Tomàs Caylà i Grau facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tomàs Caylà i Grau

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Tomàs Caylà i Grau

1895 |

| Died | 1936 Valls, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Citizenship | Spanish |

| Occupation | publisher |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | Comunión Tradicionalista |

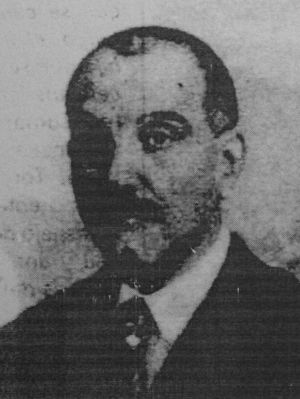

Tomàs Caylà i Grau (1895-1936) was a Spanish publisher and a Carlist politician. Carlists were a group in Spain who supported a different line of the royal family. They believed in traditional values and a strong Catholic faith.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Tomàs Caylà i Grau came from a well-off family in Catalonia, Spain. His grandfather, Tomás Caylá y Sardá, was a businessman in Tarragona. He was involved in politics and was even a mayor of Reus.

Tomàs's father, Josep Caylà i Miracle, studied law and worked in Valls. He became a director at a local bank. He also helped local farmers and landowners. Josep was a very religious man. He believed in traditional values and helping the community. He passed away in 1919.

Tomàs grew up in a very religious home. Both his parents were strong Catholics. After finishing school, Tomàs went to Barcelona to study law in 1911. He became a lawyer in 1916 and started working in his hometown of Valls. People knew him for being honest and dedicated.

He was very active in Catholic groups. He even helped start a local review called Estel Maria. Tomàs never married. He said he wanted to dedicate his life to God and to the Traditionalist cause. This meant he wanted to support the traditional way of life and beliefs in Spain.

Starting a Newspaper and Politics

In 1919, Tomàs and other young people in Valls started a weekly newspaper called Joventut. The newspaper was small, only four pages. Its motto was "For faith and for the homeland." It was published in Valls and other parts of the Tarragona region.

Tomàs was the main person behind Joventut. He managed it, wrote many articles, and organized everything. He often wrote under pen names like "C.V." or "Almogáver." The newspaper shared his political ideas. It said its members were first Catholic, then Spanish, then Catalan, then Traditionalist, and finally Legitimist. This showed their strong beliefs in religion, Spain, their region, and traditional ways.

In 1920, Tomàs tried to become a member of the Valls city council. He ran as a Carlist candidate. He was not elected that time. However, in 1922, he tried again and was elected. He was one of the most popular candidates.

His time on the council was short. In 1923, Miguel Primo de Rivera became dictator of Spain. This meant elected officials were replaced by people chosen by the government. Joventut criticized the new government. In 1924, Tomàs was even arrested and spent five days in prison. He was also sent away from his home for a month. Joventut continued to criticize the government and faced fines and suspensions.

When Primo de Rivera's dictatorship ended, Tomàs was allowed back on the city council. He became active in public life again. He believed that Catholic principles should guide Spain. He supported the Vatican and the Pope's teachings. He was against Liberalism, which he saw as going against traditional values.

He was loyal to the Carlist king, Jaime III. However, he was not as vocal about monarchy as other Carlists. He believed it was more important to work for Spain, whether it was a kingdom or a republic. He wanted a new constitution based on traditional values.

The Second Spanish Republic

In 1931, the monarchy fell, and the Second Spanish Republic was created. Many Carlists were happy about the fall of the old monarchy. Tomàs was different from most Carlists. He was not hostile to the new Republic. He hoped it would become a true democracy.

In his newspaper, Tomàs was careful about the new government. He accepted that most Spaniards wanted a republic. He asked his fellow Carlists to wait and see if the Republic would become an orderly state. He warned that extreme views were the biggest enemy of the new government.

However, the Republic became very secular, meaning it separated church and state. This made Tomàs an opponent of the Republic. He also felt that Republicans and Socialists in the Valls council were too dominant. In 1932, he tried to get elected to the Parliament of Catalonia but failed. He had to leave the local council and criticized the growing chaos in Valls.

Tomàs started to see Traditionalism as the only way to stop a revolution. He believed the government was controlled by groups that did not serve Spain's interests. As Joventut's views became stronger, it faced more problems. It was suspended for supporting a military uprising in 1932. It also faced heavy fines and more suspensions.

Tomàs became an important Carlist politician in Catalonia. In 1931, he became the head of the Carlist party in Tarragona. He helped reorganize the Comunión Tradicionalista. He also ordered the Carlist paramilitary group, the Requeté, to mobilize during the October 1934 uprising. He criticized the Catalan government for causing chaos.

Tomàs was very busy organizing and speaking at Carlist meetings in 1934 and 1935. One large meeting in Poblet in June 1935 had 40,000 people. By then, the Carlists in Tarragona had 30 local groups and 4 newspapers. In March 1936, Tomàs became the new regional leader of the Carlists in Catalonia.

Catalan Identity

Tomàs Caylà wrote a lot about the question of Catalan identity. This was almost as important to him as his strong Catholic faith. He always supported Catalan culture and political goals. But he always combined this with the idea of Spain's national interest.

In 1919, Tomàs said his Catalan identity was third in importance. It came after being Catholic and Spanish. This showed he believed being Catalan and Spanish went together. He supported Catalan self-rule. For Tomàs, separate regional governments were part of the Carlist vision.

He imagined Catalonia being connected with Castile. The king in Madrid would rule as the Count of Barcelona. But he would have to respect Catalonia's local laws, called fueros. The regional parliament would decide on administrative, financial, and economic matters. Local towns would also have a lot of freedom.

During the dictatorship, Tomàs continued to support Catalan goals. He was sympathetic to Francesc Macià, a Catalan leader. He criticized the government's actions against Macià. He kept his vision for Catalan self-rule, which he wrote about in Joventut in 1930. Some people even thought his ideas were close to supporting full independence.

However, the way the Catalan issue developed during the Republic disappointed Tomàs. He supported talks about a new self-rule law. But he did not join the strong anti-Spanish movement in Catalonia. He was against separatism. He believed Catalan rights should come first, not be under the Spanish constitution.

He was also unhappy that the self-rule law was secular. He accepted the statute but saw it as a step towards his own vision. He was disappointed with the final law and how the Catalan government acted. He was worried by the actions of Lluís Companys and the Catalan Left. He called their actions "left-wing fascism."

Social Issues

Tomàs Caylà cared deeply about social issues. He saw these problems as a result of modern societies moving away from religion. He believed that people were trying to replace God with false ideas. He thought Liberalism was the main cause of problems. He saw it as anti-Christian and leading to the suffering of working people.

He believed that left-wing movements, like Anarchism, Socialism, or Communism, were misleading people. He thought they offered false ideas of freedom.

According to Tomàs, there were two ways to solve social problems: the Socialist way and the Christian way. He preferred the Christian way, which was based on the Pope's teachings in Rerum novarum and Quadragesimo anno. Instead of fighting between social classes, the Christian way offered a peaceful society. This would be achieved through Catholic principles and various regulating groups.

Tomàs believed in Christian trade unions and groups for both employers and employees. In Valls, he helped set up a Carlist social group called Agrupació Social Tradicionalista. He encouraged cooperative businesses. He also supported new Christian unions in Tarragona.

Last Months and Legacy

There are different stories about Tomàs Caylà's role before the July 1936 coup. Some say he joined the plot against the Republic after the Popular Front won the elections. He hoped the uprising would succeed. Others say he was against joining the military rebellion but was outvoted by Carlist leaders.

Another story says he did conspire with generals. But he thought the uprising was too early. He urged them to act only if the Left tried a coup first. The most detailed account says that in early 1936, Tomàs was worried by the Republic's direction. But he did not want to join a conservative rebellion against it.

During the July 1936 coup, the Catalan Requeté group was ready to fight. Tomàs was leading the Carlists in Catalonia. He learned about the uprising from the radio. He left the leadership of the Requeté to another leader, José Cunill. The coup failed in Barcelona. Carlist volunteers were scattered, some killed, some captured, and some went into hiding.

Tomàs first stayed in his hotel. But when he heard that other Carlist leaders were captured, he realized the danger. He hid with relatives in Barcelona. He refused to leave the Republican zone. He felt it would be a betrayal of the Traditionalist cause. He decided to face whatever came next.

In early August, a group in Valls started looking for him. They found his letters and learned where he was hiding. A group of militia members went to Barcelona and arrested him. In mid-August, Tomàs was driven back to Valls. He was executed in Plaça del Pati immediately after arriving.

After his death, Tomàs Caylà was remembered in a book published in 1938. It praised him as a hero for Catholic and national causes. After the Nationalists won in Catalonia in 1939, Tomàs and other people from Valls who died were re-buried. A street in Valls was named after him, and it still is today.

In the 1940s, Tomàs was a hero for Carlists in Tarragona. Later, in the 1960s, his memory became important again. Supporters of a young Carlist prince, Carlos Hugo, tried to redefine Carlist history. They presented Tomàs Caylà as a true Carlist. They said he was tolerant, humanist, progressive, democratic, and against capitalism.

A second book about him was published in 1997. It also praised him, but with a different view. Some groups on the far Left in Spain and Catalonia also see Tomàs Caylà as someone who came before their own movements. However, other left-wing groups still see him as an enemy. There is an effort today to remove streets named after him in Catalonia.

See also

In Spanish: Tomás Caylá para niños

In Spanish: Tomás Caylá para niños

- Carlism

- Catalanism

- Fiesta patronal

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |