio Liberal (1820-1823), a more liberal government tried to fix the economy. They borrowed money from international bankers, especially the Rothschild family in London and Paris. Great Britain supported these liberal ideas and also had an interest in Spain's finances.

In 1823, other European powers helped Ferdinand VII regain his absolute power. He then refused to pay back the money the liberal government had borrowed. This caused problems with the Rothschilds for many years.

Towards the end of his life, King Ferdinand VII had no sons, only two daughters. In 1830, he made a special law called the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830. This law allowed his daughter, Isabella, to become queen after he died. This meant his brother, Carlos de Borbón, would not inherit the throne.

Carlos and his supporters tried to make Ferdinand change his mind. But Ferdinand stuck to his decision. When he died on September 29, 1833, Isabella became Queen Isabella II. Since she was only a child, her mother, Queen Maria Christina, became the regent. A regent rules for a child monarch.

Many people who supported absolute monarchy worried that Maria Christina would bring in liberal changes. They wanted Carlos to be king instead. They also disagreed about how much power the army and the Church should have. These disagreements led to the war.

The Spanish government, led by Maria Christina, needed money and support. They got a loan from the Rothschilds. This helped lead to the 1834 Quadruple Alliance. This alliance meant that Britain and France would protect the Spanish government and even send military help.

One historian explained that the war wasn't just about who had the right to the throne. It was also because many Spanish people wanted to return to an absolute monarchy. They believed this would protect their freedoms, regional identity, and religious traditions.

The war was very harsh. People on both sides were filled with anger. It was a fight where "brother fought against brother – father against son."

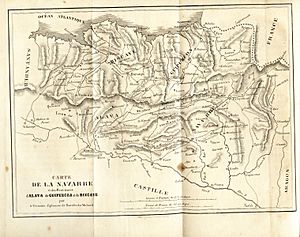

The regions of Aragon, Valencia, and Catalonia had lost their special rights in the 1700s. In the Basque Country, the special status of Navarre, Álava, Biscay, and Gipuzkoa was also challenged in 1833. People in these areas were upset about Madrid's increasing control and the loss of their local freedoms.

Basque Reasons for the Carlist Uprising

The Spanish Liberal government wanted to remove the special laws, called fueros, that the Basque people had. They also wanted to move the customs borders to the Pyrenees mountains. For a long time, a new group of powerful people wanted to reduce the influence of the Basque nobility and their global trade connections.

King Ferdinand VII found strong support in the Basque Country. The 1812 Constitution of Cádiz had taken away Basque self-rule. It said Spain was one unified nation and didn't recognize the Basque nation. So, the Basques supported Ferdinand VII as long as he respected their traditional laws and institutions.

Many foreign observers who witnessed the war supported the Carlists. They saw the Carlists as fighting for Basque self-rule. However, one diplomat, John Francis Bacon, who was in Bilbao, disagreed. He praised Basque governance but thought the Carlists were "savages." He believed Carlos V would remove the Basque freedoms if he became king.

John F. Bacon also wrote that the Basques living north of the Ebro river were free citizens. He compared them to the Spanish, whom he saw as easily controlled by their rulers. Other writers also highlighted the excellent self-rule and republican nature of the Basques. They noted that the Basques did not see themselves as Spaniards.

Basque liberals had mixed feelings. They valued trade with other Basque areas and France. They also wanted unrestricted overseas trade. However, their trade had suffered greatly due to wars and changes in government. By 1826, Spain's large fleet, which included many Basque sailors, was gone. This benefited the British Empire.

Despite their support for self-rule, the Basques felt pressured by Spanish customs duties on the Ebro river. These duties made trade difficult. Many Basque liberals wanted to move these customs duties to the Pyrenees. This would encourage trade within Spain.

When Ferdinand VII died in 1833, Isabella II became queen, with Maria Christina as regent. In November, Madrid's new government changed Spain's administration. They made it uniform across all provinces, ignoring Basque institutions. This caused anger and disbelief in the Basque regions.

Who Fought in the War

People in the western Basque provinces and Navarre supported Carlos. They believed Carlos would protect their traditional institutions and laws. Some historians say the Carlist cause in the Basque Country was about protecting the fueros. Others, like Stanley G. Payne, disagree. Many Carlists believed that a traditional ruler would better respect their old regional laws. Navarre and the Basque provinces had their customs borders on the Ebro river.

Another big reason for the strong Carlist support in the Basque provinces and Navarre was the influence of the Basque clergy. Priests spoke to people in their own language, Basque. This was unlike schools and government, where Spanish was used. The Basque clergy, nobility, and lower classes strongly supported the region specific laws. They opposed new liberal ideas.

On the other side, the Liberals and moderates joined together to defend the new system. This system was represented by Maria Christina and her young daughter, Isabella. The Liberals controlled the government, most of the army, and the cities. The Carlist movement was stronger in rural areas.

The Liberals had important support from the United Kingdom, France, and Portugal. These countries gave money to Maria Christina's government. They also sent military help. This included the British Legion, the French Foreign Legion, and a Portuguese army division. At first, the Liberals were strong enough to win the war quickly. However, an inefficient government and the spread-out Carlist forces gave Carlos time to build up his army. This allowed the war to last for almost seven years.

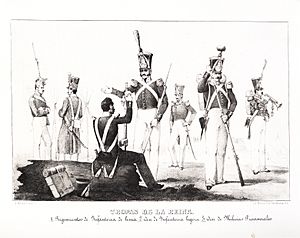

Soldiers and Fighters

Both sides created special troops during the war. The Liberal side formed volunteer Basque units called the Chapelgorris. The Carlist general Tomás de Zumalacárregui created special units called aduaneros. He also formed the Guías de Navarra from Liberal prisoners. These prisoners were given a choice: join the Carlists or be executed.

The term Requetés was first used for the Third Battalion of Navarre. Later, it was used for all Carlist fighters.

The war also attracted adventurers from other countries. For example, C. F. Henningsen from Britain served as Zumalacárregui's bodyguard. Martín Zurbano, a smuggler, also raised a group of men to fight for the queen. His group included smugglers, robbers, and outcasts.

About 250 foreign volunteers fought for the Carlists. Most were French monarchists. Others came from Portugal, Britain, Belgium, Piedmont-Sardinia, and German states.

Many Liberal generals, like Vicente Genaro de Quesada, had fought in earlier wars. Some were veterans of the Peninsular War or wars in South America.

Both sides executed prisoners of war. A terrible event happened at Heredia, where 118 Liberal prisoners were executed by order of Zumalacárregui. The British tried to help. They arranged the Lord Eliot Convention in April 1835. This agreement aimed to treat prisoners according to normal war rules. However, these rules were not always followed.

The War's Progress

Fighting in the North

The war was long and difficult. The Carlist forces, sometimes called "the Basque army," won important victories in the north. This was thanks to their brilliant general, Tomás de Zumalacárregui. He promised to uphold the local laws in Navarre. He was then made commander-in-chief of Navarre. The Basque regional governments also pledged to obey him. Zumalacárregui made his headquarters in the Amescoas area, near Estella-Lizarra. He made his forces strong there and avoided the Spanish forces loyal to Maria Christina. About 3,000 volunteers joined his army.

In the summer of 1834, Liberal forces burned down the Sanctuary of Arantzazu. Zumalacárregui showed his tough side by executing volunteers who refused to advance. The Carlist cavalry defeated a Liberal army sent from Madrid in Viana in September 1834. Zumalacárregui's forces also won a victory over General Manuel O'Doyle in Álava. The Liberal general Espoz y Mina tried to separate the Carlist forces, but Zumalacárregui's army held them back.

By May 1835, most of Gipuzkoa and Biscay were controlled by the Carlists. Carlos V decided to attack Bilbao. This city was defended by the Royal Navy and the British Auxiliary Legion. Carlos believed that if he captured Bilbao, he would get money from European banks to win the war.

During the siege of Bilbao, Zumalacárregui was wounded in the leg. The wound was not serious, but it did not heal well. General Zumalacárregui died on June 25, 1835. Many historians think his death was suspicious. They note that he had many enemies in the Carlist court.

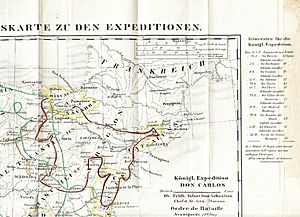

In Europe, most major powers supported the Liberal army. Meanwhile, in the east, Carlist general Ramón Cabrera was fighting well. However, his forces were too small to win a decisive victory. In 1837, the Carlists made a big push called the Royal Expedition. They reached the walls of Madrid but then retreated after the Battle of Aranzueque.

Fighting in the South

In the south, the Carlist general Miguel Gómez Damas tried to create a strong Carlist position. He left Ronda in November 1836 and entered Algeciras a few days later. But after leaving Algeciras, he was defeated by Ramón María Narváez y Campos at the Battle of Majaceite. An English writer said that Narváez saved Andalucía from the Carlist invasion with a brilliant and fast attack.

At Arcos de la Frontera, the Liberal Diego de Leon held back a Carlist group with his cavalry until more Liberal soldiers arrived.

Ramon Cabrera also worked with Gómez Damas in the expedition to Andalusia. After defeating the Liberals, he occupied Córdoba and Extremadura. He was forced out after his defeat at Villarrobledo in 1836.

The War Ends

After Zumalacárregui's death in 1835, the Liberals slowly gained control. However, they could not win the war in the Basque regions until 1839. They failed to capture the Carlist fortress of Morella and lost the Battle of Maella in 1838.

The war had a huge impact on the Basque economy and finances. People suffered from losses, poverty, and disease. They were also tired of Carlos's desire for absolute power and his disregard for their local self-government. In 1838, Jose Antonio Muñagorri negotiated a peace treaty in Madrid called "Peace and Fueros." This led to the Embrace of Bergara.

The war in the Basque Country ended with the Convenio de Bergara (also known as the Abrazo de Bergara). This agreement was signed on August 31, 1839, between the Liberal general Baldomero Espartero and the Carlist General Rafael Maroto.

In the east, General Cabrera continued fighting. But when Espartero captured Morella and Cabrera in Catalonia in May 1840, the Carlists' defeat was certain. Espartero moved to Berga, and by mid-July 1840, the Carlist troops had to flee to France. Cabrera was seen as a hero and returned to Portugal in 1848 for the Second Carlist War.

What Happened After the War

The Embrace of Bergara in August 1839 ended the war in the Basque regions. The Basques were able to keep a smaller version of their local self-rule. This included their own taxation and military draft. In return, they officially became part of Spain in October 1839. Spain was now a centralized country, divided into provinces.

The agreement was confirmed in Navarre. However, things changed in Madrid when General Baldomero Espartero became prime minister and regent in 1840. The government's money was low after the war, and the army needed to be paid.

In 1841, a separate agreement was signed by officials in Navarre. This agreement, called the Ley Paccionada, further reduced Navarre's self-government. It officially made the Kingdom of Navarre a province of Spain in August 1841.

In September 1841, Espartero's government took military control of the Basque Country. They then officially removed Basque self-rule. This moved the customs borders from the Ebro river to the Pyrenees and the coast. The region suffered from famine, and many people emigrated to America.

Espartero's rule ended in 1844. A new agreement was made for the Basque Provinces.

Key Battles of the War

- Battle of Mayals (April 10, 1834) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Alsasua (April 22, 1834) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Gulina (June 18, 1834) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Alegría de Álava (October 27, 1834) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Venta de Echávarri (October 28, 1834) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Mendaza (December 12, 1834) - Liberal victory

- First Battle of Arquijas (December 15, 1834) - Liberal victory

- Second Battle of Arquijas (February 5, 1835) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Artaza (April 22, 1835) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Mendigorría (July 16, 1835) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Arlabán (January 16–18, 1836) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Terapegui (April 26, 1836) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Villarrobledo (September 20, 1836) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Majaceite (November 23, 1836) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Luchana (December 24, 1836) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Oriamendi (March 16, 1837) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Huesca (May 24, 1837) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Villar de los Navarros (August 24, 1837) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Andoain (September 14, 1837) - Carlist victory - This battle ended the British Auxiliary Legion as a strong fighting force.

- Battle of Aranzueque (September 19, 1837) - Liberal victory, ending the Carlist campaign known as the Expedición Real.

- Battle of Maella (October 1, 1838) - Carlist victory

- Battle of Peñacerrada (June 20–22, 1838) - Liberal victory

- Battle of Ramales (May 13, 1839) - Liberal victory

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Primera guerra carlista para niños

In Spanish: Primera guerra carlista para niños