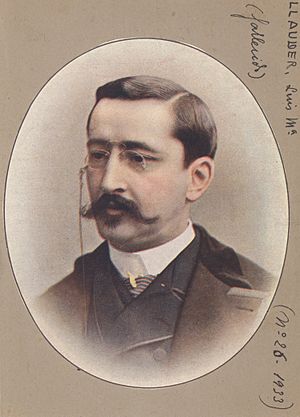

Luis María de Llauder y de Dalmases facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Luis M. de Llauder y Dalmases

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Luis Llauder Dalmases

1837 |

| Died | 1902 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | publisher |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | Carlism |

Luis Gonzaga María Antonio Carlos Ramón Miguel de Llauder y de Dalmases (1837–1902) was a Spanish Catholic publisher and a Carlist politician. He was known as a leader of Carlism in Catalonia in the late 1800s. He also started important Catholic media projects in Barcelona. These included a publishing house, a daily newspaper called Correo Catalán, and a weekly magazine called La Hormiga de Oro.

Contents

Early Life and Family

The Llauder family was first known in the late 1400s as blacksmiths in Argentona, Catalonia. Over time, they became wealthy and owned land in Mataró and Barcelona. In the late 1700s, they built a famous mansion in Mataró called Torre Llauder.

Luis's great-grandfather, José Antonio Llauder y Duran, started a business using water springs. His son, José Francisco Llauder y Camín, continued this business. By 1824, he was the top taxpayer in Mataró, showing how successful the family was.

Luis's father, Ramón de Llauder y Freixes (1807–1870), inherited the family's wealth. He married María Mercedes de Dalmases y de Bufalà (died 1885), who came from a rich family in Catalonia. They married in 1837 and lived in Madrid for a short time before moving to Barcelona. Ramón was a lawyer and a judge. He was also a very religious Catholic who gave a lot of money to the Church. He helped start a school for poor children, a charity Luis also supported.

Luis was one of six children, and all his sisters became nuns. We don't know much about his early schooling. He studied law at the Universitat de Barcelona and finished in 1858. Some say he also studied engineering. He never married or had children.

Getting Involved in Public Life

Luis Llauder was active in Catholic groups in the 1860s. He cared about social issues and charity, just like his father. In 1863, he worked with a charity in Barcelona that focused on education. He also helped organize an agricultural fair in Mataró in 1865.

It's not clear when Llauder started his career as a publisher and journalist. Some say he began writing for local newspapers soon after college. He wrote for Catholic magazines like La Sociedad Católica in the late 1860s. At this time, he was known as a strong Catholic writer.

His political career really began after the Glorious Revolution of 1868. This event led to the First Spanish Republic.

Llauder's family was not known for supporting Carlism. His uncle was even against the Carlists. However, Llauder became a Carlist. In 1869, he wrote a book called El desenlace de la revolución españoIa. In this book, he argued that Traditionalism was the best way for Spain, with the Carlist leader Carlos VII as king. He believed this was the only path based on Catholic ideas. The book did not support violence, a view Llauder held throughout his life. He later said this book was the first time someone openly supported Carlism in Catalonia during that period.

Carlism and the Third Carlist War

Llauder's book made him well-known in Catalonia. He joined the Catholic-Monarchist Association, a group that brought together different right-wing groups. He was seen as a Carlist. In 1870, he was elected to the Spanish parliament (Cortes) for the Carlist party. He was re-elected in 1871.

Around 1870, Llauder started a newspaper in Barcelona called La Convicción with his own money. He was also its main editor. The paper supported Traditionalist ideas. Llauder tried to unite different opposition groups, even some radical republicans, which surprised some people. He was already considered a "prestigious journalist."

Before the Third Carlist War began, Llauder was an important Carlist leader in Barcelona. He lived between Spain and Switzerland, where he was with the Carlist leader Carlos VII. When the war started, he stayed out of Spain because he was a well-known writer and feared for his safety. He did not fight in the war. After the Carlists lost the war, Llauder did not return to Spain right away. He spent some time in Rome, possibly as a Carlist representative to the Vatican.

Becoming an Integrist

When Llauder returned to Spain, he continued his work with the Carlists. He followed the ideas of Cándido Nocedal, who wanted the party to focus on religious issues and strongly oppose the new government. Llauder became a top supporter of Nocedal's ideas in Catalonia, which were known as Integrism.

Integrists believed Carlism should be spread through many publications. In 1875, Nocedal started a newspaper in Madrid called El Siglo Futuro. Llauder did the same in Barcelona. In 1878, he took over Correo Catalán. This newspaper became the main Integrist voice in Catalonia. It published articles from strong Catholic writers and fought against other Carlist newspapers that had different views. Llauder's strong opinions sometimes got him into trouble, leading to legal action and even jail time.

Llauder expanded his publishing work. In 1883, he started a Catholic weekly magazine. In 1885, he opened a bookstore. In 1887, he started a publishing house. All of these were named La Hormiga de Oro (The Golden Ant).

By the mid-1880s, Llauder was fully committed to the Integrist ideas. He believed in strong Catholicism, staying out of the government's politics, and seeing Carlism as a way to unite people through religion. He proudly called himself an Integrist.

The Split of 1888

In early 1888, the Carlist leader Carlos VII asked Llauder to write something that would explain the king's official position. This was a surprising choice because Llauder was a strong supporter of Nocedal, whose son, Ramón Nocedal, wanted to limit the king's power. Some historians think Carlos VII chose Llauder to be a mediator between the different groups. Others believe the king wanted to pull Llauder away from the Nocedalistas.

Llauder wrote an article in Correo Catalán in March 1888 called El Pensamiento del Duque de Madrid (The Thought of the Duke of Madrid). It was written like an interview with the king. The article called for moderation and respect among Traditionalists. It also said that no single newspaper could speak for the king.

Instead of bringing people together, this article caused a bigger split. Nocedal and his supporters left Carlism and formed their own party. Most Carlist newspapers sided with the Nocedalistas. Llauder's decision surprised everyone: after supporting Nocedal for 10 years, he chose to stay loyal to the king.

Llauder's main reason seemed to be his loyalty to the Carlist royal family. The Nocedalistas called him a traitor. Llauder argued that the conflict was due to Nocedal's personal ambitions, not big differences in ideas.

Since the Nocedalistas controlled El Siglo Futuro, which was the main Carlist newspaper, Carlos VII decided to start a new official Carlist newspaper. He gave this job to Llauder. In 1888–1889, Llauder moved to Madrid to start El Correo Español. It was similar to Correo Catalán. After successfully launching it, Llauder gave ownership to the king and moved back to Barcelona in 1889.

Leader in Catalonia

The new Carlist party leader, the Marquis de Cerralbo, wanted to build a stronger organization. In 1889, Llauder was chosen to lead the Carlist group in Catalonia. Even though some people remembered his past actions, Llauder was confirmed as the head of the new official Carlist group in Catalonia in 1890.

In Catalonia, Llauder helped change Carlism from a loose movement into a modern and organized party. He worked to set up local groups. He was very effective: by 1892, Catalonia had 43 Carlist clubs out of 102 in Spain. By 1896, this number grew to 100 out of 298. The Barcelona province had the most clubs. The first youth section of the party was created in Barcelona in 1894.

Llauder generally did not believe in parliament or elections, seeing them as fake. However, he did get involved in Carlist election efforts. He ran in his old area of Berga and won in 1891 but lost in 1893. In 1896, he won a seat in the Senate from Girona. But he refused to take the oath of office, following the king's orders.

During his 14 years leading Carlism in Catalonia, Llauder became one of the most important party figures of the late 1800s. He helped the party recover from the Nocedalista split. He also worked with the party leader to promote a new, peaceful strategy. His health started to get worse around 1898, and he spent a lot of time resting. In 1898, the king made him the Marquis of Vallteix.

Publisher and Author

Llauder owned and edited several newspapers, but he is best known for his work with Correo Catalán and La Hormiga de Oro. Both of these publications lasted for more than 50 years, even after his death.

Llauder took over Correo Catalán in 1878. It was his private property, not owned by the party. He was also its chief editor. The newspaper followed a strong Catholic line. It served as a semi-official party paper in Catalonia, publishing party orders and spreading its message. It had news, opinion pieces, and many religious articles. The newspaper also had weekly versions in other cities. Its circulation was estimated to be between 4,000 and 8,000 copies. Llauder was known for his Sunday editorials.

La Hormiga de Oro, launched in 1884, was a new kind of magazine in Spain. It was large and combined text with high-quality pictures, first drawings and later photographs. It aimed to be a popular educational encyclopedia. It covered news, history, arts, and politics, but mostly focused on religious topics. Its goal was to spread Christian ideas using modern media that people could afford. Carlism was present but not the main focus. It was distributed in Spain, Portugal, the Philippines, and Latin America. It had about 4,000 subscribers and was one of the most widely read magazines in Spain in the early 1900s.

The publishing house La Hormiga de Oro, founded in 1887, was the engine behind Llauder's publications. It also had a dedicated bookstore. This showed that Llauder understood the importance of mass media. It seems that the Llauder family's wealth, built up over nine generations, was used to support Carlist propaganda in Catalonia.

Llauder wrote for different newspapers from the mid-1860s until the early 1900s. Most of his writings were editorials for Correo Catalán. Between 1888 and 1900, he published 537 of them. They were written in Spanish and covered many topics, serving as semi-official Carlist teachings. While not a political theorist, his writings are seen as a collection of Carlist ideas.

Llauder's writings were deeply Catholic. Some called his work "secular evangelization" and him a "priest of the cause." He saw the world as a battle between God and evil. He strongly opposed liberal Catholicism. He often interpreted events, like the cholera threat in 1890 or the 1898 crisis, through a religious lens. He saw the United States as a tool from God to punish Spain for its mistakes.

Llauder's political views were Integrist. He saw Carlism not just as a political choice but as part of God's plan. For him, the royal family was less important than the core principles. He believed Carlism was the "good tree" and Liberalism was the "bad tree." He saw Protestantism, freemasonry, and Judaism as the "gardeners" of Liberalism, leading to harmful ideas like nihilism and anarchism. He thought the government system was corrupt.

He also believed that social problems were religious problems, caused by godless Liberalism that allowed unfair profit. He described the Spanish economy as a "feudalism of money," where foreign and Jewish speculators were like lords.

While some say he was against central government and supported regional rights, others argue that regionalism was not a main theme in his writings. He saw true Traditionalists as "Spaniards of blood and heart." He viewed early Catalanism with some sympathy, thinking it was a form of unconscious Carlism. He encouraged young Catalanists, believing they would eventually join Traditionalism and its vision of a "mountainous Catalonia." However, he later realized that a key Catalanist newspaper was "systematically anti-Carlist."

See also

In Spanish: Luis María de Llauder para niños

In Spanish: Luis María de Llauder para niños

- Carlism

- Integrism (Spain)

- La Hormiga de Oro

- El Correo Catalán

- Electoral Carlism (Restoration)

- Vil·la romana de Torre Llauder

- Historia de la prensa española

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |