Voivode of Transylvania facts for kids

The Voivode of Transylvania was a very important official in Transylvania when it was part of the Kingdom of Hungary. This role existed from the 12th to the 16th century. The king chose the voivode. The voivode was also the head, or ispán, of Fehér County. They were in charge of the ispáns (leaders) of all the other counties in Transylvania.

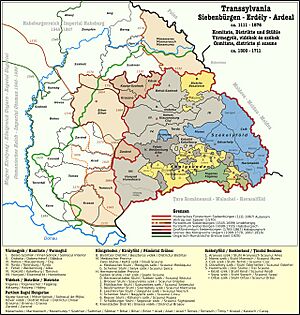

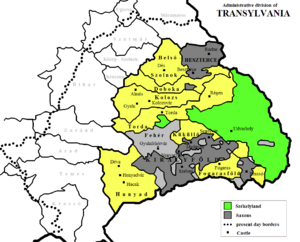

Voivodes had many powers. They managed the government, led the military, and made legal decisions. However, they did not control all of Transylvania. The Saxon and Székely people had their own special districts called "seats" from the 13th century. These areas were not under the voivode's control. Over time, kings also made some towns and villages free from the voivode's power. Even so, the Voivodeship of Transylvania was the biggest single area managed by one official in the whole kingdom during the 15th century.

Voivodes earned money from royal lands linked to their job. But only the kings could give out land, collect taxes, charge tolls, or make money. While some voivodes, like Roland Borsa and Ladislaus Kán, fought against the king, most of them stayed loyal royal officials.

In the 16th century, the Kingdom of Hungary started to fall apart. The last voivodes of Transylvania, from the Báthory family, stopped being just high-ranking officials. They became the actual heads of state for a new principality that formed in the eastern parts of the kingdom. This new principality was under the control of the Ottoman Empire. So, Stephen Báthory, who was chosen as voivode by the Diet (assembly) of this new land, officially changed his title to prince in 1576 when he became King of Poland.

Contents

What Was the Voivode?

The exact start of the voivode's job is not clear. The word "voivode" comes from a Slavic language and means "commander" or "lieutenant." Some historians believe the title shows that local ruling traditions continued from the Slavic people who lived there before.

Transylvania was a border region, far from the king's direct control. This is why the voivodeship was created. The voivodes were never fully independent. They always remained officials who worked for the king. From 1201, voivodes were also the heads of Fehér County. This might mean their job started from the ispán (leader) of that county.

The first person clearly called a voivode in a document was Legforus in 1199. Other old documents sometimes used different titles for the same job, like banus or dux. This shows that the name for the job was not set until the late 13th century.

What Did Voivodes Do?

Areas They Controlled

The areas under the voivodes' power were called the Voivodeship of Transylvania. Voivodes were the main leaders of the ispáns (county heads) in Transylvania. Counties in Transylvania were first mentioned in the 1170s. But older records and discoveries suggest that a county system existed even earlier, in the 11th century.

By the early 13th century, the ispáns of most Transylvanian counties (like Doboka, Hunyad, Kolozs, Küküllő, and Torda) were no longer directly connected to the king. Instead, the voivode hired and fired them. Only the heads of Szolnok County stayed directly linked to the king for longer, until their job joined the voivodeship in the 1260s. Voivodes also served as the ispáns of nearby Arad County between 1321 and 1412.

The kings sometimes freed certain communities from the voivodes' control. For example, a royal document from 1224, called the Diploma Andreanum, put the Saxon lands under the Count of Hermannstadt. This count was chosen by the king and reported directly to him. Similarly, a special royal official, the Count of the Székelys, managed the Székely people from around 1228. Later, in 1462, it became a tradition that every voivode was also appointed Count of the Székelys.

After the Mongol invasion in 1241 and 1242, King Béla IV of Hungary gave special freedom to people in several villages. King Charles I of Hungary also granted freedom to some Saxon communities in 1315.

Voivodes' Income and Property

Being a voivode was one of the most important royal jobs. All the money from lands connected to the royal castles in Transylvania went to the voivodes. They also earned money from fines. However, royal income from taxes, tolls, and mines still belonged to the kings.

For most of the 14th century, voivodes controlled several castles and their lands, including places like Bánffyhunyad and Déva. They also received money from royal estates in Transylvania, such as those at Bonchida and Vajdahunyad. But after 1387, kings started giving these castles and estates to noblemen, bishops, or the Saxon community. By the 1450s, Küküllővár was the last piece of land still connected to the voivode's job.

People living in Transylvanian counties had to provide lodging for the voivodes and their officials. Some privileged settlers were freed from this duty in 1206. In other places, this duty was limited to twice a year. Finally, in 1324, King Charles I freed all Transylvanian noblemen and their workers from this annoying duty.

Voivodes often stayed at the royal court and did not live in Transylvania. Instead, their deputies represented them. The first record of a voivode's helper is from 1221. Later, the title "vice-voivode" became common. Besides vice-voivodes and county ispáns, voivodes also appointed the commanders of royal fortresses. They usually chose noblemen who worked for them, ensuring their followers got a share of the income. When a king fired a voivode, his men were also replaced by the new voivode's men.

Legal Responsibilities

The voivode was one of the highest judges in the kingdom, along with the palatine and the judge royal. They could issue official documents. The oldest one still existing is from 1248. Voivodes or their vice-voivodes always heard legal cases with local noblemen who knew the local rules. At first, they held courts in Marosszentimre. But from the 14th century, they held courts at their own homes. After the 1340s, voivodes rarely led their courts themselves; their deputies usually did.

In 1342, voivode Thomas Szécsényi allowed Transylvanian noblemen to judge cases for peasants on their lands. This was for most cases, but not serious crimes like robbery or violent trespassing. King Louis I of Hungary confirmed this in 1365. Also, kings gave more and more nobles the right to order capital punishment during the same century.

By tradition, noblemen could not be sued outside Transylvania until the 15th century. King Louis I even stopped church leaders and nobles with land in Transylvania from taking minor land disputes to the royal court. However, legal cases between Transylvanians and people from other parts of the kingdom were not handled by the voivodes. People could appeal a voivode's decision to the royal court from the 14th century. But from 1444, appeals against voivodes' decisions had to go to the judge royal.

"General assemblies" became important courts in the late 13th century. These meetings for Transylvanian county representatives were led by the voivode or vice-voivode. The first one was on June 8, 1288. They became very important legal meetings from 1322 and were held regularly, at least once a year.

With the king's permission, voivodes sometimes invited representatives from the Saxon and Székely communities to these general meetings. This helped build legal connections among the future "Three Nations of Transylvania" (Hungarians, Saxons, and Székelys). The threat of the peasants' revolt of 1437 led to the first joint meeting of Hungarian noblemen, Saxons, and Székelys. This meeting was called by the vice-voivode without the king's direct order. Romanian cneazes (leaders) were invited to the general assembly only once, in 1355. Otherwise, the vice-voivodes held separate meetings for them.

Military Responsibilities

The word "voivode" means "commander," which shows they had important military duties. They were the top leaders of the soldiers gathered in the counties they controlled. Even though noblemen had to fight in the king's army, Transylvanian nobles fought under the voivode's command. Voivodes also had their own private group of armed noblemen. Their right to raise an army under their own flag was confirmed by law in 1498.

For example, Pousa, son of Sólyom, who was voivode during the Mongol invasion, died fighting on March 31, 1241. Voivode Lawrence fought in the royal army against Austria in 1246. A Mongol army attacking southern Transylvania was defeated by voivode Ernye in 1260. Roland Borsa fought against the invading Mongols in 1285.

Voivode Nicholas Csáki could not stop an Ottoman invasion of Transylvania in 1420. But John Hunyadi, who was voivode from 1441 to 1446, defeated a large Ottoman army in 1442. His successor, Stephen Báthory, also won a big victory at Breadfield on October 13, 1479. However, John Zápolya (Szapolyai), the last voivode before the battle of Mohács on August 29, 1526, did not arrive at the battle in time. The battle ended with the Ottomans destroying the royal army, and King Louis II of Hungary was killed.

Kings and Their Voivodes

How Voivodes Were Chosen and Removed

Voivodes had a lot of power. Because of this, kings often replaced them. Forty-three different voivodes ruled between 1199 and 1288. Kings usually avoided appointing noblemen who owned land in Transylvania as voivodes. Michael was the first voivode to receive land in the province around 1210. However, these lands were taken back in 1228.

After 1288, voivodes stayed in office for longer periods. Roland Borsa served for 10 years, and his successor, Ladislaus Kán, for 20 years. This happened because the central government was weaker under the last two kings of the Árpád dynasty. King Charles I (1308–1342) brought back royal power by defeating rebellious noblemen.

In Transylvania, Thomas Szécsényi, voivode from 1321 to 1342, helped him. Historian Ioan-Aurel Pop describes the time after this as having "voidvodal dynasties." Five members of the Lackfi family (a father and four sons) were appointed one after another between 1356 and 1376. Similarly, Nicholas Csáki (1415–1426) was followed by his son Ladislaus. These voivodes often sent their vice-voivode, Roland Lépes, to represent them instead of visiting Transylvania themselves. From the mid-15th century, it was common for two or even three noblemen to hold the office at the same time. For example, King Wladislas I appointed John Hunyadi and Nicholas Újlaki together in 1441.

Working Together and Conflicts

The Mongols severely damaged the eastern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary, including Transylvania, during their invasion in 1241 and their retreat in 1242. Voivode Lawrence, who held the office for 10 years from 1242, focused on rebuilding the province. One of his successors, Ernye, was dismissed in 1260 by the king's son, Stephen, who had just become Duke of Transylvania. This showed growing tension between the king and his son.

The early years of King Ladislaus IV's rule were marked by fights among powerful noble families. Roland Borsa, voivode in 1282 and from 1284 to 1294, at first helped the king. But then he caused problems himself. He stopped church officials from collecting their income in 1289. He also illegally forced noblemen and Saxon landowners to provide lodging for him and his men. Later, Borsa fought the bishop of Várad and even resisted King Andrew III, who besieged him in a fortress for three months in 1294.

Borsa's successor, Ladislaus Kán, went even further. During his time as voivode from 1294 to 1315, he took over royal powers. He called himself count of Bistritz, Hermannstadt, and the Székelys to control areas that were supposed to be free from voivodal power. He set up his own tax collection system for the whole province. He even captured Otto of Bavaria, who wanted to be king of Hungary, and took the Holy Crown of Hungary from him in 1307. He gave the crown to King Charles I in 1310, but he continued to rule Transylvania almost independently until he died in 1315. His son, also named Ladislaus, declared himself voivode. King Charles I had to appoint Dózsa Debreceni as voivode in 1318. Debreceni defeated some rebellious lords, but royal power in Transylvania was fully restored only by Thomas Szécsényi in the 1320s.

The next rebellion against royal power in Transylvania happened in 1467. Representatives of the Three Nations were angry about a new tax from King Matthias Corvinus. They formed an alliance against the king and chose the three current voivodes as their leaders. The king quickly stopped the revolt, but he did not punish the voivodes because their active role in the revolt was never proven.

How the Office Ended

After King Louis II died in the battle of Mohács in 1526, the nobles could not agree on a new king. First, the voivode, John Szapolyai, was declared king by one group of nobles. But another group chose Ferdinand I of the Habsburg family as their king by the end of the year.

King John I accepted the Ottoman Empire's rule in 1529. But in the Treaty of Nagyvárad of 1538, he agreed that the Habsburgs would become kings after he died. At this point, his voivodes, Stephen Majláth and Emeric Balassa, decided to separate Transylvania from the kingdom. They wanted to save the province from an Ottoman invasion. Other leading Transylvanian noblemen joined them, but King John I stopped their rebellion in a few weeks.

After John's death, Ottoman troops took over the central parts of Hungary in 1541. Sultan Suleiman I allowed the king's widow, Queen Isabella, to keep the lands east of the Tisza river, including Transylvania. She ruled in the name of her baby son, John Sigismund. George Martinuzzi, a bishop, soon started to reorganize the government for the queen and her son. The Ottomans helped the bishop by capturing Stephen Majláth, even though the sultan had earlier confirmed Majláth as voivode. An assembly of the Three Nations chose George Martinuzzi as governor for the young king in 1542.

The job of voivode was empty until September 1549. Then, Ferdinand (who still wanted to reunite the kingdom) appointed Martinuzzi to this position. However, Isabella and her son only left their realm in 1551. After that, Transylvania was again ruled by voivodes chosen by the king, ending with István Dobó. He managed the province until 1556, when Isabella and John Sigismund returned.

John Sigismund stopped calling himself king of Hungary after the Treaty of Speyer in 1570. He then used the title "Prince of Transylvania." His successor, Stephen Báthory, who was chosen by the assembly of the Three Nations, first used the title of voivode for himself. But when he became king of Poland in 1576, he adopted the title "prince of Transylvania." At the same time, he gave the title voivode to his brother Christopher in 1576. Christopher Báthory was followed in 1581 by his young son Sigismund. Sigismund continued to call himself voivode until his uncle Stephen Báthory died in 1586. Sigismund Báthory's title of prince was officially recognized in 1595 by Emperor Rudolph (who was also king of Hungary).

List of Voivodes

12th Century

| Term | Person in Office | King | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1111–c. 1113 | Mercurius | Coloman | Called "prince of Transylvania," but might have just been an important landowner. | |

| 1176–c. 1196 | Leustach of the Rátót clan | Béla III | First voivode mentioned in a royal document (from 1230). He led Hungarian soldiers to help the Byzantine Empire. | |

| 1199–1200 | Legforus | Emeric | His title as voivode is in the earliest royal document (from 1199). | |

| 1200 | Eth of the Geregye clan | Emeric | Also the ispán of Fehér County. |

13th Century

| Term | Person in Office | King | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1201 | Julius of the Kán clan | Emeric | First time in office; also ispán of Fehér County. | |

| 1201 | Nicholas (I) | Emeric | ||

| 1202–1206 | Benedict, son of Korlát | Emeric, Ladislaus III, Andrew II | First time in office. | |

| 1206 | Smaragd of the Smaragd clan | Andrew II | ||

| 1208–1209 | Benedict, son of Korlát | Andrew II | Second time in office; plotted against the king and was sent away. | |

| 1209–1212 | Michael of the Kacsics clan | Andrew II | First voivode to receive land in Transylvania. | |

| 1212–1213 | Berthold of Merania | Andrew II | Brother of Queen Gertrud, King Andrew II's wife; also an archbishop. | |

| 1213 | Nicholas (II) | Andrew II | ||

| 1214 | Julius of the Kán clan | Andrew II | Second time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1214). | |

| 1215 | Simon of the Kacsics clan | Andrew II | ||

| 1216–1217 | Ipoch of the Bogátradvány clan | Andrew II | ||

| 1217 | Raphael | Andrew II | ||

| 1219–1221 | Neuka | Andrew II | ||

| 1221–1222 | Paul, son of Peter | Andrew II | ||

| 1227 | Pousa, son of Sólyom | Andrew II | First time in office. | |

| 1229–1231 | Julius of the Rátót clan | Andrew II | ||

| 1233–1234 | Denis of the Türje clan | Andrew II | ||

| 1235 | Andrew, son of Serafin | Béla IV | Also ispán of Pozsony County (1235). | |

| 1235–1241 | Pousa, son of Sólyom | Béla IV | Second time in office; died fighting the invading Mongols. | |

| 1242–1252 | Lawrence | Béla IV | Also ispán of Valkó County. | |

| b. 1261 | Ernye of the Ákos clan | Béla IV | Called "former ban of Transylvania" in 1261. | |

| 1261 | Csák of the Hahót clan | Béla IV | Also ispán of Szolnok County (1261); the king's son, Stephen, was Duke of Transylvania. | |

| 1263–1264 | Ladislaus (II) of the Kán clan | Béla IV | First time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1263–1264); the king's son, Stephen, was Duke of Transylvania. | |

| 1267–1268 | Nicholas of the Geregye clan | Béla IV | First time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1267–1268); likely held the position continuously from 1264 to 1270; the king's son, Stephen, was Duke of Transylvania. | |

| 1270–1272 | Matthew of the Csák clan | Stephen V | First time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1270–1272). | |

| 1272–1273 | Nicholas of the Geregye clan | Ladislaus IV | Second time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1272–1273). | |

| 1273 | John | Ladislaus IV | Also ispán of Szolnok County (1273). | |

| 1273–1274 | Nicholas of the Geregye clan | Ladislaus IV | Third time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1273–1274). | |

| 1274 | Matthew of the Csák clan | Ladislaus IV | Second time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1274). | |

| 1274 | Nicholas of the Geregye clan | Ladislaus IV | Fourth time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1274). | |

| 1274–1275 | Matthew of the Csák clan | Ladislaus IV | Third time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1274–1275). | |

| 1275 | Ugrin of the Csák clan | Ladislaus IV | First time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1275). | |

| 1275–1276 | Ladislaus (II) of the Kán clan | Ladislaus IV | Second time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1275–1276). | |

| 1276 | Ugrin of the Csák clan | Ladislaus IV | Second time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1276). | |

| 1276 | Matthew of the Csák clan | Ladislaus IV | Fourth time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1276). | |

| 1277 | Nicholas of the Pok clan (Meggyesi) | Ladislaus IV | First time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1277). | |

| 1278–1280 | Finta of the Aba clan | Ladislaus IV | Also ispán of Szolnok County (1278–1280); captured the king. | |

| 1280 | Stephen, son of Tekesh | Ladislaus IV | Also ispán of Szolnok County (1280). | |

| 1282 | Roland of the Borsa clan | Ladislaus IV | First time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1282). | |

| 1283 | Apor of the Péc clan | Ladislaus IV | Also ispán of Szolnok County (1283). | |

| 1284–1294 | Roland of the Borsa clan | Ladislaus IV, Andrew III | Second time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1284–1294); fought against the invading Mongols in 1285; rebelled against both kings. | |

| 1287–c. 1288 (?) | Mojs of the Ákos clan | Ladislaus IV | Only one document mentions him as voivode; if so, he was also ispán of Szolnok County. | |

| 1295–1314 or 1315 | Ladislaus (III) of the Kán clan | Andrew III | Ruled almost independently; also ispán of Szolnok County (1295–1314). |

14th Century

| Term | Person in Office | King | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1315 | Ladislaus (IV) of the Kán clan | Declared himself voivode; son of Ladislaus (III) Kán (1295–1314). | ||

| 1315–1316 | Nicholas Meggyesi | Charles I | Could not take up his office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1315–1316). | |

| 1318–1321 | Dózsa Debreceni | Charles I | Also ispán of Szolnok County (1318–1321). | |

| 1321–1342 | Thomas Szécsényi | Charles I | Also ispán of Szolnok County (1321–1342), Arad County (1330–1342), and Csongrád County (1330). | |

| 1342–1344 | Nicholas Sirokai | Louis I | Also ispán of Arad and Szolnok Counties (1342–1344). | |

| 1344–1350 | Stephen Lackfi | Louis I | Also ispán of Arad and Szolnok Counties (1344–1350). | |

| 1350–1351 | Thomas Gönyűi or Csór | Louis I | Appointed by Stephen, the king's brother; also ispán of Arad and Szolnok Counties (1350–1351). | |

| 1351–1356 | Nicholas Kont of Orahovica | Louis I | Also ispán of Arad and Szolnok Counties (1351–1356). | |

| 1356–1359 | Andrew Lackfi | Louis I | Brother of Stephen Lackfi (1344–1350); also ispán of Arad and Szolnok Counties (1356–1359). | |

| 1359–1367 | Denis Lackfi | Louis I | Son of Stephen Lackfi (1344–1350); also ispán of Arad and Szolnok Counties (1359–1367). | |

| 1367–1368 | Nicholas Lackfi, Jr. | Louis I | Son of Stephen Lackfi (1344–1350); also ispán of Arad and Szolnok Counties (1367–1368). | |

| 1369–1372 | Emeric Lackfi | Louis I | Son of Stephen Lackfi (1344–1350); also ispán of Arad and Szolnok Counties (1369–1372). | |

| 1372–1376 | Stephen Lackfi of Csáktornya | Louis I | First time in office; son of Stephen Lackfi (1344–1350); also ispán of Szolnok County (1372–1376). | |

| 1376–1385 | Ladislaus Losonci, Sr. | Louis I, Mary | First time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1376–1385). | |

| 1385–1386 | Stephen Lackfi of Csáktornya | Charles II | Second time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1385–1386). | |

| 1386–1392 | Ladislaus Losonci, Sr. | Sigismund, Mary | Second time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1386–1392). | |

| 1392–1393 | Emeric Bebek | Sigismund, Mary | Also ispán of Szolnok County (1392–1393). | |

| 1393–1395 | Frank Szécsényi | Sigismund, Mary | Also ispán of Arad, Csongrád, and Szolnok Counties (1393–1395). | |

| 1395–1401 | Stibor of Stiboricz | Sigismund | First time in office; also ispán of Arad and Szolnok Counties (1395–1401). |

15th Century

| Term | Person in Office | King | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1401 | Simon Szécsényi | Sigismund | Also ispán of Szolnok County (1401). | |

| 1402–1403 | Nicholas Csáki | Sigismund | First time in office; also ispán of many counties including Szolnok (1402–1403); supported King Ladislaus of Naples's claim to the throne in 1403. | |

| Nicholas Marcali | Also ispán of many counties including Szolnok (1402–1403); joined the group supporting King Ladislaus of Naples's claim to the throne in 1403. | |||

| 1403–1409 | John Tamási | Sigismund | Also ispáns of Szolnok County (1403–1409). | |

| James Lack of Szántó | ||||

| 1409–1414 | Stibor of Stiboricz | Sigismund | Second time in office; also ispán of Szolnok County (1409–1414), and other areas. | |

| 1415–1426 | Nicholas Csáki | Sigismund | Second time in office; also ispán of Békés, Bihar, and Szolnok Counties (1415–1426). | |

| 1426–1437 | Ladislaus Csáki | Sigismund | Second time in office; served with Peter Cseh of Léva (1436–1437); also ispán of several counties; defeated by the rebellious peasants. | |

| 1436–1438 | Peter Cseh of Léva | Sigismund, Albert | Served with Ladislaus Csáki (1426–1437). | |

| 1438–1441 | Desiderius Losonci | Albert, Ladislaus V | Left Ladislaus V's side and joined Wladislas I in 1441. | |

| 1440–1441 | Ladislaus Jakcs | Wladislas I | ||

| Michael Jakcs | ||||

| 1441–1458 | Nicholas Újlaki | Wladislas I, Ladislaus V | First time in office; served with John Hunyadi (1441–1446), Emeric Bebek (1446–1448), and John Rozgonyi (1449–1458); also held many other important titles. | |

| 1441–1446 | John Hunyadi | Wladislas I | Served with Nicholas Újlaki (1441–1458); also held many other important titles, including regent-governor of Hungary (1446). | |

| 1446–1448 | Emeric Bebek | Elected by the Diet of Hungary | Served with Nicholas Újlaki (1441–1458); died fighting the Ottomans in the second Battle of Kosovo. | |

| 1449–1458 | John Rozgonyi | First time in office; served with Nicholas Újlaki (1441–1458); also ispán of Sopron and Vas Counties (1449–1454), and count of the Székelys (1457–1458). | ||

| 1459–1461 | Ladislaus Kanizsai | Matthias | Served with John and Sebastian Rozgonyi (1459–1460), and with his brother, Nicholas Kanizsai (1461). | |

| 1459–1460 | John Rozgonyi | Matthias | Served with Ladislaus Kanizsai (1459–1461), and with Sebastian Rozgonyi (1459–1460). | |

| 1459–1460 | Sebastian Rozgonyi | Matthias | Served with Ladislaus Kanizsai (1459–1461), and with John Rozgonyi (1459–1460). | |

| 1461 | Nicholas Kanizsai | Matthias | Served with his brother, Ladislaus Kanizsai (1459–1461). | |

| 1462–1465 | Nicholas Újlaki | Matthias | Second time in office. | |

| John Pongrác of Dengeleg | Matthias | First time in office. | ||

| 1465–1467 | Bertold Ellerbach of Monyorókerék | Matthias | Removed after rebellious Transylvanian nobles chose them as their leaders. | |

| Count Sigismund Szentgyörgyi | Brothers of Count Peter Szentgyörgyi (1498–1510); removed after rebellious Transylvanian nobles chose them as their leaders. | |||

| Count John Szentgyörgyi | ||||

| 1468–1474 | Nicholas Csupor of Monoszló | Matthias | Served with John Pongrác of Dengeleg (1468–1472). | |

| 1468–1472 | John Pongrác of Dengeleg | Matthias | Second time in office; served with Nicholas Csupor of Monoszló (1468–1474). | |

| 1472–1475 | Blaise Magyar | Matthias | Leader of Hungarian soldiers sent to help Stephen the Great, prince of Moldavia, in the Battle of Vaslui of 1475. | |

| 1475–1476 | John Pongrác of Dengeleg | Matthias | Third time in office. | |

| 1478–1479 | Peter Geréb of Vingárt | Matthias | ||

| 1479–1493 | Stephen (V) Báthory of Ecsed | Matthias, Wladislas II | ||

| 1493–1498 | Bartholomew Drágfi of Béltek | Wladislas II | Served with Ladislaus Losonci, Jr. (1493–1494); stopped a rebellion of the Székelys. | |

| 1493–1495 | Ladislaus Losonci, Jr. | Wladislas II | Served with Bartholomew Drágfi of Béltek (1493–1498). | |

| 1498–1510 | Count Peter Szentgyörgyi | Wladislas II | Brother of Counts Sigismund and John Szentgyörgyi (1465–1467). |

16th Century

| Term | Person in Office | King | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1510–1526 | John Zápolya (Szapolyai) | Wladislas II, Louis II | Later became king of Hungary. | |

| 1527–1529 | Péter Perényi | John Zápolya | Left John Zápolya's side and joined Ferdinand I. | |

| 1530–1534 | Stephen (VIII) Báthory of Somlyó | Ferdinand I | ||

| 1530 | Bálint Török | |||

| 1530–1534 | Jerome Laski | John Zápolya | Plotted against the king and was imprisoned. | |

| 1533–1534 | Emeric Czibak | |||

| 1534–1540 | Stephen Majláth of Szunyogszeg | John Zápolya | Served with Emeric Balassa of Gyarmat (1538–1540); planned to separate Transylvania from Hungary but was captured by the Ottomans. | |

| 1538–1540 | Emeric Balassa of Gyarmat | John Zápolya | Served with Stephen Majláth of Szunyogszeg (1534–1540); fled when the Ottomans invaded Transylvania. | |

| 1551 | George Martinuzzi | Ferdinand I | Also chosen as governor of Transylvania for the young King John Sigismund (1543–1551). | |

| 1552–1553 | Andrew Báthory of Ecsed | Ferdinand I | Resigned. | |

| 1553–1556 | Stephen Dobó | Ferdinand I | Last voivodes appointed by a king of Hungary. | |

| Francis Kendi | ||||

| 1571–1576 | Stephen Báthory | Chosen by the Three Nations and approved by the Ottoman Sultan Selim II; declared himself prince of Transylvania after becoming king of Poland in 1576. | ||

| 1576–1581 | Christopher Báthory | Stephen Báthory | ||

| 1581–1586 | Sigismund Báthory | Stephen Báthory | The last voivode; his title of prince of Transylvania was confirmed in 1595 by Emperor Rudolph. |

See also

- Vice-voivode of Transylvania

- Ban of Croatia

- Ban of Slavonia

- Governor of Transylvania

- Palatine (Kingdom of Hungary)

- Transylvania in the Middle Ages

- List of rulers of Transylvania

- List of chancellors of Transylvania