Ottoman–Habsburg wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ottoman–Habsburg wars |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman wars in Europe | |||||||

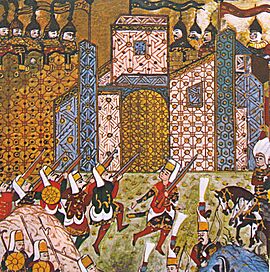

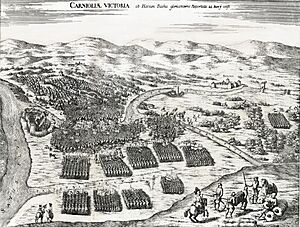

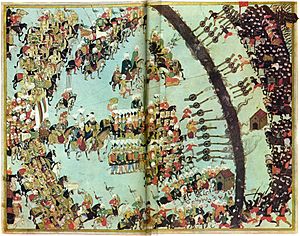

Left to right from the top: the Siege of Vienna, the Siege of Szigetvár, the Long Turkish War, the Battle of Saint Gotthard, the Battle of Vienna, the Siege of Belgrade |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Vassal states:

Allies:

|

Non-Habsburg states of the Holy Roman Empire:

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Mediterranean: 900,000–1,000,000 deaths (1470–1574) | |||||||

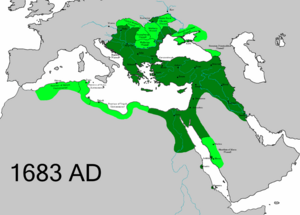

The Ottoman–Habsburg wars were a series of major conflicts. They were fought from the 16th to the 18th centuries. The main groups involved were the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy. Sometimes, other groups like the Kingdom of Hungary and Habsburg Spain helped the Habsburgs. Most of these wars happened on land in places like Hungary, Transylvania (now in Romania), Vojvodina (now in Serbia), Croatia, and central Serbia.

By the 1500s, the Ottomans were a big threat to European countries. Their ships took over areas in the Aegean and Ionian seas. Also, pirates supported by the Ottomans attacked Spanish lands in North Africa. At the same time, European powers were busy with their own problems. The Protestant Reformation caused religious conflicts. There was also a big rivalry between France and the Habsburgs. These issues made it harder for Christian countries to unite against the Ottomans.

The Ottomans made big gains early on. They won a major battle at Mohács in 1526. This victory turned about one-third of central Hungary into a land that had to pay tribute to the Ottomans. After the Siege of Vienna in 1683, the Habsburgs formed a large group of European powers called the Holy League. They fought the Ottomans to take back Hungary. The Great Turkish War ended with the Holy League winning a big victory at Zenta.

The wars finally ended after Austria joined a war with Russia from 1787 to 1791. Even after that, there was still tension between Austria and the Ottoman Empire. But they never fought another war directly. In fact, they became allies in World War I. After that war, both empires broke apart.

Historians used to focus on the second Siege of Vienna in 1683. They saw it as a key Austrian victory that saved Western culture. It was also seen as the start of the Ottoman Empire's decline. More recent historians look at the bigger picture. They note that the Habsburgs were also dealing with internal rebellions. They were also fighting Prussia and France for control of central Europe.

A big advantage for the Europeans was their improved military tactics. They learned to combine infantry, artillery, and cavalry effectively. However, the Ottomans were still strong. They kept up with the Habsburgs militarily until the mid-1700s. Historian Gunther E. Rothenberg pointed out that the Habsburgs also built special military communities. These communities protected their borders and provided many well-trained soldiers.

Contents

The Start of the Conflicts

The Habsburgs were sometimes kings of Hungary and emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. But the wars between Hungary and the Ottomans involved other ruling families too. People in Western Europe saw the strong Ottoman Empire as a threat to Christianity. They offered support to stop the Ottoman advance into Central Europe and the Balkans. Two major attempts were the Crusades of Nicopolis (1396) and Varna (1443–44).

For a while, the Ottomans were busy fighting rebels in the Balkans, like Vlad Dracula. But once these rebels were defeated, Central Europe was open to Ottoman invasion. The Kingdom of Hungary now shared a border with the Ottoman Empire and its smaller states.

After King Louis II of Hungary died at the Battle of Mohács in 1526, his wife, Queen Mary of Austria, went to her brother, Ferdinand I. Ferdinand's claim to the Hungarian throne became stronger when he married Anne. She was King Louis II's sister and the only other family member who could claim the throne.

So, Ferdinand I was chosen as King of Bohemia. Then, at a meeting in Pozsony, he and his wife were elected king and queen of Hungary. This went against the Ottoman goal of putting John Zápolya on the Hungarian throne. This disagreement set the stage for the long conflict between the two powerful empires.

Key Conflicts and Battles

| Name | Date | Result |

|---|---|---|

|

Suleiman I's campaign of 1529 |

1529 | Ottoman victory |

| 1529 | Austrian victory | |

|

Ottoman-Habsburg War (1526–1538) |

1526–1538 | Ottoman victory |

| 1535 | Spanish victory | |

| Ottoman-Habsburg War (1540–1547) | 1540–1547 | Ottoman victory |

| 1541 | Ottoman-Algerian victory | |

| Ottoman-Habsburg War (1551–1562) | 1551–1562 | Ottoman victory |

| 1558 | Ottoman-Algerian victory | |

| 1563 | Spanish victory | |

| Ottoman-Habsburg War (1565–1568) | 1565–1568 | Ottoman victory |

| 1593–1606 | Inconclusive | |

|

Austro-Turkish War (1663–1664) |

1663–1664 | Inconclusive |

| 1683–1699 | Austrian victory | |

| 1716–1718 | Austrian victory | |

| 1737–1739 | Ottoman victory | |

|

Austro-Turkish War (1788–1791) |

1788–1791 | Inconclusive, end of Austro-Ottoman Wars |

Habsburg Efforts and Challenges

The Austrian lands were in a tough financial spot. So, Ferdinand introduced a "Turkish Tax" to raise money. But even with this tax, he couldn't collect enough to pay for defense. His yearly income only allowed him to hire 5,000 soldiers for two months. Ferdinand had to ask his brother, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, for help. He also borrowed money from rich bankers like the Fugger family.

In 1527, Ferdinand I attacked Hungary. Hungary was weak due to internal conflicts. Ferdinand wanted to remove John Zápolya and take control. John couldn't stop Ferdinand's army, which captured Buda and other important towns. The Ottoman sultan was slow to react. He only sent a large army of about 120,000 men in May 1529 to help his ally. The Austrian Habsburgs needed Hungary's economic power for the wars against the Ottomans.

During these wars, the Kingdom of Hungary shrank by about 70%. Despite losing land and people, the smaller, war-torn Royal Hungary remained very important. It was Ferdinand's biggest source of money by the end of the 1500s.

Military Technology

Early Turkish hand cannons were called "Şakaloz." This word came from the Hungarian hand cannon "Szakállas puska" from the 1400s.

Even though Ottoman Janissaries started using firearms in battles in the early 1500s, their use of handheld guns spread slowly. Much slower than in Western Christian armies. For example, Wheellock firearms were new to Ottoman soldiers until the siege of Székesfehérvár in 1543. Christian armies in Hungary and Western Europe had been using them for decades. A report from 1594 said that Ottoman soldiers still hadn't started using pistols.

In 1602, the grand vizier (a high-ranking Ottoman official) reported from Hungary. He said that Christian forces had better firepower. He wrote that "in a field or during a siege we are in distressed position, because the greater part of the enemy forces are infantry armed with muskets, while the majority of our forces are horsemen, and we have very few specialists skilled in the musket."

Another report from 1637 by a Venetian ambassador in Constantinople said that "few Janissaries even knew how to use an arquebus" (a type of early rifle). This shows that the Ottomans were behind in firearm technology compared to their European enemies.

Siege of Vienna (1529)

Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent easily took back most of the lands Ferdinand had gained. To Ferdinand I's disappointment, only the fortress of Pozsony held out. Given the size of Suleiman's army and the damage done to Hungary, many towns didn't want to fight.

The Sultan arrived at Vienna on September 27, 1529. Ferdinand's army had about 16,000 soldiers. He was outnumbered roughly 7 to 1. Vienna's walls were thick, but the Ottomans had heavy cannons. However, these cannons got stuck in mud due to heavy rain and had to be left behind.

Ferdinand defended Vienna with great effort. By October 12, after much digging and counter-digging, the Ottomans decided to give up the siege. On October 14, they left. The Ottoman army's retreat was made harder by Pozsony, which attacked their forces. Early snowfall made things even worse. It would be three more years before Suleiman could campaign in Hungary again.

The Little War (1526–1568)

After the defeat at Vienna, the Ottoman Sultan focused on other parts of his empire. Archduke Ferdinand used this chance to attack in 1530. He recaptured Esztergom and other forts. An attack on Buda was stopped only because Ottoman soldiers were there.

Just like before, when the Ottomans returned, the Habsburgs in Austria had to defend themselves. In 1532, Suleiman sent a huge Ottoman army to take Vienna. But the army took a different route to Kőszeg. A small force of only 700 led by the Croatian earl Nikola Jurišić defended the fortress of Güns. The defenders agreed to an "honorable" surrender for their safety. The Sultan then left, happy with his success. He recognized Austria's small gains in Hungary. But he forced Ferdinand to accept John Zápolya as King of Hungary. Tatar raiders plundered Lower Austria and took many people as slaves.

The peace between Austria and the Ottomans lasted nine years. But John Zápolya and Ferdinand kept fighting small battles along their borders. In 1537, Ferdinand broke the peace treaty. He sent his best generals to attack Osijek, which was another Ottoman victory. Still, Ferdinand was recognized as the heir to the Kingdom of Hungary by the Treaty of Nagyvárad.

After John Zápolya died in 1540, Ferdinand's claim to the throne was ignored. Instead, it went to John's son, John Sigismund Zápolya. The Austrians tried to enforce the treaty by advancing on Buda. But they were defeated again by Suleiman. The old Austrian General Wilhelm von Roggendorf was not effective. Suleiman then defeated the remaining Austrian troops and took control of Hungary. By the time a peace treaty was signed in 1551, Habsburg Hungary was mostly just border land.

In 1552, two Ottoman armies crossed into Hungary. One army, led by Hadim Ali Pasha, attacked the western and central parts of the country. The second army, led by Kara Ahmed Pasha, attacked forts in the Banat region. Ottoman troops captured most of the castles in the Hont and Nógrád counties. The Habsburg army, led by Erasmus von Teufel, tried to stop the Ottomans at Plášťovce. But they were completely defeated in a two-day battle. About 4,000 German and Italian prisoners were sent to Constantinople.

The two Ottoman armies joined near Szolnok. They then besieged and captured Szolnok Castle. After that, they moved towards Eger, a gateway to Upper Hungary. By the end of July, there was a huge gap in Hungary's border defense system.

In September 1552, Kara Ahmed Pasha's Ottoman forces besieged Eger Castle in northern Hungary. But the defenders, led by István Dobó, fought back and defended the castle. The siege of Eger (1552) became a symbol of national defense and heroism in Hungary.

In 1554, the town of Fiľakovo in south-central Slovakia was captured by the Turks. It became the center of a Turkish district until 1593. Then, Imperial troops recaptured it. On March 27, 1562, Hasszán, the leader of Fiľakovo castle, defeated the Hungarian army. This battle happened near Sečany.

After the Turks captured Buda in 1541, western and northern Hungary recognized a Habsburg as king. This was called "Royal Hungary". The central and southern areas were controlled by the Sultan, called "Ottoman Hungary". The eastern part became the Principality of Transylvania. Most of the Ottoman soldiers in Hungary were Orthodox and Muslim Balkan Slavs, not ethnic Turks. Southern Slavs also acted as light troops, raiding Hungarian territory.

Both sides missed chances in the Little War. Austrian attempts to gain more power in Hungary failed. Ottoman efforts to reach Vienna also failed. Still, everyone knew the Ottoman Empire was a very powerful and dangerous threat. Even so, the Austrians kept attacking. Their generals became known for causing many deaths. Costly battles like those at Buda and Osijek were sometimes avoided, but not always.

Habsburg interests were divided. They were fighting for war-torn European land under Ottoman control. They were also trying to stop the Holy Roman Empire from breaking apart. Plus, they supported Spain's goals in North Africa, the Low Countries, and against the French.

The Ottomans, while still very strong, couldn't expand as much as they had before. In the east, they faced more wars against their Shi'ite enemies, the Safavids. Both the French (since 1536) and the Dutch (since 1612) sometimes worked with the Ottomans against the Habsburgs.

Suleiman the Magnificent led one last campaign in 1566. It ended at the siege of Szigetvár. The siege was supposed to be a quick stop before taking Vienna. But the fortress held out against the Sultan's armies. The Sultan, who was 72 years old, died during the siege. His doctor was killed to keep the news from the troops. The Ottomans, not knowing their leader had died, took the fort. The campaign ended soon after, without moving on Vienna.

Peace was finally agreed upon in Adrianople in 1568. It was renewed in 1576, 1584, and 1591. War didn't break out again between the Habsburgs and Ottomans until 1593, in the Long Turkish War. However, during this peaceful time, small-scale fighting continued. This was known as the "Little War." In 1571, the Turks destroyed the Hodejov castle. In 1575, they captured the Modrý Kameň castle. In 1588, there was a battle near Szikszó, where the Hungarian army defeated the Turks.

War in the Mediterranean Sea

The Ottoman Empire quickly became a strong naval power. In the 1300s, they had a small navy. By the 1400s, they had hundreds of ships. They attacked Constantinople and challenged the navies of Venice and Genoa. In 1480, the Ottomans tried but failed to capture Rhodes, a stronghold of the Knights of St. John. When they returned in 1522, they succeeded. The Christian powers lost a key naval base.

In response, Charles V led a huge Holy League army of 60,000 soldiers. They attacked the Ottoman city of Tunis in 1535. After Hayreddin Barbarossa's fleet was defeated, Charles's army killed 30,000 of the city's people. Then, the Spanish put a friendly Muslim leader in charge. But the campaign wasn't a complete success. Many Holy League soldiers got sick and died. Also, much of Barbarossa's fleet wasn't in North Africa. The Ottomans won a victory against the Holy League in 1538 at the Battle of Preveza in western Greece.

In 1541, Charles led a sea and land attack on the Ottoman stronghold of Algiers. It was defended by Hasan Agha. As Charles landed, his fleet was hit by a storm. Many ships were lost. Charles's land force marched towards Algiers. But attacks by Janissaries stopped their advance, and Charles pulled back.

The Great Siege of Malta

Even though Rhodes was lost, Cyprus (an island farther from Europe) remained Venetian. When the Knights of St. John moved to Malta, the Ottomans realized their victory at Rhodes only moved the problem. Ottoman ships were often attacked by the Knights. The Knights tried to stop Ottoman expansion to the West. Ottoman ships also attacked many parts of southern Europe and Italy. This was part of their larger war, allied with France against the Habsburgs.

The situation became critical in 1565. Suleiman, who had won at Rhodes in 1522, decided to destroy the Knights' base at Malta. The presence of the Ottoman fleet so close to the Pope worried the Spanish. They started gathering a small force to help the siege. Then they gathered a larger fleet to rescue the island. The modern, star-shaped St Elmo was captured, but with heavy losses. These losses included the Ottoman general Turgut Reis. The rest of the island was too difficult to take. Even after this, Barbary pirates continued their raids. The victory at Malta didn't really affect Ottoman military strength in the Mediterranean.

Cyprus and Lepanto

Suleiman the Magnificent died in 1566. His son, Selim II, took power. Selim, sometimes called "Selim the Sot," put together a huge force to take Cyprus from Venice. Selim chose not to help a rebellion by Moors that the Spanish crown had started to put down. If Selim had landed in Spain, he might have been cut off. This is because after he captured Cyprus in 1571, he suffered a huge naval defeat at the Battle of Lepanto.

The Holy League, formed by the Pope to defend Cyprus, arrived too late to save the island. Even though Famagusta resisted for 11 months, it fell. But the Holy League had gathered much of Europe's military strength. They had more ammunition and armor. They dealt a big blow to the Ottomans. The chance to retake Cyprus was lost due to arguments after the victory. So, when the Venetians signed a peace treaty with the Ottomans in 1573, they had to agree to Ottoman terms.

The Long Turkish War (1593–1606)

After Suleiman died in 1566, Selim II was less of a threat to Europe. Although Cyprus was finally captured, the Ottomans failed against the Habsburgs at sea. Selim died soon after. His son, Murad III, took power. Murad was more interested in his Harem than in war. With things getting worse, the Empire found itself at war with the Austrians again.

Early in the war, the Ottomans' military situation got worse. The regions of Wallachia, Moldova, and Transylvania got new rulers. These rulers stopped being loyal to the Ottomans. At the Battle of Sisak, a group of Ottoman raiders were completely defeated. They were fighting tough Imperial troops from the Low Countries. In response, the Grand Vizier sent a large army of 13,000 Janissaries and many European soldiers. But the Janissaries rebelled against fighting in winter. The Ottomans captured little more than Veszprém.

Technological problems also made the Ottoman position in Hungary much worse.

In 1594, Grand Vizier Sinan Pasha gathered an even larger army. Facing this threat, the Austrians stopped their attack on Gran. Gran was a fortress that had fallen during Suleiman's time. Then, the Austrians lost Raab. For the Austrians, the only good news that year was that the fortress of Komárno held out. It lasted long enough against the Vizier's forces for them to retreat for the winter.

Despite their success the previous year, the Ottomans' situation worsened in 1595. A Christian alliance of former Ottoman vassal states and Austrian troops recaptured Esztergom. They marched south along the Danube River. Michael the Brave, the prince of Wallachia, started a campaign against the Turks (1594–1595). He captured several castles near the Lower Danube, including Giurgiu, Brăila, Hârşova, and Silistra. His Moldavian allies defeated the Turks in Iaşi and other parts of Moldavia. Michael continued his attacks deep into the Ottoman Empire. He took the forts of Nicopolis, Ribnic, and Chilia. He even reached Adrianople (Edirne), the former Ottoman capital. No Christian army had been in that region since the Byzantine Empire.

After the Ottoman army was defeated in Wallachia (at the Battle of Călugăreni), and after several failed fights with the Habsburgs, the new Sultan Mehmed III was alarmed. He killed his 19 brothers to take power. He then personally led his army to northwestern Hungary to fight his enemies. In 1596, Eger fell to the Ottomans. At the important Battle of Keresztes, a slow Austrian response led to their defeat by the Ottomans. Mehmet III's lack of experience showed when he didn't reward the Janissaries for their efforts. Instead, he punished them, which caused a rebellion.

The Austrians restarted the war in the summer of 1597. They pushed southward, taking Pápa, Tata, Raab (Győr), and Veszprém. More Habsburg victories happened when a Turkish relief force was defeated at Grosswardein (Nagyvárad). The Turks were angered by these defeats and fought back harder. By 1605, after many failed Austrian attempts to help and failed sieges by both sides, only Raab remained in Austrian hands. That year, a pro-Turkish prince was chosen as the leader of Transylvania by Hungarian nobles. The war ended with the Peace of Zsitva-Torok.

The Great Turkish War (1683–1699)

In August 1652, Ádám Forgách organized the defense against Ottoman raiders. He faced them near Veľké Vozokany in Upper Hungary (now Slovakia). He defeated the Turkish troops in the two-day Battle of Vezekény.

In 1663, the Ottomans launched an invasion of the Habsburg Monarchy. They captured the fortress of Nové Zámky. They crossed the Váh river and invaded Moravia. The war ended at the Battle of St. Gotthard. The Christians won this battle, mainly thanks to an attack by 6,000 French troops. They were led by François d'Aubusson de La Feuillade and Jean de Coligny-Saligny.

The Austrians couldn't follow up on this victory. This was because Louis XIV of France intervened on the Rhine. In such a situation, the Protestant allies of the Catholic Habsburgs would not have been reliable. They wanted Austria and themselves to fight the French in a German alliance. So, the Ottomans turned their attention north again, against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. By now, this kingdom was in a terrible state. Its parliament was divided, and its treasury was empty. Still, John III Sobieski, king of Poland, led a decisive victory against the Ottomans at the Second Battle of Khotyn.

The Ottomans were restless and got another chance in 1682. The Grand Vizier led a huge army into Hungary and towards Vienna. This was in response to Habsburg raids into Ottoman-controlled Hungary.

The Siege of Vienna (1683)

In 1683, after 15 months of gathering forces, the Grand Vizier reached Vienna. He found the city well defended and prepared. What was worse for the Vizier were the many alliances the Austrians had made, including with Sobieski. When the siege of Vienna began in 1683, Sobieski and his alliance of Germans and Poles arrived. They came just as Vienna's defenses were about to break. In one of history's truly decisive battles, the Ottomans were defeated and the siege was lifted. This battle marked the highest point of Ottoman expansion.

Taking Back Hungarian Lands

In 1686, two years after an unsuccessful siege of Buda, a new European campaign began. The goal was to enter Buda, the old capital of medieval Hungary. This time, the Holy League's army was twice as large, with over 74,000 men. It included soldiers from Germany, Croatia, the Netherlands, Hungary, England, Spain, Czech lands, Italy, France, Burgundy, Denmark, and Sweden. Other Europeans joined as volunteers, artillerymen, and officers. The Christian forces recaptured Buda.

In 1687, the Ottomans raised new armies and marched north again. However, Charles V, Duke of Lorraine stopped the Turks at the Second Battle of Mohács. This avenged the loss from over 160 years ago by Suleiman the Magnificent. The Ottomans kept fighting the Austrians who were pushing south. They didn't want to negotiate from a weak position. Only when the Ottomans suffered another terrible defeat at the Battle of Zenta in 1697 did they ask for peace. The resulting Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 gave territories, the rest of Hungary, and control of Transylvania to the Austrians.

Across Europe, Protestants and Catholics praised Prince Eugene of Savoy. They called him "the savior of Christendom." English volunteers, including a son of Prince Rupert of the Rhine (nephew of Charles I of England), and Protestants from as far as Scotland fought in the Prince's army. For the Ottomans, the years between 1683 and 1702 were sad. Twelve Grand Viziers were removed from power in 19 years. This showed the decline of what was once the most powerful position in one of the world's strongest empires.

-

Ottoman Sipahis at the Battle of Vienna in 1683.

The Final Stages of the Wars

18th Century Conflicts

The Great Turkish War was a disaster for the Ottomans. But the Habsburgs soon got involved in another destructive European war. This was the War of the Spanish Succession against their old rivals, the French.

The Ottomans were feeling confident after winning against the Russians in 1711 and the Venetians in 1715. So, they declared war on the Habsburg monarchy in 1716. They marched north from Belgrade in July, led by Grand Vizier Ali Pasha. However, the invasion was a catastrophe. The Ottoman army was crushed, and the Grand Vizier was killed at the Battle of Petrovaradin in August. This was done by a smaller Austrian army led by Prince Eugene of Savoy. Prince Eugene went on to capture Belgrade a year later.

At the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718, the Austrians gained control of the Banat of Temeswar, Serbia, and Oltenia.

Austria joined Russia in a war against the Ottomans in 1737. At the Battle of Grocka in 1739, the Austrians were defeated by the Ottomans. As a result, with the Treaty of Belgrade (1739), the lands gained in Serbia and Wallachia were lost. The Habsburgs gave Serbia (including Belgrade), the southern part of the Banat of Temeswar, and northern Bosnia back to the Ottomans. They also gave the Banat of Craiova (Oltenia) to Wallachia (an Ottoman subject). The new border was set at the Sava and Danube rivers.

The Austro-Turkish War (1788–91) was not a clear victory for either side. Austrian land gains were small in the Treaty of Sistova. The Austrians had taken large areas like Bosnia, Belgrade, and Bucharest. But they were threatened by the upcoming French Revolutionary Wars and tensions with Prussia. Prussia was threatening to get involved. The gains from this war were the town of Orșova in Wallachia and two small towns on the Croatian border. This conflict was the last time the two powers fought directly. However, political and military tensions continued.

The 19th Century and Beyond

For the next 100 years, both the Austrians and the Ottomans slowly lost power. Other European countries like France, Britain, Prussia, and Russia became stronger. Neither the Ottomans nor the Austrians had the strong industries that their European neighbors did. But the Ottomans were even further behind than the Austrians. So, Ottoman power declined faster.

In the Balkans, growing feelings of nationalism (people wanting their own independent nations) became a bigger problem. The Ottomans, who were less skilled militarily, struggled with this. After 1867, the Austrians made a deal with the Hungarians. They formed Austria-Hungary. This stopped a major ethnic group from rebelling in the short term. The Ottomans couldn't achieve the same benefits.

Efforts to catch up with European technology led Ottoman officers and thinkers to study abroad. But this plan backfired. These individuals brought back European ideas of Enlightenment and egalitarianism (equality). These ideas clashed with the traditional Ottoman system, which was ruled by Turks and had a strict social structure. Because of this, Ottoman power collapsed more quickly. They were powerless to stop Bosnia from being occupied in 1878 (and officially taken over in 1908).

Austria and other major powers (Britain, Prussia, Russia) saved the Ottoman ruling family from an early collapse. This happened when Egypt rebelled against the Ottomans in 1840. British, Austrian, and Ottoman ships attacked ports in Syria and Alexandria. The allies took Acre. This forced Egypt to give up its attempt to take control of the Middle East from the Ottomans.

World War I

Relations between Austria and the Ottomans began to get better. They saw a common threat in Russia. They also saw a common ally in Germany to counter Russia. The Ottomans hoped the Germans would help them industrialize their nation. This would help them defend against the Russians. Russia had become very determined to push the Turks out of Crimea and the Caucasus.

Meanwhile, the German Empire appealed to the Austrians because of their shared culture and language. Germany also offered fair terms after the Austro-Prussian War. The Austrians didn't want to see Russia expand towards their borders at the Ottomans' expense. So, in the years before World War I, these two former enemies became allies. They fought against France, Russia, and Britain. In 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Empire surrendered and was divided by treaties. The Ottomans also faced a similar fate.

See also

- Ottoman wars in Europe

- Ottoman Navy

- List of Ottoman conquests, sieges and landings

- Ottoman decline thesis

- Croatian–Ottoman wars

- Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe

- Barbary slave trade