Manuel Fal Conde facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Manuel Fal Conde

|

|

|---|---|

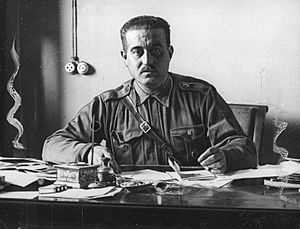

Fal Conde in Toledo, 1936

|

|

| Born |

Manuel Fal Conde

10 August 1894 |

| Died | 20 May 1975 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for | Political leadership |

| Political party | Carlism |

Manuel Fal Conde, 1st Duke of Quintillo (1894–1975) was a Spanish Catholic leader and a Carlist politician. He is known as a very important person in the history of Carlism. He was its main political leader for over 20 years, from 1934 to 1955. He guided the movement during a very difficult time in Spain. At first, he led a group that wanted to fight against the government. During the Spanish Civil War, he joined the Nationalists. Later, he opposed the government of Francisco Franco.

Contents

Manuel Fal Conde's Early Life

Manuel Fal Conde came from an important family from Asturias, a region in Spain. His family later settled in Higuera de la Sierra, a small town in southern Spain. His father, Domingo Fal Sánchez, was an eye doctor and also ran a small business. He was even the mayor of Higuera for a few years.

Manuel's mother, María Josefa Conde, died shortly after he was born. His father's sister helped raise Manuel and his three older siblings. They grew up in a very religious Catholic home.

Manuel's Education and Studies

Manuel started school at a Jesuit college in Villafranca de los Barros. This Jesuit education was very important for him. One of his teachers, Gabino Márquez, saw that Manuel was a very promising student.

After finishing high school in 1911, Manuel thought about becoming a Jesuit priest. Then he considered studying medicine. But his father encouraged him to study law instead, as his older brother was already studying medicine. So, Manuel began studying law in Seville.

At the University of Seville, Manuel joined a group led by Manuel Sanchez de Castro. This professor was a Carlist and a strong supporter of Catholic ideas in Seville. Manuel finished his law degree in 1916. After a year in Madrid, he earned his doctorate.

In 1918, he became a lawyer in Seville and opened his own office. He also taught history, law, and ethics at a Jesuit college. He even did research on Spanish political law at the university.

His Family Life

In 1922, Manuel Fal Conde married María de los Reyes Macias Aguilar. They had seven children together. Some of their children later became active in the Carlist movement. They opposed the changes happening in the Carlist party in the 1970s.

Starting in Politics

It is not clear if Manuel Fal Conde's family had been Carlists for a long time. But his father was a very religious Catholic. Manuel's strong Catholic beliefs and traditional views were likely shaped by his Jesuit education. The Jesuits at that time supported a very traditional and religious view of society.

Manuel started his public work during his university years in Seville. He joined a student group and soon became its president. This group focused on Catholic social and political ideas. In the 1920s, he became very active in many Catholic organizations. These included groups for education, charity, and even trade unions. He also started some of his own projects. All this work showed that Manuel was a great organizer.

He also wrote for Catholic newspapers. He even launched his own daily newspaper later on. This shows he was good at journalism.

Joining the Carlist Movement

Manuel Fal Conde believed that politics was a Christian duty. He first became involved in politics in 1930. He helped organize the Traditionalist-Integrist Party in Seville and became its leader there.

When the Second Spanish Republic was declared in 1931, Manuel was very worried. He personally tried to protect churches in Seville from violence that broke out in May 1931. In June 1931, he ran for a seat in the Spanish parliament, but he did not win. After that, he focused on his newspaper, El Observador, which became a very conservative Catholic newspaper in Seville.

In 1932, the Integrists joined with the Carlists to form Comunión Tradicionalista. Fal Conde was put in charge of the Carlist group in West Andalusia. He did a great job of making Carlism popular in areas where it hadn't been before. He was very open about his dislike for the new Republic.

Fal Conde was arrested for three months after a failed military uprising in 1932. But this did not stop him. He continued to talk to military leaders about a possible Carlist uprising. He also started a youth movement for Carlism and a successful Workers Section in Andalusia.

Leading the Carlists

Fal Conde became well-known across Spain. In November 1933, the Carlist leader, Alfonso Carlos, made Fal Conde the regional leader for all of Andalusia.

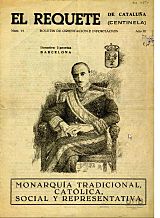

In April 1934, the Carlists organized a huge meeting at the Quintillo estate near Seville. This event showed how strong the Carlists were in the region. A parade of 650 uniformed and trained Carlist soldiers, called Requetés, made a big impression.

Because of his excellent organizing skills, Fal Conde became a top choice to lead the national Carlist movement. In May 1934, even though he was relatively young, he was named Secretary General of the Comunión. People called him the "Sevillian Zumalacárregui" (a famous Carlist general).

Reorganizing the Carlist Party

Fal Conde began a huge effort to reorganize the Carlist party. He created new central offices and councils. He also launched an official Carlist newspaper to improve communication. Most importantly, he brought all the different Carlist groups, like the Requeté and the youth groups, under central control.

New groups were created, such as the Agrupación Gremial for city workers and Socorro Blanco, a Carlist Red Cross organization. A group for younger boys, called Pelayos, was also started. The party also began collecting internal taxes. Carlist newspapers were coordinated to spread their message more effectively.

These changes made the Carlist party much stronger and more organized. It helped the party grow rapidly. Carlism started to expand into new areas and attract different kinds of people, including city workers.

Fal Conde believed that Carlism should not rely on alliances with other political groups. He wanted the Carlists to be in control. He did join a group called the National Bloc in late 1934, but he made sure it was not a strong commitment. He later left this alliance in 1936. He also did not trust another big right-wing party, CEDA.

Under Fal Conde, the Carlists focused less on elections and more on building up their organization, especially their military wing. He believed that the Republic needed to be overthrown by force. Starting in 1935, Carlist rallies used strong language about fighting and sacrifice.

Even though some older Carlist leaders thought he was just a boring manager, Fal Conde was greatly admired by the Requeté and the youth. In December 1935, the Carlist king, Alfonso Carlos, promoted Fal Conde to a higher leadership role.

During the Civil War

Fal Conde was convinced that the Carlists needed to act first against the democracy. He started preparing for war. His first plan was for a Carlist uprising with some help from the army. He wanted General Sanjurjo to lead it.

However, other generals, like Mola, did not agree to Fal Conde's conditions. These conditions aimed to replace the Republic with a Traditionalist monarchy. Instead, Mola started talking to Carlist leaders in Navarre, who were willing to join a rebellion without many conditions. Fal Conde was outmaneuvered, but he decided not to cause an open conflict.

When the Civil War began, Fal Conde led the new Carlist wartime group. But he soon realized that Carlism was becoming a junior partner to the military, not an equal one. The death of General Sanjurjo, his key ally, weakened his position. Also, the death of the Carlist king, Alfonso Carlos, left the movement without a clear leader.

The Carlist units, the Requetés, were put under the generals' command and spread out across different fronts. This meant Carlism was indeed being controlled by its allies, just as Fal Conde had feared.

Challenges and Exile

To make the Carlist position stronger against the military, Fal Conde started two new projects in November 1936. One was a general labor organization. The other was a Military Academy to train Carlist commanders.

Franco, the leader of the Nationalists, did not like Fal Conde's independent actions. In December, Franco told Fal Conde he had to choose between going into exile or facing a firing squad. Fal Conde left Spain for Lisbon, Portugal. He remained the official, though distant, Carlist leader.

Franco wanted to unite all the different right-wing groups, including the Carlists, into one party. Fal Conde believed that any unification should be on Carlist terms. But other Carlist leaders, especially those from Navarre, were ready to accept Franco's terms.

After Franco issued the Unification Decree in 1937, Fal Conde was no longer the official leader of the Carlists. At first, he did not protest and even advised others to obey. Franco offered him a job in the new government, but Fal Conde refused. His exile ended in October 1937. He then advised the Carlist regent, Don Javier, to expel anyone who joined Franco's new party. This meant that the unification became more about Franco's party absorbing parts of the Carlist movement.

Life Under Franco

When Fal Conde returned from exile, he was watched by security forces. He tried to stop Franco's new party from taking over Carlist property, but he was mostly unsuccessful. He tried to rebuild the Carlist party by communicating with loyal leaders.

In March 1939, Fal Conde sent a letter to Franco. He respectfully argued that Franco's new government would not last. He suggested that a traditional monarchy should be restored, perhaps with Franco as part of a temporary leadership. Some historians see this letter as a sign that Fal Conde was now completely against Franco's government.

Franco did not respond to the letter. However, after Fal Conde appeared on a balcony in Pamplona in October 1939, causing a disturbance, he was placed under house arrest in Seville.

From his house arrest, Fal Conde led the strongest Carlist opposition to Franco's rule. He believed no Carlist should work with Franco's government. He tried to rebuild Carlist groups, often disguised as religious or veteran activities. He also started a hidden Carlist education network.

Fal Conde told Carlists not to join the Spanish volunteers fighting with Germany in World War II. He believed Spain should stay neutral. Despite this, he was accused of being involved in a British plot and was exiled to Ferreries for four months in 1941.

After returning to Seville, Fal Conde was sometimes allowed to travel. He attended large Carlist gatherings in 1942 and 1945. In 1943, he helped create another letter to Franco, which also went unanswered. In August 1945, Fal Conde wrote a personal letter to Franco, asking to be released from house arrest. He was released in November 1945, after six years. During this time, he continued to work as a lawyer.

Later Years and Legacy

In December 1945, there were Carlist protests in Valencia and Pamplona. Some people think these were planned as a revolt against Franco. Fal Conde then met with Don Javier, the Carlist regent. He also wrote to Don Juan, inviting him to recognize Don Javier's regency.

Fal Conde began visiting Carlist groups across Spain. In 1947, he gathered 48 local Carlist leaders in Madrid. This meeting re-established the Carlist national council. A document released afterwards confirmed that the Carlists would not work with Franco's government or other monarchist groups. A large Carlist gathering in Montserrat in 1947 showed that the movement was getting stronger again.

However, Fal Conde's leadership faced criticism from two groups. Some Carlists, called the Sivattistas, thought he was trying to make Don Javier the king by pleasing Franco. They were angry when Fal Conde suggested supporting Franco's law on succession in a referendum, seeing it as helping the regime. They wanted a new Carlist king to be declared right away.

On the other hand, some Carlists were tired of Fal Conde's strict opposition to Franco. They wanted a more flexible approach and more legal ways to act.

Fal Conde tried to deal with these challenges. He allowed individual Carlists to run in local elections to gain more influence. In 1951, he started a campaign to buy a national newspaper, Informaciones, which became an unofficial Carlist platform. Student and worker groups also became more active.

In 1952, during a big Catholic event in Barcelona, Don Javier claimed his rights as king. He was quickly expelled from Spain by Franco's government.

As Don Javier later stepped back from this claim and Franco's government remained strong, Fal Conde's policy of strict opposition seemed to be a dead end. Some Carlists wanted a stronger anti-Franco stance, while others wanted to work with the regime. Many also complained about Fal Conde's "authoritarian style."

Fal Conde himself was getting tired. In July 1955, he wrote to Franco, seeming to accept that Carlism might just have to survive. Even though he and Don Javier had always agreed, Don Javier also felt that Carlism needed a new leader. In August 1955, Fal Conde resigned as the main Carlist leader.

Retirement and Final Years

After resigning, Fal Conde stepped back from daily politics. He remained loyal to the new Carlist leader, Valiente, even though Valiente adopted a new strategy of working with Franco's government. Fal Conde continued to oppose Franco, but he avoided extreme actions.

In 1967, Don Javier made Fal Conde the Duke of Quintillo, a very special honor. It was the only time Don Javier gave a noble title to someone outside the royal family. However, their relationship became strained. Fal Conde did not attend the ceremony due to health reasons.

Don Javier and his son, Carlos Hugo, asked Fal Conde to support a new law by Franco in a 1966 referendum. Fal Conde agreed to recommend participation, but he refused to endorse the law because he was still against Franco.

When the Borbón-Parmas were expelled from Spain in 1968, Fal Conde refused their requests to meet Franco to reverse the decision. He said he had no reason to visit the dictator as a penitent. He also expressed concern about Carlos Hugo's move towards socialist ideas in the late 1960s.

Despite his doubts, Fal Conde did not join those who turned against the Carlist dynasty. By 1973, he felt loyal to Don Javier as king, but disagreed with his political direction. In 1974, Fal Conde lost all hope about the Borbón-Parmas' shift to the Left.

Throughout his life, Fal Conde was a very devoted Catholic. He received communion every day, even during the Civil War. After he retired from politics, he spent even more time on religious matters. He helped found religious groups and was active in Catholic initiatives in Andalusia. He also led a Catholic publishing house.

In his final years, "Don Manuel" was seen as a respected elder in Andalusian Catholicism and among traditional Carlists across Spain. He remained emotionally close to Don Javier. Manuel Fal Conde died in 1975, one month after Don Javier gave up his claim to the Carlist throne.

See also

In Spanish: Manuel Fal Conde para niños

In Spanish: Manuel Fal Conde para niños

- Carlism

- Integrism (Spain)

- Don Javier

- Tomás Domínguez Arévalo

- Maurici de Sivatte i de Bobadilla

- Unification Decree (Spain, 1937)

Images for kids

-

Semana Santa, Seville, around 1915

-

The Republic declared in 1931.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |