Arab–Byzantine wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Arab–Byzantine wars |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Muslim conquests | |||||

|

Greek fire, a special weapon used by the Byzantine Navy during these wars. |

|||||

|

|||||

| Belligerents | |||||

Ghassanids Mardaites Armenian principalities Bulgarian Empire Kingdom of Italy Italian city-states |

Medina Islamic Government Rashidun Caliphate Umayyad Caliphate Abbasid Caliphate Aghlabid Emirate of Abbasids Emirate of Sicily Emirate of Bari Emirate of Crete Hamdanids of Aleppo Fatimid Caliphate Mirdasids of Aleppo |

||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

| Heraclius Theodore Trithyrius † Gregory the Patrician † Vahan † Niketas the Persian † Constans II Constantine IV Justinian II Leontius Heraclius Constantine V Leo V the Armenian Michael Lachanodrakon Tatzates Irene of Athens Nikephoros I Theophilos Manuel the Armenian Niketas Ooryphas Himerios John Kourkouas Bardas Phokas the Elder Nikephoros II Phokas Leo Phokas the Younger John I Tzimiskes Michael Bourtzes Basil II Nikephoros Ouranos George Maniakes Tervel of Bulgaria |

Muhammad Al-Aziz Billah Manjutakin |

||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

| 8,000 in Bosra 50,000 at Yarmouk ~7,000 at Hazir 10,000+ at Iron Bridge |

300 at Dathin 130 in Bosra 3,000 at Yarmouk ~50,000 at Constantinople ~2,500 ships at Constantinople |

||||

| 4,000 civilian deaths at Dathin | |||||

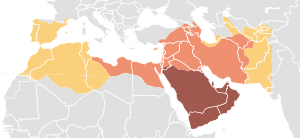

The Arab–Byzantine wars were a long series of conflicts between the Byzantine Empire (the eastern part of the old Roman Empire) and various Muslim-Arab empires. These wars lasted from the 7th to the 11th century. They began with the rapid expansion of the early Muslim states, like the Rashidun Caliphate and the Umayyad Caliphate.

In the 630s, Muslim Arabs from Arabia quickly took over the Byzantine Empire's southern lands, including Syria and Egypt. For the next 50 years, the Arabs launched many attacks into Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). They even tried to capture the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, twice. They also conquered the Byzantine lands in North Africa.

Things became more stable after the second major siege of Constantinople failed in 718. The Taurus Mountains then became a heavily guarded border between the two powers. Later, under the Abbasid Empire, relations improved, with periods of peace and diplomatic visits. However, battles and raids still happened almost every year until the 10th century.

For the first few centuries, the Byzantines mostly defended their lands. They tried to avoid big open battles, preferring to stay safe in their strong forts. After 740, they started launching their own attacks to try and win back lost lands. But the Abbasids often responded with huge invasions into Asia Minor. The Arabs also became strong at sea. From the 650s, the entire Mediterranean Sea became a battleground. Arab raids on islands and coastal towns became very common.

These Arab sea raids reached their peak in the 9th and early 10th centuries. This was after they conquered Crete, Malta, and Sicily. Their fleets even reached the coasts of France and Dalmatia.

The Abbasid Empire started to weaken and break apart after 861. At the same time, the Byzantine Empire grew stronger under the Macedonian dynasty. The tide of the wars slowly turned. From about 920 to 976, the Byzantines finally broke through Arab defenses. They took back control of northern Syria and Greater Armenia. The last century of these wars mostly involved border fights with the Fatimids in Syria. The border stayed mostly the same until the Seljuk Turks appeared after 1060.

Contents

How the Wars Started

Empires Before the Conflict

The long and difficult Byzantine–Sasanian wars in the 6th and 7th centuries weakened both the Byzantine and Persian empires. Many outbreaks of the Plague of Justinian also made them vulnerable. This left both empires exhausted when the Arabs suddenly emerged and expanded. The last war between the Roman (Byzantine) and Persian empires ended with a Byzantine victory. Emperor Heraclius got back all lost territories and returned the True Cross to Jerusalem in 629.

However, neither empire had time to recover. Within a few years, they faced conflict with the Arabs, who were newly united by Islam. This sudden rise of the Arabs was like a "human tsunami." Some historians believe the long Byzantine-Persian conflict opened the way for Islam's expansion.

In the late 620s, the Islamic Prophet Muhammad had already united much of Arabia under Muslim rule. He did this through conquests and alliances with tribes. The first Muslim-Byzantine clashes happened under his leadership. In 629, Arab and Byzantine troops met at the Battle of Mu'tah. This was after Muhammad's ambassador was killed by the Ghassanids, a kingdom allied with Byzantium. Muhammad died in 632. He was followed by Abu Bakr, the first Caliph. Abu Bakr gained full control of the Arabian Peninsula after the Ridda wars. This created a powerful Muslim state.

Muslim Conquests: 629–718

According to Muslim writings, Muhammad heard that Byzantine forces were gathering in northern Arabia to invade. He led a Muslim army north to Tabuk to attack them first. However, the Byzantine army had already left. This event was not a typical battle, but it was the first time Arabs met Byzantines in a military way. It did not lead to immediate fighting.

There are no Byzantine records from that time about the Tabuk expedition. Many details come from later Muslim sources. Some believe one Byzantine source might refer to the Battle of Mu'tah from 629, but it's not certain. The first fights might have started as conflicts with Arab states allied to the Byzantine and Sassanid empires. These were the Ghassanids and the Lakhmids. After 634, Muslim Arabs definitely began a full attack on both empires. This led to the conquest of the Levant, Egypt, and Persia for Islam. The most successful Arab generals were Khalid ibn al-Walid and 'Amr ibn al-'As.

Arab Conquest of Roman Syria: 634–638

In the Levant, the invading Rashidun army fought a Byzantine army. This army included imperial troops and local fighters. Some historians say that local Christians and Jews in Syria welcomed the Arabs. They were unhappy with Byzantine rule.

The Roman Emperor Heraclius was sick and could not lead his armies. He could not stop the Arab conquests of Syria and Roman Paelestina in 634. In a battle near Ajnadayn in the summer of 634, the Rashidun Caliphate army won a major victory. After winning at Fahl, Muslim forces conquered Damascus in 634. This was under the command of Khalid ibn al-Walid. The Byzantines gathered all available troops. Major commanders like Theodore Trithyrius and the Armenian general Vahan tried to push the Muslims out.

However, at the Battle of Yarmouk in 636, the Muslims used the land to their advantage. They tricked the Byzantines into a big battle, which the Byzantines usually avoided. The Byzantines suffered huge losses in the deep valleys and cliffs. Emperor Heraclius was very disappointed when he left Antioch for Constantinople. He reportedly said, "Peace unto thee, O Syria, and what an excellent country this is for the enemy!" The loss of Syria greatly affected the Byzantines.

In April 637, the Arabs captured Jerusalem after a long siege. Patriarch Sophronius surrendered the city. In the summer of 637, the Muslims conquered Gaza. Around the same time, Byzantine leaders in Egypt and Mesopotamia bought expensive truces. These truces lasted three years for Egypt and one year for Mesopotamia. Antioch fell to the Muslim armies in late 637. By then, the Muslims controlled all of northern Syria, except for upper Mesopotamia. They had a one-year truce there.

When this truce ended in 638–639, the Arabs took over Byzantine Mesopotamia and Byzantine Armenia. They finished conquering Palestine by attacking Caesarea Maritima and finally capturing Ascalon. In December 639, the Muslims left Palestine to invade Egypt in early 640.

Arab Conquests of North Africa: 639–698

Conquest of Egypt and Cyrenaica

By the time Heraclius died, much of Egypt was lost. By 637–638, all of Syria was under Muslim control. With 3,500–4,000 troops, 'Amr ibn al-A'as entered Egypt from Palestine in late 639 or early 640. He received more soldiers, including 12,000 from Zubayr ibn al-Awwam. 'Amr first besieged and conquered Babylon Fortress. Then he attacked Alexandria. The Byzantines were divided and shocked by losing so much land. They agreed to give up Alexandria by September 642. The fall of Alexandria ended Byzantine rule in Egypt. This allowed the Muslims to continue their expansion into North Africa. Between 643 and 644, 'Amr finished conquering Cyrenaica. Uthman became Caliph after Umar died.

Arab historians say that local Christian Copts welcomed the Arabs. This was similar to how the Monophysites welcomed them in Jerusalem. Losing this rich province meant the Byzantines lost their valuable wheat supply. This caused food shortages across the Byzantine Empire and weakened its armies.

The Byzantine navy briefly took back Alexandria in 645. But they lost it again in 646 after the Battle of Nikiou. Islamic forces raided Sicily in 652. Cyprus and Crete were captured in 653.

Conquest of the Exarchate of Africa

In 647, a Rashidun-Arab army led by Abdallah ibn al-Sa’ad invaded the Byzantine Exarchate of Africa. They conquered Tripolitania, then Sufetula, about 150 miles (240 km) south of Carthage. The governor of Africa, Gregory, was killed. Abdallah's army returned to Egypt in 648 with much treasure. Gregory's successor, Gennadius, promised them an annual payment of about 300,000 nomismata (gold coins).

After a civil war in the Arab Empire, the Umayyads came to power under Muawiyah I. Under the Umayyads, they finished conquering the remaining Byzantine and Berber lands in North Africa. The Arabs then moved into Visigothic Spain through the Strait of Gibraltar. This was led by the general Tariq ibn-Ziyad. But this happened only after they built their own navy. They conquered and destroyed the Byzantine stronghold of Carthage between 695 and 698. Losing Africa meant that a new, growing Arab fleet from Tunisia soon challenged Byzantine control of the Western Mediterranean.

Muawiyah began to unite Arab lands from the Aral Sea to Egypt's western border. He placed a governor in Egypt at al-Fustat. He also launched raids into Anatolia in 663. Then, from 665 to 689, a new North African campaign started. This was to protect Egypt from attacks by Byzantine Cyrene. An Arab army of 40,000 took Barca, defeating 30,000 Byzantines.

A group of 10,000 Arabs under Uqba ibn Nafi followed from Damascus. In 670, Kairouan (modern Tunisia) was set up as a base for more invasions. Kairouan became the capital of the Islamic province of Ifriqiya. It also became a major Arab-Islamic religious center in the Middle Ages. Then ibn Nafi "went deep into the country, crossed the wilderness, and reached the edge of the Atlantic and the great desert".

In his conquest of the Maghreb, Uqba Ibn Nafi took the coastal cities of Bejaia and Tangier. He overcame what was once the Roman province of Mauretania. There, he was finally stopped by Count Julian.

Arab Attacks on Anatolia and Sieges of Constantinople

As the first wave of Muslim conquests ended, a border formed between the two powers. A wide, empty zone appeared in Cilicia. This was along the southern parts of the Taurus and Anti-Taurus ranges. Syria was in Muslim hands, and the Anatolian plateau was Byzantine. Both Emperor Heraclius and Caliph 'Umar (ruled 634–644) tried to destroy this zone. They wanted it to be a strong barrier between their lands.

However, the Umayyads still wanted to fully conquer Byzantium. Their beliefs taught them that the Byzantines were in the Dār al-Ḥarb, the "House of War." This meant Muslims should attack whenever possible. Peace was seen as temporary, and true peace would only come if the enemy accepted Islam or paid tribute.

Muawiyah I (ruled 661–680) was the main leader of the Muslim effort against Byzantium. He created a fleet that challenged the Byzantine navy. This fleet raided Byzantine islands and coasts. To stop Byzantine attacks from the sea, Muawiyah built a navy in 649. It was manned by Christian and Muslim sailors. This led to the defeat of the Byzantine navy at the Battle of the Masts in 655. This opened up the Mediterranean Sea to Arab expansion. 500 Byzantine ships were destroyed, and Emperor Constans II almost died. Under Caliph Uthman ibn Affan's orders, Muawiyah then prepared for the siege of Constantinople.

Trade between the Muslim and Christian shores almost stopped during this time. This isolated Western Europe from the Muslim world. Muawiyah also started the first large raids into Anatolia from 641. These attacks aimed to get treasure, weaken the Byzantines, and keep them busy. The Byzantines responded with their own raids. These raids became a regular part of Byzantine–Arab warfare for three centuries.

A Muslim Civil War in 656 gave Byzantium a chance to breathe. Emperor Constans II (ruled 641–668) used this time to strengthen his defenses. He also started a major army reform: the creation of the themata. These were large military districts in Anatolia, the main land remaining to the Empire. Soldiers were given land in these districts for their service. The themata became the backbone of the Byzantine defense for centuries.

Attacks on Byzantine Lands

After winning the civil war, Muawiyah launched attacks on Byzantine lands in Africa, Sicily, and the East. By 670, the Muslim fleet reached the Sea of Marmara and stayed at Cyzicus for the winter. Four years later, a huge Muslim fleet returned to the Marmara. They used Cyzicus as a base to raid Byzantine coasts. Finally, in 676, Muawiyah sent an army to attack Constantinople by land. This began the First Arab Siege of the city. However, Constantine IV (ruled 661–685) used a powerful new weapon called "Greek fire." This weapon was invented by Kallinikos, a Christian refugee from Syria. It helped the Byzantines defeat the Umayyad navy in the Sea of Marmara. The siege was lifted in 678. The returning Muslim fleet suffered more losses from storms. The army lost many men to Byzantine armies attacking them on their way back.

Among those killed in the siege was Eyup, a close companion of Muhammad. His tomb is now a holy site in Istanbul. The Byzantine victory stopped Islamic expansion into Europe for almost 30 years.

The defeat at Constantinople was followed by more problems across the Muslim empire. As historian Gibbon wrote, "this Mahometan Alexander... was unable to preserve his recent conquests." His forces had to deal with rebellions. He was killed in one such battle. Then, the third governor of Africa, Zuheir, was defeated by a strong army sent from Constantinople. Meanwhile, a second Arab civil war raged in Arabia and Syria. This led to four different caliphs between Muawiyah's death in 680 and Abd al-Malik becoming caliph in 685. The civil war continued until 692.

The wars of Justinian II (ruled 685–695 and 705–711) showed the general disorder of the time. After a successful campaign, he made a truce with the Arabs. They agreed to share control of Armenia, Iberia, and Cyprus. However, by moving 12,000 Christian Mardaites from Lebanon, he removed a major obstacle for the Arabs in Syria. In 692, after the terrible Battle of Sebastopolis, the Muslims invaded and conquered all of Armenia. Justinian was removed from power in 695. Carthage was lost in 698. Justinian returned to power from 705 to 711. His second reign was marked by Arab victories in Asia Minor and civil unrest.

Justinian's removal from power twice led to internal disorder. There were many revolts and emperors who lacked support. In this situation, the Umayyads strengthened their control of Armenia and Cilicia. They began preparing a new attack on Constantinople. In Byzantium, the general Leo the Isaurian (ruled 717–741) had just become emperor in March 717. At that time, a huge Muslim army under the famous Umayyad prince Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik began moving towards the capital. The Caliphate's army and navy, led by Maslama, had about 120,000 men and 1,800 ships, according to sources. Whatever the real number, it was a massive force, much larger than the Byzantine army. Luckily for Leo and the Empire, the city's sea walls had recently been repaired and strengthened. Also, the emperor made an alliance with the Bulgar khan Tervel. Tervel agreed to attack the invaders from behind.

From July 717 to August 718, the city was besieged by land and sea by the Muslims. They built a long double line of walls on the land side, cutting off the capital. However, their attempt to block the city by sea failed. The Byzantine navy used Greek fire against them. The Arab fleet stayed far from the city walls, leaving Constantinople's supply routes open. The besieging army had to stay through winter. They suffered terrible losses from the cold and lack of food.

In spring, new reinforcements were sent by the new caliph, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz (ruled 717–720). These came by sea from Africa and Egypt, and by land through Asia Minor. The crews of the new fleets were mostly Christians, and many of them deserted. The land forces were ambushed and defeated in Bithynia. As hunger and disease continued in the Arab camp, the siege was given up on August 15, 718. On its way back, the Arab fleet suffered more losses from storms and a volcano eruption.

Stabilizing the Border: 718–863

The first wave of Muslim conquests ended with the siege of Constantinople in 718. The border between the two empires became stable along the mountains of eastern Anatolia. Raids and counter-raids continued, almost like a ritual. But the idea of the Caliphate completely conquering Byzantium faded. This led to more regular, and often friendly, diplomatic contacts. Both empires began to recognize each other.

To deal with the Muslim threat, which was strongest in the early 8th century, the Isaurian emperors adopted Iconoclasm. This policy involved banning religious images (icons). It was stopped in 786, brought back in the 820s, and finally ended in 843. Under the Macedonian dynasty, the Byzantines slowly went on the attack. This was because the Abbasid Caliphate was weakening and breaking apart. The Byzantines took back much territory in the 10th century. However, these lands were lost again after 1071 to the Seljuk Turks.

Raids and the Rise of Iconoclasm

After failing to capture Constantinople in 717–718, the Umayyads focused elsewhere for a time. This allowed the Byzantines to attack and gain some land in Armenia. However, from 720/721, Arab armies restarted their expeditions against Byzantine Anatolia. These were no longer aimed at full conquest. Instead, they were large raids, meant to plunder and destroy the countryside. They only sometimes attacked forts or major towns.

Under the later Umayyad and early Abbasid caliphs, the border between Byzantium and the Caliphate became stable. It ran along the Taurus-Antitaurus mountain ranges. On the Arab side, Cilicia was permanently taken. Its empty cities, like Adana and Tarsus, were rebuilt and resettled by the early Abbasids. In Upper Mesopotamia, places like Germanikeia and Melitene became important military centers. These two regions formed a new fortified border zone, called the thughur.

Both the Umayyads and later the Abbasids saw annual expeditions against Byzantium as part of their jihad (holy struggle). These expeditions became very organized. There were usually one or two summer attacks, sometimes with a naval attack. Winter expeditions also happened. The summer attacks were often two separate forces. One came from the Cilician thughur (mostly Syrian troops). The other, usually larger, came from Malatya (Mesopotamian troops). The raids mostly stayed in the borderlands and central Anatolian plateau. They rarely reached the coast, which the Byzantines heavily fortified.

Under the more aggressive Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (ruled 723–743), Arab expeditions became more intense. They were led by some of the Caliphate's best generals. This was a time when Byzantium was fighting for survival. The border areas were ruined by war, with destroyed cities and empty villages. People relied on rocky castles or mountains for safety, not the empire's armies.

In response to new Arab invasions and natural disasters, Emperor Leo III the Isaurian believed the Empire had lost God's favor. In 722, he tried to force Jews to convert. Soon, he focused on the worship of icons (religious images). Some bishops thought this was idol worship. In 726, Leo issued an order against using icons. He formally banned religious images in a council in 730.

This decision caused major opposition from both the people and the church, especially the Bishop of Rome. Leo did not consider their views. This controversy weakened the Byzantine Empire. It was a key reason for the split between the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Bishop of Rome.

The Umayyad Caliphate was busy with other conflicts, especially with the Khazars. Leo III made an alliance with the Khazars. His son and heir, Constantine V (ruled 741–775), married a Khazar princess. Only in the late 730s did Muslim raids become a threat again. But a big Byzantine victory at Akroinon and the chaos of the Abbasid Revolution paused Arab attacks. This also allowed Constantine V to take a more aggressive stance. In 741, he attacked the major Arab base of Melitene and won more victories. Leo III and Constantine saw these successes as a sign of God's favor. This strengthened the position of Iconoclasm in the Empire.

Early Abbasids

Unlike the Umayyads, the Abbasid caliphs did not actively try to expand their empire. They were generally happy with their existing borders. Any wars they fought were usually in response to attacks or to show their power. However, campaigns against Byzantium were still important for their own people. The yearly raids, which had almost stopped after the Abbasid Revolution, started again strongly around 780. These were the only expeditions where the Caliph or his sons personally took part.

Caliph Harun al-Rashid (ruled 786–809) was the most energetic Abbasid ruler in fighting Byzantium. He wanted to show his devotion and leadership. He moved his capital to Raqqa, near the border. In 786, he added a second line of defense in northern Syria, called the al-'Awasim. He was known for spending alternating years leading the Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) and leading a campaign into Anatolia. In 806, he led the largest expedition ever assembled by the Abbasids.

His reign also saw more regular contact between the Abbasid court and Byzantium. They exchanged ambassadors and letters much more often than under the Umayyad rulers. Despite Harun's hostility, these exchanges showed that the Abbasids accepted Byzantium as an equal power.

Civil war happened in the Byzantine Empire, often with Arab support. With the help of Caliph Al-Ma'mun, Arabs led by Thomas the Slav invaded. Within months, only two themata (military districts) in Asia Minor remained loyal to Emperor Michael II. When the Arabs captured Thessalonica, the Empire's second-largest city, the Byzantines quickly took it back. Thomas's siege of Constantinople in 821 failed to get past the city walls, and he had to retreat.

The Arabs did not give up their plans for Asia Minor. In 838, they began another invasion, sacking the city of Amorion.

Sicily, Italy, and Crete

While the East had a somewhat stable situation, the western Mediterranean changed greatly. The Aghlabids began their slow conquest of Sicily in the 820s. Using Tunisia as their starting point, the Arabs conquered Palermo in 831, Messina in 842, and Enna in 859. This ended with the capture of Syracuse in 878.

This opened up southern Italy and the Adriatic Sea to raids and settlement. Byzantium suffered another major loss when Crete was taken by a group of exiles from al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). They set up a pirate state on the island. For over a century, they attacked the coasts of the previously safe Aegean Sea.

Byzantine Comeback: 863–11th Century

In 863, during the rule of Michael III, the Byzantine general Petronas defeated an Arab invasion force. This force was led by Umar al-Aqta at the Battle of Lalakaon. The Byzantines caused heavy losses and removed the Emirate of Melitene as a serious military threat. Umar died in battle, and the rest of his army was destroyed in later fights. The Byzantines celebrated this victory as revenge for the earlier Arab sacking of Amorion. News of the defeats caused riots in Baghdad and Samarra. In the following months, the Byzantines successfully invaded Armenia. They killed the Muslim governor in Armenia, Emir Ali ibn Yahya, and the Paulician leader Karbeas. These Byzantine victories marked a turning point. They began a century-long Byzantine offensive eastward into Muslim territory.

Religious peace came with the rise of the Macedonian dynasty in 867. This brought strong and unified Byzantine leadership. Meanwhile, the Abbasid empire had split into many groups after 861. Basil I brought the Byzantine Empire back as a regional power. During this time, the empire expanded its territory. It became the strongest power in Europe. Basil also had good relations with Rome in church matters. He allied with the Holy Roman Emperor Louis II against the Arabs. His fleet cleared the Adriatic Sea of Arab raids.

With Byzantine help, Louis II captured Bari from the Arabs in 871. The city became Byzantine territory in 876. The Byzantine position on Sicily worsened. Syracuse fell to the Emirate of Sicily in 878. Catania was lost in 900, and finally the fortress of Taormina in 902. Michael of Zahumlje reportedly sacked Siponto, a Byzantine town in Apulia, on July 10, 926. Sicily remained under Arab control until the Norman invasion in 1071.

Even though Sicily was lost, the general Nikephoros Phokas the Elder managed to take Taranto and much of Calabria in 880. This formed the base for the later Catepanate of Italy. The successes in the Italian Peninsula began a new period of Byzantine control there. Most importantly, the Byzantines started to have a strong presence in the Mediterranean Sea, especially the Adriatic.

Under John Kourkouas, the Byzantines conquered the emirate of Melitene. This was one of the strongest Muslim border states. They also took Theodosiopolis and advanced into Armenia in the 930s. The next three decades were dominated by the struggle of the Phokas family against the Hamdanid emir of Aleppo, Sayf al-Dawla. Al-Dawla was finally defeated by Nikephoros II Phokas. Nikephoros conquered Cilicia and northern Syria, including the sacking of Aleppo, and took back Crete. His nephew and successor, John I Tzimiskes, pushed even further south, almost reaching Jerusalem. But his death in 976 ended Byzantine expansion towards Palestine.

After ending internal conflicts, Basil II launched a counter-campaign against the Arabs in 995. The Byzantine civil wars had weakened the Empire's position in the east. The gains of Nikephoros II Phokas and John I Tzimiskes were almost lost. Aleppo was under siege, and Antioch was threatened. Basil won several battles in Syria. He relieved Aleppo, took over the Orontes valley, and raided further south. He did not have enough force to go into Palestine and reclaim Jerusalem. However, his victories did restore much of Syria to the empire. This included the large city of Antioch, which was the seat of its Patriarch.

No Byzantine emperor since Heraclius had been able to hold these lands for long. The Empire would keep them for the next 110 years until 1078. By 1025, Byzantine land stretched from the Straits of Messina in the west to the River Danube and Crimea in the north. In the east, it reached the cities of Melitene and Edessa beyond the Euphrates.

Under Basil II, the Byzantines created many new themata. These stretched northeast from Aleppo (a Byzantine protectorate) to Manzikert. With the Theme system of military and administrative government, the Byzantines could raise an army of at least 200,000 soldiers. These were placed strategically throughout the Empire. With Basil's rule, the Byzantine Empire reached its greatest size in nearly five centuries.

Conclusion of the Wars

The wars came to an end as new threats emerged. Turks and various Mongol invaders replaced the earlier conflicts. From the 11th and 12th centuries, Byzantine conflicts shifted to the Byzantine-Seljuk wars. The Seljuk Turks took over the Islamic invasion of Anatolia.

After the defeat at the Battle of Manzikert by the Turks in 1071, the Byzantine Empire sought help from Western Crusaders. It re-established its position as a major power in the Middle East. Meanwhile, the major Arab conflicts were the Crusades and later against Mongolian invasions.

Effects of the Wars

These long Byzantine–Arab Wars had lasting effects on both the Byzantine Empire and the Arab world. The Byzantines lost a lot of land. However, while the Arabs gained strong control in the Middle East and Africa, their further conquests in Western Asia were stopped. The Byzantine Empire's main focus changed. Instead of trying to reconquer western lands, it focused on defending its eastern borders against Islamic armies. Without Byzantine interference in the new Christian states of western Europe, feudalism and economic self-sufficiency grew greatly.

Historians believe one of the most important effects was the strain on the relationship between Rome and Byzantium. While fighting for survival against the Islamic armies, the Empire could no longer protect the Papacy as it once had. Worse, emperors often interfered in church matters beyond their role. The Iconoclast controversy in the 8th and 9th centuries was a key factor. It pushed the Latin Church closer to the Franks. Some argue that Charlemagne was indirectly a product of Muhammad. The Frankish Empire might not have existed without Islam.

The Holy Roman Empire of Charlemagne's successors later helped the Byzantines during the Crusades. But relations between the two empires remained difficult. Emperor Basil sent an angry letter to his western counterpart, Louis II. He scolded Louis for using the title of emperor. Basil argued that Frankish rulers were simply reges (kings). He said each nation has its own ruler title, but the imperial title only suited the ruler of the Eastern Romans, Basil himself.

Historical Sources

Historian Walter Emil Kaegi notes that Arabic sources have been studied a lot for their unclear parts and contradictions. However, Byzantine sources are also problematic. Chronicles by Theophanes and Nicephorus, and those in Syriac, are short and brief. The question of their sources and how they used them remains unsolved. Kaegi concludes that Byzantine writings also need careful review. They "contain bias and cannot serve as an objective standard" to check Muslim sources.

Among the few Latin sources are the 7th-century history by Fredegarius. There are also two 8th-century Spanish chronicles. All these use some Byzantine and Eastern historical traditions. Regarding Byzantine military actions against the early Muslim invasions, Kaegi states that "Byzantine traditions... try to shift blame for the Byzantine disaster from Heraclius to other people, groups, and things."

Many other Byzantine sources exist. These include papyri, sermons (like those by Sophronius and Anastasius Sinaita), poetry, letters, religious writings, prophecies, saints' lives, and military manuals. Other non-written sources include inscriptions, archaeology, and coins. None of these sources give a full story of the Muslim army campaigns and conquests. But some do contain very important details found nowhere else.

See also

In Spanish: Guerras árabo-bizantinas para niños

In Spanish: Guerras árabo-bizantinas para niños

- Aegyptus (Roman province)

- Battle of Tours

- Byzantine–Ottoman Wars

- Byzantine–Seljuk wars

- Early Muslim conquests

- Spread of Islam

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |