Quechuan languages facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Quechuan |

|

|---|---|

| Kechua / Runa Simi | |

| Ethnicity: | Quechua |

| Geographic distribution: |

Throughout the central Andes Mountains including Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. |

| Linguistic classification: | One of the world's primary language families |

| Subdivisions: |

Quechua I

|

| ISO 639-5: | qwe |

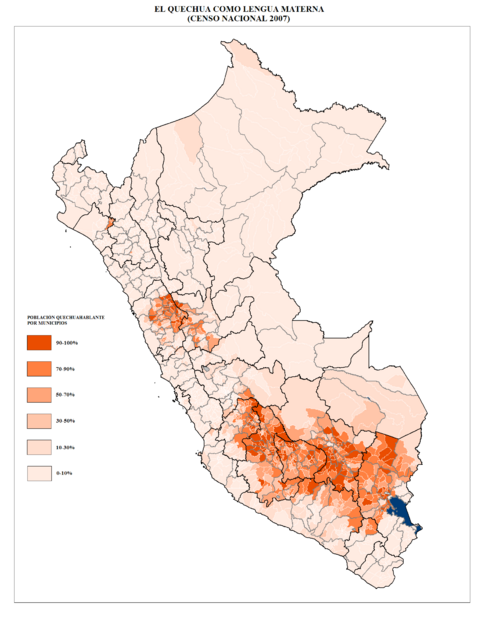

Map showing the distribution of Quechuan languages

|

|

| Person | Runa / Nuna |

|---|---|

| People | Runakuna / Nunakuna |

| Language | Runasimi / Nunasimi |

Quechua is a group of languages spoken by the Quechua people. Most of these people live in the Andes Mountains of Peru. In the Quechuan languages, it is often called Runasimi, which means "people's language."

Quechua is the most widely spoken group of languages from before the time of Christopher Columbus in the Americas. About 8 to 10 million people spoke it in 2004. In Peru, about 25% of people (7.7 million) speak a Quechuan language.

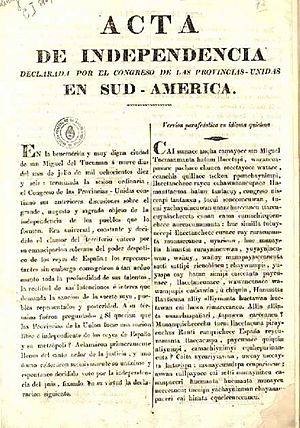

Quechua was the main language family of the Inca Empire. The Spanish rulers encouraged people to use it. But this changed during the Peruvian fight for freedom in the 1780s. Even so, different types of Quechua are still widely spoken today. It is an official language in many areas and the second most spoken language family in Peru.

Contents

History of Quechua

Quechua languages were already spread across the central Andes long before the Inca Empire grew. The Inca people were just one of many groups in Peru who already spoke a form of Quechua. In the Cusco area, Quechua changed because of languages like Aymara. This caused it to develop differently there.

In the same way, different dialects (local versions) grew in other areas. This happened as the Inca Empire ruled and made Quechua its official language.

After the Spanish conquest of Peru in the 1500s, Quechua continued to be used a lot by the native people. The Spanish government even recognized it. Many Spaniards learned Quechua to talk with the local people. Priests from the Catholic Church also used Quechua to spread their religion.

The first written records of Quechua were made by a missionary named Domingo de Santo Tomás. He came to Peru in 1538 and learned the language. In 1560, he published a grammar book about it. Because Catholic missionaries used it, Quechua continued to spread in some areas.

In the late 1700s, Spanish officials stopped using Quechua for government and religious purposes. They banned it from public use in Peru after the Túpac Amaru II rebellion by native peoples. The Spanish Crown even banned books written in Quechua.

After countries in Latin America became independent in the 1800s, Quechua had a short comeback. But its importance quickly went down. Slowly, fewer people spoke it, mostly in isolated rural areas. However, in the 2000s, 8 to 10 million people across South America speak Quechua. This makes it the most spoken native language there.

Because the Incas expanded into Central Chile, some Mapuche people there spoke both Quechua and Mapudungu. It is thought that these three languages – Mapuche, Quechua, and Spanish – were all used in Central Chile in the 1600s. Quechua has influenced Chilean Spanish more than any other native language.

Place names that mix Quechua, Aymara, and Mapudungu can be found far south in Chile.

In 2017, the first university thesis written in Quechua in Europe was defended. It was by Peruvian Carmen Escalante Gutiérrez in Spain. That same year, Pablo Landeo wrote the first novel in Quechua without a Spanish translation. In 2019, a Peruvian student, Roxana Quispe Collantes, defended the first thesis in Quechua at her university.

Today, many groups are working to promote Quechua. Many universities teach Quechua classes. Organizations like Elva Ambía's Quechua Collective of New York help spread the language. Governments are also training interpreters in Quechua for healthcare, legal, and other services.

Quechua Today

In 1975, Peru was the first country to make Quechua one of its official languages. Ecuador made it official in its 2006 constitution. In 2009, Bolivia also recognized Quechua and other native languages as official.

A big challenge for using and teaching Quechuan languages is the lack of written materials. There are not many books, newspapers, or magazines in Quechua. The Bible has been translated into Quechua by some missionary groups. Quechua, along with Aymara and other smaller native languages, is mostly a spoken language.

Recently, Quechua has been taught in special bilingual schools in Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador. But even in these areas, governments only reach some of the Quechua-speaking people. Some native people in these countries prefer their children to study in Spanish to help them get ahead in society.

Radio Nacional del Perú broadcasts news and farming programs in Quechua in the mornings.

Quechua and Spanish are now very mixed in the Andes region. Many Spanish words are used in Quechua. Also, Spanish speakers often use Quechua phrases and words. For example, in southern Bolivia, words like wawa (baby), misi (cat), and waska (strap) are common. Quechua has also greatly influenced other native languages, like Mapuche.

How Many People Speak Quechua?

The number of Quechua speakers changes a lot depending on who you ask. In 2002, one source said there were 10 million speakers. But this number was based on older figures. For example, the number for Imbabura Highland Quechua was from 1977.

Another group estimated one million Imbabura dialect speakers in 2006. Census numbers can also be tricky because not all speakers are counted. The 2001 Ecuador census reported only 500,000 Quechua speakers. But most language experts estimate more than 2 million. The censuses of Peru (2007) and Bolivia (2001) are thought to be more accurate.

Here are some speaker numbers:

- Argentina: 900,000 (1971)

- Bolivia: 2,100,000 (2001 census); 2,800,000 South Bolivian (1987)

- Chile: Very few; 8,200 in the ethnic group (2002 census)

- Colombia: 4,402 to 16,000

- Ecuador: 2,300,000 (1991)

- Peru: 3,800,000 (2017 census); 3,500,000 to 4,400,000 (2000)

There are also many Quechua speakers who have moved to other countries. Their numbers are not known.

Types of Quechua

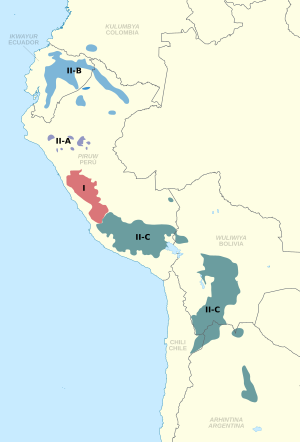

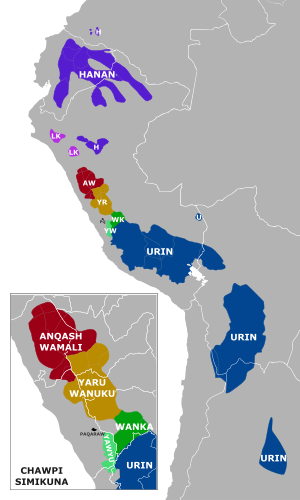

There are big differences between the Quechua spoken in the central Peruvian highlands and the versions spoken in Ecuador, southern Peru, and Bolivia. These are often called Quechua I (or Central Quechua) and Quechua II (or Peripheral Quechua). Within these two main groups, the languages blend into each other. This means speakers from nearby areas can usually understand each other.

However, there is a second division in Quechua II. This is between the simpler northern versions in Ecuador, called Quechua II-B or Kichwa, and the more traditional versions in the southern highlands, called Quechua II-C. The Quechua II-C group includes the language spoken in Cusco, the old Inca capital. The languages are similar partly because Cusco Quechua influenced the Ecuadorian versions during the Inca Empire. Inca nobles had to send their children to Cusco for education. This made Cusco Quechua a very important and respected dialect in the north.

Speakers from different parts of the three main regions can usually understand each other fairly well. But there are still important local differences. For example, Wanka Quechua is quite different and harder for other Central Quechua speakers to understand. Speakers from very different main regions, like Central or Southern Quechua, usually cannot understand each other well.

Because the different dialects are not easily understood by each other, Quechua is seen as a language family, not just one language. It is hard to separate them into clear groups because they change gradually. One source lists 45 varieties, divided into Central and Peripheral groups. Since these two groups are not mutually understandable, they are seen as separate languages.

The overall differences within the Quechua family are less than in the Romance (like Spanish, French) or Germanic (like English, German) language families. They are more like the differences in Slavic (like Russian, Polish) or Arabic. The biggest differences are found in Central Quechua (Quechua I). This area is believed to be where the original Proto-Quechua language started.

Where Quechua is Spoken

Quechua I (Central Quechua) is spoken in the central highlands of Peru. This stretches from the Ancash Region to Huancayo. It is the most diverse branch of Quechua. Its different parts are often seen as separate languages.

Quechua II (Peripheral Quechua) has three main parts:

- II-A: Yunkay Quechua is found in scattered areas of Peru's western highlands.

- II-B: Northern Quechua (also called Runashimi or Kichwa) is mainly spoken in Colombia and Ecuador. It is also found in the Amazon lowlands of these countries and in small areas of Peru.

- II-C: Southern Quechua is spoken in the southern highlands. This includes the Huancavelica, Ayacucho, Cusco, and Puno regions of Peru. It is also spoken across much of Bolivia and in parts of northwestern Argentina. This is the most important branch. It has the most speakers and the richest cultural and literary history.

Words That Are Similar

Here are some similar words in different Quechuan languages:

| Ancash (I) | Wanka (I) | Cajamarca (II-A) | San Martin (II-B) | Kichwa (II-B) | Ayacucho (II-C) | Cusco (II-C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'one' | huk | suk, huk | suq | suk | shuk | huk | huk |

| 'two' | ishkay | ishkay | ishkay | ishkay | ishkay | iskay | iskay |

| 'ten' | ćhunka, chunka | ćhunka | ch'unka | chunka | chunka | chunka | chunka |

| 'sweet' | mishki | mishki | mishki | mishki | mishki | miski | misk'i |

| 'white' | yuraq | yulaq | yuraq | yurak | yurak | yuraq | yuraq |

| 'he gives' | qun | qun | qun | kun | kun | qun | qun |

| 'yes' | awmi | aw | ari | ari | ari | arí | arí |

Quechua and Aymara Languages

Quechua shares many words and some similar structures with the Aymara language. Because of this, some people thought they might be part of one "Quechumaran family." However, most experts now believe these similarities come from the languages influencing each other over a long time. Many shared words are very similar, sometimes even more so than words within Quechua itself.

Languages That Influenced Quechua

Quechua has been influenced by many other languages. These include Kunza, Leko, Mapudungun, Mochika, Uru-Chipaya, Zaparo, Arawak, Kandoshi, Muniche, Pukina, Pano, Barbakoa, Cholon-Hibito, Jaqi, Jivaro, and Kawapana.

Quechua Words in English

Quechua has borrowed many words from Spanish. Examples include piru (from pero, meaning "but"), bwenu (from bueno, meaning "good"), iskwila (from escuela, meaning "school"), waka (from vaca, meaning "cow"), and wuru (from burro, meaning "donkey").

Many Quechua words have also made their way into English (and French) through Spanish. These include:

The word lagniappe comes from the Quechuan word yapay, meaning "to increase" or "to add." It first went into Spanish, then into Louisiana French.

In Bolivia, people often use Quechua words even if they don't speak Quechua. For example, the Quechua word -ri is added to verbs. It can mean an action is done with kindness or, in a command, it can mean "please." So, in Bolivian Spanish, pásame ("pass me [something]") might become pasarime.

What Does "Quechua" Mean?

At first, the Spanish called the language of the Inca empire the lengua general, or "general tongue." The name quichua was first used in 1560 by Domingo de Santo Tomás. We don't know what native speakers called their language before the Spanish arrived.

There are two ideas about where the name Quechua came from. It might come from *qiĉ.wa, a native word that originally meant the "temperate valley" area in the Andes. This area was good for growing corn. The name could have referred to the people living there. Another idea is that early Spanish writers mentioned a group of people called Quichua in the Apurímac Region. Their name might have then been given to the whole language family.

The Spanish spellings Quechua and Quichua have been used in Peru and Bolivia since the 1600s. Today, people pronounce "Quechua Simi" in different ways.

Another name native speakers use for their language is runa simi, which means "language of man/people." This name also seems to have started during the colonial period.

How Quechua Sounds

Quechua has only three main vowel sounds: a, i, and u. These are pronounced like the vowels in Spanish. When these vowels are next to certain sounds (called uvular consonants), they change slightly.

Quechua has many consonant sounds. Some types of Quechua, like Cusco Quechua, have special sounds that are "puffed out" (aspirated) or made with a "pop" (ejective).

About 30% of modern Quechua words come from Spanish. Some Spanish sounds, like 'f', 'b', 'd', and 'g', are now also used in Quechua.

In most Quechua dialects, the stress (the part of the word you say loudest) is on the second-to-last syllable.

How Quechua is Written

Quechua has been written using the Roman alphabet since the Spanish conquest of Peru. But written Quechua is not used much because there are few printed materials in the language.

Until the 1900s, Quechua was written using Spanish spelling rules. For example, Inca or condor. This spelling is familiar to Spanish speakers. Most Quechua words that came into English used this older spelling.

In 1975, the Peruvian government created a new way to spell Quechua. This system uses w instead of hu for the 'w' sound. It also uses different letters for 'k' and 'q' sounds, which were both spelled with 'c' or 'qu' before. It also shows the "puffed out" and "popping" sounds in dialects like Cusco Quechua. This new spelling still used the five vowel sounds of Spanish.

In 1985, a different version of this system was adopted. It uses only three vowel sounds, which is how Quechua actually sounds.

These different spellings are still a big debate in Peru. Some people like the old system because it looks more like Spanish. They think it makes Quechua easier to learn for Spanish speakers. Others prefer the new system because it matches how Quechua sounds. They say teaching the five-vowel system can make it harder for children to read Spanish later.

Writers also differ in how they spell Spanish words used in Quechua. Sometimes they adapt them to the new Quechua spelling, and sometimes they keep the original Spanish spelling.

A linguist named Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino suggested a standard spelling for all Southern Quechua. This standard tries to combine features from the Ayacucho Quechua and Cusco Quechua dialects.

For example:

| English | Ayacucho | Cusco | Standard Quechua |

|---|---|---|---|

| to drink | upyay | uhyay | upyay |

| fast | utqa | usqha | utqha |

| to work | llamkay | llank'ay | llamk'ay |

| we (inclusive) | ñuqanchik | nuqanchis | ñuqanchik |

| (progressive suffix) | -chka- | -sha- | -chka- |

| day | punchaw | p'unchay | p'unchaw |

The old Spanish-based spelling is now against Peruvian law. The law says that place names in native languages should be spelled using the new, standardized alphabets. This helps make maps and other official documents consistent.

How Quechua Works (Grammar)

Quechua is an agglutinating language. This means words are built by adding many small parts (suffixes) to a main word. Each suffix adds a specific meaning. Quechua languages are very regular in how they add these parts.

Sentences usually follow a Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) order. This means the person or thing doing the action comes first, then the thing the action is done to, and finally the action itself.

Quechua verbs change to match both the subject (who is doing it) and the object (who it is done to). It also has a special way to show where information comes from (called evidentiality).

Pronouns

| Number | |||

| Singular | Plural | ||

| Person | First | Ñuqa | Ñuqanchik (inclusive)

Ñuqayku (exclusive) |

| Second | Qam | Qamkuna | |

| Third | Pay | Paykuna | |

In Quechua, there are seven pronouns. The first-person plural pronouns (like "we") can be either inclusive or exclusive. Inclusive means "we, including you." Exclusive means "we, but not including you."

Quechua also adds the suffix -kuna to make the second and third person singular pronouns plural. So, qam (you) becomes qam-kuna (you all). Pay (he/she/it) becomes pay-kuna (they).

Adjectives

Adjectives in Quechua always come before the nouns they describe. They do not change for gender or number.

Numbers

- Counting Numbers: ch'usaq (0), huk (1), iskay (2), kimsa (3), tawa (4), pichqa (5), suqta (6), qanchis (7), pusaq (8), isqun (9), chunka (10).

- Numbers above 10: chunka hukniyuq (11), chunka iskayniyuq (12), iskay chunka (20).

- Larger Numbers: pachak (100), waranqa (1,000), hunu (1,000,000), lluna (1,000,000,000,000).

- Order Numbers: To make order numbers (like "first," "second"), you add ñiqin after the counting number. For example, iskay ñiqin means "second." The only exception is for "first." You can say huk ñiqin or ñawpaq, which also means "the first" or "the oldest."

Nouns

Nouns in Quechua can have suffixes that show if they are plural, what their role is in the sentence (like subject or object), and who owns them. The possessive suffix usually comes before the plural suffix.

| What it shows | Suffix | Example | (translation) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| plural | -kuna | wasikuna | houses | |

| who owns it | my | -y, -: | wasiy, wasii | my house |

| your (singular) | -yki | wasiyki | your house | |

| his/her/its | -n | wasin | his/her/its house | |

| our (including you) | -nchik | wasinchik | our house (incl.) | |

| our (not including you) | -y-ku | wasiyku | our house (excl.) | |

| your (plural) | -yki-chik | wasiykichik | your (pl.) house | |

| their | -n-ku | wasinku | their house | |

| role in sentence | subject | – | wasi | the house (subj.) |

| object | -(k)ta | wasita | the house (obj.) | |

| with | -wan | wasiwan | with the house | |

| without | -naq | wasinaq | without the house | |

| for | -paq | wasipaq | for the house | |

| of | -p(a) | wasip(a) | of the house | |

| because of | -rayku | wasirayku | because of the house | |

| at | -pi | wasipi | at the house | |

| towards | -man | wasiman | towards the house | |

| including | -piwan, puwan | wasipiwan, wasipuwan | including the house | |

| up to | -kama, -yaq | wasikama, wasiyaq | up to the house | |

| through | -(rin)ta | wasinta | through the house | |

| from | -manta, -piqta | wasimanta, wasipiqta | from the house | |

| along with | -(ni)ntin | wasintin | along with the house | |

| first | -raq | wasiraq | first the house | |

| among | -pura | wasipura | among the houses | |

| only | -lla(m) | wasilla(m) | only the house | |

| than | -naw, -hina | wasinaw, wasihina | than the house | |

Adverbs

Adverbs can be made by adding -ta or -lla to an adjective. For example, allin (good) becomes allinta (well). They can also be made by adding suffixes to words like chay (that) to make chaypi (there).

An interesting thing about Quechua adverbs is that qhipa means both "behind" and "future." And ñawpa means "ahead" and "past." This is different from European languages. For Quechua speakers, we move backward into the future (because we can't see it). We face the past (because we remember it).

Verbs

Verbs in their basic form end with -y (e.g., much'ay means "to kiss"). Quechua verbs have different endings for different tenses (like present, past, future) and for who is doing the action.

The suffixes usually show the subject (who is doing the action). But a suffix can also show the object (who the action is done to). For example, -wa- means "me."

Grammar Particles

Particles are small words that don't change. They don't take suffixes. They are not very common. The most common ones are arí (yes) and mana (no). Mana can take some suffixes to make its meaning stronger. Other particles include yaw (hey, hi) and some words borrowed from Spanish, like piru (from Spanish pero, meaning "but").

Showing Where Information Comes From

Quechuan languages have special parts of words that show where information comes from. This is called evidentiality. It tells you how the speaker knows something. There are three main ways to show this:

| -m(i) | -chr(a) | -sh(i) |

|---|---|---|

| Direct evidence | Inferred; guess | Reported; heard from someone else |

- -m(i) (Direct evidence): This means the speaker knows something for sure, usually because they saw or experienced it themselves.

* Example: ñawi-i-wan-mi lika-la-a (I saw them with my own eyes.)

- -chr(a) (Inferred; guess): This means the speaker is guessing or inferring something. They are not completely sure.

* Example: kuti-mu-n'a-qa-chr ni-ya-ami (I think they will probably come back.)

- -sh(i) (Reported; hearsay): This means the speaker heard the information from someone else. It's like saying "I was told..." or "They say..."

* Example: shanti-sh prista-ka-mu-la ((I was told) Shanti borrowed it.)

These markers usually attach to the first important word in a sentence. They can also attach to a word that the speaker wants to emphasize.

In Quechua culture, using these markers correctly is very important. It shows that you are precise and honest about your information. If someone doesn't use them correctly, it can make others question their honesty or even their mental health. This shows how important it is in the culture to state where your information comes from.

Quechua in Books and Media

Like other ancient cultures, the Andes region had many stories and poems. After the Spanish arrived, some of these were written down using Latin letters. For example, some Quechua poems from Inca times are found in Spanish history books. The most important old Quechua text is the Huarochirí Manuscript (1598). It describes the myths and religion of the Huarochirí valley. Some people compare it to "an Andean Bible."

From the mid-1600s, many Quechua plays were written. Some were about the Inca era, while most were religious plays inspired by Europe. Famous plays include Ollantay and plays about the death of Atahualpa. Juan de Espinosa Medrano wrote several plays in Quechua. Poems were also written during this time.

Christian books were also published in Quechua. In 1583, a church council in Lima published Christian texts, including a catechism (a book of religious teachings) in Spanish, Quechua, and Aymara.

Plays and poems continued to be written in the 1800s and 1900s. In the 1900s, more prose (regular writing, not poetry or plays) was published. Much of the 20th-century Quechua literature is made up of traditional folk stories and oral tales.

Demetrio Túpac Yupanqui wrote a Quechuan version of Don Quixote.

Quechua in Media

A news broadcast in Quechua, called "Ñuqanchik" (all of us), started in Peru in 2016.

Many musicians from the Andes write and sing in their native languages, including Quechua and Aymara. Some famous groups are Los Kjarkas, Kala Marka, J'acha Mallku, Savia Andina, Wayna Picchu, Wara, Alborada, and Uchpa.

There are also several Quechua and Quechua-Spanish bloggers. You can find a Quechua language podcast too.

The 1961 Peruvian film Kukuli was the first movie spoken in the Quechua language.

In the 1977 science fiction film Star Wars, the alien character Greedo speaks a changed form of Quechua.

See also

In Spanish: Lenguas quechuas para niños

In Spanish: Lenguas quechuas para niños

- Languages of Peru

- Andes

- Quechua People

- Aymara language

- List of English words of Quechuan origin

- Quechuan and Aymaran spelling shift

- South Bolivian Quechua

- Sumak Kawsay

Sources

- Rolph, Karen Sue. Ecologically Meaningful Toponyms: Linking a lexical domain to production ecology in the Peruvian Andes. Doctoral Dissertation, Stanford University, 2007.

- Adelaar, Willem. The Languages of the Andes. With the collaboration of P.C. Muysken. Cambridge language survey. Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN: 978-0-521-36831-5

- Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. Lingüística Quechua, Centro de Estudios Rurales Andinos 'Bartolomé de las Casas', 2nd ed. 2003

- Cole, Peter. "Imbabura Quechua", North-Holland (Lingua Descriptive Studies 5), Amsterdam 1982.

- Cusihuamán, Antonio, Diccionario Quechua Cuzco-Collao, Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos "Bartolomé de Las Casas", 2001, ISBN: 9972-691-36-5

- Cusihuamán, Antonio, Gramática Quechua Cuzco-Collao, Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos "Bartolomé de Las Casas", 2001, ISBN: 9972-691-37-3

- Mannheim, Bruce, The Language of the Inka since the European Invasion, University of Texas Press, 1991, ISBN: 0-292-74663-6

- Rodríguez Champi, Albino. (2006). Quechua de Cusco. Ilustraciones fonéticas de lenguas amerindias, ed. Stephen A. Marlett. Lima: SIL International y Universidad Ricardo Palma. Lengamer.org

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra. Evidentiality. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. Print.

- Floyd, Rick. The Structure of Evidential Categories in Wanka Quechua. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1999. Print.

- Hintz, Diane. "The evidential system in Sihuas Quechua: personal vs. shared knowledge" The Nature of Evidentiality Conference, The Netherlands, 14–16 June 2012. SIL International. Internet. 13 April 2014.

- Lefebvre, Claire, and Pieter Muysken. Mixed Categories: Nominalizations in Quechua. Dordrecht, Holland: Kluwer Academic, 1988. Print.

- Weber, David. "Information Perspective, Profile, and Patterns in Quechua." Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology. Ed. Wallace L. Chafe and Johanna Nichols. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Pub, 1986. 137–55. Print.

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |