Electoral Carlism (Restoration) facts for kids

Electoral Carlism during the Restoration was a key part of keeping the Carlist movement alive in Spain. This was between the end of the Third Carlist War in 1876 and the start of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship. After losing the war, the Carlists changed their focus. They stopped fighting and started using political methods and media campaigns.

They decided to work within the political system of the Alfonsine monarchy. Elections, especially for the Congress of Deputies, became their main way to get people involved. Even though the Carlists had very few members in the Spanish Parliament, their election campaigns were important. They helped the party stay strong until it became more powerful again during the Second Spanish Republic.

Contents

How Elections Worked in Spain

During the Restoration period, Spain's election system aimed for one deputy to represent about 50,000 people. The lower house of parliament, the Congress of Deputies, had around 400 deputies. These deputies were the only ones fully elected by the people.

Electoral districts usually matched the existing judicial districts. There were two types of districts:

- 279 distritos rurales (rural districts) elected one deputy.

- 88 circunscripciones (larger districts) elected several deputies. The number depended on how many people lived there. In these districts, voters could choose more than one candidate.

In both types, the person with the most votes won. This is called the first-past-the-post system. Provinces and regions did not play a direct role in the election process.

Who Could Vote?

Before 1891, only Spanish men over 25 who paid certain taxes could vote. These taxes were called "contribución territorial" in rural areas or "subsidio industrial" in cities.

After the 1891 election, all men over 25 could vote. This increased the number of possible voters from 800,000 to 4.8 million. This meant about 27% of the entire population could vote.

Election Problems: Turnismo and Caciquismo

Spanish elections during this time had two main problems:

- Turnismo: This was a system where two main parties, the Conservatives and the Liberals, took turns running the government. They made sure their party won the majority in parliament. They did this using many tricks, known as pucherazos (electoral fraud).

- Caciquismo: This was a system of political corruption. Local party bosses, called caciques, controlled votes in their areas.

These problems made elections unfair. Rural areas often had more electoral fraud. The Carlists were outside this system. They did not get the special treatment that the two main parties received. While there were a few local Carlist bosses, caciquismo generally worked against the Carlists.

How Well Did Carlists Do?

| Carlist votes | |||||||||||

| year | votes gathered | year | votes gathered | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1879 | 536 | 1903 | 44,846 | ||||||||

| 1881 | 2,197 | 1905 | 29,752 | ||||||||

| 1884 | did not run | 1907 | 87,923 | ||||||||

| 1886 | 456 | 1910 | 69,938 | ||||||||

| 1891 | 24,549 | 1914 | 52,563 | ||||||||

| 1893 | 45,617 | 1916 | 69,938 | ||||||||

| 1896 | 43,286 | 1918 | 90,122 | ||||||||

| 1898 | 40,481 | 1919 | 90,423 | ||||||||

| 1899 | 11,915 | 1920 | 70,075 | ||||||||

| 1901 | 45,576 | 1923 | 52,421 | ||||||||

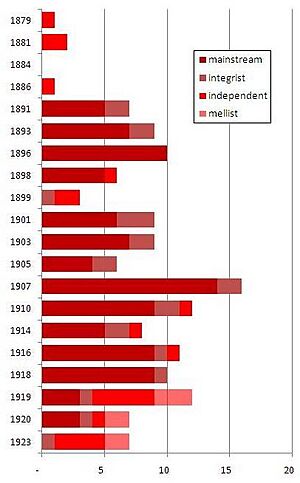

Between 1879 and 1923, there were 20 general elections. A total of 8,048 seats were available in parliament. All Carlist groups together, including the main Carlists, Integrists, Mellists, and independent candidates, won 145 seats. This was only 1.8% of all seats.

This put the Carlists far behind the two main parties, the Conservatives and the Liberals. Each of these parties won over 3,500 seats. The Carlists also did worse than various republican and democratic parties, which together won about 500 seats.

So, Carlism was the fourth largest political group. However, they won more seats than newer parties like the Catalanists, Basques, or Socialists. These parties only gained strength later in the 20th century.

Carlist Voter Numbers

It's hard to know exactly how many votes the Carlists received. This is because of fraud and the way votes were counted. In the 1890s, winning Carlist deputies usually got around 40,000 votes in each election. If you include votes for candidates who didn't win, the number was probably closer to 50,000. This would be about 1.7% of all active voters.

In the 20th century, winning Carlists received about 65,000 votes on average. In 1907, 1918, and 1919, this number was around 90,000. This suggests that up to 100,000 people might have voted for Carlism, which was about 4% of all active voters. Even though this wasn't a huge number, the Carlist voters were still more numerous than, for example, the Socialist voters. Before the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, the PSOE (Socialist party) never attracted more than 40,000 voters.

Carlist Strength Over Time

From a national view, the Carlists were always a small group in parliament. They couldn't really change national politics. Only their best speakers sometimes made an impact.

However, from the Carlists' own view, their number of seats in parliament changed a lot. It could be anywhere from 1 to 16. These changes often depended on how well they did in Navarre. In other regions, their strength stayed pretty much the same. For example, Vascongadas usually elected 2-3 Carlist members, Catalonia (except in 1907) 1-2, and Old Castile 1.

The Restoration era can be divided into four periods based on the number of Carlist deputies.

Early Years (1879-1891)

In these years, very few Carlist deputies were elected. They won as individuals, not as part of an official party effort. The first one was Baron de Sangarrén in 1879. The Carlist movement was still recovering from its defeat in the Third Carlist War. Their newspapers were shut down, clubs closed, and supporters exiled.

Recovery was also hard because of growing disagreements between the Carlist leader Carlos VII and the Nocedal family (father and son). This led to the Integrist group breaking away in 1888. Because of this, only a few deputies were elected from Guipuzcoa, Álava, and Biscay until 1891. Carlists did support candidates from other parties, and they were strong in local elections in some provinces.

Growing Competition (1891-1907)

The split with the Nocedalistas made both the Integrists and the main Carlists try harder in elections. The year 1891 was their first official campaign. Both groups were very hostile towards each other. Carlos VII and Ramón Nocedal even told their followers to team up with Liberals if it meant defeating their former Carlist friends.

This approach slowly changed in the late 1800s. In the 20th century, both groups started working together against new government laws. Still, between 1891 and 1907, both Carlist groups combined never won more than 10 seats in one election. The main Carlists won 44 seats in total, and the Integrists won 12.

Peak Performance (1907-1920)

The 1907 election was the best for the Carlists during the Restoration period. This happened for two reasons:

- The Carlists gained almost complete control of Navarre. Both Carlist groups won 6 out of 7 seats there. They willingly let the Conservatives win the last one.

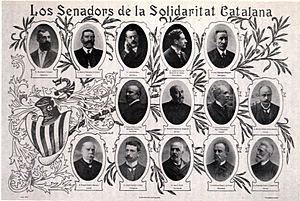

- In Catalonia, the Carlists joined a regional alliance. This boosted their Catalan seats from the usual one or two to six.

Even though this alliance broke up a few years later, the Carlists still did well. A quick but temporary growth in the Valencian Carlist group, along with their continued strength in Navarre and closer ties with the Integrists, helped them. This allowed Carlism to hold 10-12 seats in the lower house of parliament for most of the time until 1920.

Decline (1920-1923)

The final years, from 1920 to 1923, saw the Carlist group shrink. Another split, the Mellista secession, hurt Carlism badly. Many leaders and regional bosses left to join the new group.

In Navarre, their traditional stronghold, the Carlists tried short-term alliances, even with Liberals. This confused voters, and Carlism lost its strong hold on the province. Basque and Catalan movements also became more careful about working with Carlism. Finally, new rivals like the Republicans and Socialists started to take away Carlist voters in the Northern and Eastern provinces.

In the last election of 1923, Jaime III, the Carlist king, told his followers not to vote. He said he was disappointed with the corrupt democracy.

What Carlists Believed and Who They Teamed Up With

At first, Carlists didn't focus on a detailed political plan. They simply said that only Traditionalism could truly represent local interests in Madrid. They often highlighted the "Fueros" part of their beliefs, which meant supporting local rights and traditions. This was seen in their support for the Fueristas in the 1880s, local alliances in the 1890s, Solidaritat Catalana in 1907, or Alianza Foral in the 1920s.

However, their support for local traditions never meant they fully supported independence for regions like Vascongadas or Catalonia. This often caused problems in their relationships with nationalist groups. Another common theme in Carlist messages was defending the rights of the Roman Catholic Church and promoting Christian values. They tried to be seen as the only true "Catholic" party. They also criticized bishops for giving this label to Liberal candidates. Their claims to the Spanish throne were usually kept quiet, and they avoided openly challenging the current king.

As the turnista system became more corrupt, Carlist messages in the 20th century focused more on political corruption. They said this was a natural result of liberalism. Carlist candidates were always very ultra-conservative and anti-democratic. As the new century began, their campaigns became even more reactionary. They often called for defending traditional values against a "red revolution."

In the late 1910s and early 1920s, Carlists used many tactical alliances. They put aside their strong beliefs and focused on practical issues. On the other hand, the Integrists strongly criticized the main Carlists for teaming up with their old enemies, the Liberals. In the final years of the Restoration, the Carlists openly rejected the political system, calling parliament a "farce."

Carlist Alliances

There was no single way Carlists formed alliances throughout the Restoration period.

- Early on: When they didn't run their own candidates, Carlists mostly supported right-wing Conservatives, local groups defending regional identities, or independent Catholic candidates. Liberals were always their main enemies.

- After the 1888 split: Both the main Carlists and the Integrists saw each other as the main enemy. They fought bitterly, sometimes even supporting Liberals to defeat the other Carlist group.

- Early 1900s: Their hostility began to fade around 1899, first locally in Guipuzcoa, then nationally. In the early 20th century, the two groups allied again against the Liberals, especially against the Ley de Jurisdicciones (a law about military courts).

- Wider alliances: Opposing liberal governments made Carlists put aside their dislike for Republicans and their caution towards Catalanism. Joining Solidaritat Catalana led to their largest number of parliamentary seats in 1907. However, this group broke up a few years later. Similar alliances in Galicia or Asturias were not as successful.

- Later years: Regional alliances, often with Integrists, Mauristas (followers of Antonio Maura), and independent candidates, continued until about 1915. In the last years of the Restoration, the main Carlists made tactical alliances, even with Liberals and Nationalists. This angered the Integrists. The Mellista split further divided the Carlists.

Where Carlists Were Strongest

| Most Carlist districts | |||||||||||

| no | district | success | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Azpeitia (Guipuzcoa) | 85% | |||||||||

| 2 | Tolosa (Guipuzcoa) | 65% | |||||||||

| 3 | Estella (Navarre) | 60% | |||||||||

| 4 | Aoiz (Navarre) | 40% | |||||||||

| 4 | Cervera de Pisuerga (Palencia) | 40% | |||||||||

| 6 | Pamplona (Navarre) | 38% | |||||||||

| 7 | Olot (Gerona) | 30% | |||||||||

| 7 | Laguardia (Alava) | 30% | |||||||||

| 9 | Tafalla (Navarre) | 25% | 10 | Vich (Barcelona) | 20% | ||||||

The Carlists' support was very uneven across Spain. They had almost no presence in most of the country. They were a small but steady force in some provinces. They truly thrived in only one area. Generally, Carlism had some electoral strength in the North-Eastern part of Spain, from the Bay of Biscay, along the Pyrenees mountains, to the Central Mediterranean coast.

The main areas of Carlist support were Vascongadas (the Basque Provinces) and Navarre. These two regions elected 94 Carlist members of parliament, which was 65% of all Carlist deputies.

- Navarre: This region elected 35% of all Carlist deputies. It was the only area where the movement truly controlled local politics. Although Carlism was almost non-existent there in the 1880s, by the end of the century, Carlists controlled about 35-40% of Navarre's seats. In the first two decades of the 20th century, they became the main force, winning 60-80% of seats in each election. They even played a deciding role in local politics by forming alliances with other parties. Within Navarre, the Carlist stronghold was the Estella district. It was one of only three districts in all of Spain where Carlism won the majority of seats during the Restoration period.

- Vascongadas: The two Vascongadas provinces where Carlism aimed for control were Guipuzcoa and Álava.

* In Guipuzcoa, the Carlists won 33 seats. This was 33% of all seats available in the province during the period and 22% of all Carlist seats won in the Restoration. The rural districts of Azpeitia and Tolosa were local strongholds, with the highest Carlist success rates in all of Spain. * In the smaller Álava province, Carlists won about 15% of the available seats. However, they often dominated local elections, especially in the 19th century. * In Biscay, another Vascongadas province, support for the Carlists was quickly declining. They only elected a Carlist member twice from Durango.

| Most Carlist regions | |||||||||||

| no | region | success | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Navarre | 36.4% | |||||||||

| 2 | Vascongadas | 15.7% | |||||||||

| 3 | Catalonia | 2.7% | |||||||||

| 4 | Valencia | 1.7% | |||||||||

| 5 | Baleares | 1.4% | |||||||||

| 6 | Old Castile | 1.3% | |||||||||

| 7 | León | 0.4% | |||||||||

| 7 | Asturias | 0.4% | |||||||||

| 9 | Andalusia | 0.0% | |||||||||

| 9 | Aragon | 0.0% | |||||||||

| 9 | Canarias | 0.0% | |||||||||

| 9 | Extremadura | 0.0% | |||||||||

| 9 | Galicia | 0.0% | |||||||||

| 9 | Murcia | 0.0% | |||||||||

| 9 | New Castile | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Most Carlist provinces | |||||||||||

| no | province | success | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Navarre | 36.4% | |||||||||

| 2 | Guipuzcoa | 33.0% | |||||||||

| 3 | Álava | 15.0% | |||||||||

| 4 | Palencia | 8.0% | |||||||||

| 5 | Gerona | 5.7% | |||||||||

| 6 | Castellón | 2.9% | |||||||||

| 7 | Barcelona | 2.5% | |||||||||

| 7 | Tarragona | 2.5% | |||||||||

| 9 | Valencia | 2.3% | |||||||||

| 10 | Biscay | 1.7% | |||||||||

Other Regions with Some Carlist Presence

Regions where Carlism had a small presence (1-3% of available seats) included Old Castile and the Levantine coast, which covers Catalonia, Valencia, and the Balearic Islands.

- Catalonia: Carlists elected 23 deputies here. This was 16% of all Carlist members of parliament, but only 3% of all Catalan seats. In Gerona, Carlists got 6% of seats. In Barcelona and Tarragona, they got 3%. In Lerida, it was only 1%. The most Carlist districts in Catalonia were Olot and Vich.

- Valencia: This region was behind Catalonia in terms of Carlist success. It was a bit stronger in Castellón province (3%) than in Valencia province (2%). Carlists had some success in Nules and Valencia city. The 1919 election was their most successful in Valencia, winning 3 seats (9% of the total).

- Balearic Islands: This small region elected 2 Carlist members from Palma.

- Old Castile: Carlists won 11 seats here, which was 1.3% of all available seats. This was mostly due to 8 wins in Cervera de Pisuerga, one of the top 5 Carlist districts in the country. This also made Palencia one of the top 5 Carlist provinces. Carlists also elected one deputy in Santander, Valladolid, and Burgos.

Regions with Little or No Carlist Presence

Two regions had only 1-2 Carlist members elected, meaning the movement was barely there: León and Asturias. In these northern areas, the Carlist share of seats was less than 1%.

No Carlist deputies were elected in Andalusia, Galicia, Aragon, New Castile, Murcia, Extremadura, and the Canary Islands. Carlism was also not very popular in large cities. The 10 biggest Spanish cities (with 10% of the population) elected only 10 Carlist deputies, which was 7% of all Carlist members.

Important Carlist People

During the Restoration period, 64 different people were elected as Carlist deputies. Some served only one term, while others were long-time parliament members. The four deputies who served the longest held 25% of all Carlist seats during this time.

- Joaquín Lloréns was elected 3 times from districts in the Levante region. Then, he served 8 times in a row from Estella in Navarre. He holds the record for the longest-serving Carlist deputy ever (24 years) and the most times elected (11 times).

- Vázquez de Mella was elected 7 times from Navarre and once from Oviedo.

- Matías Barrio was the Carlist political leader from 1899 to 1909. From 1891 to 1909 (except 1903–1905), he was elected from his home district of Cervera de Pisuerga in Palencia. He led the Carlist group in the lower house of parliament.

- Manuel Senante represented the Integrist branch. Although he was from Alicante, he continuously served for 16 years from Azpeitia in Guipuzcoa. Along with Llorens, he holds the title of the most continuously elected Carlist deputy (8 times).

Carlist leaders didn't always run for parliament. Cándido Nocedal didn't run after the 1876 defeat. Marqués de Cerralbo had a guaranteed seat in the Senate because of his noble title. Matías Barrio did run between 1901 and 1907 (but lost in 1903). Bartolome Feliu Perez won in 1910. Pascual Comin didn't compete in 1919. Luis Hernando de Larramendi lost in 1920. Marqués de Villores was told by the Carlist king not to vote in 1923.

Leaders of the breakaway Carlist groups often ran for parliament. The first Integrist leader, Ramón Nocedal, won 4 times but also lost some elections. The next leader, Juan Olazábal Ramery, preferred not to run. After breaking away from the main Carlists in 1919, Vazquez de Mella failed in his attempt to get into parliament.

| Most elected Carlists | |||||||||||

| no | name | elected | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Joaquín Lloréns Fernández | 11 | |||||||||

| 2 | Matías Barrio y Mier | 8 | |||||||||

| 2 | Manuel Senante Martínez | 8 | |||||||||

| 2 | Juan Vázquez de Mella | 8 | |||||||||

| 5 | Luis García Guijarro | 5 | |||||||||

| 5 | Cesáreo Sanz Escartín | 5 | |||||||||

| 5 | Ramón Nocedal y Romea | 5 | |||||||||

| 8 | Narciso Batlle y Baró | 4 | |||||||||

| 8 | Tomás Domínguez Romera | 4 | |||||||||

| 8 | Pedro Llosas Badía | 4 | |||||||||

| 8 | José Sánchez Marco | 4 | |||||||||

| 8 | Josep de Suelves i de Montagut | 4 | |||||||||

| 13 | Joaquín Baleztena Ascárate | 3 | |||||||||

| 13 | Esteban Bilbao Eguía | 3 | |||||||||

| 13 | Miguel Irigaray Gorría | 3 | |||||||||

| 13 | Víctor Pradera Larumbe | 3 | |||||||||

Three times, both a father and son served as Carlist members of parliament. First were the Ortiz de Zarate family, Ramon and Enrique, both representing Vitoria in Álava in the 19th century. Then came the Ampuero family, José María and José Joaquín, from Durango. The Dominguez family, Tomas and Tomás, represented Aoiz in Navarre.

Only 5 politicians served in parliament both before and after the Third Carlist War. Some politicians who started their careers during the Restoration continued to serve until the late 1960s. The most famous example is Esteban Bilbao, who later became president of the Francoist parliament. His first and last days in parliament were 49 years apart.

Sometimes, Carlist deputies won their seats without any competition. This happened most often in Navarre (8 times). In districts like Estella and Aoiz, potential opponents sometimes recognized Carlist dominance and didn't even bother to run. Occasionally, the famous Article 29 (a law that allowed candidates to win without a vote if they were unopposed) was used elsewhere. For example, it helped Senante in Azpeitia or Llosas Badia in Olot. Joaquín Llorens had the most overwhelming victory, winning 99.51% of votes in 1907.

Most Carlist deputies were landowners, lawyers, academics, and journalists. There were fewer business owners, officials, or military men. Most of them started their parliamentary careers in their 30s.

Why Carlism Succeeded (or Didn't)

Many experts try to understand why Carlism was popular (or not). They often look at social and economic conditions, though their conclusions can sometimes be different.

The common idea is that the movement did well in rural areas with large shared lands and medium-sized farms. These farms were at least self-sufficient and often sold goods in the market. This type of farming provided a stable economic base for peasant owners, who were the main supporters of Carlism. These conditions were common in Northern Spain.

However, where small, unsustainable farms, landless peasants, or farmworkers became common (like in New Castile or Andalusia), Carlism lost its base. In industrial areas, rapid social changes weakened traditional ways of life and reduced Carlist popularity. Growing numbers of city workers, though not completely against Carlist ideas, tended to prefer anarchism and socialism.

Culture and Religion

Another set of reasons for Carlist support relates to culture and religion. Carlism was strongly linked to religious belief, which was strongest in the Northern provinces. Poor peasants in Extremadura, Andalusia, or New Castile had largely stopped being devout Catholics.

Groups who didn't care much about religion, or were even against it, like the socially mobile middle-class professionals in cities during the early Restoration, were less likely to support Carlism. In the 20th century, industrial workers contributed to the growing secularization of big cities. This explains why Carlism wasn't popular in Madrid, Barcelona, Seville, Málaga, Zaragoza, or Bilbao.

However, the idea that Carlists were always anti-city isn't true everywhere. Some experts note that in parts of Spain like Galicia, the movement was absent in rural areas but found support only in medium-sized cities like Ourense.

Experts who study Carlism and regional movements agree that for a while, they supported each other. The debate is mostly about when they started to drift apart. Was it when regional identities became more about ethnicity, or even later, when ethnic groups started demanding political rights? It's also unclear why this connection was strong in some regions but weak in others, like Galicia.

Recently, historians have become more skeptical about putting too much emphasis on socio-economic conditions. They now think this view might be too simple. Some point to a "new political history" that focuses on family patterns, shared beliefs, religious and moral values, and daily life. Others suggest a return to political analysis as the main way to understand Carlism. One expert prefers to look at how cultural symbols helped Carlism gain support, especially among less privileged people.

See also

In Spanish: Carlismo electoral (Restauración) para niños

In Spanish: Carlismo electoral (Restauración) para niños

- Carlism

- Electoral Carlism (Second Republic)

- Carlo-francoism

- Integrism (Spain)

- Mellismo

- Restoration

- Navarrese electoral Carlism

- Turno

Images for kids

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |