Revolt of the Comuneros facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Revolt of the Comuneros |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Comuneros rebels | Royalist Castilians | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Juan López de Padilla Juan Bravo Francisco Maldonado María Pacheco Antonio de Acuña Pedro Girón |

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor Adrian of Utrecht (Regent of Castile) Íñigo Fernández (Constable of Castile) Fadrique Enríquez (Admiral of Castile) |

||||||

| 1February 3, 1522 is also used as an end date; see 1522 revolt. | |||||||

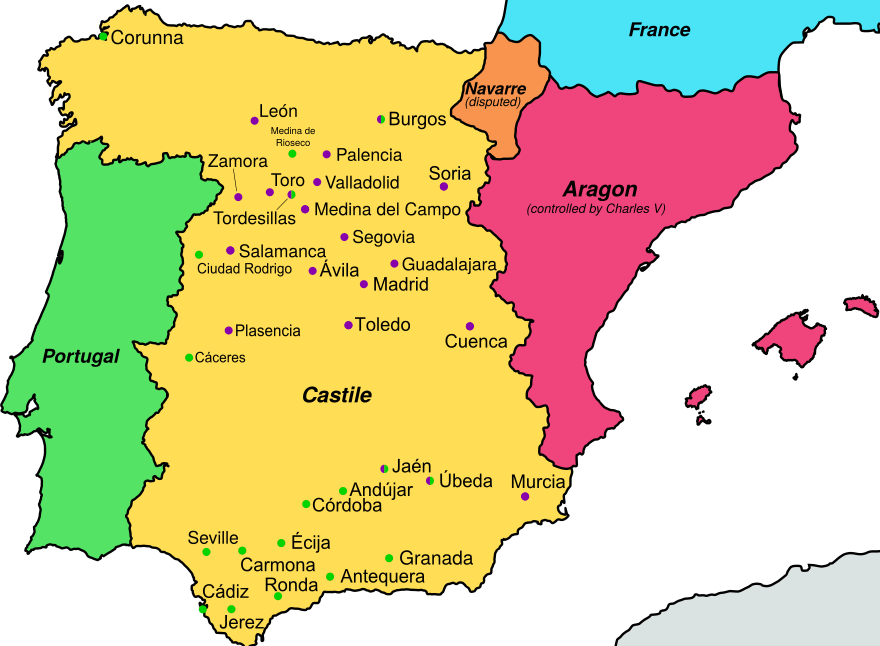

The Revolt of the Comuneros was a big uprising in Castile, a part of Spain, between 1520 and 1521. Citizens rebelled against their new king, King Charles I, and his government. At its strongest, the rebels controlled important cities like Valladolid, Tordesillas, and Toledo.

This revolt happened because of problems in Castile after Queen Isabella I died in 1504. Her daughter, Joanna, became queen. But because Joanna was not well, her father, King Ferdinand II of Aragon, ruled as a regent (someone who governs for a king or queen).

When Ferdinand died in 1516, Joanna's 16-year-old son, Charles, became co-ruler of Castile and Aragon. Charles had grown up in the Netherlands and didn't know much Castilian. He arrived in Spain with many foreign nobles. This made the Spanish people, especially the powerful families, worried about losing their influence.

In 1519, Charles was chosen to be the Holy Roman Emperor. He left Spain in 1520, leaving a Dutch cardinal, Adrian of Utrecht, in charge. Soon, people in cities started rioting. Local city councils, called Comunidades, took power. The rebels even wanted Charles's mother, Queen Joanna, to rule instead. The rebellion also became about helping peasants against rich nobles.

On April 23, 1521, the king's supporters badly defeated the Comuneros at the Battle of Villalar. The next day, rebel leaders Juan López de Padilla, Juan Bravo, and Francisco Maldonado were executed. The rebel army fell apart. Only the city of Toledo kept fighting, led by María Pacheco, until October 1521.

Historians still debate what this revolt was truly about. Some say it was one of the first modern revolutions, fighting for democracy and freedom. Others see it as a typical rebellion against high taxes and foreign control. Today, April 23 is celebrated as Castile and León Day, honoring the Comuneros.

Contents

Why the Revolt Started

Problems had been building up for many years before the Revolt of the Comuneros. In the late 1400s, Spain saw big changes in politics, money, and society. New businesses grew in cities, offering ways to gain power and wealth without being born into a noble family. These city leaders helped Ferdinand and Isabella make the government stronger. They balanced the power of the rich nobles and the church.

But after Queen Isabella I died in 1504, this balance broke down. The government in Castile became weak and corrupt. Queen Joanna's husband, Philip I, ruled for a short time. Then Archbishop Cisneros was regent, followed by Isabella's widower, Ferdinand II of Aragon. Ferdinand's claim to rule Castile was weak after Isabella's death. But there were no other good options, as Queen Joanna was not able to rule alone.

The powerful nobles in Castile took advantage of the weak government. They illegally expanded their lands and power using their own armies. The government did nothing to stop them. Because of this, towns started making agreements to protect each other, rather than relying on the national government.

Spain's money situation was also bad. The government had forced out the Jews in 1492 and the Muslims of Granada in 1502. These actions hurt many profitable businesses. Ferdinand and Isabella had to borrow money for wars, and Spain's military costs kept growing. Many soldiers were needed to keep peace in Granada and protect against pirate attacks. Also, Ferdinand had taken over Navarre in 1512, needing more soldiers there. Very little money was left for the royal army in Castile itself. The corruption in the government made the money problems even worse.

Charles Becomes King

In 1516, Ferdinand died. The next in line was Ferdinand and Isabella's grandson, Charles. He became King Charles I of both Castile and Aragon, ruling with his mother, Queen Joanna I. Joanna, who was kept in Tordesillas, also became Queen of Aragon. But she remained confined and had little power.

Charles grew up in Flanders and barely spoke Castilian. People were unsure about him, but hoped he would bring stability. When the new king arrived in late 1517, his Flemish (from Flanders) friends and advisers took important jobs in Castile. Charles only trusted people he knew from the Netherlands. One shocking appointment was making 20-year-old William de Croÿ the Archbishop of Toledo. This was a very important position, once held by the former regent, Archbishop Cisneros.

After six months, many people, rich and poor, were unhappy. Even some monks spoke out against the king's fancy court, the foreign advisers, and the nobles. As unrest grew, Charles's grandfather, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, died in 1519. A new emperor had to be chosen. Charles spent a lot of money to win this election, competing with King Francis I of France. Charles I won and became Emperor Charles V. He then prepared to go to Germany to take control of his new lands.

New Taxes and Unrest

Charles had already spent a lot of money on his court and to win the election. He needed to raise taxes to cover these debts. But any new taxes had to be approved by the Cortes, Castile's parliament. So, in March 1520, Charles called the Cortes to meet in Santiago de Compostela. Charles tried to limit the Cortes' power and bribe representatives to vote his way. But support for the opposition grew. Representatives demanded that their complaints be heard before any new tax was approved.

A group of church leaders wrote a protest against the king. They said new taxes should be refused. They also said Castile should be put first, not the foreign empire. And if the king ignored his people, the Comunidades (communities) should protect the kingdom. This was the first time the word comunidades was used for independent citizens. This name stuck for the councils that formed later.

Most Cortes members in Santiago planned to vote against the king's taxes. So, Charles stopped the meeting on April 4. He called them again in Corunna on April 22, where he finally got his taxes approved. On May 20, he sailed to Germany. He left his old teacher, Adrian of Utrecht, as regent of Spain. Adrian later became Pope Adrian VI.

The Revolt Begins

Toledo Rebels First

In April 1520, Toledo was already restless. The city council had protested Charles's plan to become Holy Roman Emperor. They worried about the costs to Castile and if Castile would become just a small part of a big empire. The situation exploded when the government ordered the most rebellious city council members to leave. The king wanted to replace them with people he could control.

On April 15, as the councilors prepared to leave, a large crowd rioted. They drove out the king's officials instead. Citizens elected a new committee, calling themselves a Comunidad. Juan López de Padilla and Pedro Laso de la Vega led them. On April 21, the remaining royal officials were forced out of the Alcázar of Toledo fortress.

After Charles left for Germany, riots spread in cities across central Castile. This happened especially after the representatives who voted for the new taxes returned home. Segovia had some of the first and most violent incidents. On May 30, a mob killed two officials and the city's representative who voted for the taxes. Similar events happened in Burgos and Guadalajara. Other cities like León, Ávila, and Zamora had smaller problems.

Rebels Ask Other Cities for Help

With widespread anger, Toledo's council suggested an emergency meeting to other cities with a vote in the Cortes. They proposed five main goals:

- Cancel the new taxes from the Cortes of Corunna.

- Go back to the old system of local tax collection.

- Only Castilians should get official jobs and church positions.

- Stop money from leaving the kingdom to pay for foreign wars.

- Choose a Castilian to lead the kingdom when the king was away.

These demands, especially the first two, quickly became popular. Some even talked about replacing the king. Toledo's leaders thought about making Castilian cities independent, like free cities in Italy. Other ideas included keeping the monarchy but replacing Charles with his mother, Queen Joanna, or his Castilian-born brother, Ferdinand. With these ideas, the revolt became a bigger revolution, not just a tax protest. Many cities stopped sending taxes to the Royal Council and started governing themselves.

Revolt Spreads

Fight in Segovia

The situation became more like a war on June 10. Rodrigo Ronquillo was sent by the Royal Council to investigate the murder of Segovia's representative. But Segovia refused to let him in. Ronquillo couldn't attack a city of 30,000 people with his small force. So, he tried to stop food and supplies from entering Segovia. The people of Segovia, led by militia leader Juan Bravo, united around their Comunidad.

Segovia asked Toledo and Madrid for help against Ronquillo's army. The cities sent their militias, led by Juan López de Padilla and Juan de Zapata. They won the first major fight between the king's forces and the rebels.

The Junta of Ávila

Other cities followed Toledo and Segovia, removing their old governments. A new rebel parliament, called La Santa Junta de las Comunidades ("Holy Assembly of the Communities"), met for the first time in Ávila. They declared themselves the true government, replacing the Royal Council. Padilla was named Captain-General, and troops were gathered. At first, only four cities sent representatives: Toledo, Segovia, Salamanca, and Toro.

Burning of Medina del Campo

Facing the situation in Segovia, Regent Cardinal Adrian of Utrecht decided to use the royal cannons, which were in nearby Medina del Campo. He planned to take Segovia and defeat Padilla. Adrian ordered his commander, Antonio de Fonseca, to seize the cannons. Fonseca arrived on August 21 in Medina. But he met strong resistance from the townspeople, as Medina had close trade ties with Segovia.

Fonseca ordered a fire to distract the rebels, but it got out of control. Much of the town was destroyed, including a monastery and a trade warehouse. Fonseca had to pull back his troops. This event was a disaster for the government's public image. Uprisings happened all over Castile, even in cities that had been neutral, like Castile's capital, Valladolid.

When Valladolid joined the rebels, it shook the government's power. New members joined the Junta of Ávila, and the Royal Council looked bad. Adrian had to flee to Medina de Rioseco as Valladolid fell. The royal army, with many soldiers unpaid, started to break apart.

The Junta of Tordesillas

The Comunero army became well organized, combining militias from Toledo, Madrid, and Segovia. After hearing about Fonseca's attack, the Comunero forces went to Medina del Campo. They took the cannons that Fonseca's troops had failed to get. On August 29, the Comunero army reached Tordesillas. Their goal was to declare Queen Joanna the only ruler.

The Junta moved from Ávila to Tordesillas at the Queen's request. They invited cities that hadn't sent representatives yet to join. Thirteen cities were represented in the Junta of Tordesillas. These included Burgos, Soria, Segovia, Ávila, Valladolid, León, Salamanca, Zamora, Toro, Toledo, Cuenca, Guadalajara, and Madrid. Only four cities from Andalusia in the south did not attend.

Since most of the kingdom was represented, the Junta renamed itself the Cortes y Junta General del Reino ("General Assembly of the Kingdom"). On September 24, 1520, the Queen, for the only time, led the Cortes meeting.

The representatives met with Queen Joanna. They explained that the Cortes wanted to declare her the true ruler and bring back stability. The next day, September 25, the Cortes announced they would use force if needed. They also promised to help any city that was threatened. On September 26, the Cortes of Tordesillas declared itself the new legal government and rejected the Royal Council. All the cities represented swore to defend each other by September 30. The rebel government now had a clear structure and could act freely. The Royal Council was still weak and confused.

Where the Rebellion Was Strongest

The Comuneros were strongest in the central plateau of Spain. They also had support in a few other places like Murcia. The rebels tried to spread their ideas to the rest of the kingdom, but didn't have much success. There were few rebellions in Galicia in the northwest or in Andalusia in the south.

Comunidades were set up in southern cities like Jaén, Úbeda, and Baeza. But over time, these cities returned to the king's side. Murcia stayed with the rebels, but didn't work closely with the Junta. The rebellion there was more like the nearby Revolt of the Brotherhoods in Valencia. In Extremadura to the southwest, Plasencia joined the Comunidades. But it was surrounded by cities loyal to the king, like Ciudad Rodrigo and Cáceres.

There was a clear link between bad economic times and the rebellion. Central Castile had suffered from poor farming and other problems under the Royal Council. But Andalusia was doing well with its sea trade. Leaders in Andalusia also worried that a civil war would cause the Moriscos (former Muslims who converted to Christianity) in Granada to revolt.

Organizing and Fighting

The Comuneros faced their first political setbacks in October 1520. Their attempt to use Queen Joanna to make their rule seem legal didn't work. She blocked their plans and refused to sign any orders. Because of this, some Comuneros started to disagree, especially in Burgos.

The royalists soon learned that Burgos was unsure. The Constable of Castile talked with Burgos's government. The Royal Council gave Burgos many important promises if they left the Junta. Burgos agreed and left the Comuneros.

After this, the Royal Council hoped other cities would follow Burgos and leave the Comuneros peacefully. Valladolid, which used to be the king's main city, was expected to switch. But too many of the king's supporters had left city politics. So, Valladolid remained under rebel control. The Admiral of Castile kept trying to convince the Comuneros to return to the king's side. He wanted to avoid a violent fight. This peaceful approach hid the fact that the royal side was very short on money.

During October and November 1520, both sides knew that a military fight was coming. They worked hard to raise money, recruit soldiers, and train their troops. The Comuneros organized their militias in the main cities and collected new taxes from the countryside. They also tried to stop wasteful spending, checking their treasurers and firing those who were corrupt. The royal government, which had lost much of its income due to the revolt, borrowed money from Portugal and from rich Castilian bankers. These bankers felt more confident after Burgos switched its loyalty.

Battle of Tordesillas

Leaders Disagree

Over time, the city of Toledo and its leader, Juan López de Padilla, lost some influence within the Junta. However, Padilla remained popular among the common people. Two new leaders appeared among the Comunidades: Pedro Girón and Antonio Osorio de Acuña. Girón was a powerful noble who supported the Comuneros. He joined the rebellion because Charles had refused to give him an important title a year before the war. Antonio de Acuña was the Bishop of Zamora. Acuña also led the Comunidad in Zamora and its army, which included over 300 priests.

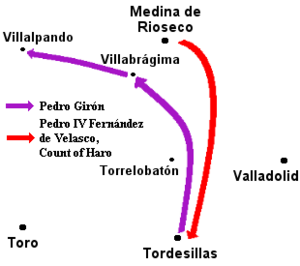

On the royalist side, the nobles couldn't agree on how to fight. Some wanted to attack the rebels directly. Others, like the Constable of Castile, preferred to wait and build defenses. The Admiral of Castile wanted to keep talking and try all peaceful options first. But patience was running out. Armies were expensive to keep once they were gathered. In late November 1520, both armies took positions between Medina de Rioseco and Tordesillas. A fight seemed unavoidable.

Royalists Take Tordesillas

Pedro Girón led the Comunero army towards Medina de Rioseco, following the Junta's orders. Girón set up his base in Villabrágima, a town only 8 kilometers (5 miles) from the royalist army. The royalists took over nearby villages to cut off the Comuneros' communication lines.

This continued until December 2. Girón, seemingly thinking the royal army would stay put, moved his forces west to the small town of Villalpando. The town surrendered the next day without a fight, and the troops began looting the nearby estates. However, by moving, the Comuneros left the path to Tordesillas completely open. The royal army took advantage of this mistake. They marched by night on December 4 and captured Tordesillas the next day. The small rebel force there was easily defeated.

Taking Tordesillas was a major loss for the Comuneros. They lost Queen Joanna, and with her, their claim to be the rightful government. Also, thirteen representatives of the Junta were captured, though others escaped. Morale among the rebels dropped. Many people blamed Pedro Girón for moving the troops out of position and for not trying to retake Tordesillas. Girón had to resign and left the war.

Events of December and January

Rebels Reorganize

After losing Tordesillas, the Comuneros gathered again in Valladolid. The Junta met on December 15, but only eleven cities were represented, down from fourteen. Soria and Guadalajara's representatives didn't return, and Burgos had left earlier. Valladolid became the rebels' third capital, after Ávila and Tordesillas.

The army's situation was worse, with many soldiers leaving in Valladolid and Villalpando. This forced the rebels to recruit more people, especially in Toledo, Salamanca, and Valladolid. With new recruits and Juan de Padilla's arrival in Valladolid, the rebel army was rebuilt, and morale improved. By early 1521, the Comuneros prepared for a full-scale war, despite disagreements within the movement. Some wanted a peaceful solution, while others favored continuing the war. Those who wanted war were split between two plans: take Simancas and Torrelobatón, a smaller goal supported by Pedro Laso de la Vega; or attack Burgos, which Padilla preferred.

Fighting in Palencia and Burgos

In northern Castile, the rebel army started operations led by Antonio de Acuña, the bishop of Zamora. On December 23, the Junta ordered them to try and start a rebellion in Palencia. Their job was to remove royalists, collect taxes for the Junta, and set up a government that supported the Comuneros. Acuña's army raided the area around Dueñas, collecting over 4,000 ducats and inspiring the peasants. He returned to Valladolid in early 1521. Then, on January 10, he went back to Dueñas to start a big attack against the nobles of Tierra de Campos. The nobles' lands and properties were completely destroyed.

In mid-January, Pedro de Ayala, Count of Salvatierra, joined the Comuneros. He formed an army of about two thousand men who began raiding northern Castile. Nearby, Burgos was waiting for Cardinal Adrian to keep his promises after they joined the royalist side two months earlier. The slow response made the city unhappy. Ayala and Acuña knew this. They decided to attack Burgos, Ayala from the north and Acuña from the south. They also tried to weaken the city's defenses by encouraging the people of Burgos to revolt.

Rebel Campaigns of Early 1521

Padilla's Next Move

After failing to capture Burgos, Padilla decided to return to Valladolid. Acuña chose to continue his attacks on noble lands around Tierra de Campos. With these actions, Acuña aimed to destroy or take over the homes of important nobles. The rebels were now completely against the feudal system, where nobles controlled large estates and the people living on them. This became a key part of the second phase of the rebellion.

After recent losses, Padilla knew the Comuneros needed a victory to boost their spirits. He decided to take Torrelobatón and its castle. Torrelobatón was a strong fortress between Tordesillas and Medina de Rioseco, and very close to Valladolid. Taking it would give the rebels a great base for military operations and remove a threat to Valladolid.

Battle of Torrelobatón

The siege of Torrelobatón began on February 21, 1521. The town was outnumbered but resisted for four days, thanks to its strong walls. On February 25, the Comuneros entered the town and looted it heavily as a reward for their troops. Only churches were spared. The castle held out for two more days. The Comuneros then threatened to hang all the people inside. At that point, the castle surrendered. The defenders managed to save half of the goods inside the castle, preventing more looting.

The victory at Torrelobatón raised the rebels' spirits, just as Padilla hoped. It also worried the royalists about the rebel advance. The nobles' trust in Cardinal Adrian was shaken again, as they accused him of doing nothing to prevent the loss of Torrelobatón. The Constable of Castile began sending troops to the Tordesillas area to stop the rebels from advancing further.

Despite the new excitement among the rebels, they decided to stay in their positions near Valladolid. They did not press their advantage or launch a new attack. This caused many soldiers to return home, tired of waiting for pay and new orders. This was a problem for the Comunero forces throughout the war. They had only a small number of full-time soldiers, and their militias were constantly changing. A serious attempt to negotiate a peaceful end to the war was made by the moderates. But extremists on both sides ruined the talks.

In the north, after the failed attack on Burgos in January, the Count of Salvatierra continued his campaign. He tried to start an uprising in Merindades, the Constable of Castile's home region. He attacked Medina de Pomar and Frías.

Acuña's Southern Campaign

William de Croÿ, the young Flemish Archbishop of Toledo appointed by Charles, died in January 1521. In Valladolid, the Junta suggested that Antonio de Acuña become a candidate for the position.

Acuña left for Toledo in February with a small force. He traveled south, announcing his claim to the archdiocese in every village he passed. This made the common people excited, and they cheered him. But it made the rich nobles suspicious. They feared Acuña might attack their lands, as he did in Tierra de Campos. The Marquis of Villena and Duke of Infantado contacted Acuña. They convinced him to sign a promise of neutrality, meaning they wouldn't fight each other.

Acuña soon had to face Antonio de Zúñiga, who was the commander of the royalist army in the Toledo area. Zúñiga was a prior in the Knights of St. John. Acuña learned that Zúñiga was near Corral de Almaguer and fought him near Tembleque. Zúñiga drove off the rebel forces. Then he launched his own attack between Lillo and El Romeral, badly defeating Acuña. Acuña, who liked to promote himself, tried to play down the loss. He even claimed he had won the fight.

Undeterred, Acuña continued to Toledo. He arrived at the Zocodover Plaza in the city center on March 29, 1521, which was Good Friday. The crowd gathered around him and took him directly to the cathedral, claiming the archbishop's seat for him. The next day, he met with María Pacheco, Juan de Padilla's wife and the unofficial leader of the Toledo Comunidad while her husband was away. A brief rivalry started between them, but they resolved it after trying to make peace.

Once settled in the archdiocese of Toledo, Acuña began recruiting any men he could find, from 15 to 60 years old. After royalist troops burned the town of Mora on April 12, Acuña returned to the countryside with about 1,500 men. From Yepes, he raided and attacked royalist-controlled rural areas. He first attacked and looted Villaseca de la Sagra. Then he faced Zúñiga again in a battle near the Tagus river in Illescas, which had no clear winner. Small fights near Toledo continued until news of Villalar ended the war.

Battle of Villalar

In early April 1521, the royalist side decided to combine their armies and threaten Torrelobatón. The Constable of Castile moved his troops (including soldiers from Navarre) southwest from Burgos to meet the Admiral's forces near Tordesillas. Meanwhile, the Comuneros reinforced their troops at Torrelobatón, which was not as safe as they wanted. Their forces were losing soldiers, and the royalist cannons would make Torrelobatón's castle vulnerable. Juan López de Padilla thought about moving to Toro for more soldiers in early April, but he hesitated. He delayed his decision until the early hours of April 23. This lost valuable time and allowed the royalists to unite their forces in Peñaflor.

The combined royalist army chased the Comuneros. Again, the royalists had a big advantage in cavalry (soldiers on horseback). Their army had 6,000 foot soldiers and 2,400 cavalry. Padilla's army had 7,000 foot soldiers and only 400 cavalry. Heavy rain slowed Padilla's foot soldiers more than the royalist cavalry. It also made the rebels' 1,000 arquebusiers (soldiers with early firearms) almost useless. Padilla hoped to reach the safety of Toro and the high ground of Vega de Valdetronco. But his foot soldiers were too slow. He fought the attacking royalist cavalry near the town of Villalar. The cavalry charges broke up the rebel lines, and the battle became a massacre. About 500–1,000 rebels were killed, and many others ran away.

The three most important rebel leaders were captured: Juan López de Padilla, Juan Bravo, and Francisco Maldonado. They were beheaded the next morning in the Plaza of Villalar. Many royalist nobles were there to watch. The remaining rebel army at Villalar broke apart. Some tried to join Acuña's army near Toledo, and others simply deserted. The rebellion had suffered a terrible blow.

End of the War

After the Battle of Villalar, the towns of northern Castile quickly surrendered to the king's troops. All its cities returned their loyalty to the king by early May. Only Madrid and Toledo kept their Comunidades alive.

Toledo's Last Stand

The first news of Villalar reached Toledo on April 26. But the local Comunidad mostly ignored it. The true scale of the defeat became clear in a few days. Survivors started arriving in the city and confirmed that the three rebel leaders had been executed. Toledo declared a period of mourning for Juan de Padilla.

After Padilla's death, Bishop Acuña lost popularity. María Pacheco, Padilla's widow, gained influence. People began to suggest negotiating with the royalists to avoid more suffering in the city. The situation looked even worse after Madrid surrendered on May 11. It seemed only a matter of time before Toledo fell.

However, there was still some hope for the rebels. Castile had moved some of its troops from occupied Navarre to fight the Comuneros. King Francis I of France used this chance to invade Navarre with support from the Navarrese. The royalist army had to march to Navarre to respond, instead of attacking Toledo. Acuña left Toledo to go to Navarre, but he was recognized and caught. It's debated whether he was trying to join the French and keep fighting, or just fleeing.

María Pacheco took control of Toledo and the remaining rebel army. She lived in the Alcázar, collected taxes, and strengthened defenses. She asked her uncle, the respected Marquis of Villena, to talk with the Royal Council. She hoped he could get better terms for surrender. The Marquis eventually stopped the talks. María Pacheco then negotiated directly with Prior Zúñiga, the commander of the royalist forces surrounding the city. Her demands were small, like protecting her children's property and reputation.

Still worried about the French, the royal government agreed. With everyone's support, Toledo surrendered on October 25, 1521. On October 31, the Comuneros left the Alcázar of Toledo, and new officials were appointed to run the city. The agreement promised freedom and property to all Comuneros.

Revolt of February 1522

The new administrator of Toledo brought the city back under royal control. But he also angered former Comuneros. María Pacheco remained in the city and refused to hand over all hidden weapons. She wanted Charles V to personally sign the agreements made with the Order of St. John. This unstable situation ended on February 3, 1522, when the generous surrender terms were canceled. Royal soldiers filled the city, and the administrator ordered Pacheco's execution. Riots broke out in protest. The situation was temporarily fixed thanks to María de Mendoza, María Pacheco's sister. Another truce was granted. While the former Comuneros were defeated, María Pacheco used the distraction to escape to Portugal, dressed as a farmer.

Pardon of 1522

Charles V returned to Spain on July 16, 1522. There were some punishments and revenge against former Comuneros, but only now and then. Many important people had supported the Comuneros, or were slow to declare loyalty to the king. Charles thought it was unwise to push the issue too much.

Back in Valladolid, Charles announced a general pardon on November 1. This pardon gave forgiveness to almost everyone involved in the revolt. Only 293 Comuneros were excluded, a small number given how many rebels there were. Both Pacheco and Bishop Acuña were among the 293 not pardoned. More pardons were given later, after pressure from the Cortes. By 1527, the punishments had completely stopped. Of the 293, 23 were executed, 20 died in prison, 50 bought their freedom, and 100 were pardoned later. What happened to the rest is unknown.

What Happened After

María Pacheco successfully escaped to Portugal. She lived there for the remaining ten years of her life. Bishop Acuña, captured in Navarre, lost his church position and was executed after he killed a guard while trying to escape. Pedro Girón received a pardon. But he had to go live in Oran in North Africa, where he served as a commander against the Moors. Queen Joanna remained locked up in Tordesillas by her son for 35 more years, until she died.

Emperor Charles V went on to rule one of the largest empires in European history. Because of this, Charles was almost always at war. He fought France, England, the Pope's lands, the Ottoman Turks, the Aztecs, the Incas, and the Protestant Schmalkaldic League. Spain provided most of the armies and money for his empire during this time. Charles put Castilians in high government jobs in both Castile and the wider Empire. He generally left Castile's government in Castilian hands. In this way, the revolt could be seen as successful.

Some of the changes made by Isabella I, which reduced noble power, were reversed. This was the price for getting the nobles to support the king. However, Charles understood that nobles gaining too much power had helped cause the revolt. So, he started a new reform program. Unpopular, corrupt, and ineffective officials were replaced. The Royal Council's power to judge cases was limited, and local courts were made stronger. Charles also changed who was on the Royal Council. Its hated president was replaced, the nobles' role was reduced, and more common gentry were added. Charles realized that city leaders needed to feel they had a part in the royal government again. So, he gave many of them positions, special rights, and government salaries. The Cortes, while not as powerful as the Comuneros hoped, still kept its power. It was still needed to approve new taxes and could advise the king. Charles also told his officials not to use overly harsh methods. He saw how his tough treatment of the Cortes of Corunna had backfired.

Later Impact

The revolt was still fresh in Spain's memory. It is mentioned in several books during Spain's Golden Age. Don Quixote talks about the rebellion, and Francisco de Quevedo uses "comunero" to mean "rebel."

In the 1700s, the Comuneros were not seen in a good light by the Spanish Empire. The government did not want to encourage rebellions. They only used the term to criticize those who opposed them. In the Revolt of the Comuneros in Paraguay, the rebels didn't choose the name themselves. It was used to insult them as traitors. Another Revolt of the Comuneros in New Granada (now Colombia) was also unrelated to the original, except in name.

In the early 1800s, scholars like Manuel Quintana started to see the Comuneros in a better way. They saw them as early fighters for freedom against absolute rule. The loss of Castilian liberty was linked to Spain's later decline. The first big event to remember them happened in 1821, 300 years after the Battle of Villalar. Juan Martín Díez, a nationalistic military leader who fought against Napoleon, led a trip to find and dig up the remains of the three leaders executed in 1521. Díez praised the Comuneros on behalf of the liberal government at the time. This was likely the first time the government officially recognized their cause positively.

This view was challenged by conservatives. They saw a strong, central government as modern and good. Especially after the chaos of the 1868 Revolution in Spain. Manuel Danvila, a conservative government minister, published a six-volume history of the Comunidades from 1897 to 1900. This was an important work about the revolt. Using original documents, Danvila focused on the Comuneros' tax demands. He described them as old-fashioned, against progress, medieval, and feudal. Even a liberal thinker, Gregorio Marañón, shared a negative view of the Comuneros. He saw the conflict as a fight between a modern, open state and a conservative, fearful Spain that was too sensitive about religion and culture.

General Franco's government (1939-1975) also encouraged a negative view of the Comuneros. According to approved historians, the revolt was just about small Spanish regionalism. Franco tried hard to discourage such ideas. Also, the Comuneros supposedly didn't appreciate Spain's "imperial destiny."

Since the mid-1900s, others have looked for more economic reasons for the revolt. Historians like José Antonio Maravall and Joseph Pérez describe the revolt as different social groups forming alliances based on changing economic interests. They saw city workers and artisans joining with intellectuals and lower nobles against the aristocrats and merchants. Maravall, who sees the revolt as one of the first modern revolutions, especially highlights the ideas and intellectual nature of the revolt. For example, it included the first proposed written constitution for Castile.

With Spain's return to democracy after Franco's death, celebrating the Comuneros became allowed again. On April 23, 1976, a small secret ceremony was held in Villalar. Just two years later, in 1978, the event became a huge demonstration of 200,000 people supporting Castilian self-rule. The autonomous community of Castile and León was created in 1983 because of public demand. It recognized April 23 as an official holiday in 1986. Similarly, since 1988, the Castilian nationalist party Tierra Comunera celebrates February 3 in Toledo. This celebration honors Juan López de Padilla and María Pacheco. It remembers the rebellion in 1522, the last event of the war.

|

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de las Comunidades de Castilla para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de las Comunidades de Castilla para niños

- Italian War of 1521–1526

- List of people associated with the Revolt of the Comuneros

- Military history of the Revolt of the Comuneros

- Revolt of the Brotherhoods

- Spanish conquest of Iberian Navarre