Byzantine–Ottoman wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Byzantine–Ottoman wars |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the rise of the Ottoman Empire and the decline of the Byzantine Empire | |||||||

|

Clockwise from top-left: Walls of Constantinople, Ottoman Janissaries, Byzantine flag, Ottoman bronze cannon |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

The Byzantine–Ottoman wars were a long series of battles between the Ottoman Turks and the Byzantine Greeks. These wars led to the complete end of the Byzantine Empire and the rise of the powerful Ottoman Empire.

The Byzantine Empire was already weak, especially after the Fourth Crusade in 1204. This event had split their empire into smaller parts. Even under the Palaiologos Dynasty, the Byzantines could not fully recover. They suffered many defeats against the Ottomans. Finally, their capital city, Constantinople, fell in 1453. This marked the formal end of the wars. However, some small Byzantine areas held out until 1479.

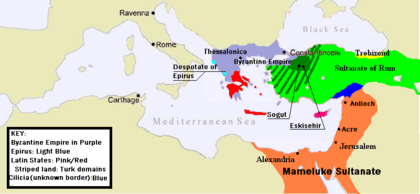

The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum had been taking land in western Anatolia. But the Nicaean Empire pushed them back from some Byzantine areas. In 1261, Constantinople was taken back from the Latin Empire by the Nicaean Empire. Even so, the Byzantine Empire faced threats in Europe from rivals like Epirus, Serbia, and Bulgaria. The Sultanate of Rum, Byzantium's main rival in Asia Minor, was also getting weaker. This caused Byzantium to move troops from Anatolia to protect its lands in Europe, especially Thrace.

The weakening of the Sultanate of Rum led to problems on the Anatolian border. Local leaders called ghazis (warriors for Islam) started taking land from the Byzantine Empire. Many Turkish leaders, known as beys, conquered Byzantine and Seljuk lands. But the lands controlled by one bey, Osman I, became the biggest threat to Nicaea and Constantinople. Within 90 years of Osman I starting the Ottoman state, the Byzantines lost all their land in Anatolia. By 1400, Byzantine power only reached Morea, a few Aegean islands, and a small area around Constantinople.

Events like the Crusade of Nicopolis in 1396, Timur's invasion in 1402, and the Crusade of Varna in 1444 helped Constantinople survive a bit longer. But it finally fell in 1453. After the city was captured, the Ottoman Empire became the main power in the eastern Mediterranean Sea.

Contents

The Rise of the Ottomans: 1265–1328

After the Byzantines took back Constantinople in 1261, their empire was left isolated. Other European states, especially Latin ones, still wanted to retake Constantinople. To the north, Serbia was also expanding into the Balkans.

The Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII, tried to make his rule stronger. He had his younger co-emperor, John IV, blinded, which made many people angry. To fix this, he tried to make peace with the Catholic Church in Rome. This was to reduce the threat from Latin states. But as the Byzantine Empire fought in Europe, the Turks under Osman I began raiding Byzantine lands in Anatolia. Söğüt and Eskişehir were captured in 1265 and 1289. Michael VIII could not stop these early attacks because he needed his troops in the West.

In 1282, Michael VIII died, and his son Andronikos II became emperor. People were relieved when Michael died because his policies, like heavy taxes and military spending, had been a burden. As the Ottoman Turks took land, many Anatolians saw them as liberators and converted to Islam. This weakened the Byzantine Empire's power base.

Andronikos II's rule was full of bad decisions. He lowered the value of Byzantine money, which hurt the economy. Taxes were reduced for rich landowners but increased for knights. To gain popularity, he ended the union of the Orthodox and Catholic Churches. This made relations with Latin states worse. Andronikos II tried to protect Byzantine lands in Asia Minor. He built forts and trained his army. But his general, Alexios Philanthropenos, tried to overthrow him. This failed, and Alexios was blinded, ending his campaigns. This allowed the Ottomans to besiege Nicaea in 1301.

The Byzantines suffered more defeats at Magnesia and Bapheus in 1302. Andronikos tried again, hiring Catalan mercenaries. These 6,500 soldiers, led by Roger de Flor, pushed back the Turks in 1303. They drove the Turks from Philadelphia to Cyzicus, causing much damage. But these gains were lost when Roger de Flor was killed. His mercenaries then plundered the countryside. When they left in 1307, the locals welcomed the Ottomans, who again blocked key fortresses. The Ottomans succeeded because their enemies were divided. Many peasants in Anatolia preferred Ottoman rule.

