Cossack Hetmanate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Zaporizhian Host

Військо Запорозьке (Ukrainian)

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1648–1764 | |||||||||||||||

The Zaporizhian Cossack Host in 1654

|

|||||||||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Ottoman Empire (1655–1657) (1669–1685) Protectorate of the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire (since 1654) Concurrent with the Kiev Governorate (1708–1764) |

||||||||||||||

| Capital | Chyhyryna (1648–1676) Baturynb (1663–1708) Hlukhivc (1708–1764) |

||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Ruthenian (Old Ukrainian), Russian, Polish, Romanian | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Stratocratic Cossack Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Hetman | |||||||||||||||

|

• 1648–1657 (first)

|

Bohdan Khmelnytsky | ||||||||||||||

|

• 1750–1764 (last)

|

Kirill Razumovsky | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | General Cossack Council Council of Officers |

||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Zboriv

|

18 (8) August 1648 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Bila Tserkva

|

1651 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Pereyaslav

|

1654 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Andrusovo

|

1667 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Hetman post abolished in Poland

|

1686 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Kolomak Articles

|

1687 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Hetman post abolished in Russia

|

21 (10) November 1764 | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Ukraine Russia Moldova Belarus |

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

The Cossack Hetmanate (Ukrainian: Гетьманщина, romanized: Hetmanshchyna), also known as the Zaporizhian Host, was a special Cossack state in central Ukraine. It existed from 1648 to 1764. Its system of government lasted a bit longer, until 1782.

This state was started by Bohdan Khmelnytsky, a famous Cossack leader. He led an uprising against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1648 to 1657. In 1654, the Hetmanate formed an alliance with the Tsardom of Russia through the Pereiaslav Agreement. This agreement is a very important event in Ukrainian and Russian history.

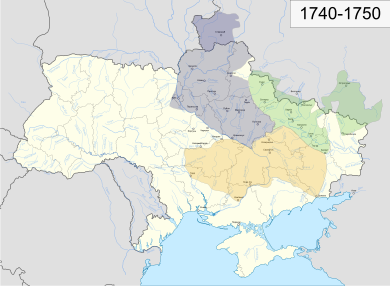

Later, in 1667, the Treaty of Andrusovo was signed. This treaty divided the Hetmanate into two parts along the Dnieper River. One part stayed with Poland, and the other became part of Russia.

After a leader named Ivan Mazepa tried to break away from Russia in 1708, the Hetmanate's freedom was greatly limited. Finally, in 1764, Catherine II of Russia officially ended the Hetmanate's self-rule. Its lands became part of the Russian Empire.

Contents

What Was the Cossack Hetmanate Called?

The official name of this state was the Zaporizhian Host or Army of Zaporizhia. The name "Hetmanate" (Ukrainian: Гетьманщина) became popular later, in the late 1800s. It comes from the word hetman, which was the title for the leader of the Zaporizhian Army.

Even though it wasn't always centered in Zaporizhia, the name "Zaporizhian" was used because it came from the Ukrainian Cossacks who lived "beyond the rapids" of the Dnieper River.

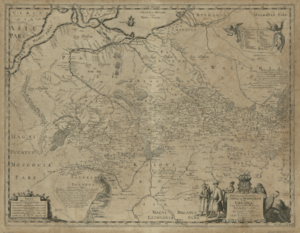

Some old documents and maps called the Hetmanate "Ukraine" or "the Land of Cossacks." The Ottoman Empire called it the "Country of Ukraine." In Russian letters, it was often called "Little Russia."

How the Hetmanate Began and Grew

Starting the Cossack State

The Khmelnytsky Uprising was a big rebellion led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky. After many successful battles against the Poles, Khmelnytsky entered Kyiv triumphantly in December 1648. People saw him as a hero who freed them from Polish rule.

In February 1649, Khmelnytsky told Polish leaders he wanted to be the Hetman of a large Ruthenian state. He planned to continue fighting if his demands were not met. The Polish king sent troops, but they had to retreat to Zbarazh because the Cossack forces were too strong.

Khmelnytsky besieged Zbarazh. When the Polish king tried to help, Khmelnytsky and his allies, the Tatars, ambushed him near Zboriv. This led to peace talks, and the Treaty of Zboriv was signed in August 1649.

As the leader of the Hetmanate, Khmelnytsky worked to build a new state. He set up a military, government, and financial system. He united Ukrainian society under his rule, creating a new elite from Cossack officers and local nobles.

The Hetmanate used Polish money and Polish was an official language at first. But after 1667, the common Ukrainian language (prosta mova) became widely used in official documents.

Becoming a Russian Protectorate

After the Crimean Tatars betrayed the Cossacks in 1653, Khmelnytsky realized he couldn't rely on the Ottoman Empire for help against Poland. He decided to ask the Tsardom of Russia for support.

In January 1654, Khmelnytsky and other Cossack leaders met with the Tsar's ambassador in Pereiaslav. A treaty was signed in April in Moscow. This treaty made the Zaporozhian Host an independent Hetmanate under Russian protection. This agreement also led to the Russo-Polish War.

The Ruin: A Time of Trouble

The period from 1657 to 1687 is known as "the Ruin". It was a time of many civil wars and instability in the Hetmanate. After Bohdan Khmelnytsky died in 1657, his young and inexperienced son, Yurii Khmelnytsky, became the next Hetman.

However, Ivan Vyhovsky, a trusted adviser to Bohdan Khmelnytsky, was also elected Hetman. This caused disagreements among the Cossacks. Russia also seemed to support different groups, making the situation worse.

Vyhovsky tried to make peace with Poland by signing the Treaty of Hadiach in 1658. This treaty would have made Ukraine an equal part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. But many Cossacks did not like this idea, and more rebellions broke out. Vyhovsky eventually left his position.

In 1667, the Russo-Polish War ended with the Treaty of Andrusovo. This treaty officially split the Cossack Hetmanate along the Dnieper River. Left-bank Ukraine became part of Russia, while Right-bank Ukraine remained with Poland. For a while, Petro Doroshenko tried to unite both banks and even allied with the Ottomans. However, by 1690, Poland regained control of Right-bank Ukraine.

The Time of Ivan Mazepa

The period of "the Ruin" ended when Ivan Mazepa became Hetman in 1687. He ruled until 1708 and brought stability back to the Hetmanate. Under his leadership, the Hetmanate thrived, especially in art and building. A unique style called Cossack Baroque architecture developed during his time.

During Mazepa's rule, the Great Northern War started between Russia and Sweden. Mazepa first allied with Peter I of Russia. But he became unhappy with Russia's growing control over the Hetmanate.

In 1708, Mazepa and some Cossacks allied with the Swedes, hoping to gain full independence for Ukraine. However, Russia won the important Battle of Poltava in 1709. This ended Mazepa's dream of independence.

After this battle, the Hetmanate's freedom became very limited. Russia started to control its internal affairs more strictly.

The End of the Zaporozhian Host

Under Catherine II of Russia, the Hetmanate's freedom was slowly taken away. In 1764, the position of Hetman was officially ended by the Russian government. Its duties were taken over by a Russian-controlled board called the Little Russian Collegium. This fully brought the Hetmanate into the Russian Empire.

On May 7, 1775, Empress Catherine II ordered the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich. On June 5, 1775, Russian troops surrounded the Sich and destroyed it. The Cossacks were disarmed, and their records were taken. Their leader, Petro Kalnyshevsky, was arrested. This marked the final end of the Zaporozhian Cossacks.

Culture and Daily Life

The Hetmanate was a time of great cultural growth in Ukraine. This was especially true during the rule of Hetman Ivan Mazepa.

Learning and Schools

Visitors from other countries were often surprised by how many people could read and write in the Hetmanate. There were more elementary schools per person than in Russia or Poland. In the 1740s, out of 1,099 towns, 866 had primary schools.

A German visitor in 1720 noted that Hetman Danylo Apostol's son, who had never left Ukraine, spoke many languages. The Kyiv Collegium became a leading educational center under Mazepa. It taught a classic Western education, often using Polish and Latin. Many scholars from Kyiv later moved to Moscow, helping to improve culture there too. A music academy was also founded in 1737 in Hlukhiv, the Hetmanate's capital at the time.

New printing presses were set up in places like Novhorod-Siverskyi and Chernihiv. Most books were religious, but some local history books were also written.

Religion

In 1620, the Orthodox Church in Kyiv was re-established. In 1686, the Orthodox Church in Ukraine came under the authority of the Patriarch of Moscow. However, local Church leaders still tried to keep their independence.

Hetman Ivan Mazepa had a close relationship with Metropolitan Varlaam Iasynsky. Mazepa gave a lot of land and money to the Church. He also paid for the building of many churches in Kyiv, like the Church of the Epiphany and the cathedral of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery. He also helped restore older churches, like Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, in the Ukrainian Baroque style.

Society in the Hetmanate

The people in the Hetmanate were divided into five main groups: nobles, Cossacks, clergy, townspeople, and peasants.

Nobles

Nobles were the most powerful social group. During the Khmelnytsky Uprising, many Polish nobles left the Hetmanate. The new noble class included old noble families who stayed and Cossack officers who became wealthy.

These nobles were called the Distinguished Military Fellows. Their status depended on their loyalty to the Hetmanate, not just their family history. Over time, their lands and privileges became hereditary, and they owned large estates.

Cossacks

Most Cossacks remained free soldiers. However, there were often tensions between the poorer Cossacks and the wealthier ones. These tensions sometimes led to rebellions, especially during "the Ruin." Russia often used these disagreements to its advantage. The Zaporizhian Sich was a safe place for Cossacks who wanted to escape the Hetmanate's control.

Clergy

During the Hetmanate, Catholic priests were removed from Ukraine. The "black" (monastic) Orthodox clergy had a very high status. Monasteries owned 17% of the Hetmanate's land and were free from taxes. They were as wealthy and powerful as the richest nobles. The "white" (married) Orthodox clergy were also tax-free. It was common for nobles or Cossacks to become priests and vice versa.

Townspeople

Twelve cities in the Hetmanate had Magdeburg rights. This meant they could govern themselves, control their own courts, finances, and taxes. Wealthy townspeople could hold government positions or even buy noble titles. Since the towns were small, this group was not as large or powerful as others.

Peasants

Peasants made up most of the Hetmanate's population. The Khmelnytsky Uprising greatly reduced forced labor by peasants. However, peasants working for nobles loyal to the Hetman or for the Orthodox Church still had to provide services.

About 50% of the land was given to Cossack officers or was controlled by free peasant villages. Cossack officers and nobles owned 33% of the land, and the Church owned 17%. Over time, nobles and officers gained more land. Peasants had to work more days for their landlords, but they were never fully enslaved and could still move freely until the end of the Hetmanate.

How the Hetmanate Was Organized

The Hetmanate was divided into military-administrative areas called regimental districts (polki). The number of these districts changed over time. In 1649, there were 16 districts. After losing Right-bank Ukraine, this number dropped to ten.

Each regimental district was further divided into companies (sotnias), led by captains (sotnyk). Companies were named after their location or leader and varied in size.

The first regimental divisions were set up in 1515. In 1625, six regimental districts were confirmed by the Treaty of Kurukove. By the Treaty of Zboriv, there were 23 regiments. After the Truce of Andrusovo in 1667, Russia gained 10 regiments in Left-bank Ukraine, including Kyiv.

The capital city was Chyhyryn. After the Treaty of Andrusovo, the capital moved to Baturyn in 1669. After the Baturyn's tragedy in 1708, when the Russian army destroyed Baturyn, Hlukhiv became the Hetman's official residence.

Polish was often used for administration and military commands. In 1764-65, the Cossack Hetmanate and Sloboda Ukraine were officially ended. They became part of the Russian Empire, and their administration was changed to be like other Russian provinces.

Government and Leadership

The highest power in the state belonged to the General Cossack (Military) Council. The head of the state was the Hetman. There was also an important advisory group called the Council of Officers (Starshyna).

At first, the Hetman was chosen by the General Council, which included all Cossacks, townspeople, clergy, and even peasants. But by the late 1600s, the Council of Officers mostly chose the Hetman. After 1709, the Tsar had to approve the Hetman's choice.

The Hetman had full power over the government, courts, money, and army. He could also conduct foreign policy, though Russia limited this right more and more in the 1700s.

Each regimental district was led by a colonel. The colonel was both the top military and civil leader in his area. Initially, Cossacks elected their colonels, but by the 1700s, the Hetman appointed them. After 1709, Moscow often chose the colonels. Each colonel had a staff, including a second-in-command, a judge, and a chancellor.

Throughout the 1700s, the Hetmanate's local freedom slowly disappeared. After the Baturyn's tragedy, its independence was greatly reduced. After the Battle of Poltava, Hetmans had to be approved by the Tsar and had less power.

The First Little Russian Collegium

In 1722, Russia created the Little Russian Collegium. This was a group of six Russian military officers stationed in the Hetmanate. They acted as a parallel government, supposedly to protect ordinary Cossacks and peasants from their officers.

When the Cossacks elected Pavlo Polubotok as Hetman, who opposed these changes, he was arrested and died in prison. The Little Russian Collegium then ruled the Hetmanate until 1727, when it was abolished. A new Hetman, Danylo Apostol, was then elected.

In 1659, a set of 28 rules was adopted that defined the relationship between the Hetmanate and Russia. These rules stayed in place until the Hetmanate ended. When Danylo Apostol became Hetman, new rules called the "28 Authoritative Ordinances" were signed. These rules stated that:

- The Hetmanate could not conduct its own foreign relations, except for border issues with Poland, the Crimean Khanate, and the Ottoman Empire, as long as it didn't go against Russian treaties.

- The Hetmanate kept ten regiments, but only three mercenary regiments were allowed.

- During wartime, Cossacks had to serve under the Russian commander.

- A court was set up with three Cossacks and three Russian government appointees.

- Russians and other non-local landowners could stay in the Hetmanate, but no new peasants from the north could be brought in.

The Second Little Russian Collegium

In 1764, Catherine II of Russia abolished the Hetman's office. Its power was replaced by the second Little Russian Collegium. This Collegium had four Russian appointees and four Cossack representatives, led by Pyotr Rumyantsev. He slowly but surely removed the last bits of local freedom.

In 1781, the regimental system was ended. Two years later, peasants' freedom to move was restricted, and they became fully tied to the land. Cossack soldiers joined the Russian army, and Cossack officers became Russian nobles. Lands were taken from the Church (which owned 17% of the region's land) and given to the nobility. The Hetmanate's territory was reorganized into three Russian provinces, just like any other part of the Russian Empire.

Foreign Relations

Bohdan Khmelnytsky's Foreign Policy

Bohdan Khmelnytsky tried to have good relationships with many different countries for the new Ukrainian Cossack state. He thought about making the Cossack state fully independent or allied with another strong country.

One idea was to create an "anti-Catholic block" with Orthodox and Protestant states like Russia, Moldavia, Wallachia, Transylvania, and Sweden. Another idea was to make the Cossack Hetmanate an equal partner in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He also considered bringing Ukraine into the Ottoman Empire's influence, like other states in the region.

Early in the uprising, Khmelnytsky got military help from the Crimean Khanate. This help was very important against the Polish forces. However, the Crimean Tatars were not always reliable allies. They sometimes prevented Cossack victories because they wanted to keep both Poland and the Cossack state weak.

From the start, Khmelnytsky also asked Russia for help. Russia did not give military aid for almost six years. Khmelnytsky also wrote to the Ottomans, who made vague promises of military support. He even asked the Sultan to accept him as a subject. By 1653, it was clear that the Ottomans would not fully commit. Khmelnytsky used his letters from the Sultan to pressure the Tsar into accepting the Hetmanate under Russian protection. The Pereyaslav Agreement in 1654 brought Ukraine under Russian protection and led to a war between Poland and Russia. Even after this treaty, Khmelnytsky continued to talk with the Ottomans, trying to play Russia and the Ottomans against each other.

Vyhovsky and Doroshenko's Foreign Policy

After Bohdan Khmelnytsky died in 1657, Ukraine became very unstable. There were conflicts between Cossacks who favored Poland and those who favored Russia. In 1658, Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky tried to create a three-part Commonwealth with Poland and Lithuania, making the Hetmanate an equal partner. But Vyhovsky's fall meant this plan never happened.

By 1660, the state was split along the Dnieper River, with Poland controlling the west and Russia controlling the east. In 1663, Cossacks rebelled against Poland. With help from the Crimean Tatars, Hetman Petro Doroshenko took power in 1665. He hoped to free Ukraine from both Russia and Poland.

The Truce of Andrusovo in 1667, signed by Russia and Poland, ignored the Hetmanate's interests and divided it. In 1666, Doroshenko started talking with the Ottomans again.

The Ottoman Empire saw the Truce of Andrusovo as a threat and became more active in the region. In 1668, Doroshenko became the sole Hetman of all Ukraine. He decided to place Ukraine under Ottoman protection. After talks, it was agreed that no Ottoman soldiers would be stationed in Ukraine, and Ukraine would not have to pay tribute. Doroshenko also wrote 17 articles outlining how he would accept Ottoman protection.

In 1672, the Ottomans declared war on Poland and marched north with Doroshenko's Cossacks and the Crimean Tatars. After the war, the Ottomans signed a treaty with Poland, giving the region of Podolia to the Ottomans. Later, in the Treaty of Karlowitz, Podolia was returned to Poland. In 1674, Russia invaded the Hetmanate. The Ottomans and Crimean Tatars sent armies to confront the Russians. The Russians withdrew, but the Ottomans destroyed settlements that had been friendly to the Russians. Doroshenko surrendered to the Russians two years later, in 1676.

Even though the Ottomans, Poles, and Russians knew that the Cossack Hetmanate was making alliances with multiple sides, they often pretended not to notice. The Ottomans did not keep a strong military presence in Ukraine because they preferred a buffer zone. The Ottomans called the Cossack Hetmanate "the country of Ukraine." Historians describe the relationship as a "vassal" state, meaning the Hetmanate had mutual duties with the Ottomans, like military service when needed, in exchange for protection.

See also

In Spanish: Hetmanato cosaco para niños

In Spanish: Hetmanato cosaco para niños

- Hetmans of Ukrainian Cossacks

- Sloboda Ukraine

- Zaporozhian Cossacks

- Zaporizhian Sich

- Zaporozhia (region)

- List of Ukrainian rulers

- List of voivodes of Nizhyn

Images for kids

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |