José Luis Zamanillo González-Camino facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José Luis Zamanillo González-Camino

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

José Luis Zamanillo González-Camino

1903 Santander, Spain

|

| Died | 1980 (aged 76–77) Madrid, Spain

|

| Occupation | Lawyer, politician |

| Known for | Politician |

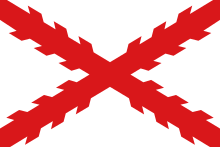

| Political party | CT, FET, UNE |

José Luis Zamanillo González-Camino (1903–1980) was an important Spanish politician. He was a leader of the Traditionalist movement, especially within Carlism. He led the Carlist group called Requeté during the Second Spanish Republic.

Later, he worked with the government during the Franco era, even though he was against it in the 1940s. After Franco's rule, he was part of a group that wanted to keep the old ways as Spain moved towards democracy. He served in the Spanish parliament from 1933 to 1936 and again from 1961 to 1976.

Contents

- Early Life and Family

- Parliament Member and Requeté Leader (1931-1936)

- Planning the Uprising (1936)

- Against Franco's Rule (1937-1954)

- Working with Franco's Government (1955-1962)

- Conflict and Expulsion (1962-1963)

- Working with Franco's Government (1964-1974)

- After Franco's Death (1975-1980)

- See also

Early Life and Family

José Luis Zamanillo's family came from Biscay. His great-grandfather and grandfather were pharmacists. His father, José Zamanillo Monreal (1866-1920), also became a pharmacist in Santander.

His father was also a strong supporter of Integrism, a type of Traditionalism. He helped start Catholic groups and unions in Cantabria. He also helped run a newspaper called El Diario Montañés, which supported his political views. He served as a local council member in Santander.

José Luis's mother was María González-Camino y Velasco. Her family was wealthy and involved in business and politics in the region. José and María had six children. They taught their children to be proud of their Christian and Spanish heritage. José Luis was the second oldest. His older brother Nicolás became a pharmacist, and his younger brother Gregorio became a doctor. His sisters, Matilde and María, were also involved in Traditionalism.

José Luis went to a Jesuit school in Orduña and later studied law. He started his law career in Santander around 1930. In 1931, he married Luisa Urquiza y Castillo (1905-2002). They had 12 children, though two died young. Some of his children also became Traditionalists. His cousin, Marcial Solana González-Camino, was a well-known Traditionalist writer and philosopher.

Parliament Member and Requeté Leader (1931-1936)

In the early 1930s, José Luis and his brothers joined the Comunión Tradicionalista, a united Carlist party. In the 1933 elections, José Luis was elected to the Cortes (the Spanish parliament) for Santander. This was a surprise, as he was a new face among the Carlist leaders.

As a parliament member, he worked to help fishermen in Cantabria. He generally followed the Carlist party's strategy, often disagreeing with the government. However, he became more famous for his work outside parliament.

In 1934, he was chosen to lead the Special Delegation for the Requeté. The Requeté was the Carlist party's own military-style group. José Luis was in charge of organizing, funding, and recruiting for the Requeté. His main goal was to turn the Requeté into a strong national force. He succeeded, growing the group from 4,000 members in 1934 to 25,000 by mid-1936.

Zamanillo was considered a strong Carlist leader. He was against alliances with other monarchist groups. He also had good relations with the local Falange leaders. In the 1936 elections, he lost his seat in parliament. After this, he focused even more on building up the Requeté, traveling around the country to gather support.

Planning the Uprising (1936)

In March 1936, Zamanillo joined a Carlist group that was planning an uprising against the Republic. He helped create a plan for the Carlists to take over the government by themselves. This plan failed in June 1936.

After that, the Carlists started talking with military leaders who were also planning a revolt. Zamanillo met with General Mola in June and July. He used the secret name "Sanjuan" during these talks. He wanted a political agreement before the Carlists fully joined the military's plan.

On July 15, Zamanillo ordered the Requeté to get ready. Two days later, he gave the order for them to join the uprising.

When the Spanish Civil War began, Zamanillo flew from France to the Nationalist zone. In August 1936, he joined the new Carlist wartime leadership. He helped lead the Requeté, focusing on recruitment and organization. He visited the front lines and praised the cooperation between Carlists and Falangists.

After the death of the Carlist king Alfonso Carlos in October, Zamanillo traveled to Vienna for the funeral. He supported Don Javier as the new Carlist leader. He found it hard to accept the idea of a military dictatorship, even a temporary one, before a Traditionalist monarchy could be restored.

In late 1936, Zamanillo continued to organize the Requeté. He strongly believed that Carlist units should remain independent. He also worked on a plan to train Carlist officers.

In December 1936, he was with the Carlist leader Manuel Fal Conde when General Dávila gave Fal Conde a harsh choice: leave Spain or face serious trouble. Zamanillo's exact reaction is not clear, but he returned to Toledo with Fal Conde.

Against Franco's Rule (1937-1954)

After Fal Conde left Spain, Zamanillo became a strong supporter of his views within the Carlist command. He tried to get Fal Conde to return, but it was difficult as rumors spread about combining Carlism into a new state party under Franco.

In February 1937, Zamanillo attended a meeting in Portugal that confirmed him as a member of the Carlist executive. In March, he and Valiente were very skeptical about uniting with other groups. They insisted that attacks on the Carlist leadership were unacceptable.

After the Unification Decree in April 1937, which forced political groups to merge, Zamanillo was very angry. He resigned from all his positions. He was so upset that he believed Fal Conde's exile was better because it allowed him to keep his honor.

Some sources say Zamanillo joined Requeté combat units, but details are scarce. He continued to work against the unification. In November 1937, he helped Carlist volunteers who left Falange-controlled units and sent them to new Carlist groups.

After the Nationalists took over Cantabria, some young local Carlists formed groups to resist the unification. These groups were sometimes called "Tercio José Luis Zamanillo" and were later prosecuted. It's not clear how much Zamanillo was involved.

In early 1939, just before the war ended, Zamanillo signed a document called Manifestacion de los Ideales Tradicionalistas. This document, sent to Franco, argued that it was time to bring back the Traditionalist monarchy. Franco did not respond.

In the early 1940s, Zamanillo was a key figure in keeping Carlist beliefs pure. He made sure the Carlists stayed neutral during World War II. He also rejected the claims of the new Alfonsist leader, Don Juan, and opposed working with Franco's government. In 1941, he called Franco's rule a "totalitarian system" that people rejected.

Zamanillo traveled around Spain, giving speeches at meetings. In 1943, he signed another Carlist document asking for a Traditionalist monarchy. In May, he was arrested and exiled to Albacete until April 1944. He tried to keep the Requeté groups from falling apart. In 1945, he was involved in riots in Pamplona. He was arrested and sentenced to prison in 1946.

By May 1946, Zamanillo was free again. He regularly attended the Carlist gathering at Montserrat. In the late 1940s, his relationship with Sivatte, a leader of Catalan Carlism, became difficult. Zamanillo wanted strict discipline, which often went against Sivatte's ideas.

He was confirmed as a member of the Carlist National Council. He wanted to protect the Traditionalist identity from Franco's influence and suggested creating a center for studying their beliefs. In 1948, after a trip to Rome, a communist newspaper even noted him as a Carlist leader whose disagreement showed Franco's government was weakening.

It's not clear where Zamanillo lived or how he earned a living in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He was sometimes mentioned in connection with Santander or Madrid, often related to education. He likely continued working as a lawyer. In 1953, he was involved in a legal case related to the children of another Carlist leader. This might show that his relations with Franco's government were improving.

On the Carlist side, he remained loyal to Fal Conde and continued to fight against the Sivattistas. It's not clear if he supported asking Don Javier to become the king in 1952, but he later said it was a big mistake. In 1954, he was confirmed as a member of the Carlist National Board.

Working with Franco's Government (1955-1962)

When Fal Conde resigned in August 1955, Zamanillo was still a powerful figure in the Carlist party. Don Javier did not name a new main leader but created a new group called Secretaría Nacional. Zamanillo became a part of this group.

At this time, some Carlists wanted to be very strict against Franco, while others wanted to be more flexible. Zamanillo, who had been a strong opponent of Franco for years, surprisingly became a supporter of working with the government. This was a strategy led by Valiente.

Many Carlists were strongly anti-Franco. At the 1956 Montejurra gathering, some tried to stop Zamanillo from speaking. But Zamanillo and those who wanted to work with the government gained power. Don Javier, the Carlist leader, supported Zamanillo. Zamanillo became the link to the Movimiento, which was Franco's official political movement. This was a difficult job because many Carlists disliked the Movimiento. Zamanillo, Valiente, and Saenz-Díez became the three main leaders of the party.

This new strategy seemed to work. In 1957, there were rumors that Zamanillo might get a high position in Franco's government. He continued to argue that working with the government was the best way to fight against the Juanistas, another royalist group.

In 1958, he was made secretary general, a new high-level position under Valiente. He also became the regional leader for Castilla la Vieja. He supported the introduction of the Carlist prince Carlos Hugo to Spain. Zamanillo used his connections with government officials to help Carlos Hugo, for example, by getting him a residence permit in Madrid and helping the Bourbon-Parmas get Spanish citizenship.

Around 1960, Zamanillo's influence in Carlism was at its peak. Even though Valiente was the official leader, Zamanillo had more respect because of his Requeté past. He continued to lead the Requeté until 1960. He was also in charge of disciplinary actions within the party.

He organized "marches to the Valle de los Caídos" (Valley of the Fallen), which allowed Carlists to meet with Falangists. He often met with Movimiento officials, even though he was unsure of their true intentions. In 1961, Zamanillo was appointed to the Consejo Nacional, which gave him a guaranteed seat in the Cortes. In 1962, he was even received by Franco himself.

Conflict and Expulsion (1962-1963)

Zamanillo's efforts to help Carlos Hugo enter Spain were successful, and the young prince moved to Madrid in January 1962. Carlos Hugo and his young team started new initiatives. Zamanillo saw these as part of the strategy to work with the government and supported them. He even spoke about how Carlist beliefs could evolve.

However, Carlos Hugo and his aides, like Ramón Massó and José María Zavala, did not feel the same way about Zamanillo. They saw him as an old-fashioned leader, brave but not very good at politics, and too inactive. As Carlos Hugo's group gained more power, their relationship with Zamanillo became difficult. It started as a generational conflict, made worse by Zamanillo's strong belief in his own authority. He became worried about Carlos Hugo's "inner circle," while the younger group was skeptical of Zamanillo's "Requeté group" wanting too much power.

Within weeks, suspicion turned into a big conflict. Zamanillo began to doubt if Carlos Hugo's followers truly believed in Traditionalist ideas. They, in turn, saw Zamanillo as the main obstacle to their power and decided to remove him. They were confident in the prince's support and pushed Zamanillo to resign from his position. Zamanillo meant this as a protest, not a final resignation.

While his resignation was being considered, in the spring of 1962, he opposed the changes Carlos Hugo's group proposed. He spoke out against "delfinismo," which meant putting "sons against fathers." At the same time, he started the Hermandad de Antiguos Combatientes de Tercios de Requeté, an organization for former Requeté fighters, hoping it would help in the coming power struggle. He openly challenged Carlos Hugo's new ideas.

The conflict grew over several issues. In September 1962, to Zamanillo's shock, his resignation was accepted, even against Valiente's advice.

From late 1962, Zamanillo strongly opposed Carlos Hugo's group. He wrote a letter criticizing Carlos Hugo as ignorant and revolutionary. In 1963, Massó and his team worked to sideline Zamanillo's supporters. They spread rumors about his disloyalty and gathered support from other important figures. Zamanillo played into their hands by resigning from other roles, including in the Hermandad.

The conflict reached its peak in June 1963, when Carlos Hugo's group attacked Zamanillo with many accusations at a party meeting. In November, the leadership asked for Zamanillo to be expelled. Don Javier agreed, and Zamanillo was removed from the party by the end of the year. Carlos Hugo's strategy worked perfectly: they hid their modern agenda, isolated Zamanillo, provoked him, and removed the key person who was trying to stop them from taking control of Carlism.

Working with Franco's Government (1964-1974)

In the early 1960s, Zamanillo was seen as a symbol of working with Franco's government. This was clear when he was appointed to the Consejo Nacional in 1961. In 1962, Franco considered him for a high government position, but this was stopped by Carrero Blanco, who mistakenly thought Zamanillo supported Carlos Hugo.

After being expelled from Carlism, Zamanillo was welcomed by the hardliners in Franco's Movimiento. In 1964, he received a high honor, the Gran Cruz del Mérito Civil, showing his good relationship with the government. His position in the Consejo Nacional was renewed several times, which meant he kept his seat in the Cortes.

Within Franco's government, Zamanillo held important, though not top, positions. In 1964, he became secretary of a commission that worked on new ideas for Falangism. In the Cortes, he helped draft a law about the Movimiento, which was later dropped. In 1967, he became one of the four secretaries of the parliament, a role he held again in 1971. He also represented Spain in international parliamentary groups. In 1970, he received another military honor. His highest official position came in 1972 when he joined the Consejo de Estado, a top advisory body.

However, Zamanillo had less influence on real political decisions. He sided with the Falangist core, which lost power to the technocrats (experts in government) during the 1960s. Even though he spoke with Franco "many times" and believed he was right, he couldn't convince Franco to stop political changes he opposed, like new labor laws or press laws. He especially disliked the 1967 Law on Religious Liberties.

On the other hand, he supported the introduction of the Tercio Familiar in 1966, seeing it as a step towards a Traditionalist type of representation. He believed that Traditionalism was more about its core beliefs than about who was king. In 1969, he voted for Juan Carlos to be the future king. In late 1973, Zamanillo was part of one of the last attempts by hardliners to gain control, but this group was soon dissolved.

Even though Don Javier called him a "false Carlist," Zamanillo still saw himself as a Carlist. He continued to lead the Hermandad of ex-combatants, sometimes removing those who strongly supported Don Javier. Around 1970, he thought about using this group to start a new Carlist organization, a "Comunión without a king." This organization became the existing Hermandad de Maestrazgo. Zamanillo led its national board in 1972 and joined its leadership in 1973. With Valiente and Ramón Forcadell, he emphasized that Falangists and Traditionalists should work together for Spain and Franco. However, this organization did not gain much popular support and did not become a true Carlist alternative to the new Partido Carlista.

After Franco's Death (1975-1980)

In the final years of Franco's rule, Zamanillo worked to create a large Traditionalist organization. After a law in December 1974 allowed political groups, he first tried to gather support through a new magazine called Brújula. This magazine aimed to unite "supporters of the traditional, social, and representative Monarchy."

In June 1975, this effort led to the creation of Unión Nacional Española (UNE), which gathered 25,000 signatures. Zamanillo joined its leadership. In early 1976, he became co-president of UNE with Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora. UNE followed Traditionalist principles. Zamanillo explained that their goal was a "peaceful and political July 18th" (referring to the start of the Civil War). He played down differences with other right-wing groups and suggested forming a National Front with other parties.

In May 1976, he helped organize a Traditionalist attempt to take control of the annual Carlist Montejurra gathering, which had been controlled by Carlos Hugo's followers since the mid-1960s. This day led to violence, and two members of the Partido Carlista were shot in what became known as the Montejurra massacre.

Still a member of the Cortes, Zamanillo joined Acción Institucional, a group close to the hardline "búnker" (a term for Francoist hardliners).

Before the elections in late 1976, UNE joined the Alianza Popular coalition, and Zamanillo signed its founding document. At the same time, he seemed unsure about UNE and disappointed with Juan Carlos. In February 1977, he helped create a strictly Carlist organization called Comunión Tradicionalista and joined its executive. The leader of this party was Sixto, Carlos Hugo's younger brother, who was also a Traditionalist.

In the June 1977 elections, Zamanillo ran for the senate in Santander on the UNE/AP list but lost badly. UNE became very divided. At its General Assembly in November 1977, Zamanillo and his supporters demanded to leave Alianza Popular. In the chaos, they held a separate meeting and elected a new party leadership. The opposing group appealed in court and won. In December 1977, Zamanillo was expelled from UNE. He then focused on Comunión, which joined the Unión Nacional alliance before the 1979 elections. Zamanillo did not run in these elections.

See also

In Spanish: José Luis Zamanillo para niños

In Spanish: José Luis Zamanillo para niños

- Carlism

- Spanish Civil War

- Carlo-francoism

- Spanish transition to democracy

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |