Navarrese electoral Carlism during the Restoration facts for kids

Carlism was a very important political movement in Navarre, a region in northern Spain. This happened between the end of the Third Carlist War in 1876 and the start of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship in 1923. After losing the war, the Carlists changed their focus. They stopped fighting and started using political methods, like elections and media campaigns.

They adapted to the political system of the time, which was a monarchy under King Alfonso XII. Carlist leaders saw elections, especially those for the Spanish parliament (called Cortes Generales), as a main way to get their ideas out. Navarre became a strong base for the Carlists. About 35% of all Carlist members of parliament elected during this nearly 50-year period came from Navarre. Even though Carlism was a smaller movement in Spain overall, its strength in Navarre helped it stay active until it became powerful again during the Second Spanish Republic.

Contents

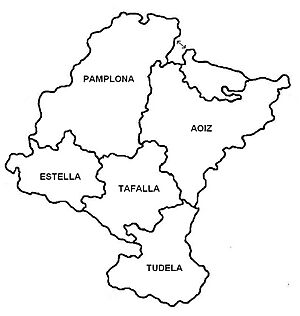

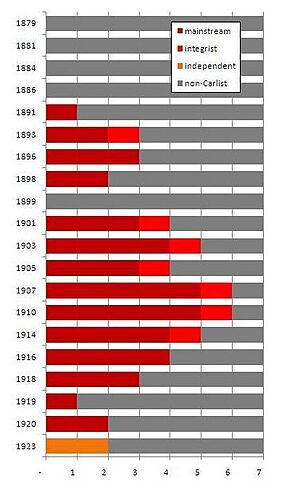

During the time known as the Restoration, Navarre was split into 5 election areas. These areas were similar to the existing legal districts. Four of them (Estella, Aoiz, Tafalla, and Tudela) were "rural districts," each electing one person. The fifth area, Pamplona, was a "constituency" and elected three people. In both types of areas, the person with the most votes won (this is called the first-past-the-post system). In the 1900s, the comarca of Améscoas moved from the Pamplona district to the Estella district.

Before the 1886 elections, only men over 25 who owned a certain amount of property could vote. This was about 19,000 people, or 6% of the population. After the 1891 elections, all men over 25 could vote. This increased the number of potential voters to about 64,000 people, or 21% of the population.

Spanish elections during the Restoration had two main features: `turnismo` and `caciquismo`. `Turnismo` meant that two main parties, the Conservatives and the Liberals, took turns winning elections. They made sure they had a majority in parliament. They did this using many tricks to rig elections, known as `pucherazos`. `Caciquismo` was a system of political corruption. It involved local party bosses, called `caciques`, who controlled votes. In Navarre, both of these systems were used. However, they became less effective over time. Rural areas were usually more affected by election fraud.

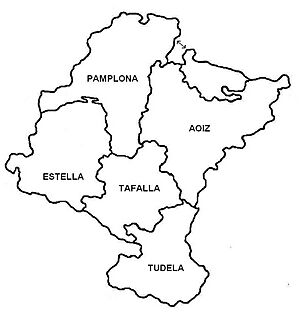

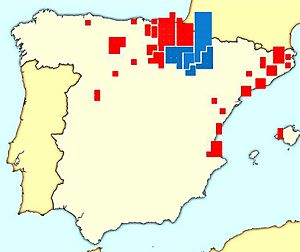

Navarre elected 35% of all Carlist members of parliament (50 out of 144) during the Restoration period. This percentage changed over the nearly 50 years. In the 1880s, Navarre didn't win any seats. Other regions like Guipuzcoa, Álava, and Vizcay sometimes won a few. In the 1890s and from 1916 onwards, Navarrese members made up about 30-40% of all Carlist members. From 1903 to 1914, Navarre was very important for the Carlists. In 1906, a record 67% (4 out of 6) of Carlist members were from Navarre. The most successful years were 1907 and 1910. Carlists won 6 out of 7 possible seats in Navarre. During these times, they made up about 1.5% of all members of parliament in Spain.

No other part of Spain elected as many Carlist members as Navarre. The Basque Country elected 44 members, and Catalonia elected 23. Old Castile and Valencia each elected 11. Five seats were won in Asturias, Leon, and Baleares. Not a single seat was won in the capital city, Madrid.

Pamplona, with 22 MPs, was the Spanish election area with the most Carlist members elected. Estella (12 MPs) was fourth, and Aoiz (8 MPs) was fifth. Tafalla (5 MPs) was also in the top ten. Tudela (3 MPs) was in the middle. The highest success rate, measured by the percentage of seats won, was in two districts in Guipuzcoa. Estella was third (65%), Aoiz was fourth (40%), and Pamplona was sixth (37%).

Carlist Elections Over Time

The Carlist election history in Navarre from 1879 to 1923 can be divided into four periods. Each period had different conditions, strategies, and results. From 1879 to 1890, Carlists had almost no success in elections. From 1891 to 1902, they started to gain power. From 1903 to 1917, Carlists were very strong. Finally, from 1918 to 1923, their power slowly faded.

After their military defeat in 1876, Carlist activities stopped. Their newspapers were shut down, clubs closed, and leaders were sent away. Slowly, the party rebuilt itself. But until the late 1880s, there were no Carlist election centers in Navarre. Their first daily newspaper, El Tradicionalista, appeared in 1886. La Lealtad Navarra followed in 1888. The party didn't officially put forward candidates. However, a few people who liked Carlist ideas ran for office. Carlists first tried their strength in elections for the Navarre regional council in the late 1870s. They were not successful until the late 1880s. They first became a political group in local city elections. In 1881, they elected 8 `concejales` (council members) to the Pamplona city hall (`ayuntamiento`).

From the late 1880s, Carlism became more organized and modern. In 1888, the movement split into mainstream Carlism and Integrism. Both groups became more aggressive. In the 1891 elections, most Carlist candidates lost easily. But the election of Sanz Escartín marked the start of Carlist growth. In 1893, mainstream Carlists won two seats. The Integrists won one. The Liberals also started to decline. In 1896, Carlists won 3 seats. In the 1898 campaign, Carlists might have been too confident. Sanz and Mella won, but Irigaray did not. In 1899, Carlos VII, the Carlist leader, told his followers not to vote. No Carlist candidates ran. In 1901, Carlists won 2 seats in Pamplona and Estella. Irigaray won for the first time in Aoiz.

Between 1903 and 1917, both Carlist groups won 29 out of 42 possible seats (69%). This period clearly showed their power. The only area they didn't fully control was Ribera Baja. In the Tudela district, they won only 2 out of 6 seats. Carlists became very important in Navarre's politics. Other parties often sought their support. In many elections during this time, opponents didn't even try to compete against them. This period ended with the 1916 elections. Carlists changed their alliance strategy to try and win back Tudela and Tafalla districts. They only partly succeeded.

The final phase was from 1918 to 1923. During this time, the Integrists disappeared. Carlists started making tactical alliances, even if it meant changing their clear political ideas. This caused problems within the Carlist movement. This strategy did not work as expected. The `Mellista` split (a group breaking away from Carlism) made things worse. Also, new Basque, republican, and socialist parties grew stronger. This led to Carlism losing votes. In the last election of the Restoration in 1923, Jaime III, the Carlist leader, told people not to vote. He said he was disappointed with the corrupt democracy. Only 2 out of 4 Carlist-related candidates who ran on their own were elected.

What Carlists Believed In

At first, Carlists did not focus on a strong, idea-driven political program. Instead, their message was that only Carlism truly represented the local interests of Navarre in Madrid. They emphasized the "Fueros" part of their beliefs. Fueros were special laws and rights that Navarre had. Protecting these local interests was always a key part of the Carlists' election campaigns in Navarre. However, even when they called for the return of the old laws from before 1841, they never fully supported the idea of Navarre or the broader Basque-Navarrese region becoming fully independent. This issue was a difficult one during the Alianza Foral in the 1920s. It caused problems between Carlists and Nationalists and even led to divisions within Carlism itself.

Another common part of the Carlist message was about Christian values. Mainstream Carlists competed with other right-wing groups, especially the Integrists, to get support from Catholic church leaders. If they couldn't get direct support, they at least wanted their Catholic beliefs to be confirmed. After the Catholic Congress of Zaragoza in 1890, all candidates running as "Catholics" tried to get approval from bishops. Carlists wanted this approval only for themselves. They criticized bishops for giving this approval to Liberal candidates too.

In the 1900s, Carlist messages increasingly attacked political corruption. They said corruption was an unavoidable result of liberalism. They even criticized the election system itself. Another growing idea was the defense of `legitimism`. This meant supporting the traditional royal family. However, they usually hinted at their claims to the throne instead of openly challenging the current king. Carlist candidates' campaigns were always very conservative and against democracy. Around the turn of the century, they became even more extreme. They often called for defending traditional values against a "red revolution." In the late 1910s and early 1920s, Carlists made many tactical alliances. This meant they put their ideas aside. The Integrists strongly criticized the `Jaimistas` (mainstream Carlists) for allying with their old enemies, the Liberals. In the last years of the Restoration, Carlists openly rejected the political system, calling it a "parliamentary farce."

Who Were Carlist Friends and Foes?

Carlists in Navarre did not have a single, clear, and continuous alliance policy during elections. Their choices of friends and enemies depended on what was happening within Carlism in Spain. It also depended on the decisions of the Carlist leaders, local situations, and events in Navarre and Spain.

In the 1880s and most of the following decades, the Liberals were the Carlists' main enemies. The Liberals had won the wars. Carlists did not put forward their own candidates. Instead, they supported some candidates from other groups. One such group was the Conservatives. The most famous Conservative was Marqués de Vadillo. He was seen as a semi-Carlist candidate. His network of local bosses was sometimes called `carlo-vadillismo`. Other friendly candidates were the Fueristas. This group focused on Navarre's special laws (`fueros`) and Catholic ideas. As the Carlist organization rebuilt, the Fueristas' supporters gradually joined the Carlists in the late 1880s.

In 1888, the Integrists, led by Ramón Nocedal, broke away from mainstream Carlism. This caused a bitter rivalry between the two groups. At first, in Navarre, they thought about supporting each other's candidates. But in 1891, they ran against each other. In the 1890s, both groups saw each other as their main enemy and fought fiercely. When the Integrists didn't have a candidate (like in 1898), they refused to support any Carlist. They even supported Carlist opponents. The hostility changed in early 1899. The two groups agreed to work together in Guipuzcoa. This Carlist-Integrist alliance soon spread to Navarre. In 1899, both groups boycotted the elections. In later campaigns, they worked together.

From the early 1900s, Carlists became very influential in Navarre's politics. Other parties competed to get their support. The most stable alliances were with the Integrists and then the `Mauristas` (supporters of Antonio Maura). These alliances were usually formed under a broad umbrella of monarchist, Catholic, and regional ideas. As part of these deals, the three Pamplona seats were shared. One went to a Carlist, one to an Integrist, and one to a Conservative. Carlist allies also had the advantage of a "second vote."

Around 1915, the Carlist alliance policy began to change. This was due to complex negotiations in local elections. In 1916, Carlists changed their strategy. They preferred Liberals over Integrists as allies to win back the Tudela and Tafalla districts. This year also marked a new strategy of making tactical alliances. This meant they sometimes put their clear political ideas aside. One alliance that angered many was with the Liberals. An agreement with the Nationalists, first meant for local elections but later used in general elections, also surprised many. Finally, the `Mellista` split divided Carlism even more.

Looking at where Carlism was supported in Navarre shows some general patterns. These patterns were true for most of the Restoration period. However, there were some changes in specific parts of the region. In general, Carlism had the most success in the Estella election district. They won 60% of the available seats there. Aoiz was next (40%), then Pamplona (37%), Tafalla (25%), and Tudela (15%).

Carlism was most popular in the central part of Navarre. This area included the Western Sierras, Tierra Estella, Pamplona Basin, Central Navarre, Lower Mountain, and parts of the Pre-Pyrenees. The main Carlist area was where the Pamplona, Estella, and Tafalla districts met. This was around Artajona, Mendigorría, Larraga, Val de Mañeru, and Valdizarbe. A big change in this central area was that Carlist votes slowly decreased at the southern edge of this belt. This happened in Ribera Estellesa, the northern towns of Ribera Arga, and in Sierra de Ujué.

The city of Pamplona was controlled by Carlists in the early 1890s. But by the end of the century, their rivals caught up. Sanz was no longer the most popular member of parliament in the city. Later in the 1900s, de Mella also lost first place to a `Maurista` candidate. This trend continued. At some point, Carlism lost its hold on the capital. In 1931, Pamplona was one of the few places in Navarre where the Carlist-Nationalist alliance lost to the Left. The city of Estella saw the opposite. Carlists first lost badly there. But they won the city in the early 1900s. They kept winning even during the overall democratic victory of 1931.

The northern part of Navarre (Cantabrian Valleys, Southern Valleys, Pre-Cantabrian, Pirineos) was always less enthusiastic about Carlism. Until the late 1890s, the movement did not do well in the mountains. In the Eastern Pyrenees, controlled by the Gayarre family from Valle de Roncal, Carlists didn't even bother to put forward a candidate. Over time, they gained strength in the Southern Valleys, and partly in the Pre-Pyrenees and Eastern Pyrenees. However, their control was not strong. Corredor del Araquil, which supported Carlism in the 1890s, was later won by democrats. The Cantabrian Valleys remained an Integrist stronghold. But over time, the Nationalists gained power there. In general, Carlists did not control the northern belt until the end of the Restoration. The low population density of this hilly region actually helped them when votes were counted in the Pamplona and Aoiz districts.

The area that changed most in its political preferences was the southern part of Navarre. This included Ribera Alta, Ribera Arga, Ribera Aragón, Bardenas Reales, and Ribera Baja. Towns along the Upper Ebro river started to turn away from Carlism in the late 1890s. The southern towns of Estella and Tafalla districts, Ribera Arga, and Ribera Aragón, including the cities of Olite and Tafalla, were usually not very keen on Carlism. The only exception was around 1910, when Bartolomé Feliu Pérez briefly changed this pattern. Towns along the Lower Ebro did not show clear preferences until the 1910s. However, in Ribera Baja, Carlism kept its isolated stronghold in the capital, Tudela, for decades. They lost the city after 1910 and couldn't win it back. From then on, the entire Eastern Ribera area slowly slipped into the hands of Carlist enemies, mostly Republicans and Socialists.

Important Carlist People

Twenty people were elected as Carlist members of parliament from Navarre during the Restoration. Many others ran but never won. Two people stood out: Joaquín Lloréns Fernández and Juan Vázquez de Mella. They were not from Navarre but served 8 terms each as Navarrese members of parliament.

Joaquín Lloréns Fernández (1854-1930) was from the Levante region and was a soldier. He led the Carlist artillery during the Third Carlist War. He started his parliamentary career elsewhere. But from 1901, he was elected 8 times in a row from Estella. He was so dominant in that district that no one dared to run against him from 1910 to 1916. However, he was defeated in Estella in 1919. Juan Vázquez de Mella (1861-1928) was from Asturias and was a leading Carlist thinker. He served 8 terms as a Navarrese member of parliament. He was elected 7 times (3 times from Estella and 4 times from Pamplona). In 1903, he replaced another successful candidate, Miguel Irigaray. Both of them became very involved in local issues over time.

The most notable local member of parliament was Romualdo Cesáreo Sanz Escartin. He was a Carlist general from Pamplona. He was the first Carlist member of parliament elected in Navarre during the Restoration. He won 5 times in his home city and later served in the Senate. The most elected Integrist candidate was José Sánchez Marco. He represented Pamplona in 1907, 1910, and 1914. Other Integrists elected were Ramón Nocedal and Arturo Campión. The only person elected as an independent Carlist was Justo Garrán Mosso. He ran when both the `Jaimistas` (mainstream Carlists) and Integrists did not put forward official candidates. Two national Carlist leaders ran in Navarre: Bartolomé Feliu Pérez in 1910 and Luis Hernando de Larramendi in 1920. There were also local Navarrese leaders who ran, like Simón Montoya Ortigosa (who lost) in the 1890s, or Gabino Martínez Lope García (who won) in the 1910s. The two `condes de Rodezno` (counts of Rodezno) were the only example of two generations, father and son, serving as Carlist Navarrese members of parliament.

The candidate who received the most votes was de Mella in 1907 (13,341 votes) and in 1914 (11,338 votes). Sanchez Marco also got over 10,000 votes in 1907 (10,166 votes), and Sanz in 1891 (10,003 votes). These high numbers were in the Pamplona district because it was a large election area. In terms of the percentage of votes won, Llorens Fernandez was first. He was supported by 99.51% of voters in Estella in 1907. In total, there were 8 times when Carlists won without anyone running against them (this was allowed by Article 29 of the law). This happened to Lloréns from Estella in 1910, 1914, and 1916. It also happened to Tomás Domínguez Romera from Aoiz in 1914. Vázquez de Mella and Sanchez Marco in 1910, Víctor Pradera in 1918, and Joaquín Baleztena in 1920 (all from Pamplona) also won this way.

Why Carlism Was Popular

Many theories try to explain why Carlism was popular (or not). Some scholars focus on social and economic conditions, but they might have different ideas. The most common theory says that Carlism did well in rural areas. These areas had large shared lands and many medium-sized farms. These farms were at least self-sufficient and often sold their products. This type of farming provided a good economic base for peasant owners, who were the main supporters of Carlism. This was common in northern Spain, especially in most of Navarre. When this group of people was replaced by owners of small, unsustainable plots, landless peasants, tenants, or day laborers, Carlism lost its support. This happened in the Navarrese Ribera, where many large landowners lived. In the Pyrenees, at the other end of Navarre, poor soil and short growing seasons made medium-sized farms less efficient. This led to land shortages and problems, which were partly eased by people moving away. If rural areas became industrialized, the resulting social changes weakened traditional ways of life and reduced Carlist popularity. This is thought to have happened in Corredor del Araquil.

Another set of reasons for Carlist popularity relates to culture and religion. Carlism was strongly connected to religious belief, which was strongest in the northern provinces. A strong network of local churches, mostly served by priests from the same area, helped support the movement. Groups of people who were not very religious or were openly against religion, like middle-class professionals in cities, are thought to be responsible for Carlism's lower popularity in urban areas. This even led to Carlism having an anti-urban feeling. The influence of people who had lived abroad or returned, combined with direct experience of the secular French state across the Pyrenees, is suggested as a reason for Carlism's weaker hold on the mountainous towns.

One of the most debated topics is the connection between Carlism and Basque nationalism. It is clear that for a while, Carlism and Basque identity supported each other. This helps explain why Carlism had limited support in the southeastern part of Navarre. The main discussion is about when the two started to separate. Also, how much Basque nationalism got its characteristics from Carlism, and how much Carlism declined because its voters were taken over by Basque parties.

In recent decades, historians studying Carlism have become more doubtful about putting socio-economic conditions first. They now suspect this approach is too simple. One reviewer points out that new studies focus on "microsystems of daily life." These include things like shared ways of thinking, religious and moral values, cultural factors, customs, and family interactions. Another historian asks if this new wave of studies means a return to politics as the main way to understand things. This new approach has yet to fully explain the patterns of Carlist election results in Navarre.

See also

In Spanish: Carlismo electoral navarro (Restauración) para niños

In Spanish: Carlismo electoral navarro (Restauración) para niños

- Electoral Carlism (Restoration)

- Carlism

- Integrism (Spain)

- Restoration

- José Sánchez Marco

- Joaquin Llorens Fernandez de Cordoba

- Ramón Nocedal Romea

- Tomas Dominguez Arevalo

- Joaquin Baleztena Ascarate

- Juan Vázquez de Mella

Images for kids

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |