John Hunyadi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids John Hunyadi |

|

|---|---|

|

|

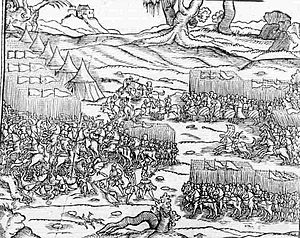

John Hunyadi depicted in the 15th-century Chronica Hungarorum (Brno, 1488)

|

|

| Born | c. 1406 |

| Died | 11 August 1456 (aged 49–50) Zimony, Kingdom of Hungary (now Zemun, Serbia) |

| Burial | St. Michael's Catholic Cathedral, Gyulafehérvár, Kingdom of Hungary (now Alba Iulia, Romania) |

| Spouse | Erzsébet Szilágyi |

| Issue | |

| House | House of Hunyadi |

| Father | Voyk |

| Mother | Erzsébet Morzsinai |

| Signature | |

John Hunyadi (Hungarian: Hunyadi János; Romanian: Ioan de Hunedoara; Croatian: Janko Hunjadi; Serbian: Сибињанин Јанко, romanized: Sibinjanin Janko; c. 1406 – 11 August 1456) was a very important military leader and politician in Hungary during the 1400s. He served as a regent (a ruler for a young king) of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1446 to 1453. He ruled while the young king, Ladislaus V, was still a child.

Most old records say that John Hunyadi came from a noble family with roots in Wallachia. He became famous for fighting against the powerful Ottoman Empire. People even called him the "Turk-buster" because of his many victories. He received a lot of land and became very wealthy. He used his great wealth and power mainly to fight the Ottomans in the Hungarian–Ottoman Wars.

Hunyadi learned his military skills on the southern borders of Hungary. These areas were often attacked by the Ottomans. He became the Ban of Szörény in 1439. Then, in 1441, he was made Voivode of Transylvania, Count of the Székelys, and Chief Captain of Nándorfehérvár (now Belgrade). He also became the head of several southern counties. This meant he was in charge of defending the borders.

He used new fighting methods, like the Hussite way of using wagons as mobile forts. He hired professional soldiers and also called on local farmers to fight. These new ideas helped him win his first battles against Ottoman raiders in the early 1440s.

Contents

Early Life and Family History

When and Where Was John Hunyadi Born?

The first time John Hunyadi is mentioned is in a royal paper from October 18, 1409. In this paper, King Sigismund of Hungary gave Hunyad Castle (in today's Hunedoara, Romania) and its lands to John's father, Voyk, and four of Voyk's relatives, including John. The paper says John's father was a "court knight," meaning he came from a respected family.

Two writers from the 1400s, Johannes de Thurocz and Antonio Bonfini, wrote that Voyk moved from Wallachia to Hungary because King Sigismund asked him to. Many historians today agree that John Hunyadi's father was from Wallachia. However, some historians believe Voyk was from the area around Hunyad Castle itself.

Who Were John Hunyadi's Parents?

Antonio Bonfini also mentioned a different story about John Hunyadi's parents. He said it was just a "silly tale" made up by Hunyadi's enemy, Ulrich II, Count of Celje. This story claimed John was actually King Sigismund's secret son, not Voyk's. This tale became popular later, especially when John Hunyadi's son, Matthias Corvinus, became king. Matthias even put up a statue of King Sigismund in Buda. Most modern historians think this story is just gossip.

It's even harder to know for sure who John Hunyadi's mother was. Some stories say she was the daughter of a rich nobleman from Morzsina (today's Margina, Romania). Her name might have been Elisabeth. Another idea is that she was a distinguished Greek lady. This might just mean she followed the Orthodox Christian faith.

John Hunyadi's birth year is not certain. Some say he was born in 1390, but he was likely born between 1405 and 1407. This is because his younger brother was born after 1409, and a nearly 20-year age gap between brothers seems unlikely. His birthplace is also unknown. One writer from the 1500s said John Hunyadi was from the Hátszeg region (now Țara Hațegului in Romania). John's father died before February 12, 1419.

Becoming a Great General

Early Military Training (1420–1438)

Andreas Pannonius, who worked for Hunyadi, wrote that the future leader "learned to handle both cold and heat well." Like other young noblemen, John Hunyadi spent his youth working for powerful lords. But the exact details of his early career are not fully clear.

Some accounts say he started serving under Filippo Scolari, who was in charge of defending the southern border, around 1420. Others suggest he served under Nicholas of Ilok. Another writer, Antonio Bonfini, said Hunyadi worked for either Demeter Csupor, Bishop of Zagreb, or the Csákys.

The Byzantine historian Laonikos Chalkokondyles wrote that young Hunyadi "stayed for a time" at the court of Stefan Lazarević, the ruler of Serbia, who died in 1427. Hunyadi's marriage to Elisabeth Szilágyi supports this, as her father worked for the Serbian ruler around 1426. Their wedding happened around 1429.

While still young, Hunyadi joined the group of people serving King Sigismund. He went with Sigismund to Italy in 1431. There, Sigismund ordered him to join the army of Filippo Maria Visconti, the Duke of Milan. Hunyadi served in the Duke's army for two years. Historians believe Hunyadi learned a lot about modern warfare and using hired soldiers (mercenaries) in Milan.

Hunyadi rejoined Emperor Sigismund's group in late 1433. He served as a "court knight." He even loaned 1,200 gold florins to the Emperor in January 1434. In return, Sigismund gave Hunyadi and his younger brother control over some lands and half of the royal income from a ferry on the Maros River. The royal document called Hunyadi "John the Vlach" (meaning Romanian). Sigismund also gave Hunyadi more lands, including about 10 villages.

Hunyadi also served a Croatian nobleman named Franko Talovac, who was the Ban of Severin. During this time, a Vlach district in the Banate of Severin was given to Hunyadi.

In October 1437, Sigismund hired Hunyadi and 50 of his soldiers for three months. This suggests Hunyadi went with the King to Bohemia. It seems Hunyadi studied the tactics of the Hussites there, especially their use of wagons as a mobile fort. King Sigismund died on December 9, 1437. His son-in-law, Albert, was elected King of Hungary. Hunyadi soon returned to the southern borders, which were being attacked by the Ottomans.

First Fights Against the Ottomans (1438–1442)

The Ottomans had taken over most of Serbia by the end of 1438. That same year, Ottoman troops, helped by Vlad II Dracul, the Prince of Wallachia, attacked Transylvania. They looted towns like Hermannstadt/Nagyszeben and Gyulafehérvár (today's Alba Iulia, Romania). In June 1439, the Ottomans surrounded Smederevo, a key Serbian fort. Đurađ Branković, the ruler of Serbia, fled to Hungary to ask for help.

King Albert called on all noblemen to fight the Ottomans, but few showed up. John Hunyadi was an exception. He led attacks against the Ottoman forces and won small battles, which made him more famous. The Ottomans captured Smederevo in August. King Albert then made John Hunyadi and his brother Bans of Severin, giving them the rank of "true barons of the realm."

King Albert died on October 27, 1439. His wife, Elizabeth of Luxembourg, gave birth to a son, Ladislaus the Posthumous, after his death. The Hungarian nobles offered the crown to Vladislaus, the King of Poland. But Elizabeth had her baby son crowned king in May 1440. Vladislaus still accepted the offer and was also crowned king in July. This led to a civil war. Hunyadi supported King Vladislaus. He fought the Ottomans in Wallachia, and King Vladislaus rewarded him with five new lands in August 1440.

Hunyadi and Nicholas of Ilok defeated Vladislaus's enemies at Bátaszék in early 1441. This victory largely ended the civil war. King Vladislaus was grateful and made Hunyadi and Nicholas joint Voivodes of Transylvania and Counts of the Székelys in February. Soon after, the King also put them in charge of Temes County and gave them command of Belgrade and other castles along the Danube River.

Since Nicholas of Ilok spent most of his time at the royal court, Hunyadi mostly managed Transylvania and the southern borders by himself. He quickly visited Transylvania to calm things down there. Because of his good leadership, the areas he managed were peaceful, allowing him to focus on defending the borders. He also helped local landowners at the royal court, which made him popular.

Hunyadi began repairing the walls of Belgrade, which had been damaged by an Ottoman attack. To get back at the Ottomans for raiding the Sava River area, he led an attack into Ottoman lands in the summer or autumn of 1441. He won a major battle against Ishak Bey, the commander of Smederovo.

In early 1442, Bey Mezid attacked Transylvania with 17,000 soldiers. Hunyadi was surprised and lost the first battle near Marosszentimre (Sântimbru, Romania). Bey Mezid then surrounded Hermannstadt, but Hunyadi's forces, joined by Újlaki, made the Ottomans leave. The Ottoman army was completely defeated at Gyulafehérvár on March 22.

Pope Eugenius IV wanted a new crusade against the Ottomans. He sent his representative, Cardinal Giuliano Cesarini, to Hungary. The Cardinal arrived in May 1442 to help King Vladislaus and Queen Elisabeth make peace. The Ottoman Sultan, Murad II, sent Şihabeddin Pasha, the governor of Rumelia, to invade Transylvania with 70,000 soldiers. The Pasha boasted that just seeing his turban would make his enemies run away. Even though Hunyadi only had 15,000 men, he completely defeated the Ottomans at the Ialomița River in September. John Hunyadi and his 15,000 men defeated the 80,000-strong army of Begler Bey Sehabeddin at Zajkány (today's Zeicani), near the Iron Gate of the Danube River in 1442. Hunyadi placed Basarab II on the throne of Wallachia, but Basarab's enemy Vlad Dracul soon returned and forced Basarab to flee in early 1443.

Hunyadi's victories in 1441 and 1442 made him a famous enemy of the Ottomans and known across all of Christendom. He always attacked fiercely, which helped him win even when the Ottomans had more soldiers. He used hired soldiers, including former Czech Hussite troops, which made his army more professional. He also used many local farmers, whom he was not afraid to use in battle.

Leading the Fight Against the Ottomans

The "Long Campaign" (1442–1444)

In April 1443, King Vladislaus and his nobles decided to launch a major campaign against the Ottoman Empire. Cardinal Cesarini helped Vladislaus make a truce with Frederick III of Germany, who was the guardian of the young Ladislaus V. This truce meant Frederick III would not attack Hungary for the next year.

Hunyadi spent about 32,000 gold florins of his own money to hire over 10,000 hired soldiers. The King also gathered troops, and more soldiers arrived from Poland and Moldavia. The King and Hunyadi led an army of 25,000–27,000 men on the campaign in the autumn of 1443. While Vladislaus was officially in command, Hunyadi was the real leader. Despot Đurađ Branković joined them with 8,000 men.

Hunyadi led the front lines and defeated four smaller Ottoman forces, stopping them from joining together. He captured Kruševac, Niš, and Sofia. However, the Hungarian troops could not get through the passes of the Balkan Mountains to Edirne. Cold weather and a lack of supplies forced the Christian troops to stop the campaign at Zlatitsa. After winning the Battle of Kunovica, they returned to Belgrade in January and Buda in February 1444.

The Battle of Varna (1444)

Even though no major Ottoman armies were completely destroyed, Hunyadi's "long campaign" created excitement across Christian Europe. Pope Eugenius, Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, and other European powers called for a new crusade. They promised money or military help. A group of nobles and church leaders formed under Hunyadi's leadership around this time. Their main goal was to defend Hungary against the Ottomans.

The Christian advance into Ottoman lands also encouraged people in the Balkan Peninsula to revolt. For example, Skanderbeg, an Albanian noble, drove the Ottomans out of Krujë and other forts. Sultan Murad II, who was busy with a rebellion in Anatolia, offered good peace terms to King Vladislaus. He even promised to remove Ottoman soldiers from Serbia, making it semi-independent again under Despot Đurađ Branković. He also offered a truce for ten years. Hungarian messengers accepted the Sultan's offer in Edirne on June 12, 1444.

Đurađ Branković, who was thankful for getting his lands back, gave his estates at Világos (today's Șiria, Romania) to Hunyadi on July 3. Hunyadi suggested King Vladislaus confirm the good treaty. However, Cardinal Cesarini urged the King to continue the crusade. On August 4, Vladislaus solemnly promised to launch a campaign against the Ottoman Empire before the end of the year, even if a peace treaty was made.

King Vladislaus, pushed by Cardinal Cesarini to keep his promise, decided to invade the Ottoman Empire in the autumn. He offered Hunyadi the crown of Bulgaria. The crusaders left Hungary on September 22. They planned to go towards the Black Sea through the Balkan Mountains. They hoped the Venetian fleet would stop Sultan Murad from moving Ottoman forces from Anatolia to the Balkans. But the Genoese helped the Sultan's army cross the Dardanelles.

The two armies met near Varna on November 10. Even though the crusaders were outnumbered two to one, they initially fought well against the Ottomans. However, the young King Vladislaus attacked the janissaries too early and was killed. The crusaders panicked, and the Ottomans destroyed their army. Hunyadi barely escaped the battlefield but was captured by Wallachian soldiers. However, Vlad Dracul soon set him free.

After the Battle of Varna (1445–1446)

At the next meeting of the Hungarian nobles (Diet) in April 1445, they decided that if King Vladislaus, whose fate was still unknown, did not return to Hungary by the end of May, they would all accept the child Ladislaus V as king. The nobles also chose seven "Captains in Chief," including Hunyadi. Each was responsible for bringing order back to their assigned region. Hunyadi was given the lands east of the Tisza River. He owned at least six castles and lands in about ten counties, making him the most powerful noble in his region.

Hunyadi planned to organize a new crusade against the Ottoman Empire. He sent many letters to the Pope and other Western rulers in 1445, asking for help. In September, he met with Waleran de Wavrin, a captain of Burgundian ships, and Vlad Dracul of Wallachia, who had taken small forts along the Lower Danube from the Ottomans. However, Hunyadi did not risk a direct fight with the Ottoman soldiers stationed on the south bank of the river. He returned to Hungary before winter. Vlad Dracul soon made peace with the Ottomans.

Hunyadi as Governor of Hungary (1446–1453)

The Hungarian nobles declared Hunyadi the regent, giving him the title "governor," on June 6, 1446. His election was mainly supported by the lesser nobles. By this time, Hunyadi had become one of the richest nobles in the kingdom. His lands covered a huge area, more than 800,000 hectares (about 2 million acres). Hunyadi was one of the few nobles who spent a lot of his own money to pay for the wars against the Ottomans.

As governor, Hunyadi could use most of the king's powers while King Ladislaus V was a minor. For example, he could give away land, but only up to a certain size. Hunyadi tried to bring peace to the border regions. Soon after becoming governor, he led an unsuccessful campaign against Ulrich II, Count of Celje. Count Ulrich was acting as the Ban of Slavonia without permission and refused to give up his title. Hunyadi could not force him to obey.

Hunyadi convinced John Jiskra of Brandýs, a Czech commander who controlled northern Hungary (today's Slovakia), to sign a three-year truce on September 13. However, Jiskra did not keep the truce, and fighting continued. In November, Hunyadi marched against Frederick III of Germany, who had refused to release Ladislaus V and had taken towns along the western border. Hunyadi's troops raided Austria, Styria, Carinthia, and Carniola, but there was no major battle. A truce with Frederick III was signed on June 1, 1447. Frederick still kept his role as the young King's guardian. The Hungarian nobles were disappointed, and the Diet elected Ladislaus II Garay, a leader of Hunyadi's opponents, as Palatine in September 1447.

Hunyadi sped up his talks with Alfonso the Magnanimous, the King of Aragon and Naples. He even offered Alfonso the crown of Hungary if the King would join an anti-Ottoman crusade and confirm Hunyadi's position as governor. However, King Alfonso did not sign an agreement.

Hunyadi invaded Wallachia and removed Vlad Dracul from power in December 1447. Hunyadi called himself "voivode of the Transalpine land" and referred to the Wallachian town of Târgoviște as "our fortress." He definitely put a new ruler in Wallachia. In February 1448, Hunyadi sent an army to Moldavia to help Peter take the throne. In return, Peter accepted Hunyadi's authority and helped put Hungarian soldiers in the fort of Chilia Veche on the Lower Danube.

Hunyadi tried again to remove Count Ulrich of Celje from Slavonia but could not defeat him. In June, Hunyadi and the Count reached an agreement that confirmed Count Ulrich's position in Slavonia. Soon after, Hunyadi sent messengers to the two most important Albanian leaders, Skanderbeg and his father-in-law, Gjergj Arianiti, to ask for their help against the Ottomans. Pope Eugenius suggested delaying the campaign. However, Hunyadi wrote on September 8, 1448, that he "had enough of our men enslaved" and was determined to drive "the enemy from Europe." He also explained his military plan to the Pope, saying that "Power is always greater when used in attack rather than in defence."

Hunyadi left for a new campaign with 16,000 soldiers in September 1448. About 8,000 soldiers from Wallachia also joined him. Since Đurađ Branković refused to help the crusaders, Hunyadi treated him as an Ottoman ally. His army marched through Serbia, taking supplies from the countryside. To stop Hunyadi and Skanderbeg's armies from joining, Sultan Murad II fought Hunyadi at Kosovo Polje on October 17. The battle, which lasted three days, ended with a terrible defeat for the crusaders. Around 17,000 Hungarian and Wallachian soldiers were killed or captured, and Hunyadi barely escaped. On his way home, Hunyadi was captured by Đurađ Branković, who held him prisoner in the fort of Smederevo. The Serbian ruler first thought about giving Hunyadi to the Ottomans. However, Hungarian nobles and church leaders meeting at Szeged convinced him to make peace with Hunyadi. Hunyadi had to pay a large sum of money (100,000 gold florins) and return all the lands he had taken from Đurađ Branković. Hunyadi's oldest son, Ladislaus, was sent to the Serbian ruler as a hostage. Hunyadi was released and returned to Hungary in late December 1448.

His defeat and the difficult treaty with the Serbian ruler weakened Hunyadi's position. The church leaders and nobles confirmed the treaty and asked Branković to talk with the Ottomans. Hunyadi resigned from his position as Voivode of Transylvania. He attacked the lands controlled by John Jiskra and his Czech hired soldiers in the autumn of 1449 but could not defeat them. However, the rulers of two nearby countries, Stjepan Tomaš, the King of Bosnia, and Bogdan II, the Voivode of Moldavia, made treaties with Hunyadi, promising to stay loyal to him. In early 1450, Hunyadi and Jiskra signed a peace treaty in Mezőkövesd. This treaty allowed many rich towns in Upper Hungary (like Pressburg/Pozsony, today's Bratislava, Slovakia, and Kassa, today's Košice, Slovakia) to remain under Jiskra's control.

At Hunyadi's request, the Diet of March 1450 ordered that Branković's lands in Hungary be taken away. Hunyadi and his troops went to Serbia, forcing Branković to release his son. Hunyadi, Ladislaus Garai, and Nicholas Újlaki made an agreement on July 17, 1450. They promised to help each other keep their positions if King Ladislaus V returned to Hungary. In October, Hunyadi made peace with Frederick III of Germany, which confirmed Frederick's role as guardian of Ladislaus V for another eight years. With help from Újlaki and other nobles, Hunyadi also made a peace treaty with Branković in August 1451. This allowed Hunyadi to buy back the disputed lands for 155,000 gold florins. Hunyadi launched a military attack against Jiskra, but the Czech commander defeated the Hungarian troops near Losonc (today's Lučenec, Slovakia) on September 7. With help from Branković, Hungary and the Ottoman Empire signed a three-year truce on November 20.

In late 1451 and early 1452, Austrian nobles rebelled against Frederick III of Germany, who was ruling Austria for Ladislaus the Posthumus. The leader of the rebellion, Ulrich Eizinger, asked for help from the nobles of Ladislaus's other lands, Bohemia and Hungary. The Hungarian Diet, meeting in Pressburg/Pozsony in February 1452, sent a group to Vienna. On March 5, the Austrian and Hungarian nobles together asked Frederick III to give up his guardianship of their young king. Frederick, who had become Holy Roman Emperor, first refused. Hunyadi called a Diet to discuss the situation. But before the Diet made any decision, the combined armies of the Austrian and Bohemian nobles forced the Emperor to hand over the young king to Count Ulrich of Celje on September 4. Meanwhile, Hunyadi had met Jiskra in Körmöcbánya (today's Kremnica, Slovakia) and they made a treaty on August 24. In September, Hunyadi sent messengers to Constantinople and promised military help to the Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI. In return, he asked for two Byzantine forts on the Black Sea, Silivri and Misivri, but the Emperor refused.

Hunyadi called a Diet to Buda, but the nobles and church leaders preferred to visit Ladislaus V in Vienna in November. At the Diet of Vienna, Hunyadi gave up his role as regent. However, the King appointed him "captain general of the kingdom" on January 30, 1453. The King even allowed Hunyadi to keep the royal castles and royal income he had at that time. Hunyadi also received Beszterce (today's Bistrița, Romania), a region of the Transylvanian Saxons, with the title "perpetual count" from Ladislaus V. This was the first time a hereditary title was given in the Kingdom of Hungary.

Later Years and Final Victory

Conflicts and Agreements (1453–1455)

In a letter from April 28, 1453, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, who later became Pope Pius II, wrote that King Ladislaus V's lands were ruled by "three men": Hungary by Hunyadi, Bohemia by George of Poděbrady, and Austria by Ulrich of Celje. However, Hunyadi's power slowly weakened. Even many of his former friends started to suspect his actions to keep his power. The people of Beszterce forced him to sign a document confirming their old freedoms on July 22. Hunyadi's long-time friend, Nicholas Újlaki, made a formal alliance with Palatine Ladislaus Garai and Judge royal Ladislaus Pálóci in September. They declared their intention to bring back full royal authority.

Hunyadi went with the young King to Prague and made a treaty with Ulrich Eizinger (who had driven Ulrich of Celje out of Austria) and George of Poděbrady at the end of the year. After returning to Hungary, Hunyadi called a Diet in the King's name, but without his permission. This was to prepare for a war against the Ottomans, who had captured Constantinople in May 1453. The Diet ordered the army to get ready, and Hunyadi's position as supreme commander was confirmed for a year. However, many of these decisions were never carried out. For example, the Diet ordered all landowners to provide soldiers based on the number of peasant households on their lands, but this law was never put into practice.

Ladislaus V called a new Diet that met in March or April. At this Diet, his messengers, three Austrian nobles, announced that the King planned to manage royal income through officials chosen by the Diet. He also wanted to set up two councils (also with members chosen by the nobles) to help him rule the country. However, the Diet refused to approve most of the King's ideas. Only the creation of a royal council with six church leaders, six nobles, and six common nobles was accepted. Hunyadi, who knew the King was trying to limit his power, demanded an explanation. But the King denied knowing about his representatives' actions. On the other hand, Jiskra returned to Hungary at Ladislaus V's request, and the King put him in charge of the mining towns. In response, Hunyadi convinced Ulrich of Celje to give him several royal forts (and their lands) that had been given as security in Trencsén County.

The Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed II, invaded Serbia in May 1454 and surrounded Smederevo. This broke the truce of November 1451 between his empire and Hungary. Hunyadi decided to act and began gathering his armies at Belgrade, forcing the Sultan to lift the siege and leave Serbia in August. However, an Ottoman force of 32,000 soldiers continued to raid Serbia until Hunyadi defeated them at Kruševac on September 29. He then led a raid into the Ottoman Empire and destroyed Vidin before returning to Belgrade.

Emperor Frederick III called a meeting of the Imperial Diet in Wiener Neustadt to discuss a new crusade against the Ottomans. Messengers from the Hungarian, Polish, Aragonese, and Burgundian rulers were there. No final decisions were made because the Emperor did not want a sudden attack against the Ottomans. The new Pope, Callixtus III, was a strong supporter of the crusade.

King Ladislaus V visited Buda in February 1456. Ulrich of Celje, who came with the King to Buda, confirmed his alliance with Ladislaus Garai and Nicholas Újlaki. These three nobles turned against Hunyadi and accused him of misusing his power. A new Ottoman invasion against Serbia led to a new agreement between Hunyadi and his opponents. Hunyadi gave up control of some royal income and three royal forts, including Buda. On the other hand, Hunyadi, Garai, and Újlaki agreed that they would stop the King from hiring foreigners in the royal government in June 1455. Hunyadi and Count Ulrich also made peace the next month. At that time, Hunyadi's younger son, Matthias, and the Count's daughter, Elizabeth, became engaged.

The Belgrade Victory and Hunyadi's Death (1455–1456)

Messengers from Ragusa (Dubrovnik, Croatia) were the first to tell the Hungarian leaders that Mehmed II was preparing to invade Hungary. In a letter to Hunyadi, whom he called "the Maccabeus of our time," the Pope's representative, Cardinal Juan Carvajal, made it clear that there was little chance of help from other countries against the Ottomans. With Ottoman support, Vladislav II of Wallachia even raided the southern parts of Transylvania in late 1455.

John of Capistrano, a Franciscan friar and church official, began preaching about an anti-Ottoman crusade in Hungary in February 1456. The Diet ordered the army to mobilize in April, but most nobles did not obey. They continued to fight their local enemies, including the Hussites in Upper Hungary. Before leaving Transylvania to fight the Ottomans, Hunyadi had to deal with a rebellion by the Vlachs in Fogaras County. He also helped Vlad Dracula, a son of the late Vlad Dracul, take the Wallachian throne from Vladislav II.

King Ladislaus V left Hungary for Vienna in May. Hunyadi hired 5,000 Hungarian, Czech, and Polish hired soldiers and sent them to Belgrade. Belgrade was a very important fortress for defending Hungary's southern borders. The Ottoman forces marched through Serbia and approached Nándorfehérvár (modern-day Belgrade) in June. A crusade army, mostly made up of farmers from nearby counties, who had been inspired by John of Capistrano's speeches, also began to gather at the fortress in early July. The Ottoman siege of Belgrade, led personally by Sultan Mehmed II, began with the bombing of the walls on July 4.

Hunyadi quickly formed a relief army and gathered a fleet of 200 ships on the Danube. Hunyadi's ships destroyed the Ottoman fleet on July 14. This victory stopped the Ottomans from completely blocking the fortress, allowing Hunyadi and his troops to enter. The Ottomans launched a major attack on July 21. With the help of crusaders who kept arriving, Hunyadi fought off the fierce Ottoman attacks and broke into their camp on July 22. Although wounded, Sultan Mehmed II decided to keep fighting. But a riot in his camp forced him to lift the siege and retreat from Belgrade during the night.

The crusaders' victory over the Sultan, who had conquered Constantinople, created excitement across Europe. Celebrations for Hunyadi's triumph were held in Venice and Oxford. However, unrest grew in the crusaders' camp because the farmers felt the nobles had not played a big role in the victory. To avoid a rebellion, Hunyadi and Capistrano disbanded the crusaders' army.

Meanwhile, a plague broke out and killed many people in the crusaders' camp. Hunyadi also became ill and died near Zimony (today's Zemun, Serbia) on August 11. He was buried in the Roman Catholic St. Michael's Cathedral in Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia).

[Hunyadi] ruled the country with a firm hand, and while the king was away, he was seen as his equal. After defeating the Turks at Belgrade [...], he lived only a short time before dying of disease. When he was sick, they say he did not allow the Body of Our Lord to be brought to him. He said it was not right for a king to enter the house of a servant. Even though he was weak, he ordered himself to be carried to church. There, he made his confession in a Christian way, received the holy Eucharist, and gave his soul to God in the arms of the priests. He was a lucky soul to have reached Heaven as both a messenger and the doer of the heroic act at Belgrade.

Family Life

In 1432, Hunyadi married Erzsébet Szilágyi (c. 1410–1483), a Hungarian noblewoman. John Hunyadi had two children: Ladislaus and Matthias Corvinus. Ladislaus was later executed by order of King Ladislaus V after a conflict with Ulrich II of Celje. Matthias was elected king on January 20, 1458, after Ladislaus V's death. This was the first time in Hungarian history that a nobleman, without royal family ties, became king.

Hunyadi's Lasting Impact

The Noon Bell Tradition

Pope Callixtus III ordered church bells across Europe to ring every day at noon. This was a call for believers to pray for the Christian defenders of Belgrade. This tradition of the noon bell is still linked to the Belgrade victory and Pope Callixtus III's order. It continues even in Protestant and Orthodox churches. In the history of Oxford University, the victory was celebrated with bells and great festivities in England. Hunyadi sent a special messenger, Erasmus Fullar, to Oxford with the news of the victory.

A National Hero

Along with his son Matthias Corvinus, John Hunyadi is seen as a Hungarian national hero. He is praised as a great defender against the Ottoman threat.

Romanian history also recognizes Hunyadi and gives him an important place. Pope Pius II wrote that "Hunyadi did not increase so much the glory of the Hungarians, but especially the glory of the Romanians among whom he was born."

The French writer and diplomat Philippe de Commines described Hunyadi as "a very brave gentleman, called the White Knight of Wallachia. He was a person of great honor and wisdom, who had ruled the kingdom of Hungary for a long time and won several battles against the Turks."

Pietro Ranzano wrote in his work Annales omnium temporum (1490–1492) that John Hunyadi was commonly called "Ianco." In writings by Byzantine Greek authors, he is called names like "Ianco" or "Iancou."

Byzantine literature even treated Hunyadi as a saint:

First, I praise the Emperor of Hellas

who was Alexander the Macedon, the son of Olympias.

The Christian Emperor, who is the peak and the root

and found the cross, the mighty Constantine.

and the third one is the absolutely marvelous Emperor John.

How can I write enough praise for him

and how can my mind rise to such high praise?

Because like the two Emperors mentioned above

I also show such respect to the above Emperor.

It is right and proper that the Church of Rome

and all Christians from East and West

respectfully remember him fully.

He became famous in the battles of wars

the brave and the timid ones and all people, I say,

should bow before John of Hungary today,

praise him as a knight

praise him today as an Emperor,

together with the ancient, mighty, and brave Samson,

with the terrible Alexander and the mighty Constantine.

I praise the evangelists, I also praise the prophets,

and the mighty Saints fighting for Christ,

and among them, I praise Emperor John.

Hunyadi was "recognized as being Hungarian" and "often called Ugrin Janko, 'Janko the Hungarian'" in Serbian and Croatian societies of the 1400s. In Bulgarian folklore, Hunyadi is remembered as the epic hero Yankul(a) Voivoda.

He was a role model for the fictional character of Tirant lo Blanc, a famous romance written by Joanot Martorell in 1490. Both characters had a raven on their shield.

Nicolaus Olahus was John Hunyadi's nephew.

In 1515, the English printer Wynkyn de Worde published a long poem called 'Capystranus', which described the defeat of the Turks.

In 1791, Hannah Brand wrote a play called 'Huniades or The Siege of Belgrade', which was very popular in Norwich, England.

The Iancu de Hunedoara National College in Hunedoara, Romania, is named after him.

Images for kids

-

Statue of John Hunyadi in the Royal Castle in Budapest, Hungary (made by István Tóth in 1903)

-

Statutes of Julian Cesarini, John Hunyadi and John of Capistrano in Szeged, Hungary (made by Ferenc Sidló in 1930)

-

Relief of John Hunyadi on the pedestal of the statue of Matthias Corvinus in Szeged, Hungary (made by Gábor Józsa in 2001)

See also

In Spanish: Juan Hunyadi para niños

In Spanish: Juan Hunyadi para niños