Skanderbeg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Skanderbeg |

|

|---|---|

| Lord of Albania Latin: Dominus Albaniae |

|

Portrait of Skanderbeg painted by Cristofano dell'Altissimo

|

|

| Reign | 28 November 1443 – 17 January 1468 |

| Predecessor | Gjon Kastrioti |

| Successor | Gjon Kastrioti II |

| Born | Gjergj (see Name) 6 May 1405 Principality of Kastrioti |

| Died | 17 January 1468 (aged 62) Alessio, Republic of Venice |

| Burial | Church of Saint Nicholas, Lezhë |

| Spouse | Donika Arianiti |

| Issue | Gjon Kastrioti II |

| House | Kastrioti |

| Father | Gjon Kastrioti |

| Mother | Voisava Kastrioti |

| Religion | Islam (1423–1443) Catholicism (1443–1468) |

| Occupation | Lord of the Principality of Kastrioti, Chief military commander of League of Lezhë |

| Signature | |

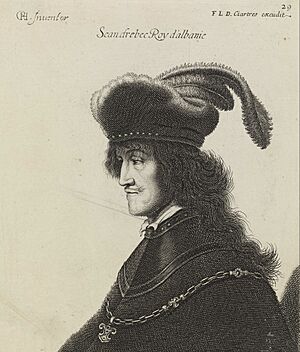

Gjergj Kastrioti (1405 – 17 January 1468), known as Skanderbeg, was an Albanian leader and military commander. He led a big rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in the area that is now Albania and nearby countries.

Skanderbeg came from the noble Kastrioti family. When he was young, he was sent to the Ottoman court as a hostage. There, he was educated and served the Ottoman Sultan for twenty years. He became a high-ranking officer, even a governor, by 1440.

In 1443, during a battle, he left the Ottoman army. He then became the ruler of Krujë and the surrounding areas in central Albania. In 1444, with support from other Albanian nobles and the Church, he formed a union called the League of Lezhë. This was the first time many Albanian areas were united under one leader.

Skanderbeg was a brilliant military leader. For 25 years, from 1443 to 1468, his army of 10,000 men fought against much larger Ottoman forces. He won many battles, becoming a symbol of Christian resistance against the Ottomans in Europe. He always called himself "Lord of Albania."

In 1451, he made a deal with the Kingdom of Naples for protection. He helped the King of Naples in his wars in Italy in 1460–61. Skanderbeg fought the Ottomans with the Venetians until he died in 1468. He is remembered as a great opponent of the Ottoman Empire. He became a very important figure in the Albanian National Awakening in the 1800s. Today, he is honored in Albania with many monuments and cultural works.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Skanderbeg's first name in Albanian is Gjergj, which means George. In Italian, it was written as Giorgio. On his official seal, he signed as Georgius Castriotus Scanderbego.

The Ottoman Turks gave him the name İskender bey. This means "Lord Alexander" or "Leader Alexander." The name Skënderbeu or Skënderbej is the Albanian version. Many believe this name compared his military skills to those of Alexander the Great. Skanderbeg himself used this name even after he became Christian again. His family in Italy later became known as the Castriota-Scanderbeg.

Skanderbeg's Appearance and Spirit

People described Skanderbeg as tall and thin, with a strong chest and wide shoulders. He had black hair, fiery eyes, and a powerful voice.

He was trained as a soldier from a young age. This training made him even stronger. Stories say he would train hard on mountains, even sleeping in the snow in winter. In summer, he would keep training to become an "invincible fighter."

Legends say he was so strong that he could cut a man or an animal in half with one sword swing. One story tells how he once cut off an opponent's head in a duel and showed it to the Sultan, earning the Sultan's favor.

Early Life and Hostage Years

Skanderbeg was born in 1405. His father, Gjon Kastrioti, ruled a territory in north-central Albania. His mother was Voisava Kastrioti. Skanderbeg had three older brothers and five sisters.

His father, Gjon Kastrioti, sometimes changed alliances and religions to protect his lands. He became a vassal of the Ottoman Sultan and had to pay tribute and provide soldiers. In 1409, Gjon sent his oldest son, Stanisha, as a hostage to the Sultan.

Skanderbeg and one of his brothers were also taken as hostages by the Sultan. They were enrolled in the Devşirme system. This system took Christian boys, converted them to Islam, and trained them to be military officers. However, some historians believe Skanderbeg was sent as a hostage when he was 18, not as a young boy for the Devşirme. Hostages were not treated badly. They often went to the best military schools to become future leaders.

Serving the Ottomans: 1423 to 1443

Skanderbeg was sent to the Ottoman court in 1415 and again in 1423. He received military training at the Enderun School.

The first record of Skanderbeg's name is from 1426. His father and four sons donated money from two villages to a Serbian monastery. Later, his father and sons bought rights to live at the monastery.

After finishing school, the Sultan gave Skanderbeg control over some land near his father's territory. His father worried that Skanderbeg might be ordered to take his land. Skanderbeg fought for the Sultan in different campaigns and became a sipahi (a cavalry soldier).

Even when other Albanians revolted in 1432–1436, Skanderbeg remained loyal to the Sultan. In 1437–38, he became a governor of Krujë. He controlled a large area that used to belong to his father. He was called Juvan oglu Iskender bey in Ottoman documents. The Sultan gave him the title of vali (governor) because of his military skills. He led a cavalry unit of 5,000 men.

After his brothers and father died, Skanderbeg kept good relations with the Republic of Ragusa and Venice. From 1438 to 1443, he fought with the Ottomans in Europe, often against Christian forces led by Janos Hunyadi. In 1440, Skanderbeg became the governor of Dibra.

While serving the Ottomans in Albania, he stayed close to the local people and other Albanian noble families.

Skanderbeg's Rise

In early November 1443, Skanderbeg left the Ottoman army during the Battle of Niš. He was fighting against the crusaders of John Hunyadi. Skanderbeg left with 300 other Albanian soldiers.

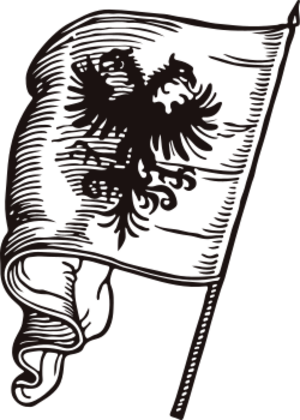

He quickly went to Krujë, arriving on November 28. He used a fake letter from the Sultan to take control of the city that very day. He also captured other nearby castles. He then raised a red flag with a black double-headed eagle over Krujë. This flag is similar to Albania's national flag today.

Skanderbeg stopped being Muslim and became Christian again. He ordered others who had become Muslim to convert to Christianity or leave. The Ottomans then called him "treacherous Iskander."

On March 2, 1444, Skanderbeg called Albanian noblemen to Lezhë. They formed a military alliance called the League of Lezhë. Powerful Albanian families joined, along with a Serbian nobleman.

Skanderbeg created a mobile army. This army used the mountainous land to its advantage, fighting a guerrilla war against the Ottomans. He would attack quickly and then disappear. For the first 8–10 years, Skanderbeg led 10,000–15,000 soldiers. He had to convince other leaders to follow his plans.

In the summer of 1444, Skanderbeg's united Albanian army fought the Ottomans at the Plain of Torvioll. The Ottomans had 25,000 men, while Skanderbeg had 7,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry. Skanderbeg hid 3,000 cavalry behind enemy lines. They attacked, surrounding the Ottomans. Skanderbeg won a great victory, killing about 8,000 Ottomans. This was one of the first times a large Ottoman army was defeated in Europe.

In 1445, Skanderbeg defeated an Ottoman force of 9,000–15,000 men. He lured them into a valley and attacked, killing 1,500 of their men. He won two more times the next year.

-

Skanderbeg's return to Krujë, 1444 (woodcut by Jost Amman)

-

A woodcut of the battle of Varna in 1444

War with Venice: 1447 to 1448

At first, Venice supported Skanderbeg. They saw him as a shield against the Ottomans. But as Skanderbeg grew stronger, Venice saw him as a threat. This led to a war between Albania and Venice in 1447–48. Venice even offered rewards to anyone who would kill Skanderbeg. They also asked the Ottomans to attack Skanderbeg at the same time.

On May 14, 1448, the Ottoman Sultan Murad II and his son Mehmed II besieged the castle of Sfetigrad. The Albanian soldiers inside fought bravely. Skanderbeg attacked the Ottoman forces from outside the castle. On July 23, 1448, Skanderbeg won a battle against a Venetian army near Shkodër.

In late summer 1448, the Albanian soldiers in Sfetigrad surrendered because they ran out of drinking water. Skanderbeg lost the castle, which was important for controlling the eastern plains. At the same time, he besieged Venetian towns like Durazzo (modern Durrës) and Lezhë.

In August 1448, Skanderbeg defeated Mustafa Pasha in Dibër. Mustafa Pasha lost 3,000 men and was captured. Skanderbeg learned that Venice had pushed the Ottomans to invade Albania. Venice then wanted peace.

On July 23, 1448, Skanderbeg crossed the Drin River with 10,000 men. He met a Venetian force of 15,000. Skanderbeg's archers started the battle. After hours of fighting, Venetian troops began to run away. Skanderbeg ordered a full attack, defeating the entire Venetian army. The Albanians killed 2,500 Venetians and captured 1,000. Skanderbeg's army lost 400 men.

A peace treaty was signed on October 4, 1448. Venice kept some land but gave Skanderbeg other areas. Venice also agreed to pay Skanderbeg 1,400 ducats each year. Skanderbeg also made stronger ties with King Alfonso V of Aragon, who was Venice's rival.

Skanderbeg agreed to peace because John Hunyadi's army was advancing in Kosovo. Skanderbeg wanted to join Hunyadi against the Sultan. However, he was stopped by Đurađ Branković, who was allied with the Ottomans. Skanderbeg was angry and raided Serbian villages to punish Branković.

Siege of Krujë (1450)

In June 1450, Sultan Murad II and his son Mehmed II led an army of about 100,000 men to besiege Krujë. Skanderbeg used a "scorched earth" strategy, destroying resources so the Ottomans couldn't use them. He left 1,500 men to defend Krujë under Vrana Konti. Skanderbeg and the rest of his army attacked Ottoman supply lines.

The defenders of Krujë fought off three major Ottoman attacks. The Ottomans tried to cut off the city's water, but they failed. They also tried to dig a tunnel, but it collapsed. Vrana Konti refused an offer of money and a high rank from the Ottomans.

Venetian merchants from nearby cities sold food to both sides. Skanderbeg attacked Venetian caravans, causing tension. But the issue was resolved. By September 1450, the Ottoman camp was in chaos. They hadn't taken the castle, morale was low, and disease was spreading. In October 1450, Murad II gave up the siege and returned to Edirne. The Ottomans lost 20,000 men during the siege. Murad died a few months later in February 1451.

After the siege, Skanderbeg had lost almost everything except Krujë. Other nobles in Albania had allied with Murad II. Skanderbeg went to Ragusa to ask for help. The Pope also helped him financially. Skanderbeg's success was praised across Europe.

Strengthening His Position

Even though Skanderbeg had won, there was famine in Albania. He made a closer alliance with King Alfonso V of Naples. In January 1451, Alfonso made Skanderbeg "captain general of the king of Aragon." They signed the Treaty of Gaeta in March 1451. Skanderbeg became a formal vassal in exchange for military help. Skanderbeg kept full control of his lands. Alfonso promised to respect Krujë's old rights and pay Skanderbeg 1,500 ducats a year. Skanderbeg promised to be loyal to Alfonso after the Ottomans were gone, which never happened in his lifetime.

Skanderbeg married Donika, the daughter of a powerful Albanian nobleman, on April 21, 1451. Their only child was Gjon Kastrioti II.

In 1451, Skanderbeg rebuilt Krujë and built a new fortress in Modrica. This new fortress helped stop Ottoman forces from passing through easily.

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II, now called "the Conqueror," planned to defeat Hungary and move into Italy. In 1452, Mehmed II sent his first army against Skanderbeg. This army had about 25,000 men.

Skanderbeg gathered 14,000 men. He planned to defeat one part of the Ottoman army first, then surround the other. On July 21, he attacked quickly and defeated the Ottomans. This victory surprised everyone, as Mehmed II was even more powerful than his father. Skanderbeg also made peace with the Dukagjini family, another Albanian noble family.

On April 22, 1453, Mehmed sent another army to Albania. Skanderbeg launched a surprise cavalry attack, causing chaos in the Ottoman camp. The Ottoman commander was killed, and Skanderbeg won again. Five weeks later, Mehmed II captured Constantinople.

Skanderbeg kept asking King Alfonso and the Pope for help against possible Ottoman invasions. The Pope sent money, and Alfonso sent soldiers and money. However, Venice was not happy about Skanderbeg's alliance with Naples, their old enemy.

In June 1454, Ramon d'Ortafà came to Krujë as the viceroy of Albania. He brought a flag with a white cross, a symbol of a new Crusade. This Crusade never happened. The Neapolitan troops were used in the Siege of Berat, where most of them were destroyed.

The Siege of Berat was a victory for the Ottomans. Skanderbeg had besieged the castle for months. The Ottoman officer inside promised to surrender. Skanderbeg relaxed his guard and split his forces. This was a mistake. The Ottomans sent a large cavalry force and surprised the Albanian cavalry, killing almost all 5,000 of them. This defeat weakened Skanderbeg's support from other Albanian nobles.

In 1456, Moisi Golemi, one of Skanderbeg's commanders, joined the Ottomans. He returned to Albania with an Ottoman army of 15,000 men. But Skanderbeg defeated him in the Battle of Oranik. Moisi then returned to Skanderbeg, who forgave him.

Also in 1456, Skanderbeg's nephew, George Strez Balšić, sold a fortress to the Ottomans. He was sent to prison in Naples. Skanderbeg's own nephew, Hamza Kastrioti, left to join the Ottomans after Skanderbeg's son, John Castriot II, was born.

In the summer of 1457, a huge Ottoman army of about 70,000 men invaded Albania. This army was led by Isak-Beg and Hamza Kastrioti, who knew Skanderbeg's tactics. After months of avoiding them, Skanderbeg attacked the Ottomans on September 2. He defeated them, killing 15,000 Ottomans and capturing 15,000 more. This was one of Skanderbeg's most famous victories. It led to a five-year peace treaty with Sultan Mehmed II. Hamza was captured and sent to prison in Naples.

After this victory, Skanderbeg's ties with the Pope grew stronger. The Pope, Calixtus III, declared Skanderbeg a "Captain-General" in the war against the Ottomans. The Pope gave him the title Athleta Christi, or Champion of Christ.

On June 27, 1458, King Alfonso V died. Skanderbeg sent messengers to his son, King Ferdinand I. Skanderbeg's relationship with Naples continued, but now Skanderbeg had to help King Ferdinand. In 1459, Skanderbeg captured a fortress from the Ottomans and gave it to Venice to improve relations.

In November 1460, Stefan Branković, a Serbian leader, married Skanderbeg's wife's sister. Skanderbeg gave him land.

Helping Italy: 1460 to 1462

In 1460, King Ferdinand of Naples faced a serious uprising. He asked Skanderbeg for help. Skanderbeg made a three-year peace deal with the Ottomans in April 1461. In late August 1461, he landed in Italy with 1,000 cavalry and 2,000 infantry.

He defeated Ferdinand's enemies and helped secure Ferdinand's throne. Then he returned to Albania. King Ferdinand was very grateful. After Skanderbeg's death, Ferdinand rewarded Skanderbeg's family with land and castles in Italy.

Last Years

After helping Naples, Skanderbeg returned home because Ottoman armies were approaching Albania. He defeated three different Ottoman armies. This forced Sultan Mehmed II to agree to a 10-year peace treaty in April 1463. Skanderbeg didn't want peace, but his nobles convinced him.

Meanwhile, Venice started a war with the Ottomans (1463–79). Venice now saw Skanderbeg as a valuable ally. They renewed their peace treaty with him. In November 1463, Pope Pius II tried to organize a new crusade against the Ottomans. Skanderbeg joined, declaring war on the Ottomans on November 27, 1463. He defeated an Ottoman force near Ohrid. The Pope's plan was for Skanderbeg to lead 20,000 soldiers. But Pope Pius II died in August 1464. Skanderbeg was left to face the Ottomans alone again.

In April 1465, Skanderbeg defeated an Ottoman Albanian governor. However, during the battle, the Ottomans captured important Albanian noblemen. These men were sent to Constantinople and cruelly killed. Skanderbeg's pleas to get them back failed. Later that year, Skanderbeg defeated two more Ottoman armies.

Second Siege of Krujë (1466–67)

In 1466, Sultan Mehmed II personally led an army of 30,000 into Albania. He began the Second Siege of Krujë. The city was defended by 4,400 men. After several months, Mehmed II realized he couldn't capture Krujë by force. He left the siege but left 30,000 men to continue it. He also built a new castle called Il-basan (modern Elbasan) to support the siege.

Skanderbeg spent the winter of 1466–67 in Italy, trying to get money from the Pope. He was so poor he couldn't pay his hotel bill. The Pope eventually gave him some money. Naples was more generous with money and weapons.

When Skanderbeg returned, he allied with Lekë Dukagjini. On April 19, 1467, they defeated Ottoman reinforcements. Four days later, on April 23, they attacked the Ottoman forces besieging Krujë. The Second Siege of Krujë was broken. The Ottoman commander, Ballaban Pasha, was killed.

With Ballaban's death, the Ottoman forces were surrounded. They asked to leave freely. Skanderbeg was ready to agree, but many nobles refused. The Albanians then attacked the surrounded Ottoman army. Skanderbeg entered Krujë on April 23, 1467. This victory was celebrated, and more young warriors joined Skanderbeg's army.

After these events, Skanderbeg's forces tried to besiege Elbasan but failed.

The destruction of Ballaban Pasha's army forced Mehmed II to march against Skanderbeg again in the summer of 1467. Skanderbeg retreated to the mountains. The Ottomans failed to take Krujë again, but they caused immense destruction.

The war caused many deaths among civilians and ruined the country's economy. Because of these problems, Skanderbeg called all the Albanian noblemen to a meeting in Lezhë in January 1468. They planned a new war strategy. During this meeting, Skanderbeg became ill with malaria and died on January 17, 1468, at age 62.

What Happened Next

In Europe, princes and rulers mourned Skanderbeg's death. King Ferdinand I of Naples promised help to Skanderbeg's family. During Skanderbeg's life, his help to Naples led to Albanian soldiers settling in villages in Southern Italy. After Skanderbeg's death and the Ottoman conquest, many Albanian leaders and people found refuge in Naples. This led to the creation of the Arbëresh community in Southern Italy, which still exists today.

Ivan Strez Balšić was seen as Skanderbeg's successor by Venice. He and other Albanian leaders continued to fight for Venice. Venice allowed Skanderbeg's widow to defend Krujë with Venetian soldiers.

Krujë held out during its fourth siege, which started in 1477. But on June 16, 1478, the city surrendered due to starvation. Sultan Mehmed II had promised them safe passage. However, as the Albanians left, the Ottomans killed the men and enslaved the women and children. In 1479, the Ottomans captured Shkodër. Venice's Albanian lands were reduced to only a few towns.

Skanderbeg's son, John Castriot II, continued to fight the Ottomans from 1481–84. There was also a major revolt in southern Albania in 1492. In 1501, Skanderbeg's grandson, George Castriot II, tried to lead another uprising, but it also failed.

In 1594, there was another attempt to free Albania from the Ottomans. Albanian leaders planned a revolt with the help of the Pope, but the Pope never sent aid.

After Albania fell to the Ottomans, the Kingdom of Naples gave land and noble titles to Skanderbeg's family. His family controlled lands in Italy. His son married a Serbian princess. Two branches of the Kastrioti family still exist today.

-

Mural commemorating a battle of Skanderbeg. The Arms of Skanderbeg visible in the forefront are copies of the originals held at the Art Museum of Vienna.

-

The original Skanderbeg's helmet at the Art Museum of Vienna.

Skanderbeg's Legacy

The Ottoman Empire's expansion slowed down while Skanderbeg's forces resisted. He is often credited with delaying Ottoman expansion into Western Europe. This gave Italian states more time to prepare for the Ottomans. While Albania's resistance was vital, other leaders like Vlad III Dracula and Stephen III the Great also fought bravely.

Skanderbeg is seen as a commanding figure in Albanian history and in 15th-century European history. He was considered a hero even in his own time. Most European nations did not give him enough support. This meant that his victories did not permanently stop the Ottomans from invading the Western Balkans.

In 1481, Sultan Mehmet II captured Otranto and killed the men there. This proved what Skanderbeg had warned about. Skanderbeg's main legacy was the inspiration he gave to those who saw him as a symbol of Christian struggle against the Ottoman Empire.

His fight became very important to the Albanian people. Among the Arbëresh (Italo-Albanians), stories and songs about Skanderbeg kept his memory alive. During the Albanian National Awakening in the late 1800s, Skanderbeg became a central symbol of Albanian nationalism. He represented their connection to Europe and inspired their fight for unity and independence. Today, Muslim Albanians see him as a national defender, not just a Christian hero.

The Ottomans respected Skanderbeg so much that when they found his grave, they opened it. They made amulets from his bones, believing they would gain bravery from them. Stories say Skanderbeg killed three thousand Ottomans with his own hand. He was also said to be able to cut two men in half with one sword stroke.

In 2005, the United States Congress honored Skanderbeg for his role in saving Western Europe from Ottoman rule.

-

Skanderbeg's mausoleum (former Selimie Mosque and St. Nicolas' Church) in Lezhë

-

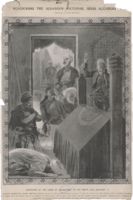

Honoring the Albanian National Hero, Scanderbeg. Albanians at the Tomb of Scanderbeg on His Death Day. Drawn by R. Caton Woodville, 17 January 1908.

-

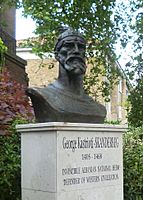

A bust of Skanderbeg on Inverness Terrace, Paddington, London where there is a sizeable Albanian community. The bust was unveiled in 2012 on the 100th anniversary of Albanian independence

Skanderbeg in Books and Art

Two important books about Skanderbeg were written in the 1400s. One was a short biography by Serbian writer Martin Segon. The other was Memoirs of a Janissary by Konstantin Mihailović, a Serb who was a soldier in the Ottoman army.

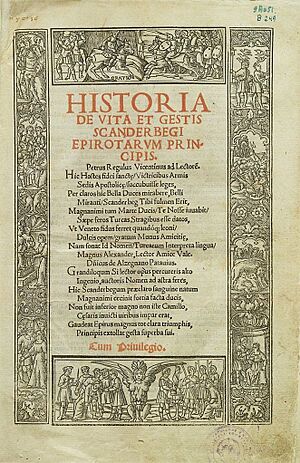

Skanderbeg became very famous in Western Europe after his death. In the 1500s and 1600s, many books about him appeared. One of the earliest was History of the life and deeds of Scanderbeg, Prince of the Epirotes (1508) by Albanian-Venetian historian Marinus Barletius. Barleti's book was very popular.

Franciscus Blancus, an Albanian Catholic bishop, also wrote a biography of Skanderbeg in 1636. French philosopher Voltaire greatly admired Skanderbeg. Many other writers and historians praised him as a great general and leader.

The Italian composer Antonio Vivaldi wrote an opera called Scanderbeg in 1718. Another opera was composed by French composer François Francœur in 1735. In the 1900s, Albanian composer Prenkë Jakova wrote a third opera about Skanderbeg.

Skanderbeg is the main character in three British plays from the 1700s. Poets like Ronsard and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow also wrote poems about him. The historian Edward Gibbon greatly admired Skanderbeg.

The Great Warrior Skanderbeg, a 1953 Albanian-Soviet film, won an award at the 1954 Cannes Film Festival.

Skanderbeg's memory is honored in many museums, like the Skanderbeg Museum in Krujë Castle. Many monuments are dedicated to him in Albanian cities like Tirana, Krujë, and Peshkopi. A palace in Rome where Skanderbeg stayed is still called Palazzo Skanderbeg. Statues of Skanderbeg can also be found in cities like Skopje, Pristina, Geneva, Brussels, and London. In 2006, the first statue of Skanderbeg in the United States was unveiled in Michigan.

His name is also used for the Skanderbeg Military University in Tirana, a football stadium, and the Order of Skanderbeg.

See also

In Spanish: Skanderbeg para niños

In Spanish: Skanderbeg para niños

- Arms of Skanderbeg

- Myth of Skanderbeg

- Timeline of Skanderbeg

- Year of Skanderbeg