Unification Decree (Spain, 1937) facts for kids

The Unification Decree was a big political decision made by Francisco Franco on April 19, 1937. At this time, Franco was the leader of Nationalist Spain during the Spanish Civil War. This decree combined two main political groups: the Falangists and the Carlists. They became one new party called the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS).

With this decree, all other political parties were banned. This meant FET y de las JONS was the only legal party in Nationalist Spain. It was meant to connect the government with the people. Franco himself became the leader of this new party. He had a special group of advisors to help him. This step helped Franco gain complete control over politics. It also brought a formal sense of unity to the Nationalist side. Many experts believe this was a move towards a state where the government had total control. This new, stronger Falange party was Spain's only legal party for the next 38 years. It became a key part of Franco's government.

Contents

Why the Unification Happened

When the military leaders started the war in 1936, they didn't have a clear plan for Spain's future government. At first, local groups were supposed to help run things. Most right-wing groups in Spain were not deeply involved in the initial plan. Only the Carlists made a deal with General Emilio Mola, a key leader. This deal was more about joining the fight than about how Spain would be governed later.

Early statements from the generals were not very clear about politics. In areas controlled by the rebels, local leaders appointed mayors. These leaders were often from groups like CEDA, Alfonsism, or Carlism. A group called the National Defense Junta was set up to manage the war, not to make political decisions. On July 30, they declared martial law, which meant no political activity was allowed. Later, they banned parties that were against their "patriotic movement." They said that in the future, there would be "only one politics."

This ban was not strictly enforced on right-wing groups. But their situations were very different. The largest group, CEDA, was falling apart. Its leader, José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones, stopped all CEDA political activity. Other groups like Renovación Española and Partido Agrario were also weakening.

However, two groups grew very fast: the Carlist Comunión Tradicionalista and the Falange Española de las JONS. The Carlists had their own war councils and volunteer fighters called Requetés. They had about 20,000 men. The Falange, which was very small before the war, grew hugely. It became the most active right-wing party. Its groups worked freely, and its militias quickly recruited 35,000 volunteers.

In October 1936, Francisco Franco took supreme power in the rebel zone. He set up a government called the Junta Técnica del Estado. The people he chose for this government were mostly traditional conservatives. Franco allowed some political talks but kept politicians under control. For example, CEDA leader Gil-Robles had to stay in Portugal. The Carlist leader, Manuel Fal Conde, was sent away from Spain. Military censors stopped any party propaganda that went too far. Franco met with right-wing politicians, but he usually ignored those who were too stubborn. He expected them to support his government without asking for political promises. He said that in the future, "the people" would decide Spain's government.

Falangists and Carlists: Two Strong Groups

A few months into the Civil War, it was clear that the power balance among right-wing parties had changed. The old parties like CEDA were now much smaller than the Carlists and Falange. These two groups provided about 80% of the volunteers for the Nationalist militias. Their ability to recruit was very important to Franco and the military.

Both groups saw themselves as future leaders of a new Spain. The Carlists believed they were the military's main political partners. They thought the Nationalist effort was a Carlist-military team-up. The Falangists saw the war as a syndicalist revolution. They believed Falange was the only true political force. Both the Carlists and Falange saw the army as a necessary tool to win the war. But they expected the army to stay out of politics. Each group claimed the right to decide Spain's future government.

The Falange was the most active political power. It started in 1933 as a small party known for street fights. But in 1936, it attracted thousands of young people. Its leader, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, and many other top members were stuck in the Republican zone. So, in September 1936, Falange formed a temporary leadership group. It was led by Manuel Hedilla. The party kept growing, creating youth, women's, and other sections. By late 1936, Falange supplied about 55% of all volunteers. It was clearly ahead of the Carlists. Franco met with Hedilla and listened to his advice. But he usually said no to Hedilla's requests. The Falangist leaders were getting frustrated with the military's control. In early 1937, they wanted Hedilla to demand that Falange have total political power. They wanted the military to only control the army and navy.

Carlism was a smaller force in the early 20th century. Like Falange, it grew stronger in the mid-1930s. But it was popular only in some parts of Spain. The Carlist leader, Don Alfonso Carlos, died in September 1936. Don Javier became the regent (a temporary ruler). Don Javier met Franco twice in 1936. Both leaders did not trust each other much. Franco preferred to talk to the experienced Carlist leader from Navarre, Conde Rodezno.

Like Falange, the Carlists tried to use the freedom given by the military. In late 1936, Carlist newspapers praised their exiled leader Fal Conde as a "caudillo" (leader). They only put small notes about Franco at the bottom of the page. In early 1937, Carlism started to attract other groups. Some CEDA politicians discussed joining them. In Navarre, the Carlists ran their own kind of government.

Ideas for Political Unity

The military's early statements were very vague about politics. They often talked about "patriotic unity," which were old-fashioned ideas. Since right-wing parties were not banned at first, it seemed like a limited multi-party system might continue. In September 1936, Franco even said he would hand over power to "any national movement" supported by the people. This hinted at elections and political competition.

However, by October, he started talking privately about forcing political groups to unite. The details of this unity were unclear. Some, like Antonio Goicoechea, supported a general "patriotic front." Others suggested a "Partido Franquista" (Franco's Party). People close to Franco, like Nicolas Franco, preferred a civic group called "Acción Ciudadana." These ideas were similar to Primo de Rivera's state party, Unión Patriótica. That party was a big, bureaucratic group built around ideas like patriotism and discipline.

It's not clear if Franco seriously considered these options. By late 1936, he seemed to prefer a different approach. In November, he privately said that Falangist ideas could be used without the Falange party itself. He also asked Falange to propose terms for a merger with the Carlists. In December 1936, the military made the slogan "Una Patria Un Estado Un Caudillo" (One Homeland, One State, One Leader) mandatory for all newspapers. At the same time, party militias were put under army control.

In January 1937, Franco said the country could choose any government. But he also mentioned a "corporative state" (where different groups like workers and businesses work together for the state). He told an Italian visitor that he would create a political group, lead it, and try to unite the parties. People who spoke to him noticed he started saying that the current temporary situation needed a permanent solution. In February, he suggested that Spain's national ideas should be based on Falangism and Traditionalism.

In early 1937, Franco talked with important Italian Fascist leaders. They tried to convince him to create a single state party like in Italy. They thought Franco was confused about politics. It seems Franco expected the Falangists and Carlists to work out the merger terms themselves. Nicolas Franco wrote to Rome that the parties were negotiating and that the main problem was Don Javier, who didn't want to give up power. Experts say Franco thought the Falangists were under control. But he saw the Carlists as stubborn and difficult. He was also annoyed by Falangist ideas about changing society. For example, in February, censors stopped the publication of an old speech by José Antonio that promised to "dismantle capitalism."

Failed Attempts to Unite from Below

The ideas of Falange and Carlism were very different. Falange wanted a revolution led by workers and strong Spanish nationalism, all controlled by a powerful government. Carlism wanted a loose monarchy, a society based on old traditions, and a government that allowed local Basque and Catalan freedoms. Both groups hated democracy and socialism. But they didn't think highly of each other. Falangists saw Carlism as an old, dying group. Carlists saw Falangists as "red scum."

After July 1936, their relationship was mixed. They were allies in the Nationalist group, but they competed for positions and new members. While leaders and frontline fighters got along, in other areas, fights between Carlists and Falangists were common. Sometimes these even turned into gunfights. They sabotaged each other's events and reported each other to the military.

By late 1936, Carlist and Falangist leaders heard about Franco's idea of unification. They decided that a deal agreed by both parties would be better than one forced by the military. But early talks showed big differences. Falange said the Carlists would likely be absorbed by them. Carlists wanted an equal merger into a new party based on their ideas. They wanted it led by three people or with Don Javier as regent. No agreement was reached. But both groups agreed to resist any outside interference.

In late February, more talks happened. The Falangists softened their position a bit. They said Carlism would still be absorbed, but the new party would change a lot. It would accept Carlist ideas and some symbols. It would be led by three people, possibly including Don Javier. But these talks also failed, probably because the Carlist representative, Rodezno, didn't have full permission from Fal and Don Javier.

Other politicians also got involved. Alfonsist leaders like José María Areilza and Pedro Sainz-Rodriguez pushed for unification. They thought they would do better in a multi-party merger. Even Gil-Robles, the CEDA leader, seemed ready to accept unification.

Franco's Final Moves

Franco first thought about unification in October. But it took him five months to work out the details. In February, he was still comparing the ideas of José Antonio and Víctor Pradera. The process sped up in early 1937 when Ramón Serrano Suñer arrived. Serrano was impressed by Italian Fascism and became Franco's main advisor. Franco was also worried about Falange and Carlism becoming too bold. In March, Don Javier and Hedilla sent him letters that mixed loyalty with demands. Falangist meetings showed they wanted political control.

So, in early spring 1937, things got complicated. Franco and Serrano were working on unification terms to force on Falange and Carlism. Both parties tried to agree on their own terms to protect themselves. Also, both Falangist and Carlist leaders were divided among themselves.

By mid-March, the Carlists felt the urgency. They knew unification was coming soon. In late March, a group of Carlist leaders led by Rodezno, who favored a merger, managed to convince Don Javier and Fal to accept the plan. Franco was happy to hear this. But the Carlists still hoped for a deal with Falange, not one forced by the military. In early April, their group planned a common party led by a board. It would have 3 Carlists, 3 Falangists, and 6 of Franco's choices. Franco would be the president. They still hoped this would lead to a Catholic, regional, social, and Traditionalist monarchy.

Another round of talks with Falangists happened on April 11. Only then did Hedilla realize how urgent it was. The parties agreed to keep talking and not allow any outside interference. On April 12, Franco met some Rodeznistas. He told them that unification would be decreed in a few days. He did not tell them the details. Their small concerns were ignored. They were told not to worry.

On April 12, Hedilla told his men that an agreement with the Carlists was almost ready. He called a Falangist meeting for April 26. However, on April 16, his opponents in the Falange leadership visited Hedilla. They told him he was no longer the leader. Both Hedilla's supporters and his opponents believed they had Franco's support. The next day, Hedilla fought back and tried to arrest his opponents. Two people died in a gunfight. Franco's security then arrested most people involved, except Hedilla. On April 18, a small group of Falangist leaders confirmed Hedilla as the new National Chief.

Hedilla rushed to Franco's headquarters and was welcomed warmly. They appeared on a balcony, where Franco gave a short speech. This might have been the first public announcement of unification. At 10:30 PM on April 18, Franco announced the unification on the radio. He gave a long speech about Spain's history and national unity. He said that Falange and Traditionalism had made great contributions. He then said, "we have decided to finalize this unifying work." Most newspapers printed the entire speech on April 19.

The Decree and New Rules

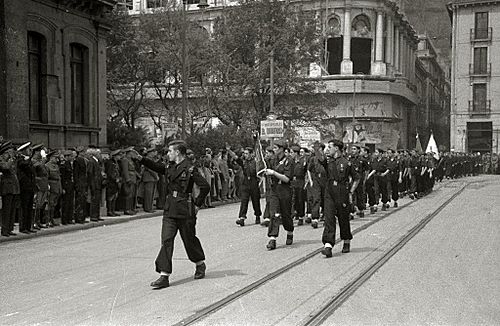

The Unification Decree was first broadcast on Radio Nacional on April 19. On April 20, it appeared in the official government newspaper. It was called Decreto número 255 and was dated April 19. All newspapers in the Nationalist zone printed it. Franco ordered that the decree be read to soldiers on the front lines on April 21. Another decree, dated April 22, was published on April 23. It listed the names of people chosen for the new party's first executive group. Another decree soon followed. It set the salute, symbols, anthem, flag, slogan, and dress code for the new party. It also allowed party militias to use their old symbols until the end of the war.

The Unification Decree stated that "Falange Española" and "Requetés" (Carlist militias) were combined into one "political entity." Franco would lead it. The new party was named "Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS". All members of the old Falange and Carlism were now part of this new group. Other Spaniards could also join. The decree said that "all other political organizations and parties" were dissolved. But it didn't clearly say if the old Falange and Carlism were dissolved too.

The decree also set up the main leadership roles: the Head of State (Franco), the Political Junta (a small executive group), and the National Council. The Political Junta was to help Franco. Half of its members would be chosen by Franco, and half by the National Council. The decree did not say how National Council members would be chosen. All these groups were supposed to work towards a "totalitarian state" (a state with total government control). The decree also said that all party militias would merge into a "National Militia." The new party's program would be based on the original Falange's 26 points. But it could be changed. The new party was meant to be a "link between the state and the society."

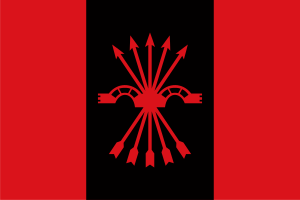

The decree that named the members of the Political Junta listed 10 people. There were 5 Falangists and 4 Carlists. One person was an Alfonsist. Only Hedilla and Rodezno from the old leadership were on the list. The new party adopted original Falangist symbols: the yoke and arrows, the song Cara al sol, and the black-red flag. Its uniform was a mix of a Falangist blue shirt and a Carlist red beret.

Most experts believe Ramón Serrano Súñer wrote most of the unification documents. It's not known exactly when the decrees were written. Neither the Carlists nor the Falangists were involved in writing them. They only learned the terms after the decrees were announced. However, Franco did ask them for some advice. For example, he changed some of his Carlist choices for the Junta based on Rodezno's advice. He also discussed the party's name with Hedilla.

What Happened Next

The terms of unification were a bad surprise for most Falangist and Carlist politicians. The Falangists might have been happy that their ideas and symbols seemed to be in charge. But except for Hedilla, none of their important leaders were chosen for the Political Junta. Hedilla himself was shocked to be just one of 10 Junta members. On April 23, he refused to take his seat. He was quickly arrested, tried, and sentenced to death for treason. His sentence was changed, and he was put in prison.

For Rodezno, the Carlist leader, the terms were a shock. He and his men visited Franco to express their unhappiness. But they did not openly protest. Some key Carlist politicians resigned. Among local leaders and ordinary members, there was confusion. Many thought it was just a new bureaucratic group above their existing organizations. Most did not realize how forced the unification was. They believed their leaders had fully agreed to it. This was because official propaganda said so.

In Falangist ranks, most of whom were new recruits, the unification was seen as simply absorbing Carlism and getting new leaders. But some Falangists protested against the unification in several cities. In Carlist ranks, feelings ranged from excitement to protest. Some Carlist fighter units thought about leaving their positions. Many accepted it as a temporary peace. Most other politicians obeyed. Gil-Robles ordered his party to dissolve. Many party newspapers showed enthusiasm. Various local groups sent messages of support to Franco.

The first steps to combine the new party were taken in late April and May 1937. Franco at first attended the weekly meetings of the Political Junta but soon stopped. Serrano served as the link between Franco and the party leaders. The temporary secretary was López Bassa. Other active figures were Fernando González Vélez (a Falangist) and Gimenez Caballero. Top provincial party jobs were given to a Carlist and a Falangist, alternating as delegate and secretary. 22 provincial leadership roles went to Falangists and 9 to Carlists.

The old Falange and Carlist press departments were told to stop their party propaganda. By May 9, provincial leaders had to list all their old party's assets. In mid-May, the new party started taking over their bank accounts. Also in mid-May, special sections of the new party began to appear. Falangists mostly filled these roles. Civil governors organized rallies to show the unified parties getting along. Official propaganda praised the unification as a glorious end to a long historical process. The first task given to the new party was simple: organize nursing courses.

First Months of Unification

The leaders of Carlism and the original Falange were very cautious. Franco tried to win them over. He sent respectful letters to Don Javier. He also suggested that the exiled Fal Conde be made ambassador to the Vatican. But generally, he left Don Javier no choice but to accept unification. Eventually, Franco allowed Fal Conde back into Spain. He met him in August and vaguely offered him high positions, which Fal politely declined. Both Don Javier and Fal Conde saw Rodezno as a half-traitor. But they didn't want to completely break ties. In late 1937, they focused on saving their related institutions, newspapers, and buildings from being taken over by the new FET party.

For the original Falange, its leaders who were against Hedilla, some released from jail, chose to stay out of it. This included people like Agustín Aznar and Sancho Dávila. They saw unification as "killing two real things to create an artificial one." The new party was strengthened when the original Secretary General, Raimundo Fernández Cuesta, returned from the Republican zone. In October, he was put back in the same job in FET. Unlike Carlism, no effort was made to keep original, independent Falange groups. A small group called Falange Española Auténtica was active from 1937-1939.

Within FET, late 1937 was a time of strong competition between Falangists and Carlists for jobs and assets. About 500 conflicts were officially recorded. By 1942, this number grew to 1,450. The Falangists were clearly winning. The party rules, released in August, set up many specialized sections. Out of 14 leadership roles created, only 3 were held by Carlists. Most gatherings showed continuing divisions. A large youth rally in October in Burgos was meant to show unity. But it turned into an embarrassment when the crowd split into a "blue" Falangist part and a "red" Carlist part in front of Franco.

The unified Carlist leaders were increasingly disappointed about being pushed aside. The original Navarrese Carlist leadership, still active, sent a complaint to Franco. They asked for some changes. In late 1937, many local Carlist leaders who had joined the new FET were now sending angry letters to their men in the Political Junta. They complained about the Falangists not compromising and demanded immediate action. Violent street fights between Falangists and Carlists were common, leading to hundreds of arrests.

In October 1937, Franco decided to set up the National Council of the Movement. This body was vaguely mentioned in the Unification Decree as part of the FET leadership. He simply appointed members. The list of 50 appointees was announced in the media. It was probably ordered by importance. Pilar Primo de Rivera (Falange), Rodezno (Carlism), Queipo de Llano (military), and José Mariá Pemán (Alfonsism) were at the top. There were 24 Falangists, 12 Carlists (mostly Rodeznistas, but also Fal Conde), 8 Alfonsists, 5 high-ranking military men, and 1 former CEDA politician (Serrano Suñer). These appointments marked the end of the first phase of Falange Española Tradicionalista.

Even though the power balance within the new state party was still being decided, some key things were already set. These would not change. They included Franco's strong personal leadership. Also, the original Falange and its ideas would be dominant. Formal groups like the Political Junta and National Council would have mostly symbolic roles. The party would generally depend on government offices.

Impact of the Unification

The main result of unification was creating political unity in the Nationalist side. The most active political groups, which were loyal but also had their own goals, were now controlled. Falange was tamed. Even though strong national-syndicalist ideas remained within FET, Franco and his men now firmly controlled the party. Carlism kept its own political identity outside FET. But it suffered from being split up and started to live a semi-secret life. Neither the Falangists nor the Carlists openly opposed the unification. The most stubborn groups simply chose not to participate.

Key Falangist and Carlist assets, like their volunteer militias, remained loyal to the military leaders. These militias were formally part of the army but kept their political identity. By mid-1937, they had 95,000 men. Because of unification, no major political disagreements were allowed to show up in the Nationalist zone. This was very different from the constant competition and conflicts in the Republican side. Experts say that this formal political unity greatly helped the Nationalists win in 1939.

Another result was a change in the Nationalist government. Before, it seemed like a strong military leadership. Afterwards, it started to look like a political dictatorship. Until April 1937, right-wing political parties were legal. Even though martial law limited their activities, they were somewhat tolerated. After the decree, all political groups except FET were outlawed. FET itself was set up to be fully controlled by Franco and his government.

This change made Franco's position even stronger. It began to shape the system as his personal political dictatorship. Until April, he was the supreme army commander and head of state. These roles defined his military and administrative power. But the Unification Decree gave FET a political monopoly. It named Franco as its leader. This formally established Franco's personal political power. It made him the champion of all political life in the Nationalist zone.

In a few years, FET became a Falange-dominated group controlled by the government. Independent Falange leaders were disciplined and sometimes jailed if they went too far. Others realized that Falangist power in the state party was only possible if Franco was seen as the unquestionable leader. Carlism chose to keep a semi-secret, independent identity. Fal Conde did not accept his seat in the National Council. Don Javier expelled anyone from the party who had accepted without his permission.

Instead of a true unification, the merger turned into Franco's controlled Falange absorbing parts of Carlism. Some Carlists gave up their old identity. Others kept it as a general idea. Still others, like Rodezno, withdrew after some time. The Alfonsists joined half-heartedly. Then they split and most left in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Former CEDA politicians were not welcome.

The new party's early propaganda focused on unity. Or it had confusing ideas, like a "revolutionary program which stems from Spanish tradition." Italians were confused by how much religion was in it. They thought the program was a messy mix, not true "Fascism." Eventually, FET was shaped along syndicalist lines. In Francoist Spain, it became just one of many groups fighting for power. Other groups included the Alfonsists, Carlists, the military, experts, the Church, and government officials.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Decreto de Unificación para niños

In Spanish: Decreto de Unificación para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |