Maurici de Sivatte i de Bobadilla facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Maurici de Sivatte i de Bobadilla

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Maurici de Sivatte i de Bobadilla

1901 |

| Died | 1980 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | lawyer |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | CT |

Maurici de Sivatte i de Bobadilla (1901–1980) was an important Spanish politician. He was a leader of the Carlist movement in Catalonia, a region in Spain. He led the Catalan Carlists twice: first in the early 1930s, and then again in the 1940s. He also helped start a group called RENACE in 1958. This group was a part of the Traditionalist movement in Spain.

Contents

Maurici's Family and Early Life

Maurici de Sivatte's family came from France. They settled in Spain in the 19th century. His grandfather, Edmundo Félix Sivatte i Vilar, was born in Barcelona. Maurici's grandmother, María de las Mercedes de Llopart y Xiqués, was known for her charity work.

Maurici's father, Manuel Josép María de Sivatte i Llopart (1865-1931), was a lawyer in Barcelona. He became a leader of the Carlist movement in Catalonia. The Carlists were a group who supported a different royal family for the Spanish throne. In 1899, the Carlist claimant gave Manuel the title of marqués de Vallbona. Manuel helped start a newspaper called El Correo Catalán.

Maurici's mother was Margarita de Bobadilla y Martínez de Arizala (1870-1905). Her family was also Carlist. Maurici's maternal grandfather, Mauricio de Bobadilla y Escrivá de Romaní, led the Carlists in Navarre. Manuel and Margarita had five children, including Maurici. They were all raised in a very Catholic home. After their mother died young, their grandmother helped raise the children.

Maurici studied law at the Universidad de Barcelona. He became a lawyer in 1923. In 1924, he married Asunción Algueró de Ugarriza (1901-1970). They lived in the family home in Barcelona. They had 13 children! Some of their children became nuns and friars. One son, Rafael de Sivatte i Algueró, became a famous scholar of the Bible. Another son, Jaime de Sivatte i Algueró, became a successful businessman.

Starting in Politics

Maurici's father was a well-known figure in Barcelona society. This helped Maurici get involved in politics. In the late 1920s, Maurici joined a local Carlist group. He also worked with other Catholic groups. These groups wanted to protect traditional values.

In 1927, Maurici was a recognized member of Barcelona society. He took on important roles at local events. He also worked in a special organization called Organización Corporativa Nacional. This group helped solve problems between workers and businesses. He continued this work even when the government changed.

During the Republic

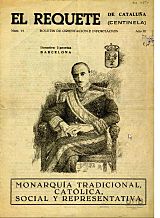

When the Second Spanish Republic began, it brought big changes. The new government was very secular, meaning it separated church and state. This made Maurici become even more active in the Carlist movement. In 1931, he helped start a weekly newspaper called Reacción. It aimed to support traditional values against new ideas.

In 1932, Maurici ran for the new Parliament of Catalonia but did not win. When different Carlist groups joined together to form Comunión Tradicionalista, Maurici became involved in their public events. He helped organize a Carlist meeting in Barcelona. He even became the vice-president, and later the president, of the main Carlist club in Barcelona. He was briefly arrested after a Carlist demonstration.

Maurici was known for his strong beliefs within the Catalan Carlist movement. He believed in sticking strictly to Carlist ideas. In May 1933, he became the leader of the Catalan Carlists. The Carlist leader, Don Alfonso Carlos, wanted new, energetic leaders. Maurici worked to build up the Carlist paramilitary group, the Requeté. But his leadership lasted less than a year. In March 1934, older politicians took back control. Maurici became the second-in-command.

As a deputy leader, Maurici focused on building the Requeté and promoting Carlist ideas. He often spoke at Carlist gatherings. He was against any alliance with other royalist groups. After the Popular Front won the elections, Maurici met with military leaders. They planned an uprising against the Republican government. Maurici wanted to completely overthrow the Republic. He also helped raise money for the planned military action.

The Civil War Years

Maurici was deeply involved in planning the Carlist rebellion in Barcelona and Catalonia. On July 18, 1936, he gave the orders for the uprising to begin the next day. The command of about 3,000 Carlist volunteers went to Cunill. However, the rebellion failed in Barcelona. The Carlist forces were scattered. Maurici went into hiding. In early August 1936, he managed to escape Catalonia by ship to Marseille, pretending to be a Polish citizen.

From France, Maurici went to the area controlled by the Nationalists. In September, he settled in San Sebastián. There, he helped create a Carlist committee to help Catalan exiles. He also moved to Zaragoza to help Carlist refugees. With Cunill, he had the idea to form a Requeté battalion made only of Catalans. This unit, called Terç de Requetès de la Mare de Déu de Montserrat, was formed in December 1936. Maurici worked hard to organize it. He also helped with Frentes y Hospitales, a Carlist group that helped wounded soldiers.

Maurici did not join the main Carlist wartime leadership. He was part of a group that strongly opposed being forced to join a new state party. This was a plan by Franco, the Nationalist leader. After Franco's Unification Decree in 1937, Maurici looked for ways to resist. He became the leader of the Catalan Carlists for the second time in 1938. As Carlism became less important under Franco, Maurici urged the Carlist regent, Don Javier, to take a stronger stand. He believed the regency was weakening the Carlist movement. He wrote letters asking Don Javier to declare himself the legitimate king.

Leading the Catalan Carlists

After the Nationalists took control of Catalonia, Maurici quickly went to Barcelona. He worked to rebuild the Carlist groups there. But the local military commander soon closed all the Carlist clubs. He ordered Maurici to leave Catalonia for a few months. This incident made Maurici believe that he could not work with Franco's new system.

Within the Carlist movement, Maurici led a group that refused to join any of Franco's organizations. They wanted to keep their Carlist identity separate. The government's reaction varied. In 1940, Maurici was arrested and put in prison. But in 1942, a general even joined him at a Carlist event. Relations between Catalan Carlists and Franco's party were often tense. Sometimes, this led to riots. Still, some say that Carlists in Catalonia had more freedom than elsewhere. They became the most active Carlist group in Spain.

In 1943, Maurici signed a document called Reclamación de Poder. This document asked Franco to end his government and bring back a Traditionalist monarchy. This was his last action as part of the main Carlist leadership. Maurici was worried about talks with other royalist groups. He feared a deal that would weaken the Carlist cause. So, in 1944, he resigned from the main Carlist leadership. But he remained the leader of the Catalan Carlists. He was also concerned that the Carlist movement lacked clear direction. He felt that Don Javier's regency was too inactive. In 1945, he wrote that Don Juan and Don Carlos Pio had no right to the throne. He urged Don Javier to take a strong and decisive stand. Maurici helped organize a large Carlist protest in Pamplona in December 1945. It ended in riots and arrests.

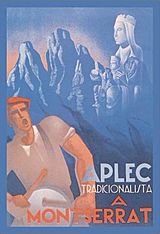

From 1947 to 1949, Maurici's relationship with Don Javier and the main Carlist leader, Manuel Fal Conde, got worse. Maurici wanted Don Javier to resolve the issue of his 11-year regency. He suggested calling a big Carlist meeting. But Fal Conde stopped this idea. Maurici also pushed for stronger action at the 1947 Aplec de Montserrat, a Carlist gathering. When Franco's Law of Succession was passed, Maurici believed it opened the door for another royal family to take the throne. This made him even more determined.

The 1948 Aplec de Montserrat was meant to be a strong show of Carlist independence. But the authorities banned it. The national Carlist leaders did not protest. In February 1949, Catalan Carlists sent another letter. Fal Conde tried to fix things, but he was told that Carlism could not continue on that path. In March 1949, Don Javier removed Maurici as the Catalan Carlist leader.

Becoming an Outcast

After 1949, Maurici either left the main Carlist organization or was expelled. Many of his supporters followed him. This left the main Catalan Carlist group much smaller. The split was clear because two separate Aplecs de Montserrat were held each year. One was for Don Javier's supporters, and one for Maurici's. Maurici's group was not a formal party. It was a loose group that met at a social club.

Maurici continued to hold his beliefs. He recognized Don Javier as the leader. But he was against the idea of a regency. He also opposed any compromise with other royal families or with Franco's government. He didn't get much support outside of Catalonia and parts of Navarre. This changed in the early 1950s. Many Carlists started asking Don Javier to end his regency. Even Fal Conde agreed. In 1952, Don Javier seemed to declare himself king during a big Catholic meeting in Barcelona. Maurici felt this was a victory. But Don Javier then seemed to back away from his declaration. This made Maurici question his loyalty to Don Javier.

Maurici remained strongly against Franco's government. In 1952, when a mausoleum for fallen Requetés was being built in Montserrat, Maurici opposed it. He felt it was part of Franco's propaganda. Because of his opposition, Maurici and his supporters were often arrested and fined. This stopped them from attending the Montserrat gatherings. In the mid-1950s, the main Carlist group started to try and work with Franco's government. Maurici's group strongly criticized this. They asked, "Has Don Javier given up his mission to General Franco?"

However, when Fal Conde was removed from his leadership role, relations with Don Javier's supporters improved. In 1956, Don Javier made friendly gestures towards Maurici. That year, the two groups agreed to hold a common Montserrat gathering.

In April 1956, Maurici's group met with Don Javier in Perpignan. Don Javier agreed to sign a document rejecting any compromise with other royal families or with Franco. But he refused to sign as a king. He also wanted to keep the document private. Maurici feared another change of heart. He refused to keep it private. Instead, he presented the document to a newly formed Carlist group. This group wanted to stop a pro-Franco turn in Carlism. Maurici published the Perpignan document as Manifesto a los españoles. At this point, he believed that loyalty to Don Javier was no longer working. He felt a new solution was needed.

Starting RENACE

After deciding to move on from Don Javier, Maurici looked for other options. In 1957, he talked with Don Antonio, another royal family member. But nothing came of it. Don Carlos Hugo, Don Javier's oldest son, appeared on the Spanish political scene in May 1957. Many of Maurici's supporters were very excited. Some rejoined Don Javier's group. But Maurici was suspicious of Don Carlos Hugo's pro-Franco ideas. In late 1957, a large group of Carlists declared Don Juan the legitimate heir. Maurici felt that true Carlism needed new energy right away.

On April 20, 1958, at the Aplec de Montserrat, Maurici announced the formation of Regencia Nacional y Carlista de Estella (RENACE). This group aimed to protect the true Carlist principles. It called itself the "supreme authority of the Carlist Communion." RENACE did not support any specific king or royal family. Its manifesto clearly stated, "we do not have a legitimate King." The group promised to protect the Carlist spirit from being changed. They especially opposed Franco's government, which they said had "failed essentially." They believed Don Javier was not truly opposing Franco. Maurici did not give many details about RENACE's goals or how it would work.

RENACE did not gain much support among Carlists. Its main base was in Catalonia. Some Traditionalist groups from other regions, like Navarre, also joined. No nationally known Carlist leader joined Maurici. However, some, like Joaquín Baleztena, supported him. In the early 1960s, it became clear that RENACE was just another small Carlist group. But its strong beliefs and opposition to Franco made it important for Traditionalists.

Initially, Maurici might have wanted RENACE to be a big political group. But its limited support changed this. RENACE became more of a symbol, a pressure group, and a group that developed ideas. Its public activities included publishing a magazine called Tiempos Criticos. It also issued manifestos and organized public rallies. These rallies were often presented as Catholic events. However, fewer and fewer people attended them over time. The group did not have a formal structure, except for its Supreme Council.

Later Years

In the 1960s, Maurici and RENACE continued to follow a very conservative Carlist path. They strongly opposed bringing back the Alfonsist monarchy. They also opposed any deal between Carlists and the Juanistas (supporters of Don Juan). Another key idea was their strong opposition to working with Franco's government. This opposition became more open as Franco's regime became more liberal. RENACE also focused on its very conservative Catholic beliefs. They were against the changes from the Second Vatican Council. They also strongly opposed any liberal or left-wing ideas. One of their favorite themes was fighting against "world revolution."

As late as 1964, Maurici tried to keep good relations with Don Carlos Hugo. But this attempt failed. Many of Maurici's supporters left RENACE and rejoined Don Javier's group. This was a big blow to Maurici. He became convinced that Don Carlos Hugo was a leftist traitor. He strongly opposed Don Carlos Hugo's efforts to take control of Carlism. This even led to Maurici and Fal Conde becoming somewhat closer.

Over time, RENACE became more and more isolated. It failed to attract young members. It became a group of older members. In 1970, it seemed to get a boost when different Carlist groups met. But the meeting only produced a few documents. It was overshadowed by the growing power of the socialist-controlled Partido Carlista. In 1973, only 150 people showed up to the main annual RENACE event at Montserrat. The next year, Maurici was arrested and fined at the same event. This was perhaps the last time he received any political recognition.

After Franco died, during the transition to democracy, RENACE remained strongly against democracy. They supported the idea of an anti-democratic, Catholic Traditionalist government. Some say that Maurici's group, which had always been against Franco, paradoxically became closer to Franco's old supporters as his regime was dismantled. In 1978, RENACE formed a political party called Unión Carlista. But it remained a very small group. Maurici suffered from diabetes and was unable to move easily by the end of his life. But he still attended every Montserrat gathering until he died in 1980.

See also

In Spanish: Mauricio de Sivatte para niños

In Spanish: Mauricio de Sivatte para niños

- Carlism

- Francoism

- Don Javier

- Manuel Fal Conde

- Regencia Nacional y Carlista de Estella

- Monastery of Montserrat

- Terç de Requetès de la Mare de Déu de Montserrat