European Parliament facts for kids

Quick facts for kids European Parliament

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th European Parliament | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type |

De facto lower house

of bicameral legislature |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Term limits

|

None | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Founded | 10 September 1952 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leadership | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Roberta Metsola, EPP

Since 18 January 2022 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Secretary-General

|

Alessandro Chiocchetti, Independent

Since 1 January 2023 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Structure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Seats | 720 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Political groups

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- ESN (27)

- NI (30)

- Vacant (1)

| committees1 =

Budgetary Control

Economic & Monetary Affairs

Employment & Social Affairs

Environment, Public Health & Food Safety

Industry, Research & Energy

Internal Market & Consumer Protection

Transport & Tourism

Regional Development

Agriculture & Rural Development

Fisheries

Culture & Education

Legal Affairs

Civil Liberties, Justice & Home Affairs

Constitutional Affairs

Women's Rights & Gender Equality

Petitions

Foreign Affairs

- Human Rights

- Security & Defence

Development

International Trade

| joint_committees = | term_length = 5 years | authority = | salary = €8,932.86 monthly | seats1_title = | seats1 = | voting_system1 = Chosen by member state.

Systems include:

- Party list PR

- STV in Ireland and Malta

- de facto FPTP/SMP

(only in the German-speaking

electoral college in Belgium)

| first_election1 = 7–10 June 1979 | last_election1 = 6–9 June 2024 | next_election1 = 2029 | redistricting = | motto = In varietate concordia

(United in diversity) | session_room = European Parliament hemicycle.jpg | session_res = 300px | session_alt = European parliament hemicycle in Strasbourg, France | meeting_place = Louise Weiss Building

Strasbourg, France | session_room2 = Euroopan parliaementin istuntosali (Brysselissä).jpg | session_res2 = 300px | session_alt2 = Euroopan parliaementin istuntosali (Brysselissä).jpg | meeting_place2 = Espace Léopold

Brussels, Belgium | website = | constitution = Treaties of the European Union | footnotes = }}

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the main law-making bodies of the European Union (EU). It is one of the EU's seven important institutions. The Parliament works with the Council of the European Union to create European laws. These laws are first suggested by the European Commission.

The Parliament has 720 members, called MEPs. These members were elected in June 2024. This makes it the second-largest group of voters in the world, with about 375 million people able to vote in 2024.

Since 1979, people in the EU have directly elected the Parliament every five years. This is done through a system where everyone can vote. The number of people who voted went down after 1979 until 2019. In 2019, more people voted, and the turnout went above 50% for the first time since 1994. Most EU countries allow people to vote at age 18. However, in Malta, Belgium, Austria, and Germany, you can vote at 16. In Greece, you can vote at 17.

The European Parliament helps make laws for the EU. It usually needs to approve new laws along with the Council. This is like having two parts of a government that make laws. The Parliament cannot start a new law on its own. Only the European Commission can formally suggest new laws. But the Parliament and the Council can ask the Commission to propose a law.

The Parliament is considered the "first institution" of the EU. It has equal power with the Council over laws and the EU's budget. The European Commission, which carries out the EU's decisions, is answerable to the Parliament. The Parliament decides whether to approve the person chosen to lead the Commission. It also approves or rejects the entire group of people who will be in the Commission. If needed, the Parliament can even make the Commission resign.

The President of the European Parliament leads the Parliament's meetings. The five largest political groups are the European People's Party Group (EPP), the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), Patriots for Europe (PfE), the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR), and Renew Europe (Renew). The most recent EU-wide election was in 2024.

The Parliament's main office is in Strasbourg, France. Its administrative offices are in Luxembourg City. Full meetings are usually held in Strasbourg for four days each month. Sometimes, extra meetings happen in Brussels. Most committee meetings are held in Brussels, Belgium. So, the Parliament works three weeks a month in Brussels and one week in Strasbourg.

Contents

How the European Parliament Started

The European Parliament, like other EU bodies, did not start in its current form. It first met on September 10, 1952. It began as the Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). This was a group of 78 appointed lawmakers from different countries. They did not have the power to make laws.

One expert, Professor David Farrell, said that for a long time, the European Parliament was just a "multi-lingual talking shop." This means people talked a lot, but not much happened.

The way the EU has grown shows that there was no clear plan from the beginning. Even the Parliament's three working locations have changed many times. Most MEPs would prefer to work only in Brussels. But in 1992, France made sure that Strasbourg would remain the official seat.

From Assembly to Parliament

The idea for this body was not in the first plans for European cooperation. It was hoped that an existing group, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, could handle law-making. But a separate Assembly was created to keep an eye on the executive branch and ensure democratic fairness. The early treaties showed a desire for more than just a talking group. They even allowed for direct elections.

The Assembly's early importance was clear when it was asked to write a draft treaty for a European Political Community. This group was formed in 1952 with more members. But the plan was dropped after another idea, the European Defence Community, failed.

Instead, the European Economic Community and Euratom were created in 1958. The Common Assembly was used by all three groups. It then changed its name to the European Parliamentary Assembly. The first meeting was on March 19, 1958, in Luxembourg City. The members decided to sit together based on their political ideas, not their home country. This is seen as the start of the modern European Parliament.

The three communities later joined together as the European Communities in 1967. The body's name changed to the "European Parliament" in 1962. In the 1970s, the Parliament gained power over parts of the EU's budget. By 1975, it had power over the entire budget. The original treaties said the Parliament should be elected. But countries could not agree on a single voting system. So, they agreed to hold elections with each country using its own system.

Until 1999, the Parliament met in the same buildings as the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg.

Direct Elections and More Power

In 1979, people directly elected the members of the European Parliament for the first time. This made it different from other similar groups whose members are appointed. After this first election, the Parliament met on July 17, 1979. They elected Simone Veil as their President. She was the first woman to lead the Parliament.

As an elected body, the Parliament started to suggest ideas for how the EU should work. For example, in 1984, it drafted a treaty to create a "European Union." Many of these ideas were later used in other treaties. The Parliament also started to vote on who should be the head of the European Commission, even before it had the official right to do so.

Since it became an elected body, the number of members in the European Parliament has grown as new countries joined. The Treaty of Nice set a limit of 732 members, which later increased to 751 with the Treaty of Lisbon.

The Parliament's main location was still not fixed. The temporary plan had Parliament in Strasbourg, while the Commission and Council were in Brussels. In 1985, the Parliament built a second meeting room in Brussels to be closer to other EU bodies. A final agreement was reached in 1992. It said that Strasbourg would be the official seat for twelve sessions a year. All other Parliament activities would be in Brussels. The Parliament did not like this two-seat arrangement, but it was made official in the Treaty of Amsterdam. Even today, the Parliament's different locations cause debate.

The Parliament gained more power through new EU treaties. This included more say in law-making and the right to approve international agreements.

In 1999, the Parliament made the Santer Commission resign. The Parliament refused to approve the EU budget because of concerns about how money was managed. This was the first time the Parliament forced a Commission to resign.

Parliament's Role in Approving Leaders

The Parliament has always had the power to remove the European Commission. But at first, it had no say in choosing the Commission. In the 1992 Treaty of Maastricht, countries gave the Parliament the right to approve or reject a new Commission. In the 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam, they gave it the right to approve or reject the person chosen to lead the Commission.

In 2004, after the biggest election across many countries, the European Council suggested José Manuel Barroso to lead the Commission. He was from the largest political party. The Parliament approved him. However, when it was time to vote on the whole Commission, MEPs had concerns about some of the people chosen. This led to some changes before the Parliament approved the Commission.

The Parliament also became more active in changing proposed laws. A good example was the Bolkestein directive in 2006. The Parliament voted for many changes that completely changed the law. This showed that the directly elected MEPs were becoming a strong and effective EU institution.

In 2007, the Justice Commissioner, Franco Frattini, included the Parliament in talks about a new information system. This was important because, at that time, MEPs only needed to be asked for their opinion on parts of the plan. This showed that the Parliament was gaining more influence.

Recent Developments

From 2007 to 2009, a special group worked to make the Parliament more modern. They made changes like giving more speaking time to those presenting reports and improving teamwork among committees.

The Treaty of Lisbon started on December 1, 2009. It gave the Parliament power over the entire EU budget. It also made the Parliament's power to make laws almost equal to the Council's in most areas. The treaty also said that the Parliament "elects" the person who will lead the Commission. The European Council must consider the election results when choosing this person.

In 2009, Barroso was supported by the European Council for a second term. The Parliament also approved him. When Barroso suggested people for his new Commission, MEPs again had concerns about one nominee. This person had to step down.

Before the final vote on the Commission, the Parliament asked for some agreements for how they would work together under the new Lisbon Treaty. This included the Parliament's President attending important Commission meetings. The Parliament also gained a role in international talks led by the Commission.

In October 2023, the Parliament passed a resolution. It condemned "Hamas' terrible attacks against Israel."

What the Parliament Does

The Parliament and the Council are like the two main parts of a law-making body. However, there are some differences from national parliaments. For example, neither the Parliament nor the Council can start a new law on their own. This power belongs only to the European Commission. So, while the Parliament can change or reject laws, it needs the Commission to write a bill first.

The Parliament also has a lot of indirect influence. It can pass non-binding resolutions and hold committee hearings. It acts as a "pan-European soapbox," meaning it's a place where ideas are discussed widely. The Parliament also affects foreign policy. It must approve all grants for development, including those overseas. For example, money for rebuilding after a war or for encouraging countries to stop nuclear development needs Parliament's support.

How Laws are Made

With each new treaty, the Parliament's power in making laws has grown. The main way laws are made is called the "ordinary legislative procedure" (formerly "codecision procedure"). This process gives equal power to the Parliament and the Council.

Here is how it generally works:

- The Commission suggests a new law to the Parliament and the Council.

- The law can only pass if both agree on the text.

- This can happen through up to three readings.

- In the first reading, the Parliament can suggest changes to the Council.

- The Council can accept these changes or send back its own version.

- If the Council sends back its version, the Parliament can approve it, reject it, or suggest more changes.

- If they still don't agree, a "Conciliation Committee" is formed. This committee has members from both the Council and the Parliament. They try to find a compromise.

- Once they agree, the Parliament must approve it.

In reality, most laws are agreed upon in the first reading. The Parliament and Council negotiate a compromise text in meetings called "trilogues." The Commission is also present at these meetings.

In a few areas, special law-making procedures are used. These include justice, home affairs, budget, and taxes. In these cases, either the Council or the Parliament makes the law alone, after asking for the other's opinion or getting their approval.

There are different types of EU laws:

- A regulation is a law that applies directly and fully in all member states.

- Directives set goals for member states to achieve. Countries can choose how to reach these goals through their own laws.

- A decision applies to a specific person or group.

- Institutions can also give recommendations and opinions, which are not binding.

Budget Power

The Parliament and the Council are also in charge of the EU's budget. This has been the case since the 1970s and the Lisbon Treaty. The EU budget is approved using a process similar to law-making. The Parliament has power over the entire budget, equal to the Council. If they disagree, a conciliation committee helps them find a solution. If the Council does not approve the final budget, the Parliament can still pass it with a three-fifths majority vote.

The Parliament also checks how past budgets were spent. It has refused to approve the budget only twice. One time, in 1998, this led to the Santer Commission resigning. This shows how much power the Parliament has over the Commission.

Checking the Executive Branch

The President of the European Commission is suggested by the European Council. This choice is based on the results of the European elections. The Parliament must approve this person by a majority vote. After the President is approved, the members of the Commission are suggested by the President. Each person chosen to be a Commissioner appears before a Parliament committee. Then, the Parliament votes to approve or reject the entire group of Commissioners.

The Parliament has never voted against a President or their Commission. But the threat of doing so has led to changes in the Commission's members or policies. For example, when the Barroso Commission was first proposed, the Parliament pushed for changes to make it more acceptable. This pressure showed how the Parliament was growing in its ability to hold the Commission accountable. When voting on the Commission, MEPs usually vote with their political group, not just their home country. This unity and willingness to use its power has made national leaders pay more attention to the Parliament.

The Parliament can also remove the Commission with a two-thirds majority vote. This power has never been used directly. But when faced with such a vote, the Santer Commission resigned on its own.

Other ways the Parliament checks the executive include:

- The Commission must give reports to the Parliament and answer questions from MEPs.

- The head of the Council must present their plans at the start of their term.

- The President of the European Council must report to Parliament after meetings.

- MEPs can ask the Commission to propose new laws or policies.

- MEPs can question members of other EU institutions.

Oversight and Scrutiny

The Parliament also has other powers to oversee EU activities. It can set up special committees to investigate issues, like the one for mad cow disease. The Parliament can ask other institutions to answer questions. If needed, it can even take them to court if they break EU law.

The Parliament also approves the people chosen for the Court of Auditors and the leaders of the European Central Bank. The head of the European Central Bank must give a yearly report to the Parliament.

The European Ombudsman is chosen by the Parliament. This person handles complaints from the public about bad management by any EU institution.

Any EU citizen can send a petition to the Parliament about something within the EU's work. The Parliament's Committee on Petitions hears these cases, sometimes with the citizen present. The Parliament tries to solve the problem as a mediator. If needed, they can use legal steps to help resolve the dispute.

Who are the Members?

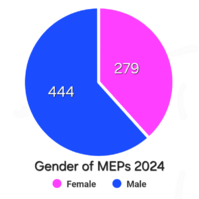

The lawmakers are called Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). They are elected every five years by direct vote. They sit in the Parliament based on their political group. About 40 percent of MEPs are women. Before the first direct elections in 1979, they were chosen by their national parliaments.

The Parliament has been criticized for not having enough members from minority groups. In 2017, only about 17 MEPs were not white. After the 2019 European Parliament election, about 5% of MEPs were from racial and ethnic minorities. This is lower than the estimated 10% of Europe's population who are from these groups.

Under the Treaty of Lisbon, the number of seats for each country is based on its population. The maximum number of members is 751. Since February 1, 2020, after the United Kingdom left the EU, there are 705 MEPs. This number increased to 720 after the 2024 elections.

Currently, no country can have more than 96 seats or fewer than 6 seats. This is to make sure that larger countries have more MEPs, but smaller countries still have a fair say. For example, Germany (with about 80.9 million people) has 96 seats. This means one MEP represents about 843,000 people. Malta (with about 0.4 million people) has 6 seats. This means one MEP represents about 70,000 people.

The new system under the Lisbon Treaty was designed to avoid political bargaining when seats need to be changed due to population shifts.

Countries are divided into areas called constituencies for elections. Some countries, like Belgium, Ireland, Italy, and Poland, divide their land into several constituencies. Most other countries treat the whole country as one constituency. All EU countries use different forms of proportional representation for these elections. This means that parties get seats based on the percentage of votes they receive.

Salaries and Expenses

Before 2009, MEPs earned the same salary as lawmakers in their own countries. But since 2009, all MEPs receive the same monthly pay. In 2016, this was €8,484.05. This money is taxed by the EU and can also be taxed by their home country. MEPs can also get a pension from the Parliament when they turn 63.

MEPs also receive money for office costs, living expenses, and travel. They get special privileges and immunities. This helps them travel freely to and from the Parliament. In their home country, they have the same protections as national lawmakers. In other countries, they are protected from being arrested or taken to court. They can only be prosecuted if the European Parliament agrees to remove their immunity. However, they cannot claim immunity if they are caught committing a crime. The Parliament can also take away an MEP's immunity.

Political Groups

MEPs in the Parliament are organized into eight different parliamentary groups. Members who do not join a group are called non-attached members.

The two largest groups are the European People's Party Group (EPP) and the Socialists & Democrats (S&D). These two groups have been the most powerful in the Parliament for a long time. They held between 50% and 70% of the seats until 2019. No single group has ever had a majority on its own.

Political groups in the European Parliament are made up of many national parties. They are more like parties in countries with federal systems, like Germany or the United States. They are not as tightly controlled as parties in single countries.

Half of the groups are based on a single European political party. Others, like the Greens–European Free Alliance or the European Conservatives and Reformists Group, are based on two European parties. They also include other national parties and independent members.

To form a group, there must be at least 23 MEPs from seven different member states. Once a group is formed, it receives public money from the Parliament's budget.

Working Together

Since the Parliament does not form a government in the usual way, majorities are built for each issue. This often involves different groups working together to find common ground.

Usually, the European People's Party and the Socialist and Democrat Group work together. They try to find compromises and then bring in other groups. This relationship has been called a "grand coalition." However, they don't always agree. Each group might try to form alliances with other parties. The EPP often works with other center-right or right-wing groups. The S&D works with center-left or left-wing groups. Sometimes, the Liberal (Renew Europe) Group holds the deciding votes.

There have been times when political groups strongly disagreed. For example, when the Santer Commission resigned, the two main parties acted like a government and opposition. The Socialists supported the executive, while the EPP voted against it. This kind of strong political division has become more common.

After the 2019 European Parliament election, the EPP-S&D coalition lost its majority. This means they now need support from at least one other political group, often the Renew Group or the Greens, to get a majority.

Elections

Elections have been held directly in every member state every five years since 1979. As of 2019, there have been nine elections. If a country joins the EU between elections, a special election is held for its representatives. This happened six times, most recently when Croatia joined in 2013.

Elections take place over four days, from Thursday to Sunday. Each member state chooses its voting day. Countries choose their own voting system, but it must be fair and use proportional representation. This means that parties get seats based on the percentage of votes they receive. Seats are given to member states based on their population. Since 2014, no state can have more than 96 seats or fewer than 6 seats.

The most recent EU-wide elections were the European elections of 2024, held from June 6 to 9, 2024. These were the largest simultaneous elections across many countries ever held. The first session of the tenth Parliament began in July 2024.

European political parties are the only ones allowed to campaign during the European elections. There have been ideas to make the elections more interesting to the public. One new idea in the 2014 elections was that the main European political parties announced their candidates for President of the European Commission before the elections. These candidates are called Spitzenkandidaten (German for "leading candidates"). The European Council, which represents the governments of member states, nominates the President of the European Commission. While they don't have to choose the winning "candidate," the Lisbon Treaty says they should consider the election results. The candidate they propose must be approved by a majority of MEPs.

In 2014, Jean-Claude Juncker for the European People's Party won the most seats. He was nominated by the European Council and elected by the Parliament.

In 2019, parties again announced their candidates. But after the election, the parties could not agree on any of them. After a period of disagreement, the European Council suggested Ursula von der Leyen as a compromise. The Parliament elected her, though by a small majority.

In 2024, the EPP supported Von der Leyen for a second term. The PES supported Nicolas Schmit.

Until 2014, the number of people who voted dropped in every election since the first one. From 1999 to 2014, less than 50% of people voted. This changed in the 2019 election, when turnout increased by 8% across the EU, reaching 50.6%. This was the highest since 1994.

How Meetings Work

The European Parliament has a yearly "session." This is divided into monthly "part-sessions" and daily "sittings." This means there is a monthly cycle:

- Two weeks for committees to discuss topics.

- One week for political groups to discuss their work.

- One week (3.5 days) for full meetings in Strasbourg.

- Six extra 2-day meetings are held in Brussels throughout the year.

- Four weeks a year are for MEPs to work only in their home areas.

- There are no meetings planned during the summer.

The Parliament can meet without being called by another authority. Its meetings are partly set by treaties and partly by its own rules.

During meetings, members can speak after the President calls on them. Members of the Council or Commission can also attend and speak. Debates are usually calm and polite. This is partly because of the need for interpretation into many languages. Voting is usually done by a show of hands. If requested, it can be checked by electronic voting. Votes are not always recorded, but they are for final votes on laws or if a group of MEPs asks for it. All recorded votes and laws are published online. Votes are usually grouped together at specific times, often around noon. This is to avoid disrupting other meetings.

Members sit in a semicircle based on their political groups. All desks have microphones, headphones for listening to interpretation, and electronic voting equipment. The leaders of the groups sit in the front. In the very center is a podium for guest speakers. The President and staff sit in a raised area. The Council sits on the far left, and the Commission sits on the far right. Both the Brussels and Strasbourg meeting rooms are set up this way.

Access to the meeting room is limited. Ushers control entry and help MEPs. They can also enforce the President's rules, like removing an MEP who is causing trouble. The ushers wear black tailcoats and silver chains. They are recruited like other EU civil servants. The President has a personal usher.

President and How Parliament is Organized

The President is like the speaker of the Parliament. They lead the full meetings. The President's signature is needed for all laws and the EU budget. The President also represents the Parliament to the outside world and makes sure the rules are followed. The President is elected for two-and-a-half-year terms. The current President is Roberta Metsola, who was elected in January 2022.

In most countries, the head of state comes first in official ceremonies. But in the EU, the Parliament is listed as the first institution. So, its President ranks higher than other European or national leaders in official protocol.

Many important people have been President of the Parliament. The first President was Paul-Henri Spaak, one of the EU's founders. Other founders like Alcide de Gasperi and Robert Schuman also served. Three women have been President: Simone Veil in 1979 (the first President of the elected Parliament), Nicole Fontaine in 1999, and Roberta Metsola in 2022. The previous president, Jerzy Buzek, was the first from Central and Eastern Europe. He was a former Prime Minister of Poland and part of the Solidarity movement that helped end communism.

During the election of a President, the previous President leads the meeting. If they cannot, one of the previous Vice-Presidents does. Before 2009, the oldest member did this.

The Parliament also elects 14 Vice-Presidents. They lead debates when the President is not there. Several groups help run the Parliament. The Bureau handles money and administration. It includes the President and Vice-Presidents. The Conference of Presidents is the political governing body. It includes the President of the Parliament and the leaders of each political group. Five Quaestors look after the financial and administrative needs of the members.

In 2014, the European Parliament's budget was €1.756 billion. A report in 2008 found some overspending.

Committees and Delegations

The Parliament has 20 Standing Committees. Their size ranges from 25 to 88 MEPs. Each committee reflects the political makeup of the whole Parliament. They include a chair, a bureau, and staff. They meet twice a month in public. They prepare, change, and approve proposed laws and reports to be presented to the full Parliament. The people who write reports for a committee are supposed to present the committee's view.

The Parliament can also create smaller sub-committees or temporary committees for specific topics. The chairs of the committees work together through the "Conference of Committee Chairmen."

The committees are different from national ones. They are large for European standards, with many staff members. They also have access to a lot of administrative, archive, and research resources.

Delegations of the Parliament are formed in a similar way. They handle relationships with parliaments outside the EU. There are 44 delegations, most of them small. The leaders of the delegations also work together. Delegations include groups that connect with parliaments outside the EU, with countries that want to join the EU, and with other international assemblies. MEPs also take part in other international activities, like observing elections in other countries.

Intergroups

Intergroups in the European Parliament are informal groups. They bring together MEPs from different political groups to discuss any topic. They do not speak for the European Parliament as a whole. They help discuss topics that cross over different committees and in a less formal way. Their daily work can be managed by MEPs' offices or by interest groups. Any financial support they receive must be officially declared. Intergroups are created or renewed at the start of each new Parliament term. A proposal for an Intergroup must be supported by at least three political groups.

Translation and Interpretation

Speakers in the European Parliament can speak in any of the 24 official EU languages. These range from French and German to Maltese and Irish. Simultaneous interpretation is provided in all full meetings. All final laws are translated. With 24 languages, the European Parliament is the most multilingual parliament in the world. It is also the biggest employer of interpreters globally.

Usually, a language is translated into the interpreter's native language. Because there are so many languages, sometimes interpreting is done the other way around. Also, a speech in a less common language might be translated through a third language if there are not enough interpreters. Interpreters need to understand the political meaning of a speech, not just translate word for word. This requires a lot of preparation. It can be difficult when MEPs use jokes or speak too fast.

Some people believe speaking their native language is important for their identity. But interpretation and its cost have been criticized. A 2006 report showed that using only English, French, and German could greatly reduce costs.

Annual Costs

According to the European Parliament's website, its budget for 2021 was €2.064 billion. This is about 1.2% of the total EU budget. The main costs are:

- 45% for staff (salaries, language services).

- 22% for running costs (buildings, IT).

- 26% for political activities (members, political groups).

- 6% for communications.

A 2013 study found that having the Strasbourg seat costs an extra €103 million compared to having only one location. The Court of Auditors said an additional €5 million is spent on travel because of the two seats.

For comparison, the German parliament (Bundestag) cost about €517 million in 2018 for 709 members. The British House of Commons cost about £249 million (€279 million) in 2016–2017 for 650 seats.

The Economist newspaper said that the European Parliament costs more than the British, French, and German parliaments combined. About a quarter of the costs are for translation and interpretation (€460 million). The two seats are estimated to add another €180 million a year.

In July 2018, MEPs rejected ideas to make rules stricter for the General Expenditure Allowance (GEA). This is a €4,416 monthly payment MEPs receive for office and other costs. They are not required to show how they spend this money.

Where the Parliament Meets

The Parliament has offices in three different cities. The EU treaties require 12 full meetings to be held in Strasbourg. This is the Parliament's official seat. Extra meetings and committee meetings are held in Brussels. Luxembourg City is home to the Parliament's administrative offices. The European Parliament is one of the few parliaments in the world with more than one meeting place. It is also one of the few that cannot decide its own location.

The Strasbourg seat is seen as a symbol of peace between France and Germany. But the cost and trouble of having two seats are often questioned. While Strasbourg is the official seat, Brussels is home to almost all other major EU institutions. Most of the Parliament's work happens there. Critics call the two-seat arrangement a "travelling circus." Many people want Brussels to be the only seat.

This idea is supported by many, including Margot Wallström, a former Vice-President of the Commission. She said that what was once a positive symbol has become a negative one, showing wasted money and bureaucracy. The European Green Party also pointed out the environmental cost. Besides the extra €200 million spent, there are over 20,268 tonnes of extra carbon dioxide emissions. This goes against the EU's environmental goals. A petition with a million signatures also supports this campaign. In 2014, the European Court of Auditors estimated that moving the Strasbourg seat to Brussels would save €113.8 million per year.

Most MEPs prefer Brussels as a single base. A poll of MEPs found that 89% wanted a single seat, and 81% preferred Brussels. Another survey found 68% support. In July 2011, a majority of MEPs voted for a single seat. However, the Parliament's seat is fixed by treaties. It can only be changed if all member states agree, and France could veto any move. Former French President Nicolas Sarkozy said the Strasbourg seat is "non-negotiable."

However, the main building in Brussels has been in poor condition for over ten years. Renovating or rebuilding it was estimated to cost at least €500 million in 2017. Some feared the cost could go up to €1 billion. The Strasbourg seat already has a fully working meeting room.

Talking to Citizens

MEPs are the main way citizens can connect with the Parliament. MEPs usually have an office in their home area. They travel back each week to meet with voters, businesses, and local authorities.

The Parliament also has a detailed website. It receives about one million visitors a year. It also streams debates and committee meetings online.

EU institutions have promised to be open and transparent about their work. Transparency is seen as very important for EU institutions. It helps make the EU more democratic. The treaties say that "every citizen shall have the right to participate in the democratic life of the Union." Decisions should be made as openly as possible and close to the citizens. Both treaties also value talking between citizens, groups, and EU institutions.

Talking with Religious Groups

Article 17 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) sets the rules for open talks between EU institutions and religious groups. In July 2014, the President of the European Parliament, Martin Schulz, asked Antonio Tajani to lead this dialogue. The European Parliament hosts high-level meetings on inter-religious dialogue. These meetings focus on current issues related to the Parliament's work.

Mediator for Child Abduction

The role of European Parliament Mediator for International Parental Child Abduction was created in 1987. It helps children of international parents who have been taken by one parent after the parents separate. The Mediator helps find solutions that are best for the child through discussion. The Mediator is asked to help by a citizen. After reviewing the request, the Mediator starts a process to reach an agreement. Once both parents and the Mediator sign the agreement, it is official. This agreement is a private contract between the parents. The European Parliament provides legal support to make sure the agreement is fair and legal. The agreement can be approved by national courts. It can also be the basis for a separation or divorce.

Research and Information

The European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) is the Parliament's own research department. It provides MEPs and committees with independent and reliable information. This helps them in their work and to check on the European Commission and other EU executive bodies.

The EPRS offers many services and has experts in all policy areas. This helps MEPs and committees with knowledge. It also helps the Parliament be more effective and influential. The EPRS also helps the Parliament connect with the public. All EPRS publications are available online.

Public Opinion Surveys

The European Parliament regularly orders surveys and studies on public opinion in member states. These surveys check what citizens think about the Parliament's work and the EU's activities. Topics include how citizens see the Parliament's role, their knowledge of the institution, their feeling of belonging to the EU, and their opinions on elections and European integration. They also cover identity, citizenship, political values, and current issues like climate change and the economy. These surveys aim to show a full picture of different countries, regions, and social groups.

Awards and Prizes

Sakharov Prize

The Sakharov Prize was created in 1988. The European Parliament gives this award to people who help promote human rights around the world. This helps raise awareness about human rights violations. The prize focuses on protecting human rights and freedoms, especially freedom of speech. It also looks at protecting minority rights, following international law, and developing democracy.

European Charlemagne Youth Prize

The European Charlemagne Youth Prize encourages young people to take part in European integration. The European Parliament and the International Charlemagne Prize Foundation give this award to youth projects. These projects aim to build a common European identity and citizenship among young people.

European Citizens' Prize

The European Citizens' Prize is given by the European Parliament. It recognizes activities and actions by citizens and groups that promote unity among EU citizens. It also awards projects that encourage cooperation across EU countries.

LUX Prize

Since 2007, the LUX Prize has been awarded by the European Parliament to films. These films deal with important European topics and encourage thinking about Europe and its future. The Lux Prize has become a respected film award. It supports European films and their production both inside and outside the EU.

Daphne Caruana Galizia Journalism Prize

Since 2021, the Daphne Caruana Galizia Journalism Prize has been awarded by the European Parliament. It recognizes excellent journalism that shows EU values. The prize is 20,000 euros. The first winner was the Pegasus Project in 2021. This award is named after the Maltese journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was killed in Malta in 2017.

See also

In Spanish: Parlamento Europeo para niños

In Spanish: Parlamento Europeo para niños

- Parlamentarium

- State of the Union address (European Union)

- Rules of Procedure of the European Parliament

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |