Mellismo facts for kids

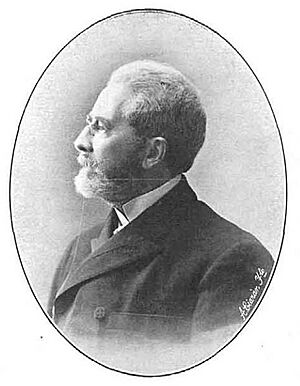

Mellismo was a political idea in Spain in the early 1900s. It was a very conservative, or "ultra-Right," movement. This idea was created and led by Juan Vázquez de Mella. He was a powerful speaker and politician.

Mellismo started within a group called Carlism. Carlism wanted a traditional monarchy for Spain. Vázquez de Mella wanted to build a big, strong ultra-Right party. This party would change Spain from a liberal democracy to a traditional, corporative monarchy. A corporative system means different groups (like workers or businesses) would have a say in government.

After 1919, Vázquez de Mella and his followers left Carlism. They formed their own party called the Partido Católico Tradicionalista. However, this party did not succeed in uniting all the right-wing groups. It soon fell apart. People who followed Mellismo were called Mellistas.

Contents

The Start of Mellismo (1900–1912)

Historians usually don't use the term "Mellismo" before 1910. Newspapers started using it around 1919. In the early 1900s, people talked about different groups within Carlism. Some were called "posibilistas" because they wanted alliances with other parties. Others were "cerralbistas," supporting a leader named Marqués de Cerralbo. Vázquez de Mella saw himself as a "cerralbista."

Mella started gaining followers in the 1890s. People liked his strong speaking skills. His ideas were a bit confusing at first. He was against the current government system. But he also worked with existing parties. He took part in elections. Yet, he also planned a military takeover around 1898–1900. He wanted big changes but made small alliances.

After some small Carlist revolts in 1900, Mella had to hide in Portugal. He returned to politics in 1905. Many Carlist leaders were older. Vázquez de Mella became a dynamic and charismatic leader. He was seen as a key thinker for Carlism. He gave powerful speeches in parliament and at public events. He did not hold many official party jobs. But he worked for the Carlist newspaper, El Correo Español.

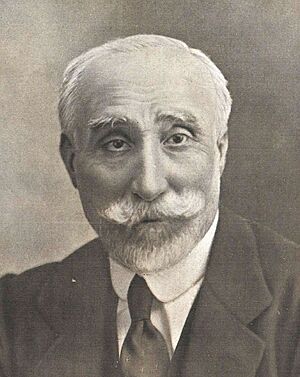

Mella's growing influence became a problem for the Carlist king, Carlos VII. It also troubled the party leader, Matías Barrio y Mier. Carlos VII wanted careful alliances for elections. He tried to limit Mella's power in the newspaper. In 1909, Carlos VII chose Bartolomé Feliú as the new leader. This was a surprise to Mella's supporters. They thought Mella should be the leader.

When Carlos VII died, his son Jaime III became the new Carlist king. Mella's supporters wanted Feliú removed. Don Jaime made a deal. He kept Feliú but made Mella his personal secretary. After a few months in 1910, Mella became unhappy with the new king. The feeling was mutual.

During the 1910 elections, Mellismo first appeared as a clear strategy. Feliú wanted alliances based on Carlist claims. But Vázquez de Mella formed a strong conservative alliance. He worked with Antonio Maura and his Conservative Party. For the next two years, Mellistas worked against Feliú. They said he was not a good leader. They avoided talking about alliances. In 1912, Mella demanded Feliú's removal. Don Jaime agreed. He put de Cerralbo back in charge by the end of 1912.

Mellismo in Action (1912–1919)

Some historians believe Vázquez de Mella took control of the Carlist party. De Cerralbo was getting older and less decisive. Mella's ideas, Mellismo, shaped Carlist policy. Mella strongly influenced the Carlist members of parliament. Nearly half of them were Mellistas. Others often agreed with him.

In the party's top group, the Junta Superior, about one-third of the members supported Mellismo. This included leaders from regions like the Basque Country, Catalonia, and Valencia. When de Cerralbo reorganized the party, Mella took charge of propaganda and press. Other Mellistas led sections for elections and organization. The newspaper El Correo Español became more and more controlled by Mellistas.

During World War I, Don Jaime was hard to reach in Austria. The Mellistas took almost full control of the party. Their strategy was clear in the Carlist election campaigns of 1914, 1916, and 1918. The Spanish political system was starting to break down. Fewer people were voting. The two main parties were splitting.

Mella wanted a small alliance of right-wing groups. This would lead to a big, powerful ultra-Right party. This new party would get rid of liberal democracy. It would create a traditional, corporative system. The question of who should be king was not important for this plan. In 1914, local Carlist leaders could make their own alliances. But Vázquez de Mella and Maura worked to form Carlist-Maurist agreements.

In the 1916 campaign, Vázquez de Mella openly spoke about uniting the "extreme right." New terms like "mauro-mellistas" were used. Maura also hinted at changing the public system. However, this strategy had limits. Alliances ended after elections. Carlist candidates still won only about 10 seats. This was not a big improvement. Also, some party members worried that local traditions would be lost in a big alliance.

When World War I started, Mella's pro-German feelings grew stronger. His speeches and writings supported Spanish neutrality. But they also favored the Central Powers (like Germany) and were against Britain. After 1916, many people in Spain started to favor the Allies. Mellistas then focused on keeping Spain from joining the Allies.

The Carlist king, Don Jaime, was in Austria during most of the war. He was unclear about his stance. Officially, he supported neutrality. But privately, he leaned towards the Allies. He did not stop the Mellistas from expressing pro-German views. Historians have different ideas about how World War I related to Mellismo. Most think it came from Mellismo's core ideas. They praised Germany's anti-liberal government. They criticized the democratic systems of Britain and France. Some think a Central Powers victory would help the extreme Right take over in Spain. Others believe the war issue was not important at all.

The 1919 Breakup

By 1918, Mellismo seemed to be losing strength. Election alliances did not bring big gains. The war's outcome made the pro-German stance less useful. Some regional leaders disagreed with Mella. De Cerralbo, tired of his divided loyalty, finally resigned. Another Mellista, Cesáreo Sanz Escartín, temporarily replaced him.

In early 1919, Don Jaime was released from house arrest in Austria. He arrived in Paris. After two years of silence, he published two statements. These were printed in Correo Español in February. They clearly criticized unnamed Carlist leaders for not staying neutral. They also said the party's leadership would be reorganized.

The Mellistas realized their old strategy would not work. They had tried to force the king to agree with them. Now, a big fight was coming. They launched a media campaign against Don Jaime. They accused him of losing his right to rule. They said he had been passive for years. They claimed he was a hypocrite about neutrality. They also said he ignored traditional Carlist rules. They called his actions a "Jaimada," meaning a coup against Traditionalism. Neither side talked about their different political strategies.

At first, both sides seemed equally strong. But Don Jaime quickly gained the upper hand. His supporters took back control of El Correo Español. He replaced San Escartín with loyal politicians. Many party members who had been unsure about Don Jaime now supported him. Vázquez de Mella called for a big meeting. He still spoke about Carlism and Traditionalism. But some historians believe he already knew he had to leave the Carlist party. They think he wanted to build a new party.

The conflict lasted only two weeks. By the end of February 1919, the Mellistas decided to form their own group. They set up the Centro de Acción Tradicionalista in Madrid as their temporary base.

Many Carlist politicians became Mellistas. These included Vázquez de Mella himself. Other important figures were Luis Garcia Guijarro, Dalmacio Iglesias Garcia, and Víctor Pradera Larumbe. Key regional leaders also joined Mella. These included Tirso de Olazábal from the Basque Country and Teodoro de Mas from Catalonia. Two well-known journalists, Miguel Fernández and Claro Abánades Lopez, also joined. Most of the Mellistas came from the Basque Country and Catalonia.

Some Carlist newspapers supported Mella. But the most important ones, like El Correo Español, stayed loyal to Don Jaime. The split had less impact on the regular Carlist members. In areas where Carlism was small, the split caused confusion. But in strong Carlist regions, like Navarre and Catalonia, most members stayed with Carlism.

New Plans and Problems (1919–1922)

In 1919, the Mellistas worked to build their new movement. They set up local Centros de Acción Tradicionalista across Spain. In Madrid, they started a national newspaper called El Pensamiento Español. They also tried to create a youth group.

Mella refused a job in a new government. He said he could not support the 1876 Spanish constitution. In May, Mellismo became the Centro Católico Tradicionalista (CCT). This was before the 1919 elections. The CCT was meant to be a step towards a big ultra-Right alliance. This alliance would be led by the Traditionalists.

The CCT was no longer tied to the Carlist royal family. It also rejected the Alfonsist monarchy, which it saw as too liberal. The CCT tried to use a Catholic platform to attract other right-wing groups. These included followers of Maura and other conservatives. They also considered alliances with other Catholic and monarchist groups. However, the 1919 elections only brought 4 seats for the Mellistas. Mella himself did not win a seat.

From summer 1919, Mellistas planned a big national meeting. This meeting would launch a new party. They thought about naming it "Católico Nacional." But it became the Partido Católico-Tradicionalista. Regional Mellista meetings were held in Biscay (August 1919) and Catalonia (April 1920).

However, the 1920 election campaign showed problems. Different right-wing groups were willing to make temporary deals. But none wanted to join a new, unified ultra-Right party. Different Mellista leaders started making their own alliances. Some, like Pradera, talked with Maura's group. Others talked with different conservative or Catholic groups. The 1920 elections resulted in only 2 seats for the Mellistas. Vázquez de Mella lost again. He then tried to get a seat in the Supreme Court but failed.

By late 1920, Mellismo was stuck. It was not gaining power. It was also split by two different strategies. Vázquez de Mella still wanted a big extreme-Right group. This group would follow his Traditionalist ideas. But Pradera wanted a simpler alliance. He thought they should unite based on basic conservative Catholic ideas.

Also, Vázquez de Mella wanted to be outside the government system. He would only support a government from the outside. Pradera, however, was willing to work within the existing system. He was ready to take government jobs. Mellismo suffered another setback when many followers joined a new party called Partido Social Popular. In 1921, Vázquez de Mella was unsure about starting his own party. He seemed to think about being a thinker and guide, not a politician.

The End of Mellismo (1922 and After)

The long-awaited big Mellist meeting finally happened in October 1922 in Zaragoza. But it was not what Vázquez de Mella had planned. Many Mellistas who left Don Jaime had already joined other political groups. Others had lost hope after two failed elections. They were also disappointed that the movement seemed lost. Vázquez de Mella himself did not attend the meeting.

Instead, he sent a letter. It was like his last political message. He repeated his anti-system views. He confirmed that a Traditionalist monarchy was the final goal. He said he would work towards it as a thinker, not as a politician. The leaders at the meeting politely said they hoped Mella would change his mind. The meeting ended with a decision to create a new Catholic party.

The Zaragoza meeting was basically the end of Mellismo. Even though two candidates won seats in the 1923 elections under the Catholic-Traditionalist name, the movement was fading. In the year after the Zaragoza meeting, more of Mella's followers joined other political groups.

In 1923, national politics stopped when Miguel Primo de Rivera became dictator. All political groups were dissolved. The Partido Católico-Tradicionalista also ended. Some Mellistas worked in Primo de Rivera's government. A few got high positions. Pradera even became a famous figure in the dictatorship. But historians disagree if this work had anything to do with Mellismo. Some say Mellistas, led by Pradera, joined the Spanish Patriotic Union and made peace with the Alfonsine monarchy. Others believe Mellismo ended as a political group. They call these later groups "seudotradicionalismo" or "mellistas praderistas." They say these groups had little to do with Mella's original ideas.

Vázquez de Mella retired from public life. His last public appearance was in 1924. He died in 1928. In 1931-1932, many of his former followers rejoined the main Carlist group, Comunión Tradicionalista. Some historians still use the term "Mellists" for this time. But others prefer "post-mellistas." Within the Carlist group, the former Mellistas did not form a clear faction. However, some historians say that old Mellist-Jaimist divisions appeared again during the Second Spanish Republic and the Spanish Civil War.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Mellismo para niños

In Spanish: Mellismo para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |