José María Cunill Postius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José María Cunill Postius

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Born |

José María Cunill Postius

1896 |

| Died | 1949 Terrassa, Catalonia, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | entrepreneur |

| Known for | paramilitary commander |

| Political party | Carlism |

José María Cunill Postius (1896-1949) was a Spanish Catalan businessman. He was active in a political movement called Carlism. He is best known as a leader of the Carlist youth group, the Requeté, in Catalonia. He also played a key role in plans against the Spanish Republic and the 1936 uprising in Catalonia. After the Spanish Civil War, he continued to oppose the government of Francisco Franco.

Contents

Early Life and Family

The Cunill family is very old in Catalonia, dating back to the medieval times. José María's grandfather, José Cunill Traserra, was a well-known businessman in Berga. His father, Victoriano Cunill Pujol (1860-1925), also ran a successful textile factory. By the 1920s, his father's business had many machines.

In 1883, Victoriano married Rosa Postius Sala (1864-1929). José María was born in 1896, the second of their three children. His family was very religious. José María studied at a business school in Barcelona. He became a contador mercantil, which is like an accountant. After his military service, he helped improve the family's textile business.

In 1928, José María Cunill married Mercedes Solá Brujas (1907-1993). Her family owned a lot of land near Terrassa. José María and Mercedes settled there and had eight children. One son, José María Cunill Solá, became a Catholic priest. Another son, Antonio Cunill Solá, was a deacon and worked in the Terrassa local government. His grandson, Francesc Dalmases Cunill, became a famous mountain climber.

Leading the Catalan Requeté

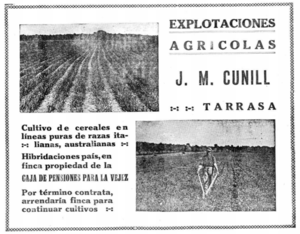

In the 1920s, Cunill managed his farming business in Terrassa. He even traded grain internationally. He faced some challenges, including fires and robberies at his warehouses. He became a leader in farming groups, becoming vice-president of the Union of Syndicates and Farmers of Catalonia in 1930.

After the Second Spanish Republic was declared in 1931, Cunill joined Peña Ibérica. This group started as a sports club but became a right-wing political group. In 1932, he ran in the Catalan parliament elections as a Traditionalist. However, his group did not win any seats.

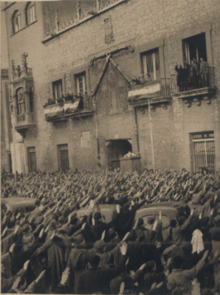

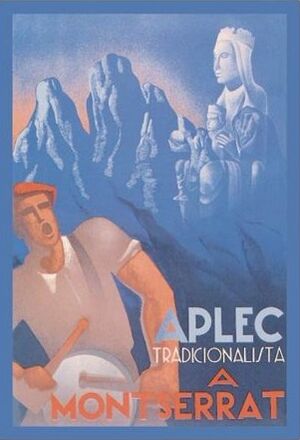

In the early 1930s, Cunill helped build the local Requeté group in Terrassa. The Requeté was a youth group linked to Carlism. Its members wore uniforms and took part in religious events. They also held training drills in the countryside. By 1933, the Terrassa group was one of the best-organized Requeté sections in Catalonia. Cunill believed in taking strong action against the Republic. He became the head of the Requeté for all of Catalonia.

Planning the Uprising

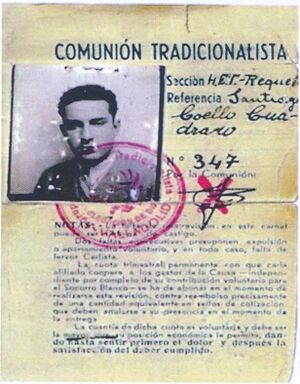

As the leader of the Catalan Requeté, Cunill worked to make the group stronger. He created a clear structure and strict rules. He also made sure members had ID cards and practiced regularly. In 1934, some Catalan Requeté members even trained in Italy. Cunill wanted the Catalan group to keep some of its own traditions, but this did not cause major problems. His work in building the Catalan Requeté was very important.

During the 1933 elections, Requeté groups guarded right-wing party offices. They even had a shootout with another group called the Escamots. In October 1934, when there was unrest, Cunill offered 500 men to help the military. He was also a member of the Terrassa local council and co-owned a local newspaper.

In 1935, Cunill represented the Requeté in España Club. This was a group in Barcelona for different extreme-right parties. They tried to form their own special units called Voluntariado Español. The Carlists seemed to be the largest and best-equipped group. After the elections in February 1936, the plan for Voluntariado was dropped.

After the Popular Front won the elections in 1936, Cunill wanted to act against the Republic. He planned for the Requeté to cause trouble, pretending to be revolutionaries. He hoped this would make the army crack down on left-wing groups. Although this plan didn't happen, Cunill stayed committed to the uprising. He kept in close contact with military leaders who were planning a coup.

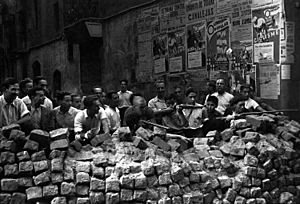

During the Civil War

Cunill was a key civilian involved in the anti-Republican plans in Catalonia in 1936. He told the military in Barcelona that he could provide about 3,000 Requeté members ready for action. On July 19, Cunill led about 200 men to the San Andrés barracks. After some fighting, the barracks were taken by government forces, and Cunill was captured. He was taken to a cemetery and shot. However, Cunill managed to pretend he was dead. He was only lightly wounded and survived. Friends helped him, and he left Barcelona. In August 1936, he reached the Nationalist side.

Cunill was one of the first Requeté members to reach the Nationalist lines after the uprising failed in Catalonia. He and Mauricio de Sivatte, another Carlist leader, worked to gather other Carlists who had escaped. They formed a special Catalan Carlist fighting group called the Tercio de Nuestra Señora de Montserrat. This group fought until the end of the war. Cunill worked behind the lines, helping with logistics and organizing Catalan Carlists.

Cunill was a strong opponent of the Unification Decree of April 1937. This decree forced all right-wing groups to join a new state party called Falange Española Tradicionalista. Cunill refused to join this new party. In January 1939, he and other Carlist leaders entered Barcelona with the Nationalist troops. They tried to reopen Carlist clubs, but the Francoist military governor ordered all clubs to close within a few days.

Opposing Franco's Government

Even though political activity was banned, Cunill helped build secret Carlist groups. He tried to use religious and official events to spread Carlist ideas. In July 1939, he was put under house arrest for two weeks for organizing an event. Police reports claimed he led a Requeté unit that wrote anti-Franco messages on walls. In 1940, security services were worried about Cunill and Sivatte, saying they caused trouble and published secret papers. They also organized a separate rally for the "Martyrs of Tradition," even though it was not allowed.

In the early 1940s, Cunill and Sivatte tried to get Traditionalists into local governments. In Terrassa, Cunill and the Marcet Cabassa brothers tried to create a group to oppose Franco's government. This group was partly hidden as a club called Peña Ibérica. Falangists, who supported Franco, accused Cunill of trying to intimidate bookstore owners into removing books by Franco. In 1943, Cunill and Francisco Vivés Suriá, carrying pistols, stormed a Falangist office to free captured Carlists. No shootout happened because there were no Carlists there.

By the mid-1940s, Cunill became frustrated with the Carlist leadership's approach to Franco's government. In 1948, he wrote to Don Javier, the Carlist claimant, complaining about the lack of strong anti-Franco actions. Don Javier asked him to trust the Carlist command but also removed him from his post as Catalan Requeté leader. Cunill continued to express his dissatisfaction. In November 1949, he signed a letter to Don Javier, urging him to declare himself king. Cunill was in the final stages of cancer at this time and passed away about two weeks later.

See also

In Spanish: José María Cunill Postius para niños

In Spanish: José María Cunill Postius para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |