Movimiento Nacional facts for kids

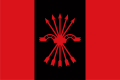

The Movimiento Nacional (which means 'National Movement' in English) was a powerful organization in Spain. It was set up by General Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War in 1937.

During Franco's rule in Spain, this movement was presented as the only way for people to be involved in public life. It followed a system called corporatism. This idea meant that only certain groups, like families, towns, and unions, could speak for the people. The Movimiento Nacional was finally ended in 1977.

Contents

What Was the National Movement?

The Movimiento Nacional was made up of a few key parts. These were the main groups that supported Franco's government:

- The only legal political party: This party was called Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS). It was created at the start of the Spanish Civil War. All other political parties were banned.

- The only trade union: This was called the Spanish Syndical Organization (OSE). People often called it the Sindicato Vertical. It brought together both employers and workers. This was different from other unions that focused on workers' rights against employers.

- Government workers: All people who worked for the government had to promise to follow the rules of the National Movement.

Who Led the Movement?

The National Movement was led by Francisco Franco himself. He was known as the Jefe del Movimiento (Chief of the Movement). He had help from a special minister called the "Minister-Secretary General of the Movement."

This leadership structure reached all over Spain. In every town, there was a "local chief of the movement." This person made sure the rules were followed in their area.

What Were Its Main Ideas?

People who strongly supported the Movimiento Nacional were often called Falangistas or Azules ("Blues"). This name came from the blue shirts worn by members of the Falange. The Falange was a group started by José Antonio Primo de Rivera before the Civil War.

Older members of the Falange were called Camisas viejas (Old shirts). Newer members were called Camisas nuevas (New shirts). Sometimes, the new members were accused of joining just for personal gain.

The main ideas of the Movimiento Nacional were summed up by a famous slogan: ¡Una, Grande y Libre! This slogan meant:

- Una (One): Spain should be a single, united country. It meant no regionalism or local governments.

- Grande (Great): Spain should be a powerful empire again. This looked back to the old Spanish Empire in the Americas and also looked forward to new territories in Africa.

- Libre (Free): Spain should be independent from outside influences. Franco believed in a "Judeo-Masonic-Marxist international conspiracy." This meant he thought groups like the Soviet Union, European democracies, and the United States (for a time) were enemies. He also saw many "internal enemies" within Spain, such as "anti-Spanish" people, "reds" (communists), "separatists," "liberals," "Jews," and "Freemasons."

Different Groups Within the Movement

Even though Franco's Spain had only one official party, different groups existed within the National Movement. These groups were often called "families" (Familias del Regimen). They competed with each other for influence. These families came from different right-wing political groups before the Civil War:

- Falangists: Also known as azules, they were very important in the FET y de las JONS party and the Spanish Syndical Organization.

- Traditionalists: These groups came from Carlism. They had a lot of control over the Ministry of Justice.

- Monarchists: These people wanted a king to rule Spain. They had strong connections to rich business people and the military.

- Catholics: These were groups closely linked to the Catholic Church.

In the 1950s, a new group appeared: the technocrats. These were conservatives linked to a group called Opus Dei. They focused on using business-like methods to run the government.

Franco kept his power by making sure no single group became too strong. He tried to balance their rivalries and not show too much favor to any one family.

Some members of these families eventually disagreed with Franco's government. For example, some Monarchists wanted a king to be crowned right away. Also, some Catholic groups joined the opposition against the dictatorship later on.

Minister-Secretaries General of the Movement

| No. | Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Term | Political party | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Took office | Left office | Time in office | ||||

| 1 | Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta (1896–1992) |

4 December 1937 | 9 August 1939 | 1 year, 248 days | National Movement | |

| 2 | Agustín Muñoz Grandes (1896–1970) |

9 August 1939 | 16 March 1940 | 220 days | National Movement | |

| Position vacant (16 March 1940 – 19 May 1941) |

||||||

| 3 | José Luis de Arrese (1905–1986) |

19 May 1941 | 20 July 1945 | 4 years, 62 days | National Movement | |

| Position vacant (20 July 1945 – 5 November 1948) |

||||||

| (1) | Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta (1896–1992) |

5 November 1948 | 15 February 1956 | 7 years, 102 days | National Movement | |

| (3) | José Luis de Arrese (1905–1986) |

15 February 1956 | 25 February 1957 | 1 year, 10 days | National Movement | |

| 4 | José Solís Ruiz (1913–1990) |

25 February 1957 | 29 October 1969 | 12 years, 246 days | National Movement | |

| 5 | Torcuato Fernández-Miranda (1915–1980) |

29 October 1969 | 3 January 1974 | 4 years, 66 days | National Movement | |

| 6 | José Utrera Molina (1926–2017) |

3 January 1974 | 11 March 1975 | 1 year, 67 days | National Movement | |

| 7 | Fernando Herrero Tejedor (1920–1975) |

11 March 1975 | 12 June 1975 † | 93 days | National Movement | |

| (4) | José Solís Ruiz (1913–1990) |

13 June 1975 | 11 December 1975 | 181 days | National Movement | |

| 8 | Adolfo Suárez (1932–2014) |

12 December 1975 | 6 July 1976 | 207 days | National Movement | |

| 9 | Ignacio García López (1924–2017) |

7 July 1976 | 13 April 1977 | 280 days | National Movement | |

See Also

In Spanish: Movimiento Nacional para niños

In Spanish: Movimiento Nacional para niños

- José Larrañaga Arenas

- Mottos of Francoist Spain

- Grand Council of Fascism, a similar governing body in Fascist Italy

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |