Cornelio Saavedra facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

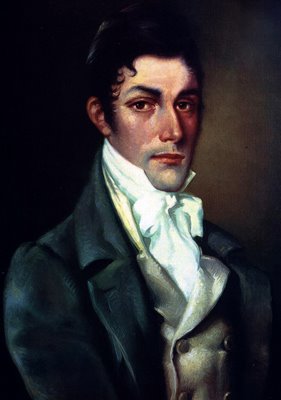

Cornelio Saavedra

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 1st President of the Primera Junta and the Junta Grande in the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata | |

| In office May 25, 1810 – August 26, 1811 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Domingo Matheu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 15, 1759 Otuyo, Viceroyalty of Peru (present-day Bolivia) |

| Died | March 29, 1829 Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Resting place | La Recoleta Cemetery |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Political party | Patriot |

| Spouse | Saturnina Saavedra |

| Children | Mariano Saavedra |

| Profession | Military |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, United Provinces of the Río de la Plata |

| Years of service | 1806–1811 |

| Commands | Regiment of Patricians |

| Battles/wars | British invasions of the Río de la Plata, Mutiny of Álzaga |

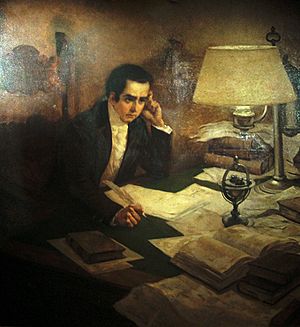

Cornelio Judas Tadeo de Saavedra y Rodríguez (born September 15, 1759, in Otuyo – died March 29, 1829, in Buenos Aires) was an important military leader and politician. He lived in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, which was a Spanish colony in South America. He played a key role in the May Revolution, which was the first big step towards Argentina becoming independent from Spain. After the revolution, he became the first president of the Primera Junta, the new government.

Saavedra led the Regiment of Patricians, a special army group formed after the British tried to invade Buenos Aires. Because the city became more military-focused, and old social rules changed, people born in America (called criollos) like Saavedra became very important. He helped stop a rebellion led by Martín de Álzaga, which allowed the Spanish ruler, viceroy Santiago de Liniers, to stay in power. Saavedra wanted a new government run by criollos, but he was careful and waited for the right moment. That moment came in May 1810, when the May Revolution successfully removed the viceroy.

As president of the Primera Junta, Saavedra soon disagreed with the secretary, Mariano Moreno. Saavedra wanted slow changes, while Moreno pushed for faster, more radical ones. Saavedra supported bringing in leaders from other provinces to join the government, which made Moreno a minority. Moreno resigned, and later, a rebellion supporting Saavedra forced Moreno's remaining friends to also resign. Saavedra left the presidency after a military defeat and went to lead the army. His political rivals used his absence to create a new government, the First Triumvirate, and even ordered his arrest. Saavedra lived away from Buenos Aires until 1818, when all charges against him were dropped.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Family

Cornelio Saavedra was born on September 15, 1759, on a farm called "La Fombera." This farm was near the city of Potosí, in what is now Bolivia. At that time, Potosí was part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, a large Spanish colony. Later, it became part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata.

His father, Santiago Felipe de Saavedra y Palma, was from Buenos Aires. His mother, María Teresa Rodríguez Michel, was from Potosí. They were a wealthy family with many children, and Cornelio was the youngest. In 1767, his family moved to Buenos Aires.

As a teenager, Cornelio went to the Real Colegio de San Carlos. This was a special school for the children of important families. He studied philosophy and Latin from 1773 to 1776. However, he couldn't finish school because he had to help manage his family's ranch. Unlike many other rich young men, he did not go to university.

In 1788, he married his cousin, Maria Francisca Cabrera y Saavedra, who was also wealthy. They had three sons: Diego, Mariano, and Manuel. Francisca died in 1798.

Saavedra started his political career in 1797. He worked for the Buenos Aires Cabildo, which was the city's local government. Buenos Aires was now the capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. He held different administrative jobs, like being an alderman. In 1801, he became the Mayor of First Vote. That same year, he married his second wife, Doña Saturnina Otárola del Rivero.

Leading the Patricians Regiment

Fighting the British Invasions

In 1806, British forces attacked Buenos Aires in what are known as the British invasions of the Río de la Plata. Cornelio Saavedra was a civilian at the time. Santiago de Liniers gathered an army in Montevideo to take Buenos Aires back. Saavedra joined Liniers, even though he had no military training. Liniers successfully recaptured the city.

After this, Liniers prepared Buenos Aires for another British attack. All men aged 16 to 50 had to join the army. They were divided into groups based on where they came from. The biggest group was the Regiment of Patricians. This group was made up of volunteer soldiers born in Buenos Aires. The soldiers in this regiment could choose their own leaders, and they chose Cornelio Saavedra to lead them.

The British returned in 1807. Saavedra marched towards Montevideo, but he learned that the city had already been captured. The British planned to use Montevideo to attack Buenos Aires. To stop them, Saavedra ordered all military supplies to be moved from Colonia (which couldn't be defended) to Buenos Aires. This helped strengthen the city's defenses.

The British attacked Buenos Aires again on July 5. This time, they had 8,000 soldiers and 18 cannons, much more than before. After a small victory outside the city, the British army entered Buenos Aires. However, they faced strong resistance from everyone, including women, children, and even slaves.

Saavedra and Juan José Viamonte led the Regiment of Patricians from their headquarters at the Real Colegio de San Carlos. They fought off a British group. Other British groups were also defeated by the local soldiers. Finally, the British General John Whitelocke surrendered. He promised to remove all British forces from Montevideo.

Saavedra's Growing Influence

The victory against the British changed politics in Buenos Aires. The viceroy, Sobremonte, was seen as a bad leader, and the Cabildo (city council) became more powerful. The Cabildo even removed the viceroy and appointed Liniers in his place, which was a huge and unusual step.

Local people born in America, the criollos, had limited chances to gain power under the old system. But with the rise of the militias, they got their chance. Cornelio Saavedra, as the leader of the largest criollo militia, became a very influential person in Buenos Aires politics. He felt that Spain wasn't doing enough to support the war effort, especially compared to the help received from other cities in America. Because of this, he was loyal to the new viceroy, Liniers, who was French.

Stopping the Álzaga Mutiny

Political Crisis in Spain

The Peninsular War in Spain caused a big crisis in the Spanish colonies. The Spanish king, Ferdinand VII, was captured by Napoleon. This led to different ideas about how to govern the colonies. Some criollos, like Manuel Belgrano and Juan José Castelli, supported a plan called Carlotism. This plan wanted to crown Carlota Joaquina, a Spanish princess, as queen. It's not clear if Saavedra supported this idea. Carlotism didn't last long, and people started looking for other solutions.

In Montevideo, Francisco Javier de Elío created a new government group called a Junta, similar to those in Spain. His friend in Buenos Aires, Martín de Álzaga, wanted to do the same.

Saavedra's Decisive Action

On January 1, 1809, the Mutiny of Álzaga began. Álzaga accused Viceroy Liniers of trying to appoint loyal members to the Cabildo. He gathered a small protest to demand Liniers' resignation. The rebels, supported by some Spanish militias, took over the main square. Liniers was about to resign to avoid more conflict.

Cornelio Saavedra knew about this plan. He saw it as an attempt by people from Spain (called peninsulars) to take power from the criollos. He quickly marched the Regiment of Patricians to the square and stopped the mutiny. There was no fighting, as the criollos' large numbers simply forced the rebels to give up. Because of Saavedra, Liniers remained viceroy. The leaders of the mutiny were sent to prison, and the militias that joined them were disbanded. This meant that criollos gained military control, and Saavedra's political power grew even more.

A few months later, a new viceroy, Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros, was appointed. Some patriots wanted to keep Liniers in power and resist the new viceroy. However, Saavedra and Liniers themselves didn't agree, so the change happened peacefully. Saavedra supported the criollos' plans to take power, but he warned against rushing. He believed the best time to act would be when Napoleon's forces had a clear advantage in Spain. Until then, he kept other revolutionaries quiet by refusing to let his regiment help. He often said, "Peasants and gentlemen, it is not yet time – let the figs ripen, and then we'll eat them."

The May Revolution

The Right Moment Arrives

The chance Saavedra had been waiting for came in May 1810. Two British ships brought news that the Spanish city of Seville had been invaded. The Junta of Seville, which governed Spain, had stopped working. Some members had fled to Cadiz and Leon, the last parts of Spain not taken by Napoleon. It looked like Spain was about to be completely defeated.

Viceroy Cisneros tried to hide this news by taking all newspapers. But some papers reached the revolutionaries. Colonel Viamonte called Saavedra and told him the news, asking for his military support again. Saavedra agreed that it was the perfect time. He famously said, "Gentlemen: now I say it is not only time, but we must not waste a single hour."

Cisneros then asked Saavedra and Martín Rodríguez for their military support in case of a rebellion. They refused. Saavedra argued that Cisneros should resign because the Junta that appointed him no longer existed. Cisneros then agreed to Juan José Castelli's request for an open cabildo. This was a special meeting of important people in the city to discuss the situation.

The next day, an armed crowd, led by Antonio Beruti and Domingo French, gathered in the main square. They demanded the open cabildo, worried that Cisneros might not allow it. Saavedra spoke to the crowd and assured them that the Regiment of Patricians supported their demands.

Forming a New Government

The open cabildo was held on May 22. People discussed whether Cisneros should stay in power and, if he was removed, what kind of government should be formed. Saavedra mostly listened, waiting for his turn to speak. Many important people spoke. Saavedra was the last to speak. He suggested that the Cabildo should temporarily take control until a new governing Junta could be formed. He said, "And there be no doubt that it is the people that confers the authority or command." This idea, called Retroversion of the sovereignty to the people, meant that if the rightful ruler was gone, power returned to the people, who could then choose new leaders. Castelli agreed with Saavedra, and their idea won with 87 votes.

However, the Cabildo then appointed a Junta that still included Cisneros as its head, though in a new role. Saavedra and Castelli were also appointed to this Junta. They took an oath, but the people were very unhappy. They felt this went against what was decided at the open cabildo. That night, Saavedra and Castelli resigned, and convinced Cisneros to do the same.

The Cabildo didn't want to accept Cisneros' resignation. They ordered the military to control the crowd. But the military commanders said their soldiers would rebel if they did. As the protest grew, Cisneros' resignation was finally accepted. The members of the new Junta were chosen from a document with hundreds of signatures, gathered from the people in the square. Cornelio Saavedra became the president of this new Junta. He first refused, worried people would think he started the revolution for himself. But Cisneros asked him to accept, and he did.

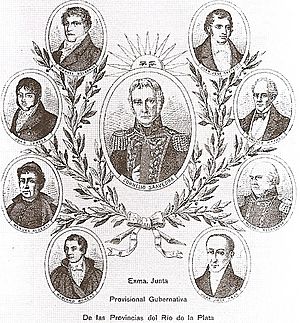

The Junta was officially formed on May 25. Other cities were invited to send representatives to a meeting to discuss the new government. They were also invited to send representatives to join the Junta itself. These two invitations were a bit confusing, and this would cause problems later.

It's not completely clear who wrote the document that named the Junta members. Saavedra later wrote in his memoirs that it was "the people." Since he protested being named president, he probably wasn't part of the discussions about who would be in the Junta. The Regiment of Patricians probably didn't choose the members either, because the Junta wasn't a military government (only two of nine members were military), and they wouldn't have chosen Moreno, who was known to be Saavedra's rival. A common idea is that the Junta was a balance between different political groups.

Saavedra's high influence as a military leader made him president of the Junta. From then on, he spent most of his time at the fort in Buenos Aires, leading the government with Moreno, Belgrano, and Castelli. He likely put his own businesses aside for this important work.

The Primera Junta

Facing Royalist Threats

Cornelio Saavedra knew that the new government, the Primera Junta, would face resistance from those still loyal to Spain. The local Cabildo and the Royal Audiencia (a high court) resisted it. Nearby cities like Montevideo and Paraguay also didn't recognize the Junta. And Santiago de Liniers organized a counter-revolution in Córdoba.

In these early days, the Junta worked together against these threats. Mariano Moreno, the secretary of war, wrote the rules to deal with royalists. First, a rule was made to punish anyone causing trouble or hiding plots against the Junta. The Royal Audiencia swore loyalty to the Spanish Regency Council, defying the Junta. So, they and former viceroy Cisneros were sent away to Spain. The Junta then appointed new members to the Audiencia who supported the revolution.

Moreno also organized military campaigns to Paraguay and Upper Peru (modern-day Bolivia), where cities resisted the Junta. The army sent to Córdoba was ordered to capture the counter-revolutionary leaders. When the counter-revolution grew stronger, Moreno suggested to the Junta that the enemy leaders should be shot immediately after capture, instead of being brought to trial. Juan José Castelli carried out these new orders. Cornelio Saavedra supported all these actions.

Saavedra and Moreno's Differences

As time went on, Saavedra and Moreno grew apart. At first, there was some distrust of Saavedra in the Junta, but this was mostly because he liked honors and special treatment, not because of a power struggle. Once the first problems were solved, Saavedra wanted a more forgiving approach, while Moreno pushed for radical actions.

For example, the Junta found out that some Cabildo members secretly swore loyalty to the Spanish Regency Council. Moreno wanted to execute them to scare others. Saavedra argued that the government should be lenient and refused to use his Regiment of Patricians for such executions. Saavedra's view won, and the plotting Cabildo members were exiled instead of executed. Moreno was supported by some military groups and activists. Saavedra was supported by merchants, those loyal to the old system who saw him as a lesser evil, and his large Regiment of Patricians.

To reduce Saavedra's power, Moreno tried to change military promotion rules. Before, sons of officers were automatically cadets and promoted by how long they served. Moreno wanted promotions to be based on military achievements. However, this change upset many military members who had benefited from the old rules.

Saavedra believed that the victory at the battle of Suipacha meant the Junta had defeated its enemies. He thought Moreno's dislike of him came from the Álzaga mutiny, which Moreno had been part of. After the victory, officers in the Patricians' barracks toasted Saavedra as if he were a king. When Moreno heard this, he wrote the Honours Suppression decree, which removed the special ceremonies and privileges of the Junta's president. Saavedra signed it without complaint. The Patricians resented Moreno for this, but Saavedra thought it was an overreaction to a small issue.

The Junta Grande Forms

The arrival of representatives from other provinces, who had been invited months ago, caused new arguments. Mariano Moreno believed these representatives should form a separate assembly to write a constitution. He wrote this in the Gazeta de Buenos Ayres newspaper. However, most of the representatives supported Saavedra's more moderate style. Led by Gregorio Funes from Córdoba, they wanted to join the existing Junta, as the second invitation had suggested. Saavedra and Funes thought this would make Moreno a minority, unable to push his radical ideas.

On December 18, the representatives and the Junta met to decide. Funes, who was close to Saavedra, argued that Buenos Aires alone couldn't appoint national leaders and expect other provinces to obey. The nine new representatives voted to join the Junta, as did some of the original Junta members. Saavedra said that joining wasn't fully legal, but he supported it for the good of the public. Only Juan José Paso voted with Moreno against the new members joining. Being in the minority, Moreno resigned. He was sent on a diplomatic mission to Europe but died at sea under unclear circumstances.

The Junta Grande and Its Challenges

With the new members, the Junta was renamed the Junta Grande. Cornelio Saavedra remained president and had clear control, along with Gregorio Funes. Even though Moreno was gone, his former supporters still plotted against Saavedra. They accused Funes and Saavedra of supporting Carlotism. A military group tried to rebel, but they were discovered and defeated.

The conflict was finally settled by the Revolution of the shoreline dwellers. Supporters of Saavedra led poor people from the outskirts of Buenos Aires, along with the Regiment of Patricians, to the main square. They demanded that Moreno's supporters resign from the Junta. New members who supported Saavedra were appointed. They also demanded that the government's political style shouldn't change without a vote. However, Saavedra later said in his autobiography that he had no part in this revolution and condemned it.

From this point, Saavedra began to lose political power. Moreno's decree changing military promotions, which was never canceled, started to have an effect. The army became more professional and less based on militias. Many new military leaders opposed Saavedra. The political crisis worsened because the war was going badly: Belgrano was defeated in Paraguay, Castelli in Upper Peru, and capturing Montevideo became very difficult. The many members of the Junta made it hard to make quick decisions needed for the war. Saavedra left Buenos Aires and went to Upper Peru to take command of the Army of the North. He believed he could help more as a military leader than by dealing with the political struggles in Buenos Aires.

Fall and Exile

Saavedra was warned by other Junta members, military leaders, and even the Cabildo that if he left Buenos Aires, the government would face a political crisis. But he left anyway, convinced he could reorganize the Army of the North. The warnings were right. Soon after he left, the Junta's power was reduced to a legislative role, and the executive power was given to the First Triumvirate. This new arrangement didn't last long, and the Junta was eventually abolished. The Regiment of Patricians tried to rebel against the Triumvirate but failed.

Saavedra received the news eight days after arriving in Salta. He was told he was no longer president and had to give command of the Army of the North to Juan Martín de Pueyrredón. To avoid returning to Buenos Aires, he asked to be moved to Tucumán or Mendoza. He was allowed to stay in Mendoza, where he rejoined his wife and children. The newspapers in Buenos Aires were very critical of him. The Triumvirate then asked the governor to arrest Saavedra and send him to Luján, near Buenos Aires. However, this order was never carried out because the Triumvirate was overthrown by the Revolution of October 8, 1812, and a new government, the Second Triumvirate, took its place.

The new leader, Gervasio Antonio de Posadas, was hostile towards Saavedra. Posadas had been exiled in 1811, and he sought revenge by putting Saavedra on trial. Saavedra was accused of organizing the 1811 revolution. The court ruled that Saavedra should be exiled. He avoided this by crossing the Andes mountains with his son and seeking safety in Chile. Juan José Paso asked Chile to send Saavedra back, but the Chilean leader refused. Saavedra didn't stay long in Chile. A large royalist attack on Chile, which led to the Disaster of Rancagua and Chile being retaken by royalists, forced him to cross the Andes again. He found refuge in Mendoza, along with other Chileans. José de San Martín, who was governing Mendoza at the time, allowed him to settle in San Juan.

Saavedra lived in San Juan from 1814. He had another son, Pedro Cornelio, and lived a simple life growing grapes. He waited for Posadas' final decision. But Posadas faced his own political problems. The Spanish king had returned and demanded the colonies go back to being Spanish. Royalists in Upper Peru were still a threat, and José Gervasio Artigas opposed Buenos Aires because of its strong central control. As a result, Carlos María de Alvear became the new supreme director, and he would decide Saavedra's fate.

Last Years and Legacy

Alvear ordered Saavedra to come to Buenos Aires to close his case. Saavedra arrived in time, and Alvear was sympathetic to him. However, Alvear was forced to resign a few days later, before he could make a ruling. The Buenos Aires Cabildo, which was the temporary government, gave Saavedra back his military rank and honors. But the next supreme director, Ignacio Álvarez Thomas, canceled this. Saavedra then moved to the countryside to live with his brother. He kept asking the government to restore his rank.

Finally, the supreme director Juan Martín de Pueyrredón appointed a group to discuss Saavedra's case. By this time, the Congress of Tucumán had declared Argentina's independence a couple of years earlier. The group restored Saavedra's military rank as brigadier. They also ordered that he be paid all the wages he missed while he was demoted. A second group confirmed this decision. The payment wasn't enough to cover all Saavedra's losses, but he saw it as a sign that his good name was restored. He was then asked to help protect the border with native groups in Luján.

Saavedra was upset that Buenos Aires did nothing during the Luso-Brazilian invasion of the Banda Oriental (modern-day Uruguay). So, Francisco Ramírez from Entre Ríos and Estanislao López from Santa Fe joined forces against Buenos Aires. Saavedra fled to Montevideo, fearing Buenos Aires would be destroyed if defeated. Ramírez and López won the Battle of Cepeda, but the city was not destroyed, so Saavedra returned. He retired in 1822 and lived with his family in the countryside. He offered to serve in the War of Brazil, even though he was 65, but his offer was declined. He wrote his memoirs, Memoria autógrafa, in 1828.

Cornelio Saavedra died on March 29, 1829. His sons took him to the cemetery. There was no state funeral at the time because Juan Lavalle had overthrown the governor Manuel Dorrego and executed him, starting a period of civil war. Lavalle was later defeated by Juan Manuel de Rosas, who became governor. Once peace was restored, Rosas held a state funeral for Saavedra on January 13, 1830.

Legacy

As the president of the first government body created after the May Revolution, Saavedra is seen as the first ruler of Argentina. However, the Spanish Juntas were not like a modern presidential system. So, Saavedra was not the first President of Argentina; that office was created much later. The Casa Rosada, which is the official home of the President of Argentina, has a bust of Saavedra in its "Hall of Busts."

The Regiment of Patricians is still an active part of the Argentine Army today. It is now an air assault infantry unit. It also guards the Buenos Aires Cabildo and serves as an honor guard for visiting foreign leaders and the City Government of Buenos Aires. In 2010, the regiment's headquarters building was declared a National Historical Monument.

The way historians view Cornelio Saavedra is often linked to how they view Mariano Moreno. Because Saavedra had conflicts with Moreno in the Junta, opinions about him often reflect opinions about Moreno. Early historians who supported liberal ideas praised Moreno as the revolution's leader. Saavedra was sometimes seen as weak or even against the revolution. This view didn't fully recognize that Saavedra, as head of the Patricians, was very popular and influential in the city even before the revolution.

Later, other historians criticized Moreno, sometimes calling him a British agent or someone with ideas that didn't fit South America. They saw Saavedra as a popular leader, a bit like José de San Martín or Juan Manuel de Rosas. However, this view didn't fully recognize that wealthy citizens supported Saavedra against Moreno, that Saavedra himself was wealthy, and that the 1811 revolution didn't ask for social changes, only for Moreno's supporters to be removed from the Junta.

Descendants

Some of Cornelio Saavedra's notable descendants include:

- His son Mariano Saavedra, who was governor of the Province of Buenos Aires twice between 1862 and 1865.

- His grandson Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez, a Chilean military officer who led the Occupation of Araucania.

- His great-grandson Carlos Saavedra Lamas, a politician and diplomat who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1936.

The Saavedra neighborhood in Buenos Aires was named after his nephew, Luis María Saavedra, who was a successful businessman in the late 1800s.

A descendant of his brother, Luis Gonzaga Saavedra, was León Ibáñez Saavedra. León's daughter, Matilde Ibáñez Tálice, became the First Lady of Uruguay (1947–1951) and was the mother of Uruguayan President Jorge Batlle Ibáñez (2000–2005).

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |