Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Most Excellent

The Marquess of Cerralbo

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa

1845 Madrid, Spain

|

| Died | 1922 Madrid, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | politician |

| Known for | archaeologist, politician |

| Political party | Carlism |

Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa (1845 – 1922) was an important Spanish person. He was known as the Marquess of Cerralbo. He was a talented archaeologist, someone who studies old things, and a Carlist politician. Carlism was a political group in Spain that supported a different royal family.

Contents

A Young Nobleman's Life

Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa came from a very old and important family in Spain. His family had lived in the Salamanca area for hundreds of years. In 1533, one of his ancestors was given the title of "marquis" by King Charles I.

Enrique's father, Francisco de Asís de Aguilera y Becerril, started a special gym in Madrid. He was known for inventing many machines to help people exercise. Enrique was one of 13 children.

Education and Family Titles

Enrique first went to school at the Colegio de las Escuelas Pías de San Fernando in Madrid. Later, he studied Philosophy, Letters, and Law at the Central University.

When his father died in 1867, Enrique became the oldest son. He received the title of "conde de Villalobos." This meant he was part of the important noble families and had enough money to live comfortably.

A few years later, in the early 1870s, Enrique's life changed even more. His two uncles died without children, and then his grandfather, José de Aguilera y Contreras, also passed away. Enrique became the most senior male in his family line.

He inherited the title of Marquess of Cerralbo. He also received many other noble titles. Because of these titles, he became a "Grandee of Spain." This was a very high rank in the Spanish nobility.

Wealth and Marriage

Enrique also inherited a lot of money and land from his grandfather. This included estates in southern Leon and a palace in Salamanca. This made him one of the richest and most important people in Spain.

He became even wealthier when he married Manuela Inocencia Serrano y Cerver in 1871. She was 30 years older than him and had children from a previous marriage. They traveled a lot and started building a grand family home in Madrid.

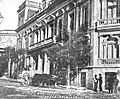

In 1893, they moved into their new home, which was like a palace. It was designed to be an art gallery, similar to other private art collections in Europe. This palace also became a place for important social gatherings and political meetings. Enrique and Manuela did not have any children together.

Early Political Life as a Carlist

Even though his father's family supported Queen Isabella II, Enrique's mother encouraged him to join the Carlist movement. He joined in 1869 and also helped start a Catholic youth group.

In 1871, he tried to become a member of the Spanish parliament, called the Cortes, but he didn't win. However, he won a seat in the next elections in 1872. He only served for two months because the Carlist leader, Carlos VII, told his supporters to resign before a planned uprising.

There is no clear information about whether Enrique took part in the Third Carlist War. In 1876, he met Carlos VII in Paris. They became good friends. Enrique was one of only two "Grandees" who supported Carlism, making him a very important figure in the movement.

Challenges and Leadership

Within the Carlist movement, Enrique tried to focus on religious causes. However, he faced challenges from Cándido Nocedal, who became the main leader, called "Jefe Delegado," in 1879. Nocedal wanted the Carlists to stick to their old ways, while Enrique wanted them to be more open to new ideas.

When Cándido Nocedal died in 1885, many thought Enrique would become the new leader. But Carlos VII decided to lead the movement himself. Enrique stepped back from politics for a while, partly due to health reasons.

In 1885, he became a member of the Senate because of his high noble rank. He was the only Carlist in the Senate at that time. In 1888, Carlos VII asked Enrique to create a new official Carlist newspaper, El Correo Español. This started a lifelong friendship with Juan Vázquez de Mella.

Enrique also worked on many other Carlist cultural projects. He traveled across Spain in 1889-1890 to gather support, which was a new way to get people involved. Sometimes, he was even attacked by people who supported the Republic. In 1890, Carlos VII made Enrique the "Jefe Delegado," giving him a lot of power to lead the Carlist movement.

Leading the Carlist Movement

As the leader, Enrique tried to work with other conservative political groups. He focused on getting Carlists elected to parliament, even though they didn't win many seats in the elections of 1891 and 1893.

He understood that public opinion was becoming more important. He worked to improve Carlist propaganda, which is how they spread their ideas. He tried to organize Carlist newspapers, libraries, and publishing houses. He also used public activities like lectures, feasts, and even monuments to promote their cause.

Modernizing the Party

Enrique was one of the first to use images in Carlist propaganda. He made sure that portraits and photographs of Carlist leaders, including himself, were printed and shared widely. He also tried to build financial support for the movement by selling shares in Carlist-controlled organizations.

One of Enrique's biggest achievements was building a nationwide Carlist organization. Before him, Carlism was more like a loose group of leaders. Enrique helped create formal structures with thousands of local groups called juntas and circulos. This made Carlism one of the most modern political parties of its time in Spain. This change led many people to call it "new Carlism."

In 1897, Enrique oversaw the creation of the Acta de Loredán, an important document that explained Carlist beliefs. It confirmed their very conservative views, their commitment to religion, the royal family, and a decentralized state. It also tried to include the social teachings of the Church and bring back some former supporters.

Challenges and Resignation

As the crisis in Cuba grew, some newspapers warned that the Carlists might start another uprising. Enrique tried to prevent this. The Carlist leader, Carlos VII, did not want to weaken Spain while it was at war with the United States.

However, after the terrible peace treaty of 1898, Carlos VII seemed to be preparing for another Carlist war. Enrique was seen as a leader who wanted peace, while others wanted war. He was rumored to be dismissed. Citing health reasons, he left Spain and resigned as "Jefe Delegado" in late 1899. Carlos VII accepted his resignation and appointed a new leader.

A Break from Leadership

Enrique left Spain in mid-1900 and was not there during La Octubrada, a failed Carlist uprising in October 1900. He thought the uprising was too early, even though he didn't rule out violent action in general.

He continued to be a member of the Senate. He returned to Spain in early 1901 and continued his work in the Senate. His relationship with Carlos VII remained good, but they grew apart. Enrique stayed loyal to the Carlist leader and his new "Jefe Delegado."

He also became good friends with Carlos VII's son, Don Jaime, because they both loved history and archaeology. After a period of poor health, Enrique became more active in the mid-1900s, leading the Carlist group in parliament. When the current "Jefe Delegado" died in 1909, many thought Enrique would return to the top leadership role. However, Carlos VII chose someone else.

Second Time as Leader

When Carlos VII died in 1909, Enrique's political future changed. He advised the new Carlist leader, Don Jaime, to use the name Jaime III as king. Many important Carlists urged Don Jaime to bring Enrique back as leader.

Don Jaime agreed in 1912 and created a new governing body, the Junta Superior Central Tradicionalista, with Enrique as its president. Many people believed Enrique was the real leader, even if he wasn't officially called "Jefe Delegado." Some thought that another important Carlist, de Mella, believed Enrique would be easier to influence because he was older and sick.

Enrique returned to his policy of working with other conservative parties. He also started touring Spain again and reorganized the party. He introduced new ways to make the party more visible, like organizing large gatherings and pilgrimages. During his second time as leader, the Requete, a paramilitary organization, was formed.

World War I and Internal Conflicts

When World War I started in 1914, Enrique wanted Spain to stay neutral. He sympathized with the Central Powers (like Germany and Austria-Hungary) because he thought their monarchies were closer to the Carlist ideal. He also traditionally opposed Great Britain.

He faced a difficult task of keeping the Carlists united, as some in the movement, including Don Jaime himself, supported the Allies. Another disagreement Enrique had to solve was in Catalonia, about how to deal with local nationalism.

The most difficult issue was the growing conflict between de Mella and Jaime III. Enrique found it hard to choose sides. He was also dealing with health problems and felt hurt by attacks from his former friends. In the spring of 1918, he resigned again, citing health reasons.

When the Mellistas broke away from the Carlists in 1919, Enrique was no longer in a leadership position. He did not take a clear side and left politics completely. Although Don Jaime did not openly criticize him, he privately said harsh words about Enrique. However, de Mella spoke in Enrique's defense. Enrique did not attend the important Carlist meeting in Biarritz in 1919. His last public role was being appointed mayor of the Argüelles district in Madrid in 1920.

Archaeologist and Historian

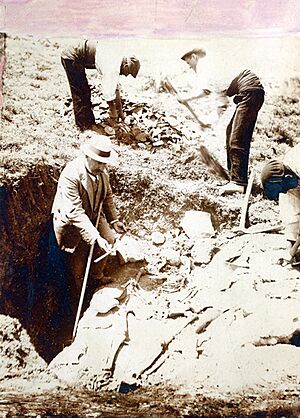

Since his university days, Enrique was very interested in culture and history. He first became involved in archaeology in Madrid in 1895. He started collecting old objects found during building demolitions. He also organized his own archaeological digs. The first ones were in the upper Jalón valley, starting in 1908.

His biggest success was finding the Celtiberian site of Arcóbriga. This ancient city had been searched for by many people since the 16th century. Based on his careful studies, Enrique correctly found the site. Digs continued there for many years.

In 1909, he started excavations at Torralba del Moral and Ambrona. These continued until 1916. At that time, these sites were thought to be the oldest human settlements ever found in Europe. A famous book about ancient humans, El hombre fossil (1916), was partly based on Enrique's discoveries. He also helped promote, fund, and direct many other archaeological sites.

New Methods and Recognition

Even though Enrique's digging methods are now considered old-fashioned, he introduced new techniques. He used photography at the dig sites and in the lab. He also developed complex ways to organize and catalog his findings. He worked with many experts, including geologists, historians, and paleontologists, sharing his discoveries with scientific groups.

Enrique became a member of many scientific organizations. Famous archaeologists from around the world visited him in Madrid and Soria. In 1912, he was recognized for his five-volume work, Páginas de la Historia Patria por mis excavaciones arqueológicas. He was also praised for his work on Torralba at an international conference in Geneva that same year.

The Ministry of Education asked him to help create a new law about excavations. This law, passed in 1911, helped prevent ancient objects from being taken out of Spain. It also created new organizations to oversee archaeological research. Enrique himself led several archaeological institutions. He also published studies on historical figures and a monastery. In 1908, he joined the Royal Academy of History, and in 1913, the Real Academia Española. Before he died, Enrique donated part of his archaeological collection to public museums.

A Man of Many Hobbies and Collections

From a young age, Enrique wrote for Madrid newspapers and magazines. He was active in a literary society and wrote short stories and poems. One of his poems even appeared in a Spanish poetry collection. His writing style mixed classic poetry with romantic feelings, which was popular at the time.

Enrique spent a lot of time at his country home in Santa María de Huerta. There, he enjoyed gardening and farming, especially horse breeding. He tried to create a new type of horse by mixing English and Spanish breeds. In 1882, his horses won a top prize at an exhibition in Madrid. In 1902, his horses won more prizes in Madrid and Barcelona.

Passionate Collector

Since childhood, Enrique loved to collect things. At first, he collected coins, but then he started collecting many other items. These included paintings, weapons, armor, porcelain, ceramics, rugs, tapestries, marbles, watches, lamps, sculptures, furniture, rare books, stamps, and other antiquities.

Enrique was always looking for new items. He found them at auctions, antique shops, and museums across Europe. He even bought entire collections from other people. He gathered around 28,000 objects, and his collection was considered one of the most complete in Spain at the time. Newspapers called him "The Collector Marquess."

Before he died, Enrique set up the Fundación Museo Cerralbo. This foundation still displays most of his collection today. The collection shows how people collected things in the 19th century. It gives a sense of a search for beauty and a good quality of life. Guidebooks today describe the museum as a place filled with "the fruits of the collector’s eclectic meanderings."

His Lasting Impact

Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa is remembered for his important contributions to archaeology. He made key discoveries and introduced modern digging methods. As a politician, he is praised for using new ways to get people involved and for trying to bring different groups together, which was unusual for the Carlists. He is also recognized as someone who gave part of his collection to public museums and founded his own museum.

Some critics say that he supported old-fashioned ideas. They also point out that he avoided taking clear sides during important moments of crisis, often saying he had poor health. They might also say his collection was just a way to show off his wealth. Some also argue that he used archaeology to promote nationalist ideas. Finally, some suggest that Enrique was part of a powerful group that kept Spain's social and economic conditions old-fashioned, and that he personally benefited from his privileged position while others were poor.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa para niños

In Spanish: Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa para niños