Miguel Junyent Rovira facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

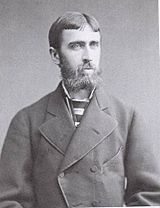

Miguel Junyent Rovira

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Born |

Miguel Junyent Rovira

1871 Piera, Spain

|

| Died | 1936 (aged 64–65) Barcelona, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | lawyer, publisher |

| Known for | politician, publisher |

| Political party | Comunión Tradicionalista |

Miguel Junyent Rovira (Catalan: Miquel Junyent i Rovira) (1871–1936) was a Spanish Catalan publisher and politician. He was from Catalonia, a region in Spain.

He is best known for being the director of El Correo Catalán. This was a newspaper he owned and managed for many years. He worked there between 1903 and 1933.

As a politician, Miguel Junyent was part of a group called Carlism. He was the main leader of this party in Catalonia. He held this role from 1915 to 1916 and again from 1919 to 1933. He was elected to the Spanish parliament, called the Cortes, two times. He was a member of the Congress of Deputies from 1907 to 1910. Later, he was a member of the Senate from 1918 to 1919.

He was seen as a moderate Carlist. This means he preferred to work with other conservative groups. He did not support the more extreme or violent parts of his own party.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Miguel Junyent's family, the Junyents, were known in Catalonia since the 1200s. However, it is not clear if they were his direct ancestors. We know that his father was Salvador Junyent Bovés (1836-1900). Salvador lived his whole life in Piera, a town in Catalonia. He was a landowner and part of the local upper-middle class. He owned a property called Can Perevells.

Salvador married Prudencia Rovira Oller (1837-1914). She was from Cornella de Llobregat. Miguel had at least one sister, but we don't know how many children his parents had in total.

We do not know much about Miguel's childhood or his early schooling. In the late 1880s, he started studying law at the Barcelona University. He finished his law degree around 1895. In 1897, he officially became a lawyer in Barcelona. By the late 1800s, he was working as a lawyer.

Before 1898, Miguel Junyent married Joaquína Quintana Padró (1874-1912). We know very little about her or her family. They lived in Barcelona and had three children. Sadly, their oldest daughter died when she was very young.

After Joaquína passed away, Miguel remarried Mercedes Canalías Vintró (died 1934) before 1916. She was a widow, and they did not have any children together.

His son, José María Junyent Quintana (1901-1982), became a Carlist politician in the 1930s. He also became well-known as a journalist and writer. His younger daughter, María de Montserrat Junyent Quintana (1905-1985), married Juan Baptista Roca Caball. He was a famous politician in Catalonia later on.

Miguel Junyent's grandson, Miguel Roca Junyent, became a very important politician. He helped write the Spanish constitution in 1978. Another grandson, Miguel Junyent Armenteras, became a top executive in Catalan finance.

Starting in Public Life (1894-1906)

We don't know what political ideas Miguel's ancestors had. However, his father seemed to be a Traditionalist. Young Miguel was active in conservative groups while he was still a student. By 1894, he was a leader in the youth branch of the Carlist party in Barcelona.

In the mid-1890s, he was involved in religious activities. He also gave speeches at local Carlist clubs. People liked his speeches, and some important party members noticed him. This is how he got the attention of Luis Llauder y Dalmases. Llauder was the regional Carlist leader and owned El Correo Catalán.

Llauder invited Junyent to write for El Correo, and soon he became a regular writer. When Llauder's health got worse, the newspaper was taken over by a Carlist organization. In 1903, its president, Duque de Solferino, made Junyent the new director of El Correo.

As the head of El Correo Catalán, Junyent became a key figure in Catalan Carlism. He was also an important voice for the party across Spain. He often appeared with other Carlist leaders at rallies and meetings. At first, his political views were similar to the main party ideas. He supported Catholic religion and traditional values.

In 1906, Junyent represented the Traditionalists in talks with other Catalan political groups. They wanted to form a common front against a new law called Ley de Jurisdicciones. This law put certain offenses against the army and state under military courts. In Catalonia, many people saw it as an attack on their region and its identity.

Junyent became one of the leaders of this movement. He worked with Francesc Cambó to go to Madrid and coordinate actions with other politicians. Later that year, the Catalan opposition formed Solidaritat Catalana. This was a group of local parties against the new law. Junyent pushed for his party to join this group. He was the only Carlist who signed the document that created the alliance. He also joined the main leadership group of Solidaritat.

Political Roles and Challenges (1907-1915)

Before the 1907 elections, Catalan Carlists were divided. They debated whether to join forces with republicans and nationalists in the Solidaritat group. Junyent strongly supported this alliance. He convinced the new regional leader, Janer, to allow Carlists to join.

Junyent ran for election in Vic and won easily. The Carlists joining Solidaritat was a big success for the party. Six Carlists were elected in Catalonia alone. Junyent became one of the most important Traditionalist leaders in the region. He also became known on the national political scene. In parliament, he mostly spoke about Catalan or religious issues.

From 1908 to 1909, Solidaritat slowly fell apart. The parties in the alliance started to have different goals. Carlists worried more and more about working with parties that seemed to want Catalonia to separate from Spain. Junyent tried to calm these fears. He said that for local Traditionalists, Catalonia was like a sister province to all others, and Spain was their common mother.

However, by 1909, he also had serious doubts. El Correo started to argue more with Catalan nationalists. Some of Junyent's articles became very strong, criticizing those he saw as cowards. By the 1910 elections, Solidaritat was gone. Junyent only managed to make a local alliance with another party, La Lliga. He tried to win his seat in Vic again, but he lost by a small margin. His complaints about unfair voting did not help.

In the early 1910s, Junyent was part of a moderate group of Catalan Carlists. This group was led by Duque de Solferino. Their opponents in the party, led by Dalmacio Iglesias, wanted to use street violence against radical republicans. Iglesias wanted to turn the new paramilitary group, Requeté, into a fighting force. This led to a street battle in Sant Feliú de Llobregat in 1911.

Junyent and his group tried hard to control the more extreme members. They succeeded mostly because they had a very good relationship with the new Carlist king, Don Jaime. Junyent traveled to Venice to meet Don Jaime when he became the claimant to the throne. In 1914, he went to Viareggio to get instructions on how Carlists should spread their message during the Great War. As a former member of parliament and director of El Correo, Junyent also spoke at party rallies across Catalonia.

Leading the Catalan Party (1915-1919)

Because of internal conflicts, Solferino resigned as the Catalan party leader in 1915. Junyent, who was his closest helper and very loyal to Don Jaime, was chosen to take his place. Immediately, he faced attacks from three groups within the party. Some radicals accused him of being too soft on conservative regionalists. Others criticized his leaning towards nationalist groups. And a new group, the Mellistas, disliked his strong loyalty to Don Jaime. Even though El Correo Catalán supported Germany in the war, not the Entente, these groups still opposed him.

All these groups looked to Iglesias as their leader. When the national party leader, Marqúes de Cerralbo, supported Iglesias as a candidate in the 1916 elections, another crisis happened. In the end, the entire regional committee, including Junyent, resigned. Solferino was then put back as the Catalan leader.

Even with changes in leadership, Catalan Carlism continued to break into smaller groups in the late 1910s. By 1919, there were at least three main groups. Junyent's group, the Jaimistas, stayed loyal to Don Jaime. There was also the Ateneo group and the Mellista group led by Iglesias.

Junyent carefully tried to find a path between different extreme ideas. He avoided violent city uprisings and nationalist movements. He also avoided the Mellista idea of a big far-right alliance. He tried not to weaken the Traditionalist ideas by joining unclear middle-class groups. He criticized nationalists who claimed to represent all of Catalonia. But he also tried to keep good relations with La Lliga, another political party.

Thanks to La Lliga's support, Junyent was elected to the Senate in 1918. He was still listed as a lawyer at this time. His entry into the Senate happened when the Mellista group was causing big problems within Carlism. In early 1919, de Mella and his supporters left to form their own group. This weakened the Carlist party leadership across the country.

Junyent remained loyal to Don Jaime. He took part in a big meeting in Biarritz to decide the party's future. For the second time, he was named the Catalan leader. This time, his leadership of regional Carlism would last for 14 years.

Senate, Mancomunitat, and City Council (1919-1923)

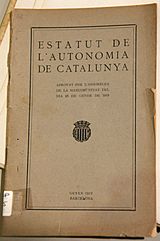

In the Senate, Junyent was not very active in the chamber's daily work. However, he was very involved in talks between the Cortes and a new Catalan government-like body called Mancomunitat. In 1918, Junyent joined the committee that wrote the Bases d’Autonomia de Catalunya. This document was about Catalonia's self-rule. He also joined a special committee set up by the Cortes to discuss Catalan self-governing rules.

Junyent supported the idea of Catalonia declaring its own self-rule. He thought pushing the project through the Madrid parliament would weaken it. In 1919, he, along with Cambó and Lerroux, became a key leader of this project. They joined a joint committee and edited the self-rule text for a public vote. Together, they also decided to pause the self-rule campaign in spring 1919. This was because of a major strike and social unrest in the region. His term in the Senate ended in 1919, and he did not try to be re-elected.

In his public work, including supporting the Mancomunitat's self-rule efforts, Junyent acted for the Carlists. In 1920, as the Mellista split continued to hurt the party, he stressed his full loyalty to Don Jaime. In El Correo Catalán, he said that Traditionalists must stay united behind their leader. He led or attended private Traditionalist meetings and public rallies. From 1920 to 1921, he remained active in the Mancomunitat, which was becoming less effective.

At this time, he was becoming worried about social and political changes in Spain. In the early 1920s, El Correo criticized the growing chaos. Junyent himself almost died in a bomb attack meant for the civil governor. It seems that El Correo Catalán was his own property by then. He was also involved in a bank called Banco Catalán, where he was the president.

In early 1922, Junyent ran for the Barcelona ayuntamiento (city council) as a Traditionalist. He was elected. The same year, he was made a deputy mayor, a position he kept in 1923. He kept his balanced political views. In the city hall, he had good relations with moderate Catalanists from La Lliga. He supported the ideas of their former leader, Prat de la Riba, even with some disagreements.

Junyent was flexible and willing to compromise. In June 1923, when the city council was in crisis, he offered to resign as deputy mayor. He also helped Traditionalist trade union members from Sindicatos Libres who were having trouble with the police. As a Barcelona councilor, Junyent also hosted his king, Don Jaime, during the claimant's five-day visit to the city in July 1923.

During the Dictatorship (1923-1931)

Like many Carlists, Junyent seemed to welcome the start of Primo de Rivera's dictatorship. He was worried about the growing political chaos and social unrest. In mid-1923, he took part in a Somatén event with the Barcelona military leader.

However, his cautious support began to fade after the new government's first actions. By the end of 1923, he was removed from the Barcelona city council. His career there ended after less than two years. In 1924, the government banned the use of the Catalan language in public offices. This led him to sign an open letter demanding that the language be freely used. Also in 1924, he was put on trial for an article he wrote in El Correo Catalán in 1918. The article had called for Spain to stay neutral during the Great War, but the prosecutor accused Junyent of encouraging rebellion. The outcome of this case is not known.

At this time, Junyent stayed in close contact with his king, Don Jaime. In late 1923, he traveled to Paris to get instructions on how Carlists should act towards the dictatorship. He made the same trip in early 1924 and again later that year. In the mid-1920s, the party's stance towards the government changed. First, they decided not to participate, and then they became critical.

As the Catalan regional leader, Junyent issued orders telling party members not to join official government groups. He also introduced a type of internal party censorship. This was to make sure all Carlist newspapers in Catalonia had the same message. As director of El Correo Catalán, he tried to promote this view in his newspaper, within the limits allowed by censorship.

His own public activities were mostly limited to Traditionalist or religious gatherings. For example, in 1925, he led a large Carlist pilgrimage to Rome. However, in 1926, he was noted as having met with the minister of interior. The reason for this visit is not known.

There is little information about Junyent's public activities in the late 1920s. He continued as the Carlist Catalan leader and was honored as a distinguished leader. He remained among the key national party politicians who met Don Jaime, for example, during his visit to the claimant's home in Frohsdorf.

Junyent usually avoided risky plans. In the late 1920s, he helped stop a plan for an uprising in Seu d’Urgell. This plan was being considered by some young, eager Carlists. When the dictatorship ended and a milder government took over, he continued his efforts for Catalan self-rule. In 1930, when leaders of Catalan provinces met to try and restart the Mancomunitat, Junyent wrote in El Correo that the Catalan problem needed a "complete and final solution." He also noted that Catalonia, with its own language, laws, flag, and spirit, "is Spanish because it is deeply Catalan." In February 1931, he joined a new committee to work on a self-rule law.

During the Republic (1931-1933)

Junyent was very doubtful about the start of the Republic. In late 1931, he stated that the new parliament was "extreme and dictatorial" in politics, society, and religion. He felt they were passing laws "against the traditional feeling and spirit of our people."

Although he did not encourage violence, he was arrested after riots in Barcelona involving Carlist youth. He spent a short time in a prison ship called Dédalo and was released in December 1931. In 1932, members of the Sanjurjo conspiracy asked him to cooperate. Junyent refused, saying he did not have enough people or authority. This did not stop him from being detained again until after the coup attempt. He was detained one more time in 1933 after more riots and police action against Carlist clubs.

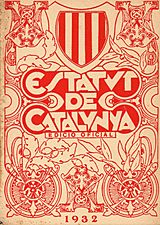

Despite his concerns about the republican ideas in the draft of the Catalan self-rule law, Junyent decided to support it in the referendum. He called it a "true, though limited, affirmation of Catalonia’s identity." He also quieted a group of Carlist youth, including his son, who opposed the plan. He made sure that party messages emphasized Catalan regional features.

However, he was very worried about the law's secularism (separation of church and state). He also feared that the self-governing region would fall under the control of extreme left-wing groups. He tried to fight this by promoting many Traditionalist activities. For example, he organized the Gran Setmana Tradicionalista in spring 1932. He also joined conservative groups like Propaganda Cultural Católica. He tried to rebuild an alliance with La Lliga, based on protecting religion, law, and order. This plan did not work. To his regret, La Lliga chose to ally with the Radicals in the 1932 Catalan elections. Junyent ran in the election himself, but both his personal results and the overall Carlist results in the region were very poor.

Junyent's moderate approach, his support for self-rule, and his desire to ally with the middle-class La Lliga caused more and more arguments among Carlist members in Catalonia. This was made worse by his comments about a possible merger between the two "Bourbon branches" (different royal families). Even though the late Don Jaime and his successor considered this idea, opposition against Junyent grew from 1932 onwards. He was even booed at party rallies.

His main opponents accused him of working with "liberal parties" and being too submissive to them. They also criticized his Catalanism and the poor election results in 1932. This campaign against him was well-planned. Some opponents even traveled to France to convince the king to remove him. Junyent himself seemed tired and upset. He tried to resign twice. His third resignation letter was finally accepted. In June 1933, Junyent stopped being the Catalan Carlist leader.

Later Years (1933-1936)

By the late 1920s, Junyent had to reduce his public activities because of his health. After no longer being the Catalan Carlist political leader, he slowly withdrew from active politics. His last known attendance at a regional party meeting was in late 1934.

His new roles in the party were more advisory. In 1933, Don Alfonso Carlos asked him to lead a special advisory board for Catalonia, but it probably never fully formed. In 1934, he was named to the Council of Traditionalist Culture. This was a group of thinkers meant to protect the party's core ideas. His rare public appearances were sometimes related to current politics. For example, in late 1933, he took part in an election rally for the Right. In 1934, he joined a rally to remember Carlists killed during the October Revolution. However, Junyent's public appearances were increasingly separate from daily events. For instance, in 1935, he took part in a tribute to Juan María Roma.

After 30 years as the head of El Correo Catalán, Junyent also stopped being the newspaper's director in 1933. It is not clear why he left. We do not know if he resigned, was forced to resign, or was fired. It is also unclear who owned El Correo when he left.

His business activities included being president of Banco Catalán Hipotecario. This bank was known as "the Carlists' bank" because of its political and personal connections. Junyent also had to manage his Can Perevells estate in Piera. This estate had increasing problems with conflicts with the farm workers. Finally, Junyent was involved in the Societat Económica Barcelonesa d’Amics del Pais and the Institut Agricola Catalá de Sant Isidre.

It is not known if Junyent was involved in or aware of the Carlist plans against the Republic. It is also unclear if the July 1936 coup surprised him. One source says he had already left politics by then. There are different stories about where he was after the coup. One source says he stayed in Barcelona and attended a bank meeting. He tried to resign over issues related to employee compensation during the unrest, but his resignation was not accepted. Another source says he went into hiding.

One story claims that a militia group came to his home to arrest him. However, they reportedly left because Junyent was in poor health. Shortly after, he suffered a fatal heart attack. This happened after he learned that his successor as the Carlist Catalan leader, Tomás Cayla, had been killed by the Republicans. One day later, another group came to arrest or execute him. They only completed their mission when they were led to a room where Junyent's body was being prepared for his funeral. The different accounts of this event vary.

See also

In Spanish: Miguel Junyent para niños

In Spanish: Miguel Junyent para niños

- El Correo Catalán

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |