Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Prince Xavier |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duke of Parma | |||||

|

|||||

| Head of the House of Bourbon-Parma | |||||

| Tenure | 15 November 1974 – 7 May 1977 | ||||

| Predecessor | Duke Robert Hugo | ||||

| Successor | Duke Carlos Hugo | ||||

| Born | 25 May 1889 Villa Pianore, Lucca, Kingdom of Italy |

||||

| Died | 7 May 1977 (aged 87) Zizers, Switzerland |

||||

| Burial | Solesmes Abbey | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Princess Marie Françoise, Princess of Lobkowicz Prince Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma and Piacenza Princess Marie Thérèse Princess Cécile Marie, Countess of Poblet Princess Marie des Neiges, Countess of Castillo de la Mota Prince Sixtus Henry, Duke of Aranjuez |

||||

|

|||||

| House | Bourbon-Parma | ||||

| Father | Robert I, Duke of Parma | ||||

| Mother | Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

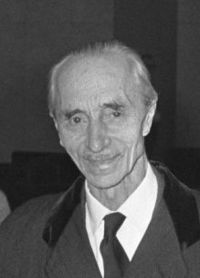

Prince Xavier (born May 25, 1889 – died May 7, 1977) was an important figure in European history. He was the leader of the Bourbon-Parma family. He also claimed to be the King of Spain for a group called the Carlists. In France, he was known as Prince Xavier de Bourbon-Parme. In Spain, people called him Francisco Javier de Borbón-Parma or simply Don Javier.

He was the second son of Robert I, who used to be the Duke of Parma. His mother was Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal. Xavier grew up in France, Italy, and Austria, where his family owned many properties. He went to a strict school called Stella Matutina.

During World War I, Prince Xavier joined the Belgian army and fought bravely. He and his brother Sixtus helped in a secret plan called the Sixtus Affair. This plan was an attempt by their brother-in-law, Emperor Charles I of Austria, to make peace with the Allies. The plan did not work out.

In 1936, a Carlist leader named Don Alfonso Carlos died without children. He chose Xavier to be the new leader of the Carlists. Xavier became the regent, meaning he would rule until a new king was chosen.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), Xavier supported the Carlist troops, known as Requetés. They fought alongside General Franco's side. Xavier visited the front lines but was sent out of Spain in 1938. He then lived in France.

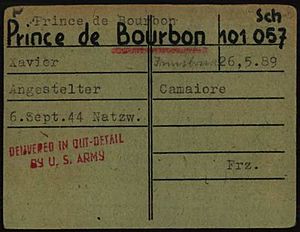

When World War II began, he joined the Belgian army again. After the Nazis invaded Belgium and France, he became part of the French Resistance. In 1941, the Gestapo arrested him. He was sentenced to death but was later sent to different prisons. In September, he was sent to Dachau and was freed by American soldiers in April 1945.

In the 1950s and 1960s, he was very active in the Carlist movement. In 1952, he was declared King of Spain in Barcelona, taking the name Javier I. Soon after, Franco's government expelled him from Spain. In 1974, he became the Duke of Parma after his nephew Robert died. By then, he was not well due to a car accident in 1972. He gave his political power to his oldest son, Prince Carlos Hugo, and officially stepped down as Carlist king in 1975.

Contents

Prince Xavier's Early Life

His Family Background

Xavier was born into the very important Bourbon-Parma family. This family was a branch of the Spanish Bourbons, who were related to the French Bourbons. Xavier was a descendant of King Louis XIV of France and King Felipe V of Spain.

Many of his relatives were kings, queens, or dukes in Europe. His father, Robert I, was the last ruling Duke of Parma. His mother, Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal, was the daughter of a deposed king of Portugal.

Xavier had many aunts and uncles from royal families. His aunt, Maria Ana of Portugal, was the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg. His sister Zita became the Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary. His brother Felix became the Duke-consort of Luxembourg.

Growing Up and Education

Even though his father was no longer the Duke of Parma, the family was very wealthy. They owned large estates in Italy and Austria, and the famous Chambord castle in France. The family, with about 20 children, lived in two main homes. They moved between them every six months, even taking their horses on a special train.

Xavier's childhood was happy and luxurious. The family was very Catholic and spoke mostly French and German. Xavier also learned Italian, English, Portuguese, Spanish, and Latin. Many important people from noble families and universities visited them.

In 1899, Xavier went to Stella Matutina, a famous Jesuit school in Austria. The school was strict, but it taught high standards and a humble religious life. Xavier joked that the school prepared him for the Nazi concentration camp. He graduated in the mid-1900s.

In 1906, he moved to Paris for university. He studied political-economic sciences and agronomy (the science of soil management and crop production). He finished both degrees, becoming an engineer in agronomy and a doctor in politics/economy. He never started a regular job.

In 1910, his father's wealth was divided among the family. Xavier received money and some smaller properties. He lived in Paris but traveled a lot. He went to Austria for his sister's wedding to the heir of the Austro-Hungarian throne. He also traveled to Spain and Portugal.

Xavier loved exploring, like his brother Sixtus. In 1909, they traveled to the Balkans. In 1912, they explored Egypt, Palestine, and the Near East. In 1914, they planned a trip to Persia and India.

Soldier and Diplomat During World War I

When Archduke Franz Ferdinand was killed in 1914, Xavier and Sixtus were in Austria. They wanted to join the Austrian army. But when France declared war on Austria, they decided to fight for France instead. They were French at heart.

French law did not allow members of foreign royal families to serve in their army. So, they asked their cousin, Queen Elisabeth of Belgium, for help. She arranged for them to join the Belgian army. In late November 1914, Xavier joined as a private in the medical services. He later became a captain.

In late 1916, Xavier became involved in the Sixtus Affair. This was a secret attempt by the new Austrian Emperor, Karl I, to make a separate peace. Karl I used his family ties with the Bourbon-Parma brothers for this mission. Xavier's role was less important than his brother Sixtus's. However, he was present at key meetings in Paris, Switzerland, and Vienna.

The peace talks failed in early 1917. The secret was leaked in 1918, causing a scandal that hurt the Emperor's reputation. Xavier and Sixtus were in Vienna at the time and were in danger. The incident is seen as an example of amateur diplomacy. Xavier was a major in the Belgian army by the end of the war. He received several awards for his service.

Marriage and Family Life

After the war, Xavier helped his sister Zita and her husband Karl after they lost their thrones. He also focused on his own financial situation. He and his brother Sixtus sued the French state over the Chambord castle. The court cases lasted for years, but they eventually lost.

In his mid-30s, Xavier met Madeleine de Bourbon-Busset, who was nine years younger. She came from a branch of the French Bourbons. The head of Xavier's family, his half-brother Élie, said their marriage would not be considered royal. Despite this, Xavier married Madeleine in 1927. Some newspapers still called her "princess."

Madeleine was wealthy, so the marriage improved Xavier's financial status. They settled at Bostz castle, where Xavier managed her family's farms. Their first child was born in 1928, and they had five more children throughout the 1930s. After his father-in-law died in 1932, Xavier took over the family business. This was a happy time for him. However, his close friend and mentor, his brother Sixtus, died in 1934, which was a sad event.

Becoming Don Javier

Before the mid-1930s, Xavier did not openly take part in politics. However, he was involved in some French royalist groups. Some of his relatives were involved in politics to restore royal families. Others were more liberal.

Xavier did not show much interest in Spanish politics at first. But this changed when Jaime III died in 1931. Alfonso Carlos I became the new Carlist claimant to the Spanish throne. Alfonso Carlos was old and had no children. He was related to the Bourbon-Parmas and had close ties with them.

Alfonso Carlos knew the Carlist royal line would end with him. He considered uniting with another branch of the Bourbons. He also thought about who would lead the Carlists after him. After Sixtus died in 1934, Xavier became the most senior Bourbon-Parma relative to Alfonso Carlos. They discussed the future of the Carlists.

Alfonso Carlos chose Xavier to be the regent. A regent rules for a king who is too young or absent. Scholars believe Xavier was chosen because he was a strong believer in royal rights, a good Christian, humble, and fair. Xavier probably accepted because he felt it was his family and Christian duty. He thought his regency would be short, just a few months, until a new Carlist king could be chosen. This was announced in April 1936.

Regent of the Carlists

Leading During the Spanish Civil War

In February 1936, elections in Spain led to a new government, and the country became very unstable. The Carlists started planning their own uprising. They also talked with military leaders who were planning a coup. Prince Xavier, now known as Don Javier in Spain, set up his base in France. From June to July, he met with Carlist politicians.

Don Javier insisted that the Carlists should only join the military coup if they had a clear political agreement first. However, the Carlists ended up joining the coup on unclear terms. Their main hope, General Sanjurjo, who had promised to support Carlist interests, died.

Sanjurjo's death was a big blow to the Carlists. Power went to other generals who did not care about the Carlist cause. Don Javier, watching from France, oversaw the Carlist military efforts. But he could not talk directly with the generals. When Alfonso Carlos died on October 1, Don Javier was officially declared the regent. He was now leading the movement during a time of great chaos.

He was not allowed into Spain. He wrote protests about how the Carlists were being pushed aside by Franco's side. In early 1937, he faced pressure to merge the Carlist group into a new state party. He wanted to resist this. After the Unification Decree in May, he entered Spain. He wore a requeté general's uniform, challenging Franco. He visited the front lines to boost Carlist morale. A week later, he was expelled from Spain.

After another short visit and expulsion in late 1937, Don Javier tried to protect the Carlist identity. He did not want to completely break ties with Franco's government. He allowed some trusted Carlists to join Franco's party, but he expelled those who joined without his permission. With the Carlist leader in Spain, Manuel Fal Conde, Don Javier managed to prevent the Carlists from being fully absorbed into the state party.

However, Don Javier could not stop the Carlists from being pushed aside. Their newspapers and groups were shut down. In 1939, he offered a plan to Franco. It suggested restoring the traditional monarchy with a temporary group of regents, possibly including Don Javier and Franco. But Franco did not follow up on this idea.

Prisoner During World War II

When World War II started, Prince Xavier rejoined the Belgian Army as a major. The Germans quickly advanced, pushing the Belgians back. Xavier's unit was forced into Dunkerque. During the chaos, the Belgians could not get on the British evacuation ships. Don Javier became a German POW.

He was released quickly and returned to his family castles in France. His properties were split by the demarcation line: one in the German-occupied zone and one in the Vichy zone.

In the early 1940s, Prince Xavier became more isolated from Spanish affairs. He and the Spanish Carlists could not cross the border. Their letters were censored. He sent documents, like the Manifiesto de Santiago (1941), urging Carlists to remain loyal but not openly rebel against Franco. With Don Javier and Fal Conde often unable to communicate, the Carlist movement became confused.

From 1941 to 1943, Prince Xavier lived quietly with his family. He managed the Bourbon-Parma family's wealth. He became more against the Pétain government in France. He secretly helped Resistance leaders. He even helped people hiding from forced labor camps on his estates. He provided them with food and shelter.

When two people he was helping were caught, Prince Xavier rode his bicycle to Vichy and successfully got them released. This put him in danger. In July, the Gestapo arrested him. He was sentenced to death for spying and terrorism. However, Pétain pardoned him. He was held in several prisons before being sent to Dachau in September. The Nazis asked Franco about him, but Franco said he didn't care. Xavier was often put in a starvation cell. When American soldiers freed him in April 1945, he weighed only 36 kg (about 79 pounds).

After the War: Rebuilding Carlism

After recovering his health, Prince Xavier testified at Pétain's trial in 1945. His testimony was mostly positive for Pétain. In December, he secretly entered Spain for a few days. He met with Carlist leaders in San Sebastián. They agreed to reorganize the Carlist movement. Don Javier confirmed Fal Conde's authority. He also stuck to a strict political line. This meant not working with Franco's government but also not openly rebelling. It also meant not negotiating with the Alfonsine branch of the Bourbons.

In the late 1940s, Don Javier and Fal Conde's policies faced challenges within the Carlist movement. Some Carlists wanted Don Javier to declare himself king right away. They thought he was delaying to get the crown for his family by being too soft on Franco. They were angry about his unclear stance on Franco's proposed law about succession. Others were tired of the strict approach and wanted more flexibility. Especially after news in 1949 about Franco talking with Don Juan, Don Javier was pressured to be more active.

Don Javier and Fal Conde kept strict control. They removed some leaders who disagreed with them. But they also tried to make Carlism stronger. They allowed Carlists to take part in local elections and tried to create student and worker groups. However, Fal Conde also started to believe that the regency was a problem. Most people wanted Don Javier to become king himself.

In 1952, Don Javier decided to give in to the pressure. During a Catholic event in Barcelona, he issued documents. These documents hinted that he was taking on royal rights, but they were vague. He did not clearly say he was king.

Becoming King Javier I

A King, But Not Really?

Carlist leaders were excited. They spread the news that the regency was over and King Javier I was ruling. Carlists everywhere were thrilled. However, the very next day, Don Javier made comments that cast doubt on this. When asked by the Minister of Justice, he said he had not signed any document and had not proclaimed himself king.

Franco's government did not believe him. Don Javier was quickly expelled from Spain. In 1953–1954, Carlist leaders boasted of their new king, but Don Javier stayed at his castle in France. He reduced his political activity. In private, he downplayed the "Acto de Barcelona," calling it "a very small ceremony."

Carlist members who disagreed with him started speaking up again. Don Javier seemed tired of his role. He even considered making a deal with Don Juan, another claimant to the throne. In early 1955, he visited Spain and made some unclear comments. He called the 1952 statement "a grave error" and said he had been forced into it. This caused a major disagreement between him and Fal Conde, who resigned. Don Javier replaced him with a group of leaders.

In late 1955, Don Javier issued a statement saying Carlists were "guardians of heritage" rather than a political party seeking power. He privately thought his claim to the throne was stopping an alliance of all reasonable people. The year 1956 was confusing, with many conflicting statements. Another incident led to Don Javier being expelled from Spain again.

The situation changed with the rise of a new force. Young Carlists, unhappy with Don Javier's indecision, turned to his oldest son, Hugues. Hugues, who was studying economics in Oxford, agreed to get involved in Spanish politics. Don Javier allowed him to appear at the annual Montejurra gathering in 1957. There, Hugues referred to "my father, the king."

Hugues knew little about Carlism and barely spoke Spanish. It seems Don Javier had not planned for him to be his successor. He probably wanted to free himself and his family from the Carlist burden. It is unclear what he thought about his son's sudden involvement. Perhaps he felt relieved to have found someone to help or replace him. Many people felt that he "had stopped being indecisive."

A More Active King

Under the leadership of José María Valiente, and with Don Javier's permission, the Carlist leaders began to work cautiously with Franco's government. Hugues was presented as representing a new strategy. Some believe Don Javier saw his son's involvement as a chance for long-term gains. He hoped Franco's government might one day crown his son. Others think the political changes and Hugues's coming of age simply happened at the same time.

From 1957 onwards, Don Javier slowly allowed his son to take a bigger role in Carlism. In the late 1950s, Don Javier stopped all talks of uniting with the Alfonsinos. He ordered strong actions against anyone who approached them. However, he still respected Don Juan and avoided open challenges. He also did not explicitly claim the title of king himself.

He supported Valiente in trying to stop internal rebellions against working with the government. He also fought against new groups that wanted to break away. Twenty years earlier, he had expelled Carlists who joined Franco's groups. But in the early 1960s, Don Javier saw the appointment of five Carlists to the Cortes (Spanish parliament) as a success. This was because Franco's government allowed new Carlist legal groups. The movement could openly take part in public discussions.

Another important step came in 1961–62. Don Javier symbolically declared Hugues "Duque de San Jaime," a historic title. He then told his followers to see Hugues as "a king." Hugues legally changed his name to "Carlos Hugo." He moved to Madrid and set up his own advisory group. For the first time, a Carlist heir lived in the capital and openly pursued his own politics. From this point, Don Javier was seen as giving daily tasks to his son. He only provided general guidance from the background.

Carlos Hugo slowly took control of communication with his father. He also became the main representative of the Bourbon-Parma family in Spain. Don Javier's three daughters, all in their 20s, also helped their brother. They worked to improve his image with the Spanish public. Don Javier's younger son, Sixte, soon followed their example.

The King and His Son

Carlos Hugo and his helpers started an active policy. They launched new ideas and made sure the young prince was recognized in the national media. Politically, they began to promote new theories. These ideas focused on society as the goal of politics. At first, their strategy was to appeal to the socially-minded, strong Falangists. Later, it became more like Marxist ideas.

Traditional Carlists became worried about Carlos Hugo's political moves. They tried to warn Don Javier. However, Don Javier repeatedly assured them that he fully trusted Carlos Hugo. In 1967, Don Javier confirmed that the Carlist beliefs of "God, Homeland, Rights, King" were still important. But he also said that new times needed new practical ideas. He approved changes in the Carlist organization. By the mid-1960s, Don Javier allowed Carlos Hugo and his supporters to control the Carlist movement. In 1965, Don Javier explicitly called himself "king" for the first time. He continued to use this title from then on.

Some writers say that Don Javier fully knew about and supported Carlos Hugo's changes to Carlism. They believe these changes were meant to update Carlist ideas and remove old distortions.

Other scholars argue that the aging Don Javier, who was in his late 70s, was increasingly out of touch with Spanish issues. They believe he was unaware of the political direction Carlos Hugo was taking. They suggest that his son and two daughters might have manipulated him. They might have intercepted his mail and changed his outgoing messages.

As late as 1966, Don Javier continued to try to work with Franco. But the years 1967–1969 changed his relationship with Carlism and Spain. In 1967, he accepted Valiente's resignation. Valiente was the last traditional Carlist leader in the executive. Don Javier gave political leadership to groups controlled by Carlos Hugo's supporters. This marked their final victory in controlling the organization.

In 1968, Carlos Hugo was expelled from Spain. To show support, Don Javier flew to Madrid a few days later. He was quickly expelled for the fifth time. This event marked the end of their difficult talks with Franco's government. The Carlists then shifted to being completely against the government.

In 1969, the Alfonsist prince Juan Carlos de Borbón was officially named as Franco's future king. This ceremony crushed the Bourbon-Parmas' hopes for the crown. When Franco died in 1975, Juan Carlos did indeed become King of Spain.

Later Years and Abdication

Don Javier mostly lived at Lignières. He withdrew from public life, only occasionally issuing statements that his son read at Carlist gatherings.

In 1972, Don Javier was seriously injured in a car accident. He formally gave all his political power to Carlos Hugo. In 1974, after his half-nephew Prince Robert, Duke of Parma died without children, Don Javier became the head of the Bourbon-Parma family and took the title of Duke of Parma.

He could now enjoy family life. His two older children had married and had eight grandchildren. However, family relationships became tense due to politics. Carlos Hugo, Marie-Thérèse, Cécile, and Marie des Neiges supported a progressive agenda. But his oldest daughter Françoise Marie, youngest son Sixte, and their mother Madeleine opposed this. Sixte, known as Don Sixto in Spain, openly challenged his brother. He declared himself the leader of Traditionalism and started his own group.

In 1975, Don Javier stepped down as the Carlist king in favor of Carlos Hugo. Some sources say he expelled Sixto from Carlism for not recognizing this decision. It is not clear what he thought about the start of Spain's move to democracy. After the 1976 Montejurra events, he mourned the dead. He officially disowned Don Sixto's political views and called for Carlist unity. However, in a private letter, Don Javier said that at Montejurra, "the Carlists have confronted the revolutionaries." This has been seen as meaning that Don Sixto's followers were the true Carlists in Don Javier's eyes.

Early March 1977 was a difficult time. On March 4, he was interviewed by the Spanish press with his son Sixto. His answers showed traditional Carlist views. That same day, he signed a statement saying his name should not be used to support a "grave doctrinal error within Carlism." This was a clear rejection of Carlos Hugo's political line. Carlos Hugo then told the police that Sixto had kidnapped his father. Don Javier publicly denied this, but the scandal made him very ill.

Soon after, Don Javier signed another statement, confirming Carlos Hugo as his "only political successor and head of Carlism." Then, his wife, Doña Madalena, said that Carlos Hugo had taken her husband from the hospital against medical advice and his will. She claimed Carlos Hugo had threatened his father to get him to sign the second statement. Don Javier was then moved to Switzerland, where he died soon after. His widow blamed Carlos Hugo and his three daughters for his death.

Children

- Princess Marie Françoise of Bourbon-Parma, born August 19, 1928. She married Prince Edouard de Lobkowicz (1926–2010) and had children.

- Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma, born April 8, 1930 – died August 18, 2010. He married Princess Irene of the Netherlands (born 1939) and had children.

- Princess Marie Thérèse of Bourbon-Parma, born July 28, 1933 – died March 26, 2020. She was a victim of COVID-19.

- Princess Cécile Marie of Bourbon-Parma, born April 12, 1935 – died September 1, 2021.

- Princess Marie des Neiges of Bourbon-Parma, born April 29, 1937.

- Prince Sixtus Henry of Bourbon-Parma, born July 22, 1940.

In Fiction

The TV show The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles features Xavier (played by Matthew Wait) and his brother Sixtus (played by Benedict Taylor). They are shown as Belgian officers in World War I who help the young Indiana Jones.

Writings

- La République de tout le monde, Paris: Amicitia, 1946

- Les accords secrets franco-anglais de décembre 1940, Paris: Plon, 1949.

- Les chevaliers du Saint-Sépulcre, Paris: A. Fayard, 1957.

Honours

Calabrian House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies Knight Grand Cross of Justice of the Calabrian Two Sicilian Order of Saint George

Calabrian House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies Knight Grand Cross of Justice of the Calabrian Two Sicilian Order of Saint George Belgium: Knight Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold

Belgium: Knight Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold Belgium: Croix de Guerre

Belgium: Croix de Guerre France: Croix de Guerre

France: Croix de Guerre : Sovereign Knight of the Order of Prohibited Legitimacy

: Sovereign Knight of the Order of Prohibited Legitimacy

See also

In Spanish: Javier de Borbón-Parma para niños

In Spanish: Javier de Borbón-Parma para niños

- Carlism

- Traditionalism (Spain)

- House of Bourbon-Parma

- Robert I of Parma

- Prince Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma

- Prince Sixtus Henry of Bourbon-Parma

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |