Requeté facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Requetés |

|

|---|---|

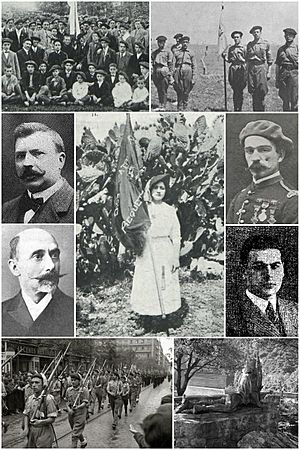

clockwise from top left: Olot, late Restoration; Andalusia, Second Republic; Pérez Nájera; Zamanillo; monument to Requeté, Montserrat; Donostia, Spanish Civil War; Llorens; Roma. Centre: standard-bearer

|

|

| Active | 1900s-1970s |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Traditionalist Communion |

| Type | Militia |

| Engagements | Spanish Civil War |

The Requeté was a group linked to the Carlism political movement in Spain. It started in the early 1900s and lasted until the 1970s. At different times, it acted like a youth club, a street fighting group, or a military-style militia.

The Requeté changed a lot over the years. Here are some of its main phases:

- Early 1900s to mid-1910s: A mixed youth group.

- Mid-1910s to early 1920s: Urban street fighting squads.

- Early 1920s to early 1930s: A quiet period with no clear direction.

- 1931–1936: A military-style group for the Carlist party.

- 1936–1939: Important fighting units during the Spanish Civil War.

- 1940s–1950s: A party branch for youth and former soldiers.

- 1960s: An internal group for loyal members.

The Requeté played a big part in the early months of the Spanish Civil War. Their units were very important for the Nationalist side in some key battles. It is not known if any Requeté groups are active today.

Contents

- How the Requeté Started

- The Name "Requeté" Appears (1907)

- Early Activities (1907–1913)

- Main Activities in the 1910s

- Changes in the 1910s

- After the Reform (1913–1920)

- A Quiet Period (1920–1930)

- Reforming the Requeté (1930–1931)

- The New Requeté (1931–1936)

- The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939)

- After the War (1940s)

- Mid-Francoism (1950s)

- Late Francoism (1960s)

- Decline (1970s)

- Recent Times (1980s and Beyond)

- Images for kids

- See also

How the Requeté Started

Before the 1900s, there were no youth groups in Spain, except for school clubs. In the early 1900s, different political groups started their own youth branches. For example, a socialist youth group appeared in Bilbao in 1903. In 1904, Basque nationalists and radical republicans also formed youth groups. Even non-political groups like the Boy Scouts started around 1911.

The first youth groups linked to the Carlism movement appeared in the early 1900s. Groups called "Batallones de la Juventud" marched in Madrid (1902) and Barcelona (1903). They wanted to show the strength of Traditionalism and maybe scare their political rivals. Some historians think these groups continued an old Carlist tradition of direct action. They believe that small fights in 1900 led to "armed squads of Carlists" who fought in city streets. These groups were stopped by the police, but they showed a new kind of Carlist activity in cities, focused on street violence.

It's not clear if the new Carlist youth group, Juventud Carlista, was meant to control this violence or make it more organized. Its first branch started in Madrid, and by 1903, it was very active in Barcelona. Catalonia, especially Barcelona, had many Carlist youth members. This region was changing fast, from rural to industrial, which helped new urban groups grow. These loosely organized Juventud groups practiced military drills. They also got into more street fights with left-wing groups, especially the Radicals and Anarchists.

The Name "Requeté" Appears (1907)

The exact start of the Requeté organization is not fully clear. In the early 1900s, some Carlist groups in Catalonia used the name "requeté." This name came from a brave battalion from Navarre in the First Carlist War. General Zumalacarregui praised them for their courage. Some writers for Traditionalist newspapers also used "Requeté" as a pen name.

It seems the first efforts to create a Carlist youth group happened in Manresa. In 1907, a local newspaper called Lo Mestre Titas was known as the "voice of the school requeté." Today, experts see it as an unofficial newspaper for young Carlists there. Historians often say that the first group named "Requeté" was started in Manresa in 1907 by Juan María Roma, a 37-year-old publisher. The first newspaper mention in 1908 talked about "Requeté Carlí de Manresa" but didn't mention Roma.

The main goal of the group was to "do propaganda," meaning to spread their ideas. They asked "young Carlists of Catalonia" to do the same. Soon, groups in other places like Sabadell and Girona also started their own Requeté branches.

Local Carlist leaders usually weren't involved in starting these Requeté groups. It seems they were linked to or inspired by Juventud Carlista. Members of Juventud were sometimes called "older brothers" to the younger "jovencitos" in Requeté. Requeté was seen as a step before joining Juventud. Sometimes, it was even called "Requeté de la Juventud Carlista."

Most early Requeté groups were in Catalonia or Levante. By 1910, there were groups in Madrid, and by 1911, in Andalusia, Aragón, Galicia, Old Castile, and the Basque Country. By 1912, they were in Navarre and the Canary Islands. However, many local groups in Spain tried to copy the "Requeté" style from Barcelona.

A party document from later said that Requeté was for older children and young teenagers, aged 12–16, who couldn't join Juventudes. Other notes said the age limits were 8–15. Historians describe these early groups as "peaceful and childish," more like the later Pelayos groups of the 1930s than a military group. Newspapers at the time called Requeté members "young ones," "boys," "children," or "lads." Their purpose was vaguely described as "grow, learn, and train to be a soldier of God," growing in peace but also "prepared for war." Early notes suggest a Requeté member had to be a good Christian but didn't have to be a Carlist.

Early Activities (1907–1913)

In 1909, the Carlist leaders in Catalonia asked Juan María Roma to write official rules for the Requeté. It's not known if these rules were ever used. In 1911, some newspapers printed a draft of rules, but it's unlikely they were adopted. It seems that different Requeté groups worked on their own, without a larger network. Until the mid-1910s, there was no main group to coordinate them.

We don't know the exact number of members. Friendly newspapers said there were over 100 members in Barcelona in 1910 and 130 in Lerida. A 1911 meeting in Tarrasa had 200 young people, and in Valls, there were 50 members in 1912. One report, which might not be accurate, claimed 800 Requetés attended a meeting in Valencia.

Even though the draft rules said only boys could join, photos show girls were also present. Some sources mention "requeté de damas blancas" (Requeté of white ladies), and teenage girls even carried flags.

Larger or richer groups had their own flags, often received in big ceremonies. The first such event in Catalonia was in 1910, and in Valencia in 1911. Basic leadership roles started to appear, usually with a president, and sometimes a vice-president, treasurer, secretary, or librarian. Larger local groups created special sections for drama, charity, trips, education, cycling, sports, or politics and religion. We don't know if they had their own buildings; they might have met in private homes, Carlist clubs, or outdoors. By 1911, there were mentions of common clothing, usually red or blue berets. But before 1913, there was no clear mention of a full uniform.

Juan María Roma seemed to be very important in organizing the early Requeté. Another Carlist leader, Dalmacio Iglesias, supposedly wanted to turn Requeté into fighting groups for street battles. In Valencia, a retired artilleryman named Joaquín Llorens was a key figure. Some newspapers in 1910 called the group "requeté d’en Llorens."

Main Activities in the 1910s

One of the main things Requeté members did was propaganda. They sold party newspapers or pamphlets, handed out free papers, and put up posters. They also tore down posters from rival groups. Their propaganda tours sometimes included small music bands or parades.

They also organized cultural events with a Traditionalist message. These included literary evenings, music, choirs, poetry readings, and theatrical shows. Some gatherings were big cultural events. They also focused on education, with some groups organizing lectures. There was even an "Academia del Requeté" at one point.

Requeté members often took part in religious events like outdoor masses, parades, or pilgrimages. They were expected to be good Christians and take holy communion at least once a month. Many Requeté groups also did charity work, helping the poor or sick. Some groups even had special charity sections.

For outdoor activities, they went on many trips that combined tourism, religion, and propaganda. They marched in organized, military-like groups with flags and music to holy places like Montserrat. Some individuals even went on longer journeys. Newspapers often reported on Requeté members doing military drills and shooting practice. They also played sports, especially cycling. Football was less popular, and there was one climbing group. They even had "Copa Requeté" trophies.

From 1909, Republican newspapers reported many incidents of Requeté-related violence. This included insulting other young people, provocative marches, attacking left-wing newspaper offices, or trying to stop trams to make people observe religious holidays. Hostile newspapers worried about a "young and brave army" trained for "murder, robbery, and arson," taught to hate, and "ready to die and to kill." They were sometimes described as "creatures 8 to 10 years old, cigarettes in their mouths and cards in their hands." Progressive writers warned about a "mock comedy of a civil war."

Requeté members were sometimes arrested by police or faced military trials. There were clashes with police and the Guardia Civil, weapons were taken away, and local officials took action against their clubs. The 1911 street battle in Sant Feliú de Llobregat, which killed several people, might have involved some Requeté members. Violence was reported in Catalonia and the Basque Country. Carlist newspapers said Requeté members were protecting churches or keeping Carlist meetings safe.

Changes in the 1910s

In the early 1910s, the Requeté was a mixed group with 10-year-old children and young men. Their activities ranged from cultural events to street violence. Sometimes, these differences caused funny confusion, but there was no clear structure. Some historians think the idea to reform the group came from the new Carlist leader, Don Jaime. He was reportedly impressed by a French group called Camelots du Roi and wanted to create something similar. He discussed this plan with Llorens in 1910.

General ideas for a new Requeté were released in late 1912. The first known plan for this change was from early 1913. That same year, the 59-year-old Llorens was put in charge of the Comisíon de Requetés, one of 10 parts of the main party leadership. This was the first time the Requeté was officially recognized as a party branch.

Llorens wanted to build a group of disciplined, trained young men. They would be organized into units and able to act together, forming a future "army." He wanted to call them "Grupos de Defensa," with Requeté and Juventud acting as training or support groups. They would have different command levels and be supervised by Carlist politicians. A plan by Llorens suggested splitting Requeté into younger and older sections. A basic unit would have 16 men, four units would form a section, and two sections would form a company, all led by officers. The plan also included badges and a grey uniform.

In 1913, a group called Junta Central Tradicionalista Organizadora de los Requetes de Cataluña was formed. Matías Llorens Palau became its president. This group issued guidelines to organize and unite the existing Requeté groups and appointed provincial leaders. A rulebook was likely published. From late 1913, there were reports of old groups being dissolved and new "escuadras" (squads) being created as described in the new manuals. The same year, the first Requeté units appeared in public wearing uniforms in the "Llorens style."

We don't know the exact results of Llorens's reform. The "Grupos de Defensa" never appeared, and Requeté and Juventud continued to operate separately. The Junta Central Organizadora didn't last long, disappearing after 1914. Instead, the Comisión de Requetés was active until 1919. It's unclear how much local Requeté groups actually changed into structured, disciplined units focused on military-like activities. Some experts think the reform largely failed.

After the Reform (1913–1920)

Llorens's reform happened when Requeté activity was at its peak during the Restoration era. In the late 1910s, it started to decline. It seems that Requeté became more of a military-style group during this time. Reports of violence became more common than news about cultural or charity activities.

Carlist youth were involved in street fights with other groups, especially the "Jóvenes Bárbaros" of the Radicals. There were also clashes with Catalanist and Basque nationalist youth. Many of these incidents involved guns and caused injuries, even deaths. From 1915, there were reports of cars being used in shooting incidents. It's hard to say who started the violence, as all groups acted provocatively. However, it's clear that in many cases, Requeté youth attacked rival offices or tried to break up opposition meetings. There were also more reports of Requeté groups trying to stop elections, for example, by destroying ballot boxes.

Before World War I, Requeté activity became very pro-German and anti-French. When the French president visited Madrid, he saw "Long live Spain and Germany!" paintings signed by Requeté in Catalonia. During the war, Requeté members protected meetings that supported neutrality (which often meant pro-German) or openly supported Germany and Austria-Hungary. In Barcelona, they attacked people who made fun of the German Kaiser. In 1917, some politicians even suggested Germany was funding the group, but there was no proof.

There are signs that Requeté members often wore uniforms. However, police and the Guardia Civil saw military-style clothing as a threat to public order. Organized groups of teenage boys were only allowed to march if they were unarmed and in plain clothes. Some information suggests that military ranks and a clear command structure were introduced. There were also unconfirmed reports of members being expelled from the group.

The relationship with the official Carlist party leaders is unclear. Sometimes, militant youth praised regional leaders. But Carlist politicians also expressed concern and even suggested breaking up some Requeté groups. In the late 1910s, no major party leaders seemed closely involved with the organization. Llorens stopped being active, especially after he disagreed with the Carlist leader about supporting Germany. In 1920, Don Jaime appointed Juan Pérez Nájera, a 75-year-old military man, as the head of all Requeté groups in Spain.

A Quiet Period (1920–1930)

From the mid-1910s, Requeté activity steadily declined. By the early 1920s, the group became very quiet. Experts call this period "disengagement and paralysis" or "irreversible decline." It's not clear why this happened. It could be due to Llorens's unfinished reform, the Carlist party's crisis in 1919, the new leadership's lack of effectiveness, or the restrictions on public activity during the Primo de Rivera dictatorship (1923–1930). It's also possible that Carlism itself was declining in Catalonia, being overtaken by republican, Catalanist, or Anarchist groups.

In the early 1920s, it seemed that Carlist urban activism shifted from youth groups like Requeté to labor unions. Many working-class members of Carlist-linked unions, called Sindicatos Libres, who fought violently with rival unions, were former Requetés. However, the Sindicatos Libres didn't grow much. In 1922, Don Jaime asked the Carlist political leader to revive Requeté and Juventudes into "action groups," but nothing much came of it.

The dictatorship of Primo de Rivera stopped street violence and brought calm. After that, there were no reports of Requeté-related disturbances. If mentioned in the news, they were usually for pilgrimages, issuing newsletters, or taking part in religious services. In some areas, Requeté activity stopped completely. A Barcelona branch even declared itself dissolved and changed its name to "Los Mosqueteros de Jaime III."

Their relationship with the dictator's militia, Somatén, was complicated. In the early 1920s, the two groups used to fight each other. Later, some individuals were members of both. From the mid-1920s, many Requeté members joined Somatén, especially since it was officially recommended by the Carlist leader. In 1927–1928, the government suspected Requeté of planning a coup and arrested some members, like the Barcelona Requeté president. Some Carlist hotheads in Catalonia did plot against Primo, but the party leadership quickly stopped them.

Reforming the Requeté (1930–1931)

When the Primo de Rivera government fell in 1930, the Carlists were relieved that the "long six years of silence imposed by a Dictatorship" were over. Experts say the entire movement was at its weakest point. We don't know the exact state of the Requeté at this time. The available information suggests the group was struggling, with only a few isolated and inactive branches. They mostly focused on restarting party propaganda and religious activities. There were attempts to return to old activities like excursions and sports. Most news about Requeté, though scarce, came from Catalonia or Levante. The leader of the party lived in Levante, so that region was somewhat more active.

In May 1930, Don Jaime called the Carlist leaders to Paris and formed a "Comité de Acción" (Action Committee). Historians believe that as Spain became more unstable, Don Jaime planned for future violent events. Some say that "revitalizing shock groups was a key concern" for him. However, nothing immediately happened. A study on Catalan Carlism in the early 1930s doesn't mention any attempts to revive Requeté groups there. The only sign of focus on the organization was the Cruz de la Legitimidad Proscrita, a high Carlist honor given to a local leader. When the monarchy fell and the Republic was declared in April 1931, Requeté remained quiet and without a clear purpose. In the summer of 1931, Carlist leaders talked with other monarchists and army generals about a coup against the Republic. But they realized they didn't have enough resources for such a plan.

In late summer of 1931, the Comité decided to expand and reform the Requeté. Some experts say it was to "start a possible uprising" and become a volunteer army that could take control of land, like in the 19th century. However, others believe the group was meant to be "mainly defensive." Any remaining features for children were removed, and the group was now for strong, young adult men.

Its main focus moved from Catalonia and Levante to the Basque-Navarrese area. This meant relying more on members from rural areas and small towns, rather than big cities like Barcelona. Requeté was to become a group that was both military-like and a militia. Its members would be disciplined, organized, and trained in combat and using firearms. Professional army officers would oversee these changes. The decisions made in late 1931 set a completely new path. Soon, Requeté would become a totally new group, very different from its early days as a children's group or its later role as urban street fighters.

The New Requeté (1931–1936)

The Requeté's history during the Republic had three main phases. The first phase began with Colonel Eugenio Sanz de Lerín, who became the Requeté's chief instructor in 1931. In a few months, he built a network of 2,000 men in Navarre. They were organized into new 10-man units called decurias. Their first goal was to protect religious buildings. With help from local priests, the group tripled in size by the end of the year.

However, in early 1932, Requeté faced problems. The Comité de Acción was shut down, key instructors were arrested, and some groups were banned. Most decurias were "practically dismantled." Outside of Navarre, Requeté was limited to harmless groups in big cities. Before a military plot in August 1932, Sanz de Lerín claimed he could provide 6,000 Requetés, but experts say this was not true. Outside Navarre, there was hardly any growth, and even in Catalonia, Requeté was a disappointment.

The second phase started when retired army colonel Enrique Varela was appointed National Chief of Requeté in late 1932. He changed the decuria system to a military-like structure, up to the battalion level. He also issued many rulebooks. Most importantly, in 1933–1934, he traveled the country, making appointments, giving orders, overseeing growth, and personally providing training. Even though some regions like Catalonia resisted these efforts, the organization gained strength outside Navarre too.

In early 1934, the party leadership formed the Frente Nacional de Boinas Rojas (National Front of Red Berets). This was an attempt to create a national Requeté structure, separate from local Carlist groups. José-Luis Zamanillo was appointed its political leader. About 150 members received military training in Fascist Italy. In late 1934, Requetés offered their help to military commanders fighting the October revolution for the first time. By early 1935, Requeté had a truly military character that it lacked before. Its strength was 20,000 men.

The third phase began in mid-1935 when Varela handed over his role to Ricardo Rada. At this time, getting weapons was the main concern. Small arms were smuggled from France or bought inside Spain. In early 1935, the group owned 450 machine guns. Plans for military action were already being made, though they were meant for defense against revolution rather than an uprising. By late 1935, Requeté sections were no longer just additions to Carlist clubs. They became the most active part of the Carlist movement. It seemed that everything else was just a support for Requeté.

In December 1935, Requeté was on alert for the first time, waiting for an order to rise up. Another plan, this time for a Carlist-only uprising, was developed but then abandoned in April–May 1936. In late spring of 1936, Requeté had 10,000 fully armed and trained men, plus 20,000 in a support group. Unlike other parties' action groups, which were "mainly used for street fighting," Requeté was a "true citizen army." It could carry out small military operations.

The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939)

The early part of the Spanish Civil War was the only time Requeté had a big impact on Spanish history. In three out of four regions where Carlists were strongest—Catalonia, Levante, and the Basque Country—the military coup failed. Requeté rebels were captured, went into hiding, or fled to the Nationalist zone.

However, in Navarre, the organization was strong enough to take control of the region almost by itself. It also helped quickly capture Western Aragón. In late summer of 1936, Requeté was crucial for the Nationalist takeover of Gipuzkoa. Smaller Requeté groups also played a role in capturing Western Andalusia. Units from Navarre, Old Castile, Leon, and Galicia tried to cross Sierra de Guadarrama to reach Madrid, but they failed.

In the first weeks of the war, Requeté volunteers made up about 15–20% of all Nationalist troops in Spain. They were vital for some early strategic successes. For example, they cut off the Northern enclave from France and created a barrier between the Republican-held Basque Country and Aragon.

Over time, Requeté became a smaller part of the rebel troops. Even though the organization kept 20,000–25,000 people in its frontline units, the overall Nationalist army grew. So, the percentage of Requetés dropped to 9% by April 1937, 5% by January 1938, and 3% by the end of the war. They were grouped into Carlist-only infantry battalions called tercios. About 40 of these are known, but many were small and short-lived, later merging into other units. Only about 15 operated for most of the war. They were usually led by professional army officers, who might or might not have been Traditionalist.

The Navarrese tercios were grouped into "Navarrese Brigades." These units also included army groups and other militias. For much of the war, they worked together as an army corps. Other tercios were assigned to various larger, mixed units. Most Requeté tercios fought first in the Basque Country, then Cantabria, Asturias, the Teruel front, Maestrazgo, and finally in Catalonia.

The political unification didn't change Requeté tercios much. Although formally part of the army, they continued to operate as Carlist battalions. Recruitment was voluntary, handled by party political groups in the rear. The exact social makeup of the units is not clear. Existing information suggests they were mostly made up of working-class members, ranging from 55% to 85%.

It's estimated that about 60,000 to 70,000 men served in Requeté at some point, with more than half of them from Navarre. It was common to find brothers, cousins, or father-and-son pairs serving together. There were even a few cases of three generations serving. Because Requetés were often used as shock troops, like the Moroccan Regulares and the Foreign Legion, their losses were higher than the average Nationalist losses. The number of KIA (killed in action) is estimated between 4,000 and 6,000. The total number of casualties (killed, wounded, missing) is between 13,000 and 34,000.

After the War (1940s)

After the war, Requeté battalions were disbanded. However, the organization continued to exist as part of local Carlist groups. Officially, the Traditionalist Communion joined the state party, but the Carlist movement operated unofficially or semi-secretly. No sources confirm a national Requeté leadership, though Zamanillo, who resigned in 1937 due to the unification, later took on the role of National Delegate of Requetés in the early 1940s.

In areas with strong Carlist support, regional leaders included a Requeté delegate. In regions like Navarre and Catalonia, many small Requeté groups operated locally. The national party leadership tried to reorganize the network. In a time of confusion, they wanted to ensure Requeté's loyalty and even make it the party's main support. Some authors refer to a "rebuilt Requeté." New members were recruited, ranks were kept, and in some cases, sub-sections were developed.

The exact role of Requeté is not clear. There is no information on military training. However, various groups thought about using the structures either to recruit for units that would fight alongside the Nazis or as a spy network for the British. It seems that the groups were mostly involved in illegal propaganda activities, like handing out leaflets, graffiti, or selling Carlist goods. However, a Requeté newsletter was officially published, pretending to be from former soldiers.

Uniformed groups attended various gatherings, usually religious events or commemorations of wartime actions. Propaganda activities often led to fights with the Falange or security forces. Even before 1939, most conflicts within the state party were about Requetés refusing to give up their identity and adopt the official national-syndicalism. During the 1940s, Falangists and groups called "requetés" engaged in intimidation, fist-fights, sabotaging rallies, or attacking buildings. Some Carlist groups proudly reported these fights as their main activities. The biggest riots happened in 1945 in Pamplona, where official Requeté groups actively prepared the disturbances. These fights continued with less frequency until the early 1950s.

Police monitored Requeté groups, but there was no systematic effort to stop them. Wearing a badge in public or having a Requeté ID card could lead to arrest. However, small uniformed groups were usually allowed at events for former soldiers or religious gatherings. Sometimes, even Requeté commemorative rallies were banned, or officials who allowed them were warned. An attempt to open a Requeté Museum in Seville was stopped by the government. Requeté members arrested during street fights were usually released after about two weeks in jail, though a few leaders were held much longer after the Pamplona riots.

Around 1949 and 1950, the government allowed public appearances of a Requeté-style group that supported a different Carlist leader favored by the regime. Over time, the official policy towards Carlist organizations became more relaxed, and the government even allowed large rallies.

Mid-Francoism (1950s)

In the early 1950s, Requeté faced a generation gap. Former soldiers from the war were in their 40s, busy with daily life, and talked about their wartime experiences over drinks. Among young activists, the focus shifted from rural areas to big cities. These young activists preferred the party's academic organization, AET. For them, Requeté was more like a glorious relic of the past, suited for wartime but not for political activism.

We don't have membership numbers, but the organization played a small role in the Carlist movement. In the mid-1950s, when the party stopped opposing the government and started working with it, Requeté was not involved in these decisions. Zamanillo, as National Delegate of Requeté, continued to represent the organization in the national leadership, and regional leaders worked locally. But it's unclear how strong the network still was on the ground.

The Carlist movement saw a clear revival in 1957 with the appearance of Don Carlos Hugo and his team. However, this had little effect on Requeté; the focus was more on AET. Uniformed activists were needed for Traditionalist rallies like the Montejurra ascent. In big cities, "requetés" were sometimes arrested, for example, for carrying signs against Don Juan Carlos. However, it's not clear if these individuals were actual Requeté members or just former soldiers and party activists.

There were some signs of an attempted revival. In 1957, Zamanillo appointed Arturo Márquez de Prado y Pareja, 33, as "chief instructor," seemingly to restart military training. Some sub-sections of the organization were also created. In 1958, a "Comisión Técnica Nacional del Requeté" (National Technical Commission of Requeté) was noted for its long political analysis. This report, meant for party leader José María Valiente, recommended a strong and unyielding stance against the Juanistas (supporters of Don Juan Carlos) and the government.

In the late 1950s, Requeté was increasingly seen as an old-fashioned part of the Carlist movement and was pushed aside. While the young supporters of Don Carlos Hugo were happy to let it fade away, others saw a need for reorganization. However, the ideas for reorganization were sometimes contradictory. In 1959, the Navarrese leader complained about constant disagreements within the regional organization about finding a Requeté chief. He suggested appointing a new, strong military leader. On the other hand, some reports argued for the opposite: more independence for Requeté groups.

The central party command's response was unclear. By 1960, the party's national leadership formed seven specialized departments, and the Requeté Commission was one of them. That same year, Zamanillo, who was a close aide to Valiente, was promoted to General Secretary of the Communion. He left his role as Requeté delegate, which he had held for over 25 years. Márquez de Prado replaced him in this role.

Late Francoism (1960s)

Under the new leadership, Requeté focused more on military-style training. Systematic training courses were organized. Márquez de Prado considered helping Cuban counter-revolutionaries and the OAS in Algeria. A police report from 1962 claimed that the structures were "perfectly organized." Carlists close to Don Carlos Hugo were increasingly worried about Requeté's "militarist influence" in the Communion.

At this time, the organization started getting involved in political debates within the party for the first time. Márquez de Prado was suspicious of the prince, his circle, and their new ideas. Requeté gradually became a stronghold of traditional Carlist beliefs. Ramón Massó and other leaders who supported Don Carlos Hugo decided that Márquez de Prado, who was focused on fighting counter-revolution, needed to be removed. As for the organization itself, they were unsure whether they could control it or if it should be pushed aside.

In 1963, Pedro José Zabala, one of Don Carlos Hugo's supporters, presented Valiente with his plan for Requeté's overhaul. This group believed that the organization "should have a more social and political mission" and that Márquez de Prado should be removed. The brother of another supporter of Don Carlos Hugo was suggested as the new national delegate. The same year, Márquez de Prado asked Valiente for the opposite: to strengthen his own powers. Some thought this was a move inspired by Zamanillo, who had already been expelled from the Communion.

At this time, the "gradual dismantling" of Requeté, seemingly planned by Don Carlos Hugo's supporters, was ongoing. This happened even though its uniformed units played ceremonial roles during important Carlist rallies. Still officially represented in the National Board and National Secretariat, Requeté's budget in 1963 was only 4% of the entire Communion's spending. The pressure on Valiente grew, and in early 1965, Márquez de Prado was dismissed. He was replaced as National Delegate of Requeté by Miguel de San Cristobál Ursua, a 56-year-old from Navarre.

San Cristobál's initial direction is unclear. On one hand, he prepared for the decentralization and demilitarization of the organization. On the other hand, some decisions suggested building "action groups," possibly involved in terrorist activity. During the party congress of 1966, this was the future Requeté direction supported by most participants. However, that same year, another option was chosen. Like most other sections, the national Requeté leadership was disbanded, and its local groups were placed under the control of corresponding local boards. This was a return to the pre-1934 pattern.

All of this, plus San Cristobál's speech at Montejurra, caused protests. Some provincial boards accused the secretariat, dominated by Don Carlos Hugo's supporters, of manipulating Carlist structures. Many activists resigned or left. An internal report from 1967 claimed that Requeté's disorganization "is total." Some historians say that in a few years after decentralization, Requeté "practically disappeared." During the 1968 Montejurra event, the first fist-fights were recorded between requetés and members of the newly formed GAC. However, some Traditionalists concluded that Don Carlos Hugo's supporters had already won the battle for Requeté, which then allowed them to control the entire party.

Decline (1970s)

From the late 1960s, the main newspapers of Don Carlos Hugo's group stopped mentioning Requeté. In the early 1970s, San Cristobál was only mentioned in party newspapers as the regional leader in Navarre. Even regional leadership groups did not include a Requeté representative.

The Traditionalist group gave up trying to regain control over the organization. They focused on keeping their influence in the Requeté hermandad (brotherhood) of former soldiers, which had been led by another supporter of Don Carlos Hugo since 1965. With help from state security services, they succeeded, but the entire movement for former soldiers, which was always prone to splitting, soon fell into complete chaos. In 1971, the leader set up a rival organization in France. Various other brotherhoods followed their own political paths, usually focused on late Francoist structures and Don Juan Carlos. In 1972–1973, some of them tried to become centers of a revived, anti-Don Carlos Hugo Carlist movement, but they failed.

In the early 1970s, the Carlist movement, dominated by Don Carlos Hugo's supporters, underwent a complete structural change. The goal was to turn it into a new, mass-based party. During a series of meetings in 1971–1972 in Arbonné, France, the Traditionalist Communion was transformed into a totally new entity, the Partido Carlista. Its structure did not include any Requeté section.

There is no known document or single decision that officially dissolved the entire organization. However, historians say that during the creation of the Partido Carlista in the early 1970s, the Requeté—which was already almost gone—was effectively dissolved along with all other sections of the movement. The role of a violent, military-like arm was taken over by Grupos de Acción Carlista (GAC). This new section purposely broke with the Requeté tradition, as it reminded people of old civil war divisions and reactionary ideas. Some experts believe that in some ways, GAC was both an heir to and a different version of Requeté.

At the time, the Traditionalists tried to build their own Requeté structure. The key person in this process was Márquez de Prado, helped by Zamanillo. At one point, it seemed even San Cristobál might get involved. The exact results of these efforts are not clear. In 1973, a group called the Permanent Commission of the National Board of Requeté Chiefs, led by Márquez de Prado, issued a statement. It declared Don Carlos Hugo a traitor to their cause and promised to rebuild a true Carlist organization. It's not clear if there was any real structure behind this or if the signers only represented themselves.

Initially, the group seemed to lean towards Don Juan Carlos as a royal leader, though they also had some "mental reservations." Eventually, in 1975, Márquez de Prado and his followers pledged loyalty to Don Sixto. His group, called the National Leadership of Requetés, continued to issue statements in 1976. It might have been involved in the Montejurra shooting that same year. In 1977, Márquez de Prado was named National Chief of Requetés by the emerging Traditionalist Communion. However, there is hardly any sign of an organized Requeté network existing in the late 1970s. The ETA campaign of assassinations against Carlists did not lead to the creation of any revenge groups.

Recent Times (1980s and Beyond)

In the 1980s, all Carlist groups went through a period of confusion and big changes. However, none of the many organizations or groups claiming to represent the Carlist or Traditionalist line kept a section that was a direct or indirect continuation of Requeté. GAC, which was never officially supported by the Carlist Party, stopped operating. The Asociación Juvenil Tradicionalista (Traditionalist Youth Association), a weak and shadowy group linked to Don Sixto that appeared in the late 1970s, also disappeared. Its members sometimes appeared at right-wing events in khaki uniforms and red berets.

The name "requeté" was most often used in connection with various organizations of former soldiers from the civil war tercios. Due to changing political views and a shift against Franco, their activities became less public and more private, small-group meetings, even in Navarre. Some continued as legal owners of monuments built during Franco's time and published books on the history of their units. However, frequent death notices in newspapers, mentioning recently deceased "requeté until his death" or "volunteer requeté of the Crusade," showed that the number of former fighters was getting smaller. These death notices are still published today, though now they usually refer to "the last living combatant" from a specific region or battalion.

The arrival of the digital age and social media has led to a return of individuals or groups calling themselves "Requeté." A few profiles on platforms like Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube show some kind of self-proclaimed connection to the Requeté tradition. Some go a bit further and form informal "Friends of Requeté" groups, re-enactment teams, Requeté associations of "women and men defenders of the traditional four-part motto of God, Homeland, Rights, and Legitimate King," or act like a military-style, uniformed "New Requeté" organization. Most of these profiles are either inactive or barely active.

Some continue to publish notes styled as official announcements, signed either by "Commander General of the Requeté" or by "National Leadership of the Requeté," for example, in 2016 or 2020. Individuals who sign these notes use a military tone. They appear to support the Carlist leader Don Carlos Javier. They lecture rival Traditionalist groups on their rights to use Requeté symbols or uniforms and suggest that the organization is still active. People connected to these profiles appear at Montejurra ascents organized by the Carlist Party, where some participants, including females, wear military-like clothing.

Images for kids

-

clockwise from top left: Olot, late Restoration; Andalusia, Second Republic; Pérez Nájera; Zamanillo; monument to Requeté, Montserrat; Donostia, Spanish Civil War; Llorens; Roma. Centre: standard-bearer

-

early scouting, Spain

-

Manresa requeté

-

abanderadas, Barcelona

-

Junta de requeté, Barcelona

-

Tarragona requeté

-

Olot requeté

-

abanderada, Pamplona

-

Sant Feliu requeté

-

Valls requeté

-

Madrid requeté, 1933

-

drill of Andalusian requeté, 1934

-

on parade, Civil War

-

unidentified uniformed unit with Carlist flags, Donostia 1942

-

stone erected by ex-combatant requeté organisation, Catalonia

-

repeatedly vandalized stones with names of fallen requetés, Navarre

See also

In Spanish: Requeté para niños

In Spanish: Requeté para niños