Tomás Domínguez Arévalo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

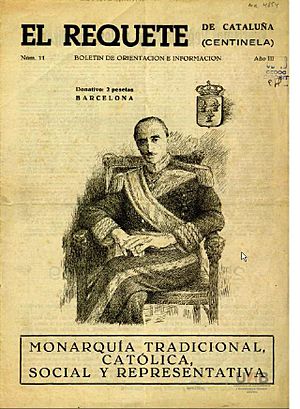

The Most Excellent

The Count of Rodezno

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Tomás Domínguez Arévalo

1882 |

| Died | 1952 Villafranca

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | landowner |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | CT |

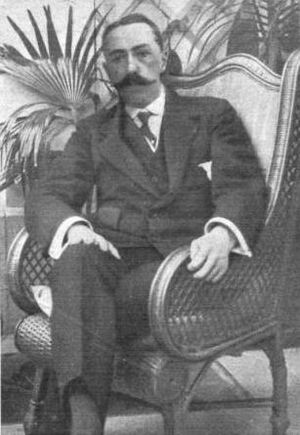

Tomás Domínguez Arévalo (1882–1952) was an important Spanish politician. He was known for being a Carlist and later a Francoist. Carlism was a political movement that supported a different royal family for Spain. Francoism was the political system led by Francisco Franco after the Spanish Civil War.

Tomás Domínguez Arévalo was the first Minister of Justice under Franco's government from 1938 to 1939. He also played a big part in getting the Carlists to join the military uprising in July 1936. This led to a group called "Carlo-Francoism," which were Carlists who worked with Franco's government.

Contents

Family and Early Life

Tomás Domínguez Arévalo came from two wealthy families who owned a lot of land. His father's family, the Domínguez, had lived in Carmona in Seville for a long time. His father, Tomás Domínguez Romera (1848–1931), inherited a large estate there. He supported the Carlists during the Third Carlist War and had to leave Spain for a while.

Later, his father married María de Arévalo y Fernandez de Navarrete (1854–1919). Her family, the Arévalos, were from La Rioja and Navarre. María's father, Justo Arévalo y Escudero, was a well-known conservative politician. He served in the Spanish parliament, called the Cortes, and was a senator from Navarre for many years. When Tomás's parents married, María was already the Countess of Rodezno (condesa de Rodezno). This meant Tomás Domínguez Romera became a count through his marriage.

It's not clear if Tomás grew up in Madrid or in Villafranca, Navarre. He went to school at the Jesuit Colegio de San Isidoro in Madrid. Later, he studied law at the University of Madrid. He graduated in 1904. Even though he was called a "lawyer," it's not known if he ever worked as one.

In 1917, Tomás married Asunción López-Montenegro y García Pelayo. She came from a rich family of landowners from Cáceres. They settled in Villafranca and had one child, María. When his mother died in 1919, Tomás inherited the title of Count of Rodezno (conde de Rodezno). After his father died in 1931, he also became the Marquis of San Martín (marqués de San Martín).

Starting in Politics

Tomás Domínguez Arévalo didn't do much in public life during the early 1900s. He was likely involved with youth groups for Carlists. In 1909, he published a book about medieval rulers of Navarre. He also wrote articles about Navarre's history and worked as a literary critic for newspapers in Pamplona. Some people say he was the mayor of Villafranca, but this is not confirmed.

Tomás's political career was helped by his family. His grandfather was a well-known politician, and his father was one of the most important Carlist politicians in Navarre. His father was so influential that his election district was almost like his personal property.

In 1916, Tomás's father decided not to run for parliament again. Tomás Domínguez Arévalo took his place as the Carlist candidate. Some people criticized him, saying he was too flexible with his political views. Even so, he was elected to the Cortes. He was re-elected in 1918.

At this time, the Carlist movement was having problems. There was tension between a main Carlist thinker, Juan Vázquez de Mella, and the Carlist leader, Don Jaime. Tomás was on de Mella's side. Some historians believe he thought Carlism was dying out because the Carlist royal family might not have any more heirs. He wanted a big group of right-wing parties to work together. However, when the movement split in 1919, he chose to stay loyal to Don Jaime.

In the 1919 election, Tomás lost his seat by a very small number of votes. In 1920, he lost again, which showed that the Carlists were losing power in Navarre. A week after this defeat, he ran for the Senate, which is the upper house of parliament. He was elected and re-elected in 1922. He didn't do much as a senator. One of his few actions was about taxes on cork exports, which was something he cared about because he produced cork on his land in Andalusia.

During the Dictatorship

When Miguel Primo de Rivera became dictator in 1923, Tomás Domínguez Arévalo's time in parliament ended. He stepped away from politics and didn't join any of the dictator's organizations. However, he stayed active in public life. He participated in Christian activities, supported cultural projects, and remained involved with Carlist groups. He also continued his work as a writer and historian, while managing his family and businesses.

Tomás was a member of the Catholic nobility and was active in the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. He had good relationships with Church leaders in Spain. He was especially close to Pedro Segura, a powerful archbishop. Tomás helped organize Catholic social groups and gave talks at events.

His cultural activities often had a Carlist theme. He organized events to honor veterans of the Third Carlist War. He also helped raise money for a monument to Vazquez de Mella, a Carlist thinker. He became well-known for his historical writings. In 1928, he published a book about the Princess of Beira, and in 1929, a book about Carlos VII, both important Carlist figures. These books are still used by historians today.

Tomás and his wife owned land in different parts of Spain: Navarre, Extremadura, and Andalusia. He was known as a "prominent landowner." He led groups for Catholic farmers and landowners in Navarre. He also talked with government ministers about farming issues and wrote studies on land ownership. He believed that Navarre's land system, where many farmers owned their land, was ideal.

Becoming a Carlist Leader

During the time of the "Dictablanda" (a softer dictatorship after Primo de Rivera), the Carlists became more active. In 1930, a new Carlist group was formed in Navarre, with Tomás as a member. This group wanted to focus more on religious issues and less on Basque nationalism.

When the Second Spanish Republic was declared in 1931, the Carlists formed an election alliance with another party. This allowed Tomás to be elected to the Cortes again in 1931. In parliament, he was less supportive of Basque autonomy than other Carlist deputies. He stopped supporting a plan for regional self-rule when it didn't allow for independent religious policies.

In 1932, different Carlist groups reunited into a new organization called Comunión Tradicionalista. Tomás was appointed to its main leadership group. After the leader, the Marquis of Villores, died in May 1932, Tomás was chosen as the president. This made him the effective political leader of the Carlists.

Tomás was very worried about the threat of revolution and believed that democracy couldn't stop it. He liked the idea of strong, authoritarian governments. He was especially against the Republic's anti-religious policies and land reforms. He was a strong opponent in parliament and once had a glass thrown at him. He traveled around the country, saying that "Carlist shock troops are ready to defend society against Marxist threat." However, he didn't push for an uprising. He knew about a planned military coup but avoided direct involvement. Even so, the government took some of his property afterward.

As leader, Tomás focused more on politics and public relations than on building up the Carlist organization. Some scholars say that the Carlist group's old structure couldn't handle its fast growth. There was also disagreement within the party about his attempts to work with other monarchist groups. In April 1934, Tomás agreed to step down as leader. He remained the local Carlist leader in Navarre.

The Uprising and Civil War

Even though Tomás's supporters complained about the Carlists becoming more "fascist-like" under the new leader, Fal, the movement shifted from political talks to building up its organization, including its military wing. Tomás was not given a leadership role in these new sections.

Tomás was re-elected to the Cortes in 1933 and 1936. He became the head of the Carlist group in parliament. He was allowed to continue private talks with other monarchist groups. In 1936, these talks started to become about planning a joint uprising.

Tomás played a very important role in getting the Carlists to join the military coup. Talks between General Mola and Fal had stopped because they couldn't agree on the terms. So, Mola started talking directly with the Carlist leaders in Navarre, led by Tomás. Tomás and the Navarrese leaders went around Fal. They offered the support of the Carlist militia (the requetés) if they could use the monarchist flag and if Navarre would remain a Carlist area. Fal was outmaneuvered when Tomás and the Navarrese got conditional support from the Carlist regent, Don Javier. In the end, Mola and Fal decided to work together.

During the coup, Tomás was in Pamplona, a city easily taken by the rebels. Even though Fal thought Tomás was disloyal, he had to include him in the new Carlist wartime executive group in August. Tomás was in charge of handling relations with the military government and local authorities. He moved to the military headquarters in Salamanca.

The Carlists first thought they would be equal partners with the military. But within a few months, they realized they were becoming less important. Their attempt to keep their independence failed in December 1936. After Fal decided to set up a Carlist military academy, he was told by Francisco Franco that he would be executed or exiled. Tomás and his supporters pushed for Fal to accept exile.

Joining Franco's Party

With Fal in exile and the Carlist leadership taken over by Don Javier in France, Tomás became the most important Carlist figure in Spain. Starting in January 1937, the military and the Falangists (Franco's party) began to pressure Tomás and other Carlist leaders to join a single state party.

The Carlist leaders met three times to discuss this challenge. Tomás and his group wanted to agree to the political merger that the military was pushing for. They were opposed by Fal's supporters, who wanted to resist. Because the formal Carlist leadership was falling apart, Tomás's group in Navarre became very important. This led to the unification. The merger was presented as a way to build a new state that would be Catholic, respect regional differences, and eventually become a Traditionalist monarchy.

On April 22, Tomás was named to the Political Secretariat of the new party, Falange Española Tradicionalista. He was one of only four Carlists in the ten-member group. He and other Carlists only learned about the party's program after it was announced, and they were uneasy about it. His relationship with Fal and Don Javier became very strained. They saw him as a rebel. Tomás tried to get approval from the Carlist regent, Don Javier, but he failed.

Over the next few months, Tomás saw that the Carlists were being absorbed into the Falange, not truly merging. He received many complaints from Carlists about the Falangists' dominance. In October 1937, Franco created a new governing body for the party, the National Council of the Movement. Despite Fal's calls to refuse, Tomás accepted a seat. In December 1937, Don Javier expelled him from the Carlist movement. Tomás ignored this.

Tomás's reasons for joining are not fully clear. Some say he feared that divisions among Franco's supporters could lead to losing the war. Others believe he was never a true Carlist but more of a conservative monarchist. Some scholars think he was a realist who understood that Carlism couldn't take power alone and needed allies. He might have thought the new system was mostly in line with Carlist ideas and wasn't worth fighting against. Finally, some believe he didn't fully understand how serious the situation was or the totalitarian nature of the new party. He might have thought it would be a loose alliance where Carlism could keep its identity.

In Franco's Government

In January 1938, Tomás became the Minister of Justice in Franco's first official government. In this role, he began to cancel the laws passed by the Second Spanish Republic, especially those that separated the Church and state. He made sure the Church regained a key role in areas like education.

He is also remembered for his part in the Francoist repressions. These were harsh actions taken against those who opposed Franco. While many executions happened before he took office, Tomás helped set up the repressive legal system of Franco's regime. This included large purges in the justice system. One important law, the Law of Political Responsibilities, was passed in 1939. This law made people responsible for political actions going back to 1934. Another law required all adults to have a personal ID card for the first time in Spanish history. When he left office in August 1939, there were about 100,000 political prisoners. It's not clear why he left his position.

It's not known if his departure from the government was due to tension between the Falangists and Carlists, though he didn't get along well with Ramón Serrano Suñer, Franco's brother-in-law. Serrano Suñer described Tomás as loyal to his traditions but more practical than truly believing in them. They disagreed especially on centralizing power versus regional rights.

By early 1938, Tomás was disappointed with the new party. In April 1938, he complained to Franco about Carlism being pushed aside. Franco told him that while he valued the Carlists, they were "few and not attractive to the masses," while the Falange could attract many people. Tomás admitted that he felt "a certain sadness for the disappointment and deception" about how things were turning out.

In 1939, he moved back to Navarre. Even though he was expelled from the Carlist movement, he still participated in Carlist events. Some people saw him as the leader of the "Rodeznistas," a group of Carlists who worked with Franco's government. He tried to support Carlist cultural groups. In 1940, he was elected vice-president of the Navarrese Provincial Council. In this role, he fought against the Falangists for power in the province. Thanks to his efforts, Navarre and Álava were the only provinces that kept some of their regional self-governance.

Even though he seemed overwhelmed by the new regime's nature, Tomás continued to work with the government. In 1943, he resigned from the Navarrese government to join Franco's parliament, the Cortes Españolas. He was a member of the National Council. His term lasted three years and was not renewed in 1946, suggesting he was no longer part of the Falangist leadership.

Supporting Don Juan

As early as the 1910s, Tomás had quietly suggested that if the Carlist royal line ended, the rights to the throne could go to a suitable candidate from the other branch of the Bourbon family, the Alfonsists. In 1935, he even proposed that the last direct Carlist claimant, Don Alfonso Carlos, name Don Juan (the son of the former King Alfonso XIII) as his heir.

When the last direct Carlist claimant died in September 1936, Tomás was slow to accept Don Javier as the regent. At that time, he was already thinking about Franco acting as regent for Don Juan, whom he believed understood Carlist ideas. Tomás and Don Juan started exchanging friendly letters in 1937.

In the early 1940s, Tomás openly supported Don Juan as a future Carlist king, especially after Don Juan inherited the Alfonsist title in 1941. In April 1945, Tomás traveled to Portugal to meet Don Juan. He wanted to prepare the way for Don Juan to be accepted by the Carlists. This led to an important document in February 1946, which Tomás helped write. This document, known as the "Bases de Estoril," outlined the basic principles of a future monarchy. It was very similar to Carlist ideas, though it didn't officially declare Don Juan the legitimate Carlist claimant.

The 1946 "Bases de Estoril" was Tomás's last major political effort. Not much is known about his political views or public activities in his final years. He remained a leader of the informal group of Carlists who worked with Franco and supported Don Juan. Even after Tomás's death, many Carlist leaders continued to support the idea of Don Juan becoming the Carlist king. In 1957, about 70 Carlist politicians traveled to Estoril and declared Don Juan the legitimate Carlist heir. Tomás was seen as the main person who promoted this idea.

See also

In Spanish: Tomás Domínguez Arévalo para niños

In Spanish: Tomás Domínguez Arévalo para niños

- Carlism

- Francoist Spain

- Spanish Civil War

- Count of Rodezno

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |