Enrique Gil Robles facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

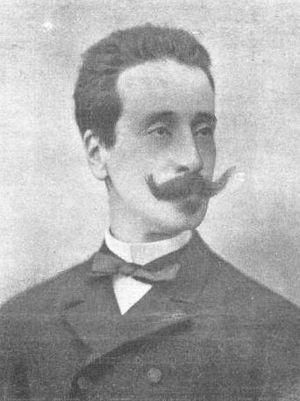

Enrique Gil Robles

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Enrique Gil Robles

1849 Salamanca, Spain

|

| Died | 1908 (aged 58–59) Salamanca, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | academic |

| Known for | scholar, politician |

| Political party | Carlist, Integrist |

Enrique Gil Robles (1849–1908) was a Spanish expert in law and a thinker for the Carlist movement. He is also famous as the father of José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones, a well-known politician. Many scholars see him as one of the main thinkers behind 'Traditionalism' in Spain. Some also consider him important for a legal idea called natural law.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Enrique's family came from Leon. His grandfather, Juan Gil, worked as an administrator in Villafranca del Bierzo. He managed properties for a noble family and the local church. Juan later moved to Ponferrada.

Juan's oldest son, Enrique Gil y Carrasco, became a famous Spanish writer. Enrique's father, Eugenio Gil y Carrasco (1819–?), took over his brother's job as a tax collector. Eugenio also wrote poems and edited his brother's works. He married María Robles Burruezo, and they lived in Salamanca.

Young Enrique lost his mother early in life. He finished high school in Salamanca in 1864. He then studied law at the Salamanca University and later at the Universidad Central in Madrid, graduating in 1868.

Becoming a Professor

In 1870, Enrique started teaching history and other subjects at a school in Ponferrada. He also worked on his PhD in Madrid, finishing it in 1872. By 1875, he became a full professor at the Ponferrada school.

When he was 45, Enrique Gil Robles married Petra Quiñones Armesto from Ponferrada. They had three children. Their youngest son, José María, became a very famous politician in Spain. He was the leader of a group called CEDA. Enrique's grandson, José María Gil-Robles y Gil-Delgado, also became a leading politician and was president of the European Parliament.

Academic Career

In 1875, Gil Robles successfully competed for a professor position at his home university in Salamanca. He became a full professor of political and administrative law in 1876. He held this job for 32 years, until just before he died.

Gil Robles tried to move to other universities several times. He applied for positions in Barcelona and Madrid, but these attempts were not successful. Sometimes, the rules for applying seemed to change, which made it harder for him.

Growing Influence

At first, some people in Salamanca didn't know much about Gil Robles. But he slowly became more recognized. He often served as a judge for other professors' applications and attended national law conferences. Students liked him because he taught clearly and was kind.

By the 1890s, Gil Robles was one of the most respected scholars in Salamanca. He and other thinkers who followed the ideas of Thomism (a philosophy based on Thomas Aquinas) made the university known for its conservative views. Even when new professors with different ideas arrived, Gil Robles remained a very important figure at the university until his death.

His Writings

Enrique Gil Robles did not write a lot of books. His main works include one big book, a few smaller ones, and some articles. He also wrote for newspapers, but we don't know exactly how much. His writings cover three main areas: how a state should work, the theory of law, and education. Most of his important works were published between 1891 and 1902.

His most important work was Tratado de derecho político según los principios de la filosofía y el derecho cristianos (Treaty on Political Law according to Christian Philosophy and Law). This book, published in 1899 and 1902, was over 1,100 pages long. It explained his ideas on how a state should be organized and the rules of public law. It also shared his thoughts on politics, history, and religion.

Other Important Works

Two other important, but shorter, books are El absolutismo y la democracia (1891) and Oligarquía y caciquismo. Naturaleza. Primeras causas. Remedios. Urgencia de ellos (1901). These books were based on lectures he gave about problems in Spanish politics.

He also wrote about education. His book El catolicismo liberal y la libertad de enseñanza (1896) compared Catholic and liberal ways of teaching. He also wrote more technical guides for studying law.

None of his works were printed again until 1961. Today, some scholars describe his work as "very ample," meaning very detailed and thorough.

His Ideas

Many scholars believe Gil Robles's ideas continued the Traditionalist thinking of the 19th century. He saw Liberalism as the main problem in Spain. He thought it had destroyed traditional ways of life and replaced them with a system where a few rich people (an oligarchy) held power.

Gil Robles believed Spain should return to the spirit of the old system. His main ideas were about an "organic society" and a powerful, but limited, king.

Organic Society

According to Gil Robles, people are not all equal or completely free. They belong to different groups in society. Society is not just a collection of individuals, but a structure made of these groups. He compared it to a living body with different parts working together. This is why he called it an "organic society."

He believed that each group should have its own freedom to govern itself. He called this "autarquía." Society had three main layers: nobles, middle class, and working class. Each had different roles. He thought that true democracy meant recognizing the roles and freedom of these groups. He believed society was held together by how its parts depended on each other, not by any "social contract."

Role of the State

Gil Robles thought that political representation should not be based on everyone voting (universal suffrage). He believed this led to corruption and a few powerful people controlling things. Instead, he thought representatives should come from different groups or professions.

He imagined a parliament with two parts. One part would represent different regions and workers. The other part would be made of selected nobles. He believed the state should be smaller and only handle basic tasks. Most governing should be done by the social groups themselves. He thought a strong state only became necessary when society couldn't govern itself.

He believed a king should lead the state. This king would have political power but would be limited by the self-governance of the social groups. He did not believe in separating powers into legislative, executive, and judicial branches. However, he did say that a king could use strong, even dictatorial, power if it was absolutely necessary to save the country.

Political Life

It's not clear how Gil Robles became so conservative. He was in Madrid during the 1868 revolution, which might have influenced him. He became close to Ramón Nocedal, another conservative leader. In 1869, Gil Robles helped start a Catholic youth group in Salamanca. He gave speeches with strong Traditionalist ideas and was mentioned in Carlist newspapers.

He stayed active in the Traditionalist movement. He helped organize a large trip to Rome in 1882 for Catholics. He also supported Carlist projects, like trying to build a monument for a Carlist general. By the mid-1880s, he was a leader of Traditionalism in Salamanca.

Joining the Integrists

In 1888, Gil Robles joined a group that broke away from the Carlists, led by Nocedal. This group was called the Integrists. He helped organize their party in 1889. In the 1891 election, he ran for parliament as an Integrist, but he lost. He did not run again in 1893.

Over time, his relationship with Nocedal cooled. Gil Robles was uncomfortable with the Integrists' strong attacks on the Carlist leader. In 1899, he tried to bring the Carlists and Integrists back together, but Nocedal refused. Soon after, Gil Robles and Nocedal had a public disagreement.

Return to Carlism

After leaving the Integrists, Gil Robles returned to the main Carlist party. He exchanged friendly letters with Carlos VII, the Carlist claimant. He started writing for the Carlist newspaper, El Correo Español.

In 1903, he ran for parliament again, this time as a Carlist, and won in Pamplona. In parliament, he spoke for the Carlist group. He was active on many issues, including education, law, and foreign policy. He did not run in the 1905 or 1907 elections, but he continued to write for the Carlist newspaper.

Life in Salamanca

Gil Robles was very active in Salamanca. He joined local committees, became a member of the local law academy, and was elected to the city council in 1893. He also contributed to Salamanca's Traditionalist newspapers.

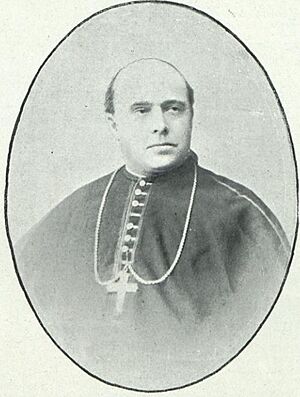

He was involved in two long-running conflicts with other important people in Salamanca. One was with the local bishop, Tomás Cámara y Castro. The bishop disagreed with the Integrists' strong views and banned Catholics from reading their newspapers. Gil Robles fought back, even appealing to Rome. This conflict lessened when Gil Robles left the Integrists.

Conflict with Unamuno

After 1891, conservatives like Gil Robles largely controlled the academic world in Salamanca. A young professor named Miguel de Unamuno arrived in Salamanca and soon clashed with Gil Robles. Unamuno wrote articles criticizing Gil Robles, calling him "unfit" and saying he wanted to bring back the Middle Ages.

While Unamuno later softened his tone, their relationship remained difficult. Unamuno and another professor, Pedro Dorado Montero, worked to challenge the conservative control of the university. They gained more influence after Gil Robles's death.

See also

In Spanish: Enrique Gil Robles para niños

In Spanish: Enrique Gil Robles para niños