South Bolivian Quechua facts for kids

Quick facts for kids South Bolivian Quechua |

|

|---|---|

| Uralan Buliwya runasimi | |

| Native to | Bolivia; a few in Argentina, Chile |

| Ethnicity | Quechuas, Kolla |

| Native speakers | 2,785,120 (date missing)e18 |

| Language family |

Quechuan

|

| Official status | |

| Official language in | |

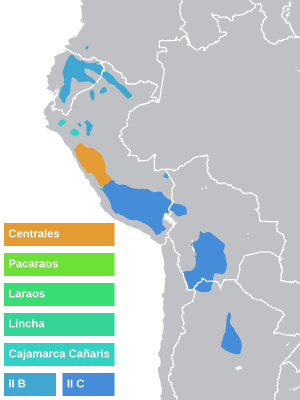

The four branches of Quechua. South Bolivian Quechua is a dialect of Southern Quechua (II-C).

|

|

South Bolivian Quechua, also called Central Bolivian Quechua, is a language spoken in Bolivia. You can also find speakers in nearby parts of Argentina, where it's known as Colla. It's important not to mix it up with North Bolivian Quechua. That language is spoken in a different part of Bolivia and sounds quite different.

About 2.3 to 2.8 million people speak South Bolivian Quechua. This makes it the most spoken native language in Bolivia. It has slightly more speakers than Aymara, which has about 2 million speakers in Bolivia.

Contents

What is South Bolivian Quechua?

South Bolivian Quechua is part of the Southern group of Quechuan languages. This means it's closely related to other Southern Quechua languages. These include Ayacucho Quechua and especially Cuzco Quechua language, both spoken in Peru.

The Quechua language family is very diverse. Many of its languages are so different that speakers can't understand each other. This is why language experts see Quechua as a family of languages, not just one language with many dialects. Experts believe all Quechuan languages came from one ancient language called Proto-Quechua. But they still debate how modern Quechuan languages developed.

Where is it Spoken?

South Bolivian Quechua has slightly different versions, or dialects, across Bolivia. These dialects are found in areas like Chuquisaca, Cochabamba, Oruro, Potosi, and Sucre. You can also hear it in Northwest Jujuy, Argentina. A small number of people, about 8,000, still speak it in Chile. Santiagueño Quechua in Argentina is also related, and seems to have come from South Bolivian Quechua.

How is the Language Doing?

Quechua is an official language in Bolivia. It is one of the 36 native languages recognized in the country's constitution. South Bolivian Quechua has many speakers compared to other native languages. However, it faces challenges. The Spanish language, which is often seen as more important, can make Quechua seem less valuable.

Also, the many different Quechua dialects have their own ways of speaking and thinking. This makes it hard for leaders to create plans for all Quechua speakers at once. Each Quechua community might need different support for its language.

Is it in Danger?

The Ethnologue website says South Bolivian Quechua is "developing." This means people use it a lot, and some books are written in a standard form. But this use is not yet widespread. However, UNESCO's Atlas of Endangered Languages calls South Bolivian Quechua "vulnerable." This means most children in a community speak it at home with family. But they might not use it in other places.

In recent years, there's been a big push to help Quechua and other native languages. This is partly because more tourists visit, which makes people proud of their culture. People are working to make the Quechua language and culture more respected. In Bolivia, many leaders want to teach Quechua and other native languages like Aymara in all public schools and government offices. But these efforts sometimes face problems, and it's not clear yet if they will stop the language from declining.

How Quechua Words are Built

South Bolivian Quechua is an agglutinative and polysynthetic language. This means words are built by adding many small parts, called suffixes, to a base word. Because of this, words in South Bolivian Quechua can become very long.

Words in this language only use suffixes. They don't use other types of word parts at the beginning or in the middle. These suffixes are also very regular. They usually only change a little to keep the word sounding good.

Words are built in a specific order:

- Base word + suffixes that change the word's meaning + suffixes that show grammar + small words added to the end.

How Words Change Meaning

South Bolivian Quechua has many suffixes that change a word's type. For example, they can turn a noun into a verb, or a verb into an adjective. Here are some examples:

Note: -y is the ending that makes a verb mean "to do something."

- -cha (makes something happen): wasi "house", wasi-cha-y "to build a house"

- -naya (to feel like doing something): aycha "meat", aycha-naya-y "to feel like eating some meat"

- -ya (to become something): wira "fat", wira-ya-y "to get fat, put on weight"

- -na (something that must be done): tiya "sit", tiya-na "seat, chair"

- -yuq (someone who has something): wasi "house", wasi-yuq "householder"

- -li (makes an adjective from a verb): mancha "fear", mancha-li "cowardly, fearful"

Some suffixes can act in different ways. For example, the suffix ‘’-chi’’ can sometimes change a verb's meaning directly:

- mik"u-chi- "make (someone) eat"

- puri-chi- "make (someone) walk"

But other times, it can create a new word:

- puma wañu-chi "puma hunter" (someone who causes pumas to die)

- wasi saya-chi "house builder, carpenter" (someone who causes houses to stand)

How Words Show Grammar

Verbs

Verbs in South Bolivian Quechua use suffixes to show different things. These include how sure someone is about something, who is doing the action, and when the action happens.

The language has many suffixes that show how something is said or felt. Some examples are:

- -ra "to undo"; wata-ra- "unknot, untie"

- -naya "to intend to, about to"; willa-naya- "act as if to tell"

- -ysi "to help someone"; mik”u-ysi-y "help him eat"

- -na "have to, be able to" (must do); willa-na- "have to tell"

- -pu "for someone else" (for their benefit); qu-pu-y "give it to him"

Some of these suffixes can also change the word's meaning, like -naya and -na when used with words that are not verbs.

Suffixes also show who is doing the action (subject) and who the action is for (object). For example, -wa is used for a first-person object (me/us), and -su for a second-person object (you).

Nouns

Nouns in South Bolivian Quechua can be made plural by adding -kuna. For example, yan (road) becomes yankuna (roads). However, many speakers use -s, like in Spanish, when a noun ends in a vowel. So, wasi (house) becomes wasis (houses).

There's also a suffix -ntin that means "together with." For example, alqu michi-ntin means "the dog, together with the cat."

Nouns also use suffixes to show who owns something. These suffixes change based on who owns it and if it's one person or many.

Other Word Types

Pronouns (like "he," "she," "it") in Quechua don't have suffixes for who is speaking. But they do have suffixes to show if they are singular or plural.

Adjectives (words that describe nouns) can be made into superlatives (like "best" or "tallest") with the suffix -puni. For example, kosa "good"; kosa-puni "good above all others, best."

Suffixes for Any Word

Some suffixes in South Bolivian Quechua can be used with almost any type of word. They are usually found at the very end of the word. Here are some examples:

- -ri "please, nicely, with delight" (makes it polite)

- -pis "even though, even if, and, also" (adds something)

- -chu "is it so?" (used for questions)

- -chus "if, maybe" (shows doubt)

Repeating Words or Parts of Words

Repeating words or parts of words, called Reduplication, is used a lot in Quechua. It can change the meaning of a word:

- llañuy "thin"; llañuy llañuy "very thin"

- wasi "house"; wasi wasi "settlement, collection of houses"

- rumi "stone"; rumi rumi "rocky"

Sometimes, sounds that describe something can be repeated and have suffixes added:

- taq "sound of hammer blow"; taq-taq-ya-y "to hit with a hammer"

How Sentences are Built

Word Order in Sentences

The usual word order in South Bolivian Quechua is Subject-Object-Verb (SOV). This means the person or thing doing the action comes first, then the person or thing receiving the action, and finally the action itself. For example, "The boy the ball kicked."

However, because nouns have special endings that show their role in the sentence, the word order can be very flexible. People often change the order to emphasize certain parts of the sentence. For example, all these sentences mean "Atahuallpa had Huascar killed":

- Atawallpa sipi-chi-rqa Waskar-ta.

- Atawallpa Waskar-ta sipi-chi-rqa.

- Waskara-ta Atawallpa sipi-chi-rqa.

- Waskar-ta sipi-chi-rqa Atawallpa.

One rule that always stays the same is that words that describe nouns must come right before the noun they describe. For example, "big house" would be "big house" not "house big."

Noun Endings for Roles

Nouns in South Bolivian Quechua have special endings, called case markers, that show their job in the sentence. Here are some examples:

- -ta: shows the direct object (the thing the action is done to)

- -man: shows direction (to, toward)

- -pi: shows location (in, at, on)

- -wan: shows what tool was used (with, by means of)

- -paq: shows purpose (for, in order to)

If a noun doesn't have one of these endings, it's usually the subject (the person or thing doing the action).

Passive Voice

The passive voice is used when the action is done to the subject, rather than the subject doing the action. For example, "The ball was kicked by the boy." In Quechua, passive sentences use suffixes like -sqa on the verb. They also use -manta "from, by" for the person doing the action, and -wan "with" for the tool used.

- Chay runa alqu-manta k"ani-sqa "That man was bitten by the dog" (The dog bit the man)

- Runa rumi-wan maqa-sqa "The man was hit with a rock" (Someone hit the man with a rock)

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |