- This page was last modified on 1 January 2026, at 00:05. Suggest an edit.

al-Mu'tasim facts for kids

| al-Mu'tasim المعتصم |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caliph Commander of the Faithful |

|||||

Gold dinar of al-Mu'tasim, minted in Baghdad in 839

|

|||||

| 8th Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 9 August 833 – 5 January 842 | ||||

| Predecessor | al-Ma'mun | ||||

| Successor | al-Wathiq | ||||

| Born | October 796 Khuld Palace, Baghdad |

||||

| Died | 5 January 842 (aged 45) Jawsaq Palace, Samarra |

||||

| Burial | Jawsaq Palace, Samarra | ||||

| Consorts | Badhal Qaratis Shuja Qurut al-Ayn |

||||

| Issue |

|

||||

|

|||||

| Dynasty | Abbasid | ||||

| Father | Harun al-Rashid | ||||

| Mother | Marida bint Shabib | ||||

| Religion | Mu'tazili Islam | ||||

Al-Mu'tasim (born October 796, died January 5, 842) was the eighth Abbasid caliph. He ruled from 833 until his death in 842. His full name was Abū Isḥāq Muḥammad ibn Hārūn al-Muʿtaṣim biʾllāh. This means "He who seeks refuge in God."

Al-Mu'tasim was a younger son of Caliph Harun al-Rashid. He became important by creating his own army. This army was mostly made up of Turkic slave-soldiers called ghilmān. His half-brother, Caliph al-Ma'mun, used this army. It helped balance other powerful groups in the government. They also fought in battles against rebels and the Byzantine Empire.

When al-Ma'mun died suddenly in 833, al-Mu'tasim was in a good position to become the next caliph. He took over, even though al-Ma'mun's son al-Abbas also had a claim.

Al-Mu'tasim continued some of his brother's policies. He worked with the Tahirids, who governed Khurasan and Baghdad. He also continued to support the Mu'tazili Islamic idea. This led to the persecution of those who disagreed, through an inquisition called the miḥna.

His rule also brought big changes. He created a new government focused on the military, especially his Turkish guard. In 836, he built a new capital city called Samarra. This showed the new power of the military. It also moved the government away from the people of Baghdad, who sometimes caused trouble.

The power of the caliph's government grew. It became more centralized. This meant less power for local governors. Instead, a small group of military and government leaders in Samarra gained more control. The state's money was increasingly used to pay for the professional army, which was mostly Turkish.

The old Arab and Iranian leaders lost their influence. A plot against al-Mu'tasim in 838, in favor of al-Abbas, led to many of them being removed. This made the Turkish leaders, like Ashinas, Wasif, Itakh, and Bugha, even stronger. Another important person, al-Afshin, was later overthrown and killed in 840/1. The rise of the Turks eventually caused problems later on, but al-Mu'tasim's system of using ghulām soldiers was copied by many Muslim rulers.

Al-Mu'tasim's rule was full of wars. He fought against the Khurramite uprising led by Babak Khorramdin in Adharbayjan. This rebellion was put down by al-Afshin between 835 and 837. He also fought against Mazyar, the ruler of Tabaristan, who rebelled against the Tahirids.

Al-Mu'tasim himself led a major war against the Byzantine Empire in 838. His armies defeated Emperor Theophilos. They then sacked the city of Amorium. This victory was greatly celebrated. It helped al-Mu'tasim become known as a strong warrior-caliph.

Contents

Early Life of Al-Mu'tasim

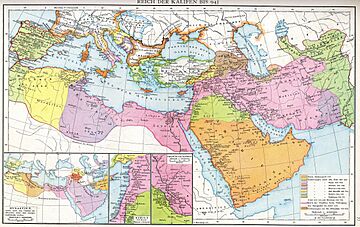

Map of the Muslim expansion during the 7th and 8th centuries and of the Muslim world under the Umayyad and early Abbasid caliphates, from the Allgemeiner historischer Handatlas of Gustav Droysen (1886)

Muhammad, who would become al-Mu'tasim, was born in the Khuld Palace in Baghdad. The exact date is not fully clear. Historians say he was born in October 796 CE. His parents were the fifth Abbasid caliph, Harun al-Rashid, and Marida bint Shabib. Marida was a slave concubine. She was born in Kufa, but her family came from Soghdia. She is thought to have been of Turkic origin.

Al-Mu'tasim's early life was during a "golden age" for the Abbasid Caliphate. The empire was very rich and powerful. Trade routes linked Tang China and the Indian Ocean with Europe and Africa. Baghdad was at the center of these routes. This brought great wealth. Harun al-Rashid could send large armies against the Byzantine Empire. He also had strong diplomatic ties, even with Charlemagne. This wealth also supported religious scholars and poets. The caliph's court was very grand.

Al-Mu'tasim's Time with Al-Ma'mun

As an adult, Muhammad was known as Abu Ishaq. He was described as strong and active. He loved physical activities. This was different from earlier caliphs who preferred to stay in one place. Some later writers said he could barely read. But historians believe this just meant he wasn't very interested in books or learning.

Civil War and Abu Ishaq's Role

Abu Ishaq was one of Harun's younger sons. He was not expected to become caliph. After Harun died in 809, a civil war started. His older half-brothers, al-Amin and al-Ma'mun, fought for power. Al-Amin had support from the old Abbasid leaders in Baghdad. Al-Ma'mun was supported by other groups.

Al-Ma'mun won in 813. He stayed in Khurasan and let his helpers rule in Iraq. This made many people in Baghdad angry. They did not like al-Ma'mun's "Persian" helpers. In 817, they even chose another caliph, Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi. This made al-Ma'mun realize he needed to return. He came back to Baghdad in 819 to rebuild the government.

During this time, Abu Ishaq stayed in Baghdad. He led the Hajj pilgrimage in 816 and 817. He was loyal to al-Ma'mun at first. But like many others, he supported Ibrahim against al-Ma'mun for a while.

Building the Turkish Guard

Around 814 or 815, Abu Ishaq started his own army of Turkish soldiers. At first, he bought slaves in Baghdad and trained them. Later, Turkish slaves were sent from Central Asia. This was part of an agreement with the local Samanid rulers. This private army was small, maybe three to four thousand men. But they were highly trained and disciplined. This made Abu Ishaq a powerful figure.

Special military uniforms were created for this Turkish guard. The civil war had weakened the old Abbasid army. Al-Ma'mun needed a strong and loyal army. He turned to "new men" who had their own soldiers. These included the Tahirids and his brother Abu Ishaq. Abu Ishaq's Turkish army helped al-Ma'mun. It balanced the power of other leaders, especially those from eastern Iran.

The "Turkish slave soldiers" are a debated topic. Many were slaves, but they were paid salaries. They were called mawālī (clients) or ghilmān (pages). This suggests they were freed. Some early members were not Turks or slaves. They were Iranian princes from Central Asia, like al-Afshin. They brought their own soldiers. It's thought that al-Ma'mun might have encouraged the creation of this guard. It became a private army for Abu Ishaq, but it also served the caliph.

Abu Ishaq's Service to Al-Ma'mun

In 819, Abu Ishaq and his Turkish guard helped put down a rebellion. This was a Kharijite uprising north of Baghdad. In 828, al-Ma'mun made Abu Ishaq governor of Egypt and Syria. The situation in Egypt was still difficult. When Abu Ishaq's deputy tried to raise taxes, people revolted. In 830, Abu Ishaq went to Egypt himself with his 4,000 Turks. They defeated the rebels.

In 831, Abu Ishaq joined al-Ma'mun in a war against the Byzantines. They captured and destroyed several forts. They also took the town of Tyana. Later, the revolt in Egypt started again. This time, both Arab settlers and Christian Copts rebelled. Al-Afshin led the Turkish troops against them. He won many battles. Many Copts were executed, and their families were sold into slavery. The old Arab leaders in Egypt were almost wiped out.

In 832, al-Ma'mun invaded Byzantine lands again. He captured the fortress of Loulon. Al-Ma'mun was so confident that he planned to capture Constantinople. Al-Abbas was sent to prepare Tyana as a military base. Al-Ma'mun followed in July, but he suddenly became ill and died on August 7, 833.

Becoming Caliph

Al-Ma'mun had not officially named his successor. His son, al-Abbas, was old enough and had military experience. But he was not named heir. Some say al-Ma'mun named his brother, Abu Ishaq, as his successor just before he died. Abu Ishaq became caliph on August 9, 833. He took the name al-Mu'tasim.

It is not clear if this was exactly how it happened. Abu Ishaq was close to his dying brother. Al-Abbas was not there. Many soldiers preferred al-Abbas. They even tried to make him caliph. But al-Abbas refused, perhaps to avoid another civil war. He swore loyalty to his uncle. Only then did the soldiers accept al-Mu'tasim. Because his position was not fully secure, al-Mu'tasim stopped the military expedition and returned to Baghdad.

New Leaders and Government

Al-Mu'tasim became caliph because he had his own strong army, the Turkish corps. He relied almost entirely on his Turks. His rule brought a big change to the Abbasid government. It became very military-focused. This was a major shift in Islamic history.

The old Arab and Iranian leaders lost their power. The Turkish military gained more influence. The government became more centralized. This meant more control from the caliph's court. For example, in Egypt, Arab families used to get salaries from local taxes. Al-Mu'tasim stopped this. He ordered that all Egyptian taxes be sent to the central government. Only the Turkish soldiers in Egypt would get cash salaries from Samarra.

Al-Mu'tasim also appointed his top Turkish leaders, like Ashinas and Itakh, as governors over several provinces. They did not rule directly. Instead, they appointed deputies. This gave them direct access to money for their troops. It also centralized power even more. The caliph's government now had strong authority to collect taxes from all provinces.

The Tahirids were an exception. They remained powerful governors in the eastern Caliphate. They also provided the governor of Baghdad. This helped keep Baghdad peaceful. Al-Mu'tasim's government also relied on financial experts. These officials were often Persian or Aramaic. Many were new converts to Islam, and some were even Christians.

Al-Mu'tasim's chief minister was al-Fadl ibn Marwan. He was careful with money. But he was dismissed in 836 because he refused to let the caliph give expensive gifts. He said the treasury could not afford it. His replacement, Muhammad ibn al-Zayyat, was a rich merchant. He was good with money but also harsh. He stayed in his job until after al-Mu'tasim's death.

The Growing Power of the Turks

Al-Mu'tasim relied more and more on his Turkish ghilmān. This was especially true after a plot against him was discovered in 838. This plot happened during the Amorium campaign. Some old Abbasid leaders were unhappy with al-Mu'tasim's policies. They did not like his favoritism towards the Turks. They planned to kill the caliph and replace him with al-Ma'mun's son, al-Abbas.

The plot was discovered. Al-Abbas was imprisoned. The Turkish leaders Ashinas, Itakh, and Bugha the Elder arrested the other plotters. This led to a big removal of people from the army. Al-Abbas was forced to die of thirst. Many other leaders of the plot were executed. This strengthened the position of the Turks and their commanders.

Ashinas became very powerful. In 839, his daughter married al-Afshin's son. In 840, al-Mu'tasim made Ashinas his deputy when he was away from Samarra. Ashinas was also made super-governor over Egypt, Syria, and the Jazira. He did not rule these areas directly but appointed others.

In 840, al-Afshin himself fell out of favor. Despite being a great general, he was disliked by the other Turkish generals. He was also accused of encouraging Mazyar to rebel against the Tahirids. Al-Afshin was accused of plotting against al-Mu'tasim and being a false Muslim. He was put on trial and found guilty. He died in prison, perhaps from starvation or poison. His body was displayed and then burned. This event further increased the power of the Turkish leaders, especially Wasif.

However, al-Mu'tasim was not always happy with the men he had promoted. He once said that his brother al-Ma'mun had chosen good servants. But he felt he had chosen poorly with al-Afshin, Ashinas, Itakh, and Wasif. He realized that he had chosen men who had no strong ties to the Muslim community.

Building Samarra, the New Capital

At first, the Turkish army lived in Baghdad. But they often clashed with the local people. The people of Baghdad were angry because they lost influence to the foreign troops. The Turkish soldiers were sometimes undisciplined and violent. They often did not speak Arabic. Many were new converts to Islam or not Muslim at all.

This conflict was a main reason why al-Mu'tasim decided to build a new capital. In 836, he founded Samarra, about 80 miles north of Baghdad. Building a new capital showed that a new government was in charge. It allowed the court to be far from the people of Baghdad. It was protected by the new foreign guard.

In Samarra, areas were carefully planned. Residential areas were separate from markets. The military had its own areas. Each area was for a specific group of soldiers, like the Turks. The city was filled with grand mosques and palaces. These were built by the caliphs and their commanders. Unlike Baghdad, Samarra was a completely new city. It was built just for the caliph's court. When the capital moved back to Baghdad 60 years later, Samarra was quickly abandoned. This is why its ruins are still well-preserved today.

Science and Learning

Al-Mu'tasim was a military man. He was not as interested in intellectual pursuits as his brother al-Ma'mun. But he continued to support writers and scholars. Baghdad remained an important center for learning during his rule.

Some famous scholars during his time included astronomers Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi and Ahmad al-Farghani. There was also the writer al-Jahiz and the mathematician and philosopher al-Kindi. Al-Kindi even dedicated his work On First Philosophy to al-Mu'tasim. Doctors like Salmawayh ibn Bunan and Ibn Masawayh also worked at his court.

Mu'tazilism and the Miḥna

Al-Mu'tasim followed al-Ma'mun's ideas about Mu'tazilism. This was a religious idea that said the Quran was "created" by God. This meant that a God-guided leader could interpret it. Al-Ma'mun made this idea official in 827. In 833, he started an inquisition called the miḥna. This forced people to accept Mu'tazilism.

Al-Mu'tasim actively enforced the miḥna. The chief judge, Ahmad ibn Abi Duwad, was a strong supporter of Mu'tazilism. He was very influential at the caliph's court. Mu'tazilism became linked to al-Mu'tasim's new government. To question it was to question the caliph's authority.

However, many traditionalists strongly opposed Mu'tazilism. They believed the Quran was the literal word of God and could not be changed. The government's efforts to suppress them did not work. When Ahmad ibn Hanbal, a strong opponent, was beaten and imprisoned in 834, it only made him more famous. Later, the strict Hanbali school of thought became very popular.

Campaigns at Home

Al-Mu'tasim was an energetic military leader. He was known as a "warrior-caliph." Most of his military actions were against rebels within the Caliphate. These areas were part of the empire but were not fully under Muslim rule. The three main campaigns were against the Khurramite rebellion, Mazyar, and the Byzantine Empire. These wars also helped al-Mu'tasim gain support from the people.

In 834, an Alid revolt broke out in Khurasan. It was quickly defeated. The leader, Muhammad ibn Qasim, was captured. But he escaped and was never seen again. In the same year, Ujayf ibn 'Anbasa was sent to fight the Zutt. These people lived in the Mesopotamian Marshes and had been rebelling since 820. After seven months, Ujayf defeated them. Many Zutt were sent to the Byzantine border to fight.

The first major campaign of al-Mu'tasim's rule was against the Khurramites in Adharbayjan. This rebellion had been going on since 816. The Khurramites were led by Babak Khorramdin. Al-Ma'mun had mostly left them alone. In 833, al-Mu'tasim sent Ishaq ibn Ibrahim al-Mus'abi to deal with the rebellion. He quickly succeeded. Many Khurramites fled to the Byzantine Empire.

In 835, al-Mu'tasim sent his trusted general, al-Afshin, to fight Babak. After three years, al-Afshin captured Babak in August 837. This ended the rebellion. Babak was brought to Samarra. On January 3, 838, he was paraded on an elephant. Then he was publicly executed.

Soon after, Minkajur al-Ushrusani, a governor appointed by al-Afshin, rebelled. Bugha the Elder marched against him. Minkajur surrendered in 840.

The second major campaign started in 838. It was against Mazyar, the ruler of Tabaristan. Tabaristan had been under Abbasid rule since 760. But its mountainous areas were still ruled by local princes. Mazyar had become the main ruler of Tabaristan. Al-Mu'tasim confirmed his position. But Mazyar refused to report to the Tahirid governor. He insisted on paying taxes directly to al-Mu'tasim. Some say al-Afshin secretly encouraged Mazyar to cause trouble.

Conflict began when Mazyar's troops attacked Muslim cities. They took Muslim settlers prisoner and executed many. The Tahirids invaded Tabaristan. Mazyar was betrayed by his brother, Quhyar. Quhyar also revealed letters between Mazyar and al-Afshin. Mazyar was captured and brought to Samarra. Like Babak, he was paraded and then flogged to death on September 6, 840. After this, the region became more Islamic.

Near the end of al-Mu'tasim's life, there were revolts in Syria. One was led by Abu Harb, also known as "the Veiled One." These revolts showed that some Syrian Arabs still supported the old Umayyad dynasty.

Fighting the Byzantine Empire

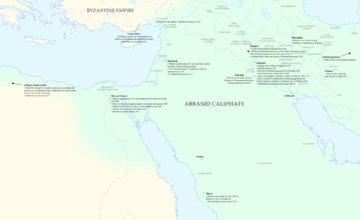

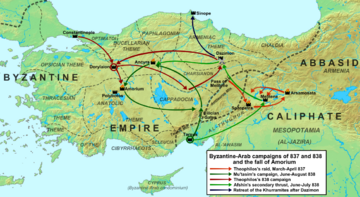

Map of the Byzantine and Abbasid campaigns in the years 837–838, showing Theophilos's raid into Upper Mesopotamia and al-Mu'tasim's retaliatory invasion of Asia Minor, culminating in the conquest of Amorium.

While the Abbasids were busy with the Khurramite rebellion, the Byzantine emperor Theophilos attacked Muslim border areas. He had some success. His army was even joined by about 14,000 Khurramites who had fled to the Byzantine Empire. In 837, Theophilos launched a major campaign. He led a large army into the region around the Euphrates river. The Byzantines captured towns like Zibatra and Arsamosata. They also plundered the countryside.

Refugees arrived in Samarra, telling stories of the brutal raids. The Byzantines had worked with the Khurramites. During the attack on Zibatra, all male prisoners were executed. The rest of the people were sold into slavery. This made the caliph's court very angry.

Al-Mu'tasim personally led the preparations for a revenge attack. Caliphs usually only led wars against Byzantium themselves. He gathered a huge army, possibly 80,000 soldiers. He declared his target to be Amorium, the birthplace of the Byzantine emperor. The caliph even had the city's name painted on his army's shields.

The campaign began in June 838. A smaller force under al-Afshin attacked from the east. Al-Mu'tasim led the main army through the Cilician Gates. Theophilos was surprised by the two-part attack. He tried to fight al-Afshin's smaller force first. But he suffered a big defeat at the Battle of Dazimon on July 22. He barely escaped. A week later, al-Afshin and the main army joined forces. They plundered Ancyra, which was undefended.

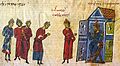

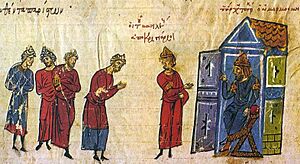

Byzantine envoys before al-Mu'tasim (seated, right), miniature from the Madrid Skylitzes (12th/13th century)

From Ancyra, the Abbasid army moved to Amorium. They started the siege on August 1. The Turkish generals, al-Afshin, Itakh, and Ashinas, took turns attacking the city. The siege was difficult. But the Abbasids found a weak spot in the wall. After two weeks, they stormed the city. Amorium was completely plundered. Its walls were destroyed. Tens of thousands of people were taken away to be sold as slaves.

Al-Mu'tasim considered attacking Constantinople next. But then the plot by his nephew, al-Abbas, was discovered. Al-Mu'tasim had to cut short his campaign. He returned quickly to his lands. The journey back was hard for the army and the prisoners. Many captives died from exhaustion. Some escaped. In response, al-Mu'tasim executed about 6,000 remaining prisoners.

The sack of Amorium brought al-Mu'tasim great fame as a warrior-caliph. It was celebrated by poets. The Abbasids did not continue their success. Raids and counter-raids continued along the border. A truce was agreed in 841. When al-Mu'tasim died in 842, he was planning another large invasion. But his fleet, meant for Constantinople, was destroyed in a storm. After his death, the wars slowed down.

Death and What He Left Behind

Al-Mu'tasim became ill on October 21, 841. His trusted doctor had died the year before. His new doctor's treatment may have made his illness worse. He died on January 5, 842. He had ruled for eight years, eight months, and two days. He was buried in the Jawsaq al-Khaqani palace in Samarra. His son, al-Wathiq, became caliph without any problems. Al-Wathiq's rule continued al-Mu'tasim's policies. The government was still led by the same powerful Turkish generals and officials.

Historians say al-Mu'tasim was kind and generous. He was not as refined as his half-brother. But he was a skilled military commander. He made the caliphate strong both politically and militarily.

Al-Mu'tasim's rule was a turning point for the Abbasid state. His military reforms meant that Arabs lost some control of the empire they had created. The use of military slavery, which he started, became very important in Islamic history. The military became very powerful. It was often made up of minority groups from the edges of the Islamic world. This created a separate ruling class. They were different from the Arab-Iranian majority in their background, language, and sometimes religion. This pattern was copied in many Islamic governments later on.

While al-Mu'tasim's new army was very effective, it also created problems. The soldiers relied completely on their pay. If they didn't get paid, or if their position was threatened, they could become violent. This happened later during the "Anarchy at Samarra" (861–870). The need to pay the military became a constant challenge for the caliphs. This was at a time when government income started to fall. This eventually led to financial problems for the Abbasid government. The caliphs lost much of their political power.

Family Life

Al-Mu'tasim had several wives and concubines. One wife was Badhal. She was known for her musical talent and songwriting. One of his concubines was Qaratis, a Greek woman. She was the mother of his oldest son, al-Wathiq, who became caliph. Another concubine was Shuja. She was from Khwarazm and was the mother of al-Mutawakkil, who also became caliph.

- Children

- Harun, known as al-Wathiq. He was al-Mu'tasim's oldest son.

- Ja'far, known as al-Mutawakkil.

- Muhammad

- Ahmad

- Al-Abbas

- Aisha, who was a poetess.

Al-Mu'tasim in Stories

Al-Mu'tasim appears in the medieval Arabic and Turkish epic Delhemma. This story tells fictional versions of the Arab–Byzantine wars. In it, al-Mu'tasim helps heroes chase a traitor across many countries.

The name al-Mu'tasim is also used for a made-up character. This is in a story called The Approach to al-Mu'tasim. It was written in 1936 by the Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges. The character in the story is not the real caliph. But Borges mentions the real al-Mu'tasim. He says the caliph "was victorious in eight battles, fathered eight sons and eight daughters, left eight thousand slaves, and ruled for a period of eight years, eight moons, and eight days."

This quote from Borges is not perfectly accurate. But it is based on what the historian al-Tabari wrote. Al-Tabari noted that al-Mu'tasim was "born in the eighth month, was the eighth caliph, in the eighth generation from al-Abbas, his lifespan was eight and forty years, that he died leaving eight sons and eight daughters, and that he reigned for eight years and eight months." This shows why al-Mu'tasim was often called al-Muthamman ("the man of eight") in Arabic writings.

Images for kids

-

Gold dinar of al-Mu'tasim, minted in Baghdad in 839

-

Map of the Muslim expansion during the 7th and 8th centuries and of the Muslim world under the Umayyad and early Abbasid caliphates, from the Allgemeiner historischer Handatlas of Gustav Droysen (1886)

-

Silver dirham of al-Mu'tasim, minted at al-Muhammadiya in 836/7

-

Map of the Byzantine and Abbasid campaigns in the years 837–838, showing Theophilos's raid into Upper Mesopotamia and al-Mu'tasim's retaliatory invasion of Asia Minor, culminating in the conquest of Amorium.

-

Byzantine envoys before al-Mu'tasim (seated, right), miniature from the Madrid Skylitzes (12th/13th century)

See also

In Spanish: Al-Mutásim para niños

In Spanish: Al-Mutásim para niños