After these defeats, Andronikos II could not send many troops. In 1320, his grandson, Andronikos III, was removed from inheriting the throne. The next year, Andronikos III marched on Constantinople and was given Thrace to rule. He kept pushing for more power and became co-emperor in 1322. This led to a civil war where Serbia supported Andronikos II and Bulgaria supported his grandson. Andronikos III finally won on May 23, 1328. While he was securing his power, the Ottomans captured Bursa from the Byzantines in 1326.

Byzantium's Struggle: 1328–1341

The city of Nicaea was doomed when the Byzantine army was defeated at Pelekanos on June 10, 1329. In 1331, Nicaea surrendered. This was a huge loss, as it had been the capital of the Empire just 70 years before.

The Byzantine military was weak again. Andronikos III had to use diplomacy, just like his grandfather. He agreed to pay tribute to the Ottomans to keep the remaining Byzantine towns in Asia Minor safe. But this did not stop the Ottomans from besieging Nicomedia in 1333. The city finally fell in 1337.

Despite these losses, Andronikos III had some successes in Greece and Asia Minor. He brought Epirus and Thessaly back under Byzantine control. In 1329, the Byzantines captured Chios, and in 1335, they secured Lesbos. However, these islands were exceptions. The general trend was increasing Ottoman conquests. None of these islands were part of the Ottoman lands at the time. Their capture showed what the Byzantines could do under Andronikos III. But Byzantine military power would soon be weakened by Serbian expansion and a terrible civil war. This war would make the Byzantine Empire a vassal (a state controlled by another) of the Ottomans.

Balkan Invasion and Civil War: 1341–1371

Andronikos III died in 1341, leaving his 10-year-old son, John V, to rule. A group of regents (people who rule for a young king) was set up. Rivalries among these regents led to a destructive civil war. John Cantacuzenus eventually won in Constantinople in February 1347. During this time, the plague, earthquakes, and Ottoman raids continued. Only Philadelphia remained in Byzantine hands, and only by paying tribute.

Throughout the civil war, both sides used Turkish and Serbian mercenaries. These mercenaries plundered the land, leaving much of Macedonia in ruins. After his victory, Cantacuzenus ruled as co-emperor with John V. The civil war caused famine and suffering. The Turks raided from Asia, taking people and animals, leaving many areas empty.

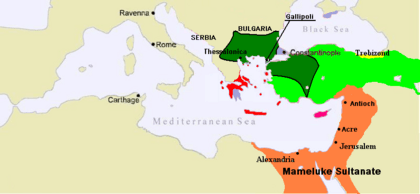

This shared rule eventually failed, leading to a new civil war. This further weakened Byzantium. John VI Cantacuzenus won again. But the Turks, led by Osman I's son, Orhan I, captured the fort of Kallipolis (Gallipoli) in 1354. This gave them access to Europe. The arrival of the powerful Ottoman soldiers near Constantinople caused panic. John V took advantage of this. With help from the Genoese, he overthrew John VI Cantacuzenus in November 1354. John VI later became a monk.

The civil war did not end there. Matthew Cantacuzenus, John VI's son, got troops from Orhan and tried to take Constantinople. But he was captured in 1356. This ended his dream of being emperor and was a small setback for the Ottomans. After the civil conflict, there was a brief pause in fighting. In 1361, Didymoteichon fell to the Turks. Orhan's successor, Murad I, was more focused on his lands in Anatolia. But Murad I, like earlier Turkish leaders, let his vassals take Byzantine territory. Philippopolis fell between 1363–64, and Adrianople fell to the Ottomans in 1369.

The Byzantine Empire was too weak to fight back. By now, the Ottomans were very powerful. Murad I crushed a Serbian army at the Battle of Maritsa in 1371. This ended Serbian power. The Ottomans were now ready to conquer Constantinople. John V asked the Pope for help, offering to join the Roman Catholic Church for military support. But he received no help. So, John V had to make a deal with the Ottomans. Murad I and John V agreed that Byzantium would pay regular tribute in troops and money for its safety.

Byzantine Civil War and Vassalage: 1371–1394

By this time, the Ottomans had mostly won the war. Byzantium was reduced to a few towns besides Constantinople. It was forced to become a vassal state of the Ottoman Sultan. This continued until 1394. However, while Constantinople was weakened, other Christian powers still threatened the Ottomans. Also, Asia Minor was not fully under Ottoman control. The Ottomans continued their push into the Balkans. In 1385, Sofia was captured from the Bulgarians, and Niš was taken the next year. Many smaller states became Ottoman vassals, including the Serbs after the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. Much of Bulgaria was taken in 1393 by Bayezid I. By 1396, all of Bulgaria was under Ottoman rule when Vidin fell.

Ottoman advances in the Balkans were helped by more Byzantine civil conflicts. This time, it was between John V and his oldest son, Andronikos IV. Andronikos escaped with his son and got help from Murad by promising more tribute than John V. The civil war continued until 1390. John V eventually forgave Andronikos IV and his son in 1381. This angered his second son and heir, Manuel II Palaiologos. Manuel II seized Thessalonika, freeing parts of Greece from Ottoman rule. This worried the Ottoman Sultan.

Andronikos IV died in 1385. Thessalonika surrendered in 1387. This encouraged Manuel II Palaiologos to seek forgiveness from the Sultan and John V. His close relationship with John V angered John VII, who felt his right as heir was threatened. John VII launched a coup against John V. But despite Ottoman and Genoese help, his rule lasted only five months before Manuel II and his father overthrew him.

In 1390, Bayazid I sent a fleet to burn down Chios and nearby towns. He also attacked Euboea, parts of Attica, and the Aegean islands. He destroyed every town and village from Bithynia to Thrace, near Constantinople. He also forced all the people to leave.

Fall of Philadelphia

While the civil war raged, the Turks in Anatolia took Philadelphia in 1390. This marked the end of Byzantine rule in Anatolia. However, the city had only been under nominal Byzantine control for a long time. Its fall did not greatly affect the Byzantines strategically.

Vassalage

After John V's death, Manuel II Palaiologos secured his throne. He made good relations with the Sultan, becoming his tributary. In return for the Sultan accepting his rule, Manuel II had to tear down the fortifications at the Golden Gate. He was not happy about this.

Fighting Resumes: 1394–1424

In 1394, relations between the Byzantines and Ottomans worsened. The war restarted when Ottoman Sultan Bayezid (ruled 1389–1402) ordered Manuel II's execution. This was because the Emperor tried to make peace with his nephew, John VII. The Sultan then changed his mind. He demanded that a mosque and a Turkish settlement be built in Constantinople. Manuel II refused this. He also refused to pay tribute and ignored the Sultan's messages. This led to a siege of the city in 1394. Manuel II called for a Crusade, which arrived in 1396. But this Crusade, led by Sigismund, was defeated at Nicopolis in 1396.

The defeat convinced Manuel II to leave the city and seek help in Western Europe. During this time, John VII successfully defended the city against the Ottomans. The siege finally ended when Timur of the Chagatai Mongols led an army into Anatolia. He broke up the network of states loyal to the Ottoman Sultan. At the Battle of Ankara, Timur's forces crushed Bayezid I's army. This was a shocking defeat. After this, the Ottoman Turks began fighting among themselves, led by Bayezid's sons.

The Byzantines quickly took advantage of the situation. They signed a peace treaty with their Christian neighbors and with one of Bayezid's sons. By signing this treaty, they got back Thessalonika and much of the Peloponnese. The Ottoman civil war ended in 1413. Mehmed I, with Byzantine support, defeated his rivals.

The rare friendship between the two states did not last. Mehmed I died, and Murad II rose to power in 1421. At the same time, John VIII became the Byzantine emperor. Relations between them quickly worsened. Neither leader was happy with how things were. John VIII made a foolish move by starting a rebellion in the Ottoman Empire. He released a man named Mustafa, who claimed to be Bayezid's lost son.

Despite the odds, a large force gathered under Mustafa. They defeated Murad II's commanders. Murad II's angry response eventually crushed this rebellion. In 1422, he began the Siege of Thessalonika and Constantinople. John VIII then asked his aging father, Manuel II, for advice. The result was another rebellion in the Ottoman ranks. This time, they supported Murad II's brother, Kucuk Mustafa. This rebellion started in Asia Minor, with Bursa under siege. After a failed attack on Constantinople, Murad II had to turn his army back to defeat Kucuk. With these defeats, the Byzantines were forced into vassalage again. They had to pay 300,000 silver coins to the Sultan every year as tribute.

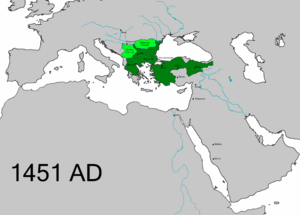

Ottoman Victory: 1424–1453

The Ottomans faced many enemies between 1424 and 1453. While besieging Thessalonika, they also had to fight the Serbs under George Brankovic, the Hungarians under John Hunyadi, and the Albanians under George Kastrioti Skanderbeg. This resistance led to the Crusade of Varna in 1444. Despite much local support, this Crusade was defeated.

In 1448 and 1451, there were changes in leadership. Murad II died and was replaced by Mehmed II 'the Conqueror'. Constantine XI Palaiologos became the new Byzantine emperor after John VIII. Constantine XI and Mehmed did not get along. Constantine XI's successful conquests in the Peloponnese worried Mehmed. Mehmed sent about 40,000 soldiers to stop these gains. Constantine XI threatened to rebel against Mehmed unless certain conditions were met. Mehmed responded by building forts in the Bosporus. This blocked Constantinople from getting help by sea. The Ottomans already controlled the land around Constantinople. So, they began an assault on the city on April 6, 1453.

Despite a union of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches, the Byzantines received no official help from the Pope or Western Europe. Only a few soldiers from Venice and Genoa arrived. England and France were finishing the Hundred Years War. Spain was in the final stages of its Reconquista (reconquest). The Holy Roman Empire had used up its resources at Varna. Further fighting among German princes and the Hussite wars made them unwilling to join a crusade. Poland and Hungary were busy after their defeat at Varna.

The only other major European powers were the Italian city-states. Genoa and Venice were enemies of the Ottomans, but also of each other. Venice considered sending its fleet to attack the forts guarding the Dardanelles and Bosporus. But the force was too small and arrived too late. The Ottomans would have overpowered any military help from one city, even a powerful one like Venice. Still, about 2,000 mercenaries, mostly Italian, arrived to help defend the city. The city's defense relied on these mercenaries and 5,000 militia soldiers. The city's population had shrunk due to heavy taxes, plague, and civil conflict. The defenders were poorly trained but well-armed. However, they lacked cannons to match the Ottomans' artillery.

The city did not fall because of Ottoman artillery or naval power. Many Italian ships were able to help and then escape. The fall of Constantinople happened because of the overwhelming odds against the city. The defenders were outnumbered more than ten to one. They were overcome by sheer exhaustion and the skill of the Ottoman Janissaries. As the Ottomans continued their costly attacks, many in their camp doubted the siege's success. History showed the city was hard to conquer. To boost morale, the Sultan gave a speech, reminding his troops of the city's vast wealth and the chance to plunder it. An all-out assault captured the city on May 29, 1453.

After the siege, the Ottomans went on to take Morea in 1460 and Trebizond in 1461. With the fall of Trebizond, the Roman Empire officially ended. European leaders continued to recognize the Palaiologoi as the rightful emperors of Constantinople until the 16th century. By then, the Reformation and the Ottoman threat forced European powers to accept the Ottoman Empire as masters of Anatolia and the Levant. Byzantine rule in its former areas fully ended after the conquest of several remaining states: Trebizond in 1461, Theodoro in 1475, and Epirus in 1479.

Why Byzantium Lost

Latin Intervention

The presence of Latin (Western European) states in the Balkans seriously hurt Byzantium's ability to fight the Ottoman Turks. For example, Michael VIII Palaiologos tried to push the Latins out of Greece. This meant he had to move troops away from the Anatolian borders. This allowed several Turkish states, including Osman I's, to raid and settle former Byzantine lands. Andronikos II's campaigns in Anatolia, even when successful, were often stopped by events in the western part of the Empire. The Byzantines had to choose between attacks from the Pope and Latin states or an unpopular union with the Catholic Church. This situation was used by rivals to try and overthrow the Byzantine Emperor.

However, by the mid-to-late 14th century, the Byzantines started getting some help from the West. This was mostly sympathy for a fellow Christian power fighting a Muslim one. But despite two Crusades, the Byzantines "received as much help from Rome as we did from the [Mamluk] sultan [of Egypt]". The Mamluk Sultanate in the 13th century was very determined to remove Christian influence from the Middle East. Raids by Cyprus did not change this in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Byzantine Weakness

After the Fourth Crusade, the Byzantines were in a very unstable position. Taking back Constantinople in 1261 and later campaigns happened at a bad time. The weakening of the Sultanate of Rum led to many smaller states, like the one founded by Osman I, breaking away. This weakening of unified Turkish power gave the Empire of Nicaea a temporary advantage.

To take back Greek lands, Michael VIII had to put heavy taxes on the farmers in Anatolia. This was to pay for his expensive army. This led many farmers to support the Turks, who initially had lower taxes.

After Michael VIII died, the Byzantines suffered from constant civil wars. The Ottomans also had civil conflicts, but much later, in the 15th century. By then, the Byzantines were too weak to take back much land. The Byzantine civil wars (1341–1371) happened when the Ottomans were crossing into Europe and surrounding Constantinople. This sealed the city's fate as a vassal. When the Byzantines tried to break free, they found themselves outmatched. They relied on Latin help, which, despite two Crusades, ultimately did not amount to much.

Ottoman Advantages

Ottoman rule was often preferred by Anatolian commoners because of the heavy Byzantine taxes. This allowed the Ottomans to gather many willing soldiers. At first, their raids gained them support from other Turks near Osman's small territory. Over time, as the Turks settled in lands once held by the Byzantines, they used the hardships of the peasant classes to recruit them. Those who did not help the Ottomans were raided themselves. Eventually, cities in Asia Minor, isolated from the more organized cities in the western Byzantine Empire, surrendered. During their conquests, the Ottomans became very skilled at siege warfare because many of these cities had walls.

The Ottomans' relaxed way of ruling new conquests allowed them to expand quickly. Unlike the Byzantines' highly centralized government, the Ottomans often made their opponents vassals instead of destroying them. This way, they did not exhaust themselves. They demanded tribute from conquered states, often in the form of children and money. This was effective in forcing submission rather than full conquest. Also, the region had many separate states (Bulgaria, Serbia, Latin states) that often fought each other as much as they fought the Ottomans. They realized too late that the Ottoman forces defeated them by bringing them into a network of controlled states.

Consequences

The Fall of Constantinople shocked the Pope. He immediately called for a crusade to counter-attack. Only Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, responded. But he would only go if a powerful monarch helped him, and none would. Pope Pius II then ordered another crusade. Again, no major European leaders made significant efforts. This forced the Pope himself to lead a crusade. His death in 1464 led to the crusade being abandoned at the port of Ancona.

The fall of Constantinople also had many effects in Europe. Many Greek scholars and their knowledge moved to Europe, escaping the Ottomans. This was a key factor in starting the European Renaissance.

By 1529, Europe began to face the Ottoman threat more seriously. Martin Luther, changing his views, wrote that the "Scourge of God" (referring to the Ottomans) had to be fought strongly by secular leaders, not just through Crusades led by the Pope.

With Europe accepting the Ottomans' control of Constantinople, the Ottomans continued their conquests in Europe and the Middle East. Their power reached its peak in the mid-17th century. However, the very success of their elite soldiers, the Janissaries, became a weakness. Their resistance to change made it hard for the Ottoman Empire to modernize. Meanwhile, European armies became more resourceful and modern. As a result, attempts by the Russian and Austrian Empires to contain the Ottomans became more and more successful. The Empire finally dissolved after World War I.

See also

In Spanish: Guerras turco-bizantinas para niños

In Spanish: Guerras turco-bizantinas para niños

- Byzantine empire

- Ottoman empire

- Ottoman Navy

- Arab–Byzantine wars

- Byzantine–Seljuq wars

- List of conflicts in the Middle East

- Ottoman claim to Roman succession

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |