Marcial Solana González-Camino facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

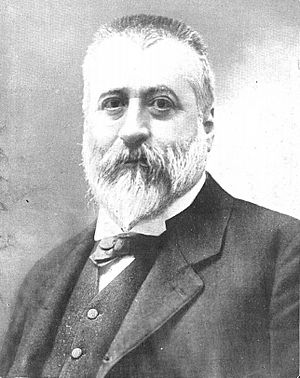

Marcial Solana González-Camino

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Born |

Marcial Solana González-Camino

1880 Santander, Spain

|

| Died | 1958 Santander, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | Landowner |

| Known for | Philosopher, political theorist |

| Political party | Carlism |

Marcial Augusto Justino Solana González-Camino (1880–1958) was an important Spanish thinker, writer, and politician. He is best known for his work on the history of philosophy, especially his huge book about Spanish thinkers from the 1500s. He also wrote about history, law, and religion. In politics, he was a key thinker for a group called Traditionalists. He was also active in many Catholic groups throughout his life.

Contents

Marcial's Early Life and Family

Marcial's family, the Solanas, were first mentioned in the 1200s. They were a noble family (called hidalguia) from a village near Santander. They often served in local government and the church.

Marcial's great-grandfather, Roque de Solana Río, was the first to live in Villaescusa. He owned many properties and became a deputy in the Spanish parliament in the 1810s. Marcial's grandfather, Pedro Solana Collado, was an army colonel. He supported the Carlists during the First Carlist War. After being exiled, he returned to Spain and built a house on the Rosequillo estate.

Marcial's father, Marcial Rufo Solana González-Camino, made the family even wealthier by trading flour in Cuba. In 1879, he married his cousin, Elvira Irene González-Camino de Velasco. Her family was also well-off from Santander.

Marcial's parents lived in Santander and had only two children: Marcial and his sister, who was born after their father passed away. They grew up in a very religious Catholic home.

In 1890, Marcial started his studies with the Jesuits in Orduña. He finished high school in 1896. He then went to the Jesuit Deusto institute, where he graduated with excellent grades in Philosophy and Literature in 1899, and in Law in 1902.

Marcial continued his studies in Madrid. He earned his PhD in Law in 1904 and another PhD in Philosophy in 1906, both with top honors.

Even though he studied law, Marcial did not become a practicing lawyer. He was a wealthy man who inherited many properties, especially in the Santander area. He lived off the money from his land. He owned several large houses, but mostly lived in Santander. In his later years, he spent summers at his favorite estate, Granja Santa María. Marcial never married or had children.

His biographer said that Marcial lived a simple life. He spent his money on books, travel, and improving his farms. However, in the 1920s, he was one of the few people in Santander who owned a car. Marcial's cousin, José Luis Zamanillo González-Camino, was also a well-known Carlist politician later on.

Joining the Integrists

Marcial's family had strong ties to Carlism, a political movement in Spain. His grandfather fought for the Carlists, and his great-uncle, Fernando Fernández de Velasco, was a Carlist politician and soldier. In the late 1880s, both joined a group called the Integrists, who were a branch of Carlism. Marcial's uncle, José Zamanillo Monreal, became the Integrist leader in Cantabria.

Since Marcial's father passed away early, his uncle and great-uncle guided him towards Integrist ideas. At first, Marcial didn't get involved in politics. Instead, he focused on Catholic activities. He joined many religious groups and helped found the Catholic Electoral Center in 1907. He also led a Catholic farmers' union.

In 1908, Marcial started speaking in public. In 1909, he became a town council member in Villaescusa. In 1910, he was elected mayor of La Concha. As mayor, he was known for fining people who offended religion or morality.

In 1910, Marcial ran for parliament as an Integrist and Catholic candidate. He said his goal was to bring "the reign of Christ" into all parts of national life. He lost the election but remained an active Integrist speaker.

He ran again in 1916 as a joint Catholic Integrist-Carlist candidate and won! During his two years in parliament, he mostly focused on budget changes that helped the Church. He didn't run in the 1918 election, but was mentioned as a possible candidate in 1919.

In the late 1910s, Marcial became a national Integrist leader. In the 1920s, he started writing important articles for El Siglo Futuro, a main Integrist newspaper. He also led local party meetings and public gatherings. In the early 1920s, he served another term as mayor of Villaescusa.

When Miguel Primo de Rivera took power in 1923 and political life slowed down, Marcial focused on his scholarly work. He continued his Catholic activities, joining the Malta Order and contributing to Catholic Action. He attended the first National Congress of Catholic Action in 1929 and spoke at many conferences.

Becoming a Carlist

Marcial always had good relationships with the Carlists. When the Second Spanish Republic was declared in 1931, he helped lead the Integrist group that wanted to join forces with the Carlists. He led a meeting in Cantabria that brought the Integrists back into the main Carlist movement, called the Comunión Tradicionalista.

At first, he didn't hold major positions in the united Carlist party. He was known for giving smart lectures about Traditionalism across Spain.

In the mid-1930s, Marcial became one of the most important Carlist thinkers. People called him a "master of Traditionalism." In 1934, the Carlist king, Alfonso Carlos, appointed him to the Council of Culture, which protected the party's core beliefs.

Marcial also advised the king on legal matters. He wrote three letters about who should become king after Alfonso Carlos. Marcial believed the king couldn't just pick his successor. Instead, an assembly of representatives had to be involved. This advice likely helped lead to the solution that was eventually chosen.

Marcial was a strong supporter of monarchist groups working together. He also wrote about the "right to resist" a bad government. This idea was seen by some as a hint about the military uprising in 1936.

It's not clear if Marcial knew about the Carlist plans for the coup. However, he knew he might be a target if violence broke out, so he had two secret hiding places on his properties. In August 1936, he went to France but soon returned. He spent 1937 in Valle de Baztan. After the Nationalists took control of Cantabria, he returned to his Rosequillo estate.

Marcial was not an active member of the Carlist leadership, but he sided with Manuel Fal Conde against the Unification Decree in 1937, which merged different political groups. Some historians think he helped write a letter to Francisco Franco in 1939, asking for the Traditionalist monarchy to be restored. In the early 1940s, he was fined for being involved in Carlist activities that were technically illegal.

Marcial wasn't very active in daily party work in the 1940s. However, some scholars say his ideas were crucial for keeping the Carlist identity strong against Franco's government. He might have attended some important meetings, including a gathering of regional leaders in 1947.

In 1951, he managed to publish El tradicionalismo político español y la ciencia hispana. He had finished this study in 1938. Today, it is seen as one of the most important works on Traditionalism and his biggest contribution to Carlism. After this, Marcial became less involved in politics and focused on his scholarly and Catholic duties.

A Spanish Philosopher

Marcial spent most of his academic time studying philosophy. He was especially good as a historian of philosophy. He wanted to know if there was a unique "Spanish philosophy" with special features. His answer was yes!

He believed that a truly Spanish way of thinking developed in the 1500s, known as the Golden Age. This philosophy was shaped by thinkers like Juan Luis Vives, Francisco de Vitoria, Francisco Suárez, Domingo de Soto, and Domingo Báñez. It included many ideas, but its main part was a later form of Scholasticism, a type of philosophy that combines faith and reason. This led to new ideas in areas like logic, natural law, and international law.

Marcial saw the Golden Age as a time when traditional ideas faced new ones. He believed the heart of Spanish philosophy was its connection to religion, its loyalty to Catholic values, and its way of looking at things as a whole. He preferred metaphysics (the study of reality) and epistemology (the study of knowledge). He often quoted Aquinas and Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo. He showed little interest in Liberal thinkers or foreign philosophers.

Marcial wrote about 60 works on philosophy and theology, though most were short pieces. His most important work in philosophy is La Historia de la Filosofía Española. Época del Renacimiento. This huge three-volume book was written between 1928 and 1933 and published in 1941. A smaller book that summarized his ideas was Fueron los españoles quienes elevaron la filosofía Escolástica a la perfección (1955).

He also wrote a large book on legal systems based on Thomism, a philosophy following the ideas of Thomas Aquinas (1925). He wrote many smaller works on Scholastic thinkers and Traditionalists. Marcial also published about 30 shorter works on theology, covering topics like the Trinity and the Eucharist.

His only major work not about the history of philosophy or theology was an unpublished study called La libertad del hombre (1947). In this book, he discussed human freedom within Catholic teachings. He disagreed with the Liberal idea of freedom and believed that choosing between good and evil was not true freedom.

Ideas on Politics

Marcial's political ideas followed the typical Traditionalist pattern. He believed the main goal of politics was "God's social rule." He thought a good government should have three principles:

- A "hereditary monarchy," meaning a king or queen whose power is passed down through family.

- A "tempered monarchy," where the king's power is balanced by groups representing society.

- "Decentralization and self-sufficiency," meaning local communities should have a lot of self-government.

Marcial's special contribution was updating Traditionalist ideas to deal with new totalitarian theories (like those in Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia) that appeared in the 1920s and 1930s.

Marcial's ideas strongly opposed tyranny. He believed in a monarchy where the king's power was limited. He also largely ignored the ideas of Víctor Pradera Larumbe, another Carlist thinker who supported dictatorial solutions. During the Second Spanish Republic, Marcial wrote about the right to resist and overthrow a tyrannical government.

A new idea Marcial brought to Traditionalism was showing that it could not mix with totalitarian ideas. He strongly criticized Soviet, Fascist, and Nazi governments. He said their tyranny, worship of the state, and extreme nationalism made them "irreconcilable Traditionalist enemies."

His main theoretical work, finished in 1938, included a hidden warning to Franco. It said that Traditionalists would never support a government based on foreign ideas. It also expressed sadness about the "terrible civil war that bleeds the Homeland" and feared that "so much blood and so many ruins and so many misfortunes" might be for nothing.

Like some Traditionalists, Marcial welcomed democracy, but he saw it simply as a way for people to be represented. He also spoke about "human rights" and praised religious and educational freedoms, as long as they were "rightly understood" and "for lawful purposes." He noted that society exists for people, not the other way around.

Some of his writings had very strong passages about the special role of Spaniards, which sounded a bit like typical nationalist talk, unusual for Traditionalism. Finally, even though his movement was proud of its fighting past, Marcial was unusually bold in condemning "the spirit of violence." He mostly applied this to foreign ideas, but he also noted that the famous "Traditionalist strictness" had its limits. He considered himself a Traditionalist first, rather than just a Carlist.

As a political thinker, Marcial didn't write a huge amount. His main work is El Tradicionalismo político español y la ciencia hispana, written in 1937-1938 and published in 1951. It explains his vision of a Traditionalist government within the Spanish historical context. Another important work is La resistencia a la tiranía (1933), about resisting tyranny. He also wrote about 10 smaller pieces, including unpublished letters to Alfonso Carlos that were actually legal discussions about Carlist succession rules.

Other Works and Activities

Marcial published about 40 works on history, mostly short newspaper articles from the 1910s to the 1950s. None of them were of major general importance. His most notable history works were two medium-sized biographies and two studies on family crests (heraldry). Besides his PhD thesis in law, he didn't write much else about legal science. He also wrote several works about Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, a scholar Marcial greatly admired.

Besides writing, Marcial helped Spanish culture and science as a leader and activist. In the 1920s, he joined the Menéndez Pelayo Society and contributed to its newsletter. In 1940, he became a member of its board. In 1934, he helped start the Center for Montañes Studies, becoming a board member and head of the biography section. He became vice-president in 1939 and president in 1940.

Since the 1930s, he participated in the Spanish Association for the Progress of Sciences. In 1940, Marcial joined the Spanish National Research Council. In 1945, he was invited to join the Royal Academy of Moral and Political Sciences as a corresponding member, which he officially joined in 1951. In 1951, he was named the official historian of the Royal Valley of Villaescusa. In the 1950s, he became a member of many local Santander groups, including the Patronage of Prehistoric Caves and the Provincial Council of Culture. Although he wasn't very active outside his home region of Cantabria, he sometimes gave lectures on 16th-century Spanish philosophy to academic groups elsewhere.

Marcial was also constantly active in religious organizations. During his university years, he was involved in many Catholic groups. In the 1920s, he joined the Malta Order and contributed to various religious gatherings. He was very active in Catholic Action. In the 1930s, he was even considered for membership in the Pontifical Academy of Sciences.

In the 1940s, he mostly worked with the local church leaders in Santander, for example, joining a committee for reconstruction projects. In the 1950s, he acted as a lawyer for some properties owned by the Santander diocese. He also gave money to help renovate local churches.

See also

In Spanish: Marcial Solana González-Camino para niños

In Spanish: Marcial Solana González-Camino para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |