José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

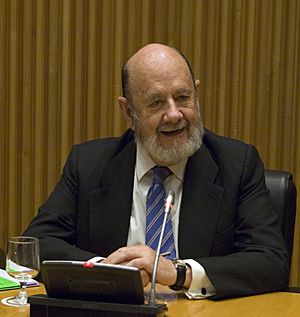

José María Gil-Robles

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Leader of the Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas | |

| In office November 1933 – 19 April 1937 |

|

| Member of the Cortes Generales | |

| In office 28 June 1931 – 17 July 1936 |

|

| Constituency | Salamanca |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 6 May 1935 – 14 December 1935 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones de León

November 27, 1898 Salamanca, Spain |

| Died | September 13, 1980 (aged 81) Madrid, Spain |

| Political party | CEDA (1933–1937) Christian Democratic Party (1977) |

José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones de León (born in Salamanca, Spain, on November 27, 1898 – died in Madrid, Spain, on September 13, 1980) was an important Spanish politician. He led a major political party called the CEDA. He was a key figure in Spain before the Spanish Civil War.

From May to December 1935, he served as the Minister of War. In the 1936 elections, his party, the CEDA, lost. This caused his support to fade away. As the Civil War began, Gil-Robles did not want to compete with Francisco Franco for power. In April 1937, he announced that the CEDA party would close down. He then went to live outside of Spain. While abroad, he talked with Spanish monarchists to plan how they might regain power in Spain. In 1968, he became a professor at the University of Oviedo. He also published his book, No fue posible la paz (meaning 'Peace Was Not Possible'). He was also a member of the International Tribunal at The Hague. After Franco's rule ended, Gil-Robles became a leader of the "Spanish Christian Democracy" party. However, this party did not win much support in the 1977 Spanish general election.

Contents

Biography of Gil-Robles

Early Life and Education

José María Gil-Robles was born in Salamanca, Spain, on November 27, 1898. His father, Enrique Gil Robles, was a conservative Spanish law expert. His family came from León.

José María Gil-Robles earned his master's degree in 1919. In 1922, he became a professor of political law. He taught at the University of La Laguna in Tenerife.

Entering Spanish Politics

During the time of Miguel Primo de Rivera's rule, Gil-Robles worked as a secretary. He was part of the Catholic-Agrarian National Confederation. He also helped write for a newspaper called El Debate.

After the Second Spanish Republic was declared, he joined and later led a party called Acción Nacional (National Action). This party was later renamed Acción Popular (Popular Action).

In the 1931 elections, he was chosen to represent Salamanca in the Cortes, which is like Spain's parliament. During the Republic, he believed that whether Spain was a monarchy or a republic was less important. What mattered most to him was that the country's laws followed religious principles.

Leading the CEDA Party

Gil-Robles created the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA). This was a conservative Catholic party. It aimed to "affirm and defend the principles of Christian civilization."

The CEDA party won the most seats in the elections of November 1933. This made Gil-Robles the leader of the largest party in the Cortes. However, to avoid problems with leftist parties, President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora chose Alejandro Lerroux to be prime minister instead of Gil-Robles. Lerroux was the leader of the Radical Republican Party.

In 1934, three CEDA ministers joined the government. This led to a strike by miners in Asturias. The strike was against the Republic's government, but it was not successful. Gil-Robles served as Minister of War under Lerroux from May to December 1935.

1936 Elections and Aftermath

In the February 1936 Spanish general election, the CEDA was the biggest part of a group called the National Front. This group also included monarchists and Carlists. Gil-Robles campaigned with the slogan Todo el poder para el Jefe, which means "All the power to the Chief."

He was reelected to the Cortes, but the National Front narrowly lost the election. Power then shifted to the left-wing parties. The CEDA itself lost support, winning only 88 seats. This was fewer than the 115 seats it had won in 1933.

After the leftist Popular Front won, support for Gil-Robles and his party decreased. Many of their voters and members joined the Falange party. The Falange had been founded in 1934. The CEDA's youth group, Juventudes de Acción Popular, joined the Falange in large numbers.

In the months that followed, the situation in Spain became very unstable. Gil-Robles knew that a plan was being made to overthrow the government. He later said he was not part of the plan. However, he was kept informed about it. Members of his party helped connect the military and civilian plotters. Gil-Robles himself approved giving 500,000 pesetas (Spanish money) from CEDA's election funds to the military leaders who were planning the uprising.

During the Civil War

When the Spanish Civil War began on July 17, 1936, Gil-Robles did not want to fight Francisco Franco for power. Franco wanted to be the only strong right-wing leader in Spain. In April 1937, Gil-Robles announced that the CEDA party would be dissolved.

After the Civil War, Gil-Robles went to live in another country. While he was away, he talked with Spanish monarchists. They tried to find a way to work together to take power in Spain.

Later Life and Contributions

In 1968, Gil-Robles became a professor at the University of Oviedo. He also published his book, No fue posible la paz ('Peace Was Not Possible'). He was a member of the International Tribunal at The Hague.

After Franco's death and the end of his rule, Gil-Robles became a leader of the Spanish Christian Democracy party. However, this party did not gain much support in the 1977 Spanish general election.

Family Life

Gil-Robles had a son also named José María Gil-Robles. He was born on June 17, 1935, in Madrid. Like his father, he also became involved in politics. He served as a member of the European Parliament. He was also the President of the European Parliament from 1997 to 1999.

Gil-Robles' Legacy

José María Gil-Robles is a very interesting and sometimes debated person in Spanish history. His political ideas during the Second Republic seemed to change a lot. He made statements that sometimes appeared to contradict each other. This was also true for his party, the CEDA. It attracted support from both moderate Catholic republicans and strong right-wing monarchists.

Historians' Views

Historians have different opinions about Gil-Robles.

- Some historians, like Paul Preston, believe that Gil-Robles was a type of leader who wanted to create a strong, controlled government. Preston points to Gil-Robles' speeches, which sometimes had strong anti-democratic ideas. He also notes that Gil-Robles' government partnership with Alejandro Lerroux was very strict. Also, his party's newspaper showed admiration for certain foreign governments. Burnett Bolloten suggests that Gil-Robles knew about the planned uprising in July 1936. He even gave money from CEDA's funds to the military leaders. However, Bolloten also notes that Gil-Robles gave this support somewhat unwillingly. He also refused to join a meeting of right-wing politicians to declare the government unlawful.

- Other historians, like Richard Robinson, disagree. They argue that Gil-Robles was a skilled politician. He tried to keep the right-wing groups in Spain under control and within the law. They believe the CEDA was not just a front for extreme ideas. Instead, it was a party based on Catholic values, aiming for social improvements. Gil-Robles himself sometimes expressed support for the Republic. He once told a journalist, "I am the only friend of the Republic." He also said that a new strict rule would lead to social problems later on. Manuel Tardio and Ramon Arango argue that Gil-Robles did not support a dictatorship. They say he and the CEDA stayed within the rules of the constitution. Burnett Bolloten also notes that Gil-Robles refused to take power with the help of the military and monarchists in May 1935. This was something they never forgave him for. After the Spanish Right won the 1933 elections, he continued to support peaceful change. He wanted to achieve his vision for Spain through gradual steps, even though monarchists and his own party's youth group criticized him.

See also

In Spanish: José María Gil-Robles para niños

In Spanish: José María Gil-Robles para niños