European Coal and Steel Community facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

European Coal and Steel Community

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952–2002¹ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

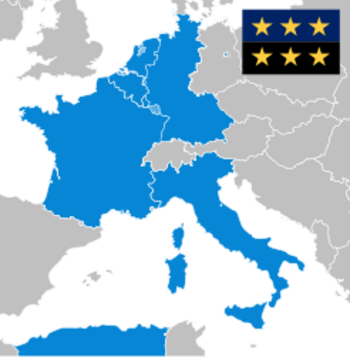

Flag

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Founding members of the ECSC:

Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany (Algeria was an integral part of the French Republic) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | International organization | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Not applicable² | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of the High Authority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1952–1955

|

Jean Monnet | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1955–1958

|

René Mayer | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1958–1959

|

Paul Finet | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Signing (Treaty of Paris)

|

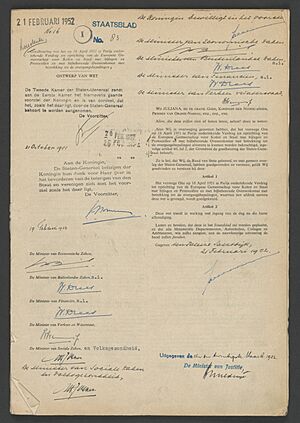

18 April 1951 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• In force

|

23 July 1952 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Merger

|

1 July 1967 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 July 2002¹ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | European Union | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was an international group formed after World War II. Its main goal was to bring together Europe's coal and steel industries. This created a single market where these goods could move freely. The ECSC was based on a new idea called supranationalism. This meant decisions were made by a special group, the High Authority. Its members worked for the good of the whole Community, not just their own countries.

The ECSC was officially started in 1951 by the Treaty of Paris. The founding countries were Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany. It was seen as the first big step towards uniting Europe after the war. Over time, more countries joined, and its responsibilities grew. This eventually led to the creation of the European Union.

The idea for the ECSC came from French foreign minister Robert Schuman on 9 May 1950. This day is now celebrated as Europe Day. Schuman wanted to prevent future wars between France and Germany. He believed that by sharing control of coal and steel production, war would become "not only unthinkable but materially impossible." The Treaty created a common market. This meant no customs duties or taxes on coal and steel between member states. It also stopped unfair business practices.

The ECSC had four main parts to make sure its rules were followed:

- A High Authority (like today's European Commission).

- A Common Assembly (like today's European Parliament).

- A Special Council (like today's Council of the European Union).

- A Court of Justice (like today's Court of Justice of the European Union).

These parts became the model for how the European Union works today.

The ECSC inspired other European groups created in 1957 by the Treaty of Rome. These were the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community. In 1967, the Merger Treaty combined the ECSC's institutions with those of the European Economic Community. The ECSC treaty officially ended on 23 July 2002, after 50 years. Its work was then fully taken over by the European Community, which later became the European Union.

Contents

History of the European Coal and Steel Community

After World War II, Robert Schuman helped change French policy. He moved away from controlling German areas like the Ruhr or the Saar. Despite strong opposition in France, the French Assembly supported his new idea. This was to bring Germany into a European community. The International Authority for the Ruhr also changed because of this.

Schuman's Big Idea: Preventing War

The Schuman Declaration aimed to stop future conflicts between France and Germany. It also sought to prevent wars among other European countries. Schuman suggested creating the ECSC mainly for France and Germany. He said, "Europe needs to unite, and this means ending the old conflict between France and Germany."

Coal and steel were key for making weapons. Schuman proposed that by uniting these industries under a new system, war would be "not only unthinkable but materially impossible." This system also included a European agency to stop cartels (groups of companies that secretly agree on prices).

Negotiating the Treaty of Paris

After the Schuman Declaration in May 1950, talks began on 20 June 1950. These talks led to the Treaty of Paris (1951). The goal was to create a single market for coal and steel among member countries. This meant getting rid of customs duties, special payments, and unfair business practices. A High Authority would oversee this market. It would handle supply and demand issues, collect taxes, and plan production.

A big challenge was breaking up large coal and steel companies in Germany's Ruhr region. These companies, called Konzerne, had supported Germany's military power in the past. Germans saw these companies as key to their economy. The steel owners were very powerful and wanted to keep things as they were.

The United States was not officially part of the talks. However, it played a big role behind the scenes. John J. McCloy, the US High Commissioner for Occupied Germany, wanted to break up these large companies. His advisor, Robert R. Bowie, helped write the treaty's rules against monopolies and cartels. Another US official, Raymond Vernon, also checked every part of the treaty. He stressed how important it was for the common market to be free from unfair practices.

The Americans insisted that the German coal sales monopoly, Deutscher Kohlenverkauf (DKV), be broken up. They also wanted steel companies to stop owning coalmines. The DKV was split into four sales agencies. The steel company Vereinigte Stahlwerke was divided into thirteen firms, and Krupp into two. Ten years later, a US official called these changes "almost revolutionary" for how Europe traditionally handled these industries.

Political Challenges and Treaty Approval

In West Germany, Karl Arnold, the leader of North Rhine-Westphalia (where the Ruhr is), supported a coal and steel community. But the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) opposed the plan. Their leader, Kurt Schumacher, did not trust France or the idea of a "Little Europe of the Six." He thought it would stop German reunification. He also feared the ECSC would lead to a Europe of "cartels, clerics and conservatives." However, younger SPD members supported the idea.

In France, Schuman had strong support from many politicians and thinkers. Even though Charles de Gaulle had supported economic links before, he opposed the ECSC. He called it a "false pooling" because he thought it was a small step towards European unity. He also felt the French government was "too weak" to control the ECSC properly. De Gaulle and his followers voted against the treaty.

Despite these challenges, the ECSC gained much public support. It was approved by large majorities in all eleven parliaments of the six countries. Many people in 1950 believed another war was coming. The ECSC offered a path to peace. The Council of Europe also helped build support for the Community.

The UK Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, did not want Britain to join. He said he would not let the UK economy be controlled by an "undemocratic" authority.

The Treaty of Paris: A New Beginning

The Treaty of Paris (1951), with 100 articles, was signed on 18 April 1951. The "inner six" countries signed it: France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. The ECSC was based on supranational principles. It aimed to grow the economy, create jobs, and improve living standards by creating a common market for coal and steel. This market also aimed to make production more efficient and ensure stability. The common market for coal opened on 10 February 1953, and for steel on 1 May 1953. The ECSC replaced the International Authority for the Ruhr.

On 11 August 1952, the United States was the first country outside the ECSC to recognize it. The US said it would now deal with the ECSC on coal and steel matters. The ECSC then opened its first office outside Europe in Washington, D.C.

Six years after the Treaty of Paris, the same six ECSC members signed the Treaty of Rome. This created the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom). These new groups were similar to the ECSC. Unlike the ECSC treaty, which lasted 50 years, the Treaties of Rome were for an unlimited time. The EEC focused on creating a customs union, and Euratom on nuclear power.

Merging Institutions and the End of the Treaty

Even though the ECSC, EEC, and Euratom were separate, they shared some parts. They all used the Common Assembly and the European Court of Justice. However, their Councils and Commissions were separate. To avoid doing the same work twice, the Merger Treaty combined these separate bodies. The EEC later became a main part of today's European Union.

The Treaty of Paris was changed many times as the European Community and EU grew. As the treaty was set to end in 2002, discussions began in the 1990s. It was decided that the treaty should simply expire. The ECSC's responsibilities were moved to the Treaty of Rome. Its finances and research fund were handled by a special agreement in the Treaty of Nice. The treaty finally ended on 23 July 2002. On that day, the ECSC flag was lowered in Brussels and replaced with the EU flag.

How the ECSC Was Organized

The ECSC had four main parts: the High Authority, the Common Assembly, the Special Council of Ministers, and the Court of Justice. There was also a Consultative Committee. This committee represented producers, workers, consumers, and dealers. These groups merged in 1967 with those of the European Community. The Consultative Committee stayed separate until the treaty ended in 2002.

The treaty said that the location of these groups would be decided by all members. This was a big debate. For a while, they were in Luxembourg, and the Assembly met in Strasbourg.

The High Authority: The ECSC's Executive Body

The High Authority was like the European Commission today. It was the main executive body that ran the ECSC. It had nine members, each serving for six years. The governments of the six founding countries appointed them. France, Germany, and Italy each had two members. Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands each had one. These members then chose one person to be the President of the High Authority.

Even though national governments appointed them, the members promised to work for the whole Community. They swore to not represent their own country's interests. To ensure fairness, members could not have other jobs or business interests while serving. Also, one-third of the members were replaced every two years.

The High Authority had wide powers to make sure the treaty's goals were met. It also ensured the common market worked well. The High Authority could issue three types of rules:

- Decisions: These were fully binding laws.

- Recommendations: These set binding goals, but countries could choose how to reach them.

- Opinions: These had no legal power.

Before the merger in 1967, the High Authority had five Presidents. There was also an interim President for the final days.

Other Important ECSC Groups

The Common Assembly was the first version of the European Parliament. It had 78 representatives. France, Germany, and Italy each had 18. Belgium and the Netherlands each had 10. Luxembourg had 4. This Assembly watched over the High Authority. Its members were usually national Members of Parliament. They were sent to the Assembly each year. The treaty called them "representatives of the peoples" to show they were not just government representatives. The Assembly was meant to be a democratic check on the High Authority. It could advise and even remove the Authority. The first President was Paul-Henri Spaak.

The Special Council of Ministers was the first version of the Council of the European Union. It was made up of representatives from national governments. Each country took turns being in charge for three months, in alphabetical order. A key job of the Council was to make sure the High Authority and national governments worked together. The Council also had to give its opinion on some of the High Authority's work. For issues only about coal and steel, the High Authority had full power. But for other areas, the Council's agreement was needed.

The Court of Justice made sure ECSC law was followed. It also explained and applied the Treaty. The Court had seven judges. National governments chose them for six-year terms. The judges did not have to be from a specific country. They just needed to be qualified and clearly independent. Two Advocates General helped the Court.

The Consultative Committee was the first version of the Economic and Social Committee. It had between 30 and 51 members. These members were equally divided among producers, workers, consumers, and dealers in coal and steel. There were no limits on how many members could come from each country. The committee's members were chosen for two years. They were not bound by instructions from the groups that appointed them. The High Authority had to ask the committee for advice in some cases and keep it informed. The Consultative Committee remained separate until 2002. Then, its duties were taken over by the Economic and Social Committee.

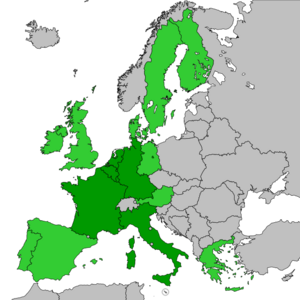

ECSC Member Countries

| Date | Members | Members added |

|---|---|---|

| 23 July 1952 | 6 | The Inner Six: Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands |

| 1 January 1973 | 9 | Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom |

| 1 January 1981 | 10 | Greece |

| 1 January 1986 | 12 | Portugal and Spain |

| 1 January 1995 | 15 | Austria, Finland and Sweden |

After the first six members, the ECSC grew to include all members of the European Economic Community (later called the European Community). By 2002, when the Treaty of Paris ended, there were 15 member countries.

What the ECSC Achieved

Stopping Wars Between Member States

Robert Schuman said the ECSC's goal was to "make war not only unthinkable but materially impossible." This idea is written in the treaty's introduction. It starts by quoting Schuman's proposal: "World peace cannot be protected without new actions that match the dangers threatening it." Europe had been the center of world wars. To prevent this, the Community created the world's first international agency against cartels. The treaty had rules against cartels and trusts. These had helped fuel past arms races and disrupt free markets.

The six founding countries of the ECSC have now had the longest period of peace in over 2000 years of their history.

Economic Impact and Social Benefits

The ECSC's economic goal was to "help economic growth, create jobs, and improve living standards." Some experts say the Community had little effect on coal and steel production. Global trends influenced production more. For example, oil, gas, and electricity became competitors to coal. So, the drop in coal mining was not mainly due to the treaty.

However, the treaty did lower costs by removing unfair railway fees. This greatly increased trade between members. Steel trade, for example, grew tenfold. The High Authority also gave out 280 loans to help industries modernize. This improved output and reduced costs.

Some argue that the ECSC did not fully achieve all its economic goals. For instance, large coal and steel groups, like the Konzerne, reappeared. These groups had helped build Germany's war machine before. Cartels and big companies returned, which seemed to lead to price fixing. Also, the Community did not create a common energy policy. Some also say the ECSC failed to make workers' pay equal across the industry. These issues might have been due to trying to do too much in a short time.

The ECSC's biggest successes were in helping people. Many miners lived in very poor housing. Over 15 years, the ECSC helped fund 112,500 homes for workers. It paid a large amount per home, helping workers buy houses they could not afford otherwise. The ECSC also paid half the costs for workers who lost their jobs when coal and steel factories closed. With aid for regional development, the ECSC spent a lot of money creating about 100,000 jobs. A third of these jobs went to unemployed coal and steel workers. The ECSC's welfare support ideas were copied by some of the six countries for workers in other industries too.

More importantly than creating Europe's first social and regional policy, Robert Schuman believed the ECSC brought peace to Europe. It introduced Europe's first tax. This was a small tax on production, up to one percent. Since European Community countries are now experiencing the longest period of peace in over seventy years, this tax has been called the cheapest tax for peace in history. Another world war was avoided.

See also

In Spanish: Comunidad Europea del Carbón y del Acero para niños

In Spanish: Comunidad Europea del Carbón y del Acero para niños

- Energy Community

- Energy policy of the European Union

- Flag of the European Coal and Steel Community

- History of the European Union

- History of the Ruhr District

- Industrial plans for Germany

- Monnet plan

- Schuman Declaration

- Supranationalism

- Supranational union

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |