Egypt in the Middle Ages facts for kids

After the Islamic armies took control of Egypt in 639 AD, the country was first ruled by governors. These governors acted on behalf of the Rashidun and then the Umayyad leaders in Damascus. In 747 AD, the Umayyads were overthrown. During this time, the city of Askar became the capital and the center of government. Egypt was divided into two main regions, Upper and Lower Egypt, both controlled by the military under one governor.

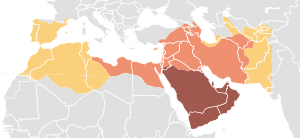

From 639 AD until the early 1500s, many different ruling families, called dynasties, controlled Egypt. The Umayyad period lasted from 658 to 750 AD. After them came the Abbasids, who focused more on collecting taxes and centralizing power. In 868 AD, the Tulunids, led by Ahmad ibn Tulun, expanded Egypt's territory into the area known today as the Levant. He ruled until 884 AD. After some difficult years under his successor, many people returned their loyalty to the Abbasids, who took back power from the Tulunids in 904 AD. In 969 AD, Egypt came under the control of the Fatimids. This dynasty began to weaken after their last ruler died in 1171 AD.

In 1174 AD, the Ayyubids took over Egypt. They ruled from Damascus, not from Cairo. This dynasty fought against the Crusader States during the Fifth Crusade. The Ayyubid Sultan Najm al-Din recaptured Jerusalem in 1244 AD. He brought in special soldiers called Mamluks to help fight the Crusaders. This decision eventually led to the Ayyubids being overthrown by these very bodyguards, the Mamluks, in 1252 AD. The Mamluks ruled until 1517 AD, when Egypt became part of the Ottoman Empire.

Contents

Early Islamic Rule in Egypt

How Muslims Conquered Egypt

In 639 AD, the second Islamic leader, Umar, sent an army of about 4,000 soldiers to Egypt. This army was led by Amr ibn al-As. In 640 AD, another 5,000 soldiers joined them. They defeated a Byzantine army at the battle of Heliopolis. Amr then moved towards Alexandria, which surrendered to him in November 641 AD.

The Byzantines briefly took Alexandria back in 645 AD, but Amr recaptured it in 646 AD. In 654 AD, a Byzantine invasion fleet was pushed back. After this, the Byzantines did not try seriously to take Egypt back.

How Early Islamic Egypt Was Governed

After Alexandria first surrendered, Amr chose a new place for his soldiers to live. This was near the Byzantine fortress of Babylon. The new settlement was named Fustat, after Amr's tent, which had been set up there. Fustat quickly became the main city of Islamic Egypt. It was the capital and home for the government for a long time.

After the conquest, Egypt was first divided into two regions: Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt (which included the Nile Delta). However, in 643/4 AD, the leader Uthman appointed one governor for all of Egypt, who lived in Fustat. This governor then chose assistants for Upper and Lower Egypt. Alexandria remained a special area because it protected the country from Byzantine attacks and was a major naval base. It was like a border fort with many soldiers.

The main power of early Muslim rule came from the army, called the jund. These were Arab settlers who had followed Amr during the conquest. Most of them came from southern Arab tribes. They controlled Egypt's affairs for the first two centuries of Muslim rule. At first, there were 15,500 soldiers, but their numbers grew to 40,000 by the time of Caliph Mu'awiya I (661–680 AD). These soldiers received an annual payment and were very protective of their privileges.

In exchange for a small tax and food for the troops, the Christian people of Egypt were not required to serve in the military. They were also free to practice their religion and manage their own community affairs.

At first, not many Copts (Egyptian Christians) converted to Islam. The old tax system stayed in place for most of the first Islamic century. The country's old divisions into districts were kept. The governor of Egypt would send demands directly to these districts. The head of the community, usually a Copt but sometimes a Muslim Egyptian, was responsible for making sure these demands were met.

The Umayyad Period

During a civil war called the First Fitna, Caliph Ali (656–661 AD) appointed Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr as governor of Egypt. But Amr led an invasion in 658 AD, defeated Ibn Abi Bakr, and secured Egypt for the Umayyads. Amr then served as governor until he died in 664 AD.

From 667/8 to 682 AD, another strong supporter of the Umayyads, Maslama ibn Mukhallad al-Ansari, governed the province. During another civil war, Ibn al-Zubayr gained support in Egypt and sent his own governor. However, the local Arabs did not like this new rule and asked the Umayyad caliph Marwan I (684–685 AD) for help. In December 684 AD, Marwan easily took back Egypt. Marwan made his son Abd al-Aziz the governor. Abd al-Aziz ruled Egypt for 20 years, almost like an independent ruler, thanks to his strong ties with the army. He also oversaw the completion of the Muslim conquest of North Africa. When he died, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (685–695 AD) sent his own son, Abdallah, to govern. This was to regain control and stop Egypt from becoming a family kingdom.

In 715 AD, Abd al-Malik ibn Rifa'a al-Fahmi became governor, followed by Ayyub ibn Sharhabil in 717 AD. These were the first governors not from the Umayyad family. They reportedly put more pressure on the Copts and started efforts to spread Islam. The Copts' anger over taxes led to a revolt in 725 AD. In 727 AD, to increase the Arab population, 3,000 Arabs settled near Bilbeis. Meanwhile, the Arabic language was becoming more common, and in 706 AD, it became the official language of the government. This is when Egyptian Arabic, the modern dialect of Egypt, began to form. More Coptic revolts happened in 739 and 750 AD, the last year of Umayyad rule. These revolts were always due to increased taxes.

The Abbasid Period

The Abbasid period brought new taxes, and the Copts revolted again in the fourth year of Abbasid rule. In the early 800s, Egypt was again ruled by a governor, Abdallah ibn Tahir, who chose to live in Baghdad and sent a deputy to govern Egypt for him. In 828 AD, another Egyptian revolt broke out, and in 831 AD, Copts joined with local Muslims against the government.

A big change happened in 834 AD. Caliph al-Mu'tasim stopped paying the local Arab army (the jund) from Egypt's taxes. He removed the Arab families from the army lists and ordered that all of Egypt's money be sent to the central government. The government would then pay only the Turkish soldiers stationed in Egypt. This move helped the central government gain more power. It also meant the old Arab elites lost influence, and power shifted to Turkish soldiers favored by al-Mu'tasim.

Around the same time, the Muslim population in Egypt began to outnumber the Coptic Christians. Throughout the 800s, rural areas became more Arab and Islamic. This process was very fast, especially in Upper Egypt, partly due to new settlers after gold and emerald mines were found at Aswan. However, Upper Egypt was only loosely controlled by the local governor. Also, constant fighting and problems within the Abbasid government led to new revolutionary movements in Egypt in the 870s. These movements showed that many Egyptians were unhappy with being ruled by Baghdad. This feeling would later lead many Egyptians to support the Fatimids in the 900s.

The Tulunid Period

In 868 AD, Caliph al-Mu'tazz (866–869 AD) put the Turkish general Bakbak in charge of Egypt. Bakbak then sent his stepson Ahmad ibn Tulun to be his lieutenant and governor. This started a new chapter in Egypt's history. Before, Egypt was just a province of a larger empire. Under Ibn Tulun, it became an independent political center. Ibn Tulun used Egypt's wealth to expand his rule into the Levant, a region that includes modern-day Syria and Lebanon. Later Egyptian rulers, like the Ikhshidids and the Mamluks, followed this pattern.

Ibn Tulun's first years as governor were spent fighting for power with Ibn al-Mudabbir, a powerful financial official. Ibn al-Mudabbir had been in charge of taxes since about 861 AD and was very unpopular because he doubled taxes and added new ones for both Muslims and non-Muslims. By 872 AD, Ibn Tulun managed to get Ibn al-Mudabbir fired and took control of the finances himself. He also built his own army, which made him almost independent from Baghdad.

To show his power, Ibn Tulun built a new palace city called al-Qata'i in 870 AD, northeast of Fustat. This city was meant to be like the Abbasid capital, Samarra. It had areas for his army's regiments, a horse track, a hospital, and palaces. The most important building in the new city was the Mosque of Ibn Tulun. Ibn Tulun also set up his government like Samarra's, creating new departments and hiring officials trained there. His rule was based on a strong army of slave soldiers, and paying these soldiers was a major concern for the government.

Because of the need for more money, in 879 AD, the finances were put under Abu Bakr Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Madhara'i. His family, the al-Madhara'i dynasty, controlled Egypt's financial system for the next 70 years. Ibn Tulun's rule brought peace and safety, an efficient government, and improvements to the irrigation system. Along with consistently high Nile floods, this led to a big increase in wealth. By the end of his rule, Ibn Tulun had saved ten million dinars (gold coins).

Ibn Tulun became powerful because the Abbasid government was weak. It was threatened by other groups and by a rebellion in Iraq. There was also a rivalry between Caliph al-Mu'tamid (870–892 AD) and his powerful brother, al-Muwaffaq. Open conflict between Ibn Tulun and al-Muwaffaq started in 875/6 AD. Al-Muwaffaq tried to remove Ibn Tulun from Egypt, but his army barely reached Syria. In response, with the Caliph's support, Ibn Tulun gained control of all of Syria and the border areas in 877/8 AD.

Ibn Tulun took over Syria but failed to capture Tarsus. He had to return to Egypt because his oldest son, Abbas, started a revolt. Ibn Tulun imprisoned Abbas and named his second son, Khumarawayh, as his heir. In 882 AD, Ibn Tulun almost made Egypt the new center of the Caliphate when al-Mu'tamid tried to flee to his lands. However, the Caliph was caught and brought back to Samarra in February 883 AD, back under his brother's control. This created new tension between Ibn Tulun and al-Muwaffaq. Ibn Tulun gathered religious scholars in Damascus who declared al-Muwaffaq a usurper, condemned his treatment of the Caliph, and called for a holy war (jihād) against him. Al-Muwaffaq was condemned in sermons in mosques across Tulunid lands, and the Abbasid regent responded by condemning Ibn Tulun. Ibn Tulun tried again to take Tarsus but failed. He fell ill on his way back to Egypt and died in Fustat on May 10, 884 AD.

When Ibn Tulun died, Khumarawayh became the new ruler without any problems, supported by the Tulunid leaders. Ibn Tulun left his son a strong army, a stable economy, and experienced commanders. Khumarawayh managed to keep his power against the Abbasids' attempt to overthrow him at the Battle of Tawahin. He even gained more land, which was recognized in a treaty with al-Muwaffaq in 886 AD. This treaty gave the Tulunids hereditary rule over Egypt and Syria for 30 years. When al-Muwaffaq's son al-Mu'tadid became Caliph in 892 AD, there was a new agreement. This led to Khumarawayh's daughter marrying the new Caliph, but also meant some provinces returned to Abbasid control.

At home, Khumarawayh's rule was known for "luxury and decay," but also for a time of peace in Egypt and Syria, which was rare then. However, Khumarawayh's expensive spending emptied the treasury. By the time he was killed in 896 AD, the Tulunid treasury was empty. After Khumarawayh's death, internal fighting weakened the Tulunid power. Khumarawayh's son Jaysh was a drunkard who killed his uncle. He was removed from power after only a few months and replaced by his brother Harun ibn Khumarawayh. Harun was also a weak ruler. Although a revolt by his uncle Rabi'ah in Alexandria was stopped, the Tulunids could not fight off attacks from the Qarmatians who started raiding at the same time. Also, many commanders left and joined the Abbasids, whose power was growing again under Caliph al-Mu'tadid (892–902 AD).

Finally, in December 904 AD, two other sons of Ibn Tulun, Ali and Shayban, killed their nephew and took control of the Tulunid state. This event did not stop the decline. It made key commanders in Syria angry and led to the quick and easy reconquest of Syria and Egypt by the Abbasids under Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Katib. He entered Fustat in January 905 AD. Except for the Great Mosque of Ibn Tulun, the victorious Abbasid troops looted al-Qata'i and destroyed it.

Second Abbasid and Ikhshidid Periods

The Abbasids successfully fought off Fatimid invasions of Egypt in 914–915 and 919–921 AD.

In 935 AD, after stopping another Fatimid attack, the Turkish commander Muhammad ibn Tughj became the actual ruler of Egypt. He was given the title al-Ikhshid. After he died in 946 AD, his son Unujur took over peacefully. This was mainly due to the strong influence of the skilled commander-in-chief, Kafur. Kafur was one of the many Black African slaves recruited by al-Ikhshid. He remained the most important minister and virtual ruler of Egypt for the next 22 years, taking power himself in 966 AD until his death two years later. After his death, in 969 AD, the Fatimids invaded and conquered Egypt, starting a new era for the country.

The Fatimid Period

Jawhar as-Siqilli immediately began building a new city, Cairo, to house the army he brought. A palace for the Caliph and a mosque for the army were built quickly. For many centuries, these remained important centers of Muslim learning. However, the Carmathians from Damascus attacked, and in the autumn of 971 AD, Jawhar found himself surrounded in his new city. By a clever attack and by bribing some Carmathian officers, Jawhar managed to defeat the attackers. They were forced to leave Egypt and part of Syria.

Meanwhile, the caliph al-Muizz was called to move into the palace built for him. After leaving a deputy to manage his western lands, he arrived in Alexandria on May 31, 973 AD. He then began teaching his new subjects about the specific form of Islam (Shiism) his family followed. Since this was similar to what the Carmathians believed, he hoped to get their leader to surrender through discussion. But this plan failed, and there was a new invasion from the Carmathians the year after he arrived. The caliph found himself surrounded in his capital again.

The Carmathians were slowly forced to retreat from Egypt and then from Syria. This happened through successful battles and by using bribes to cause disagreements among their leaders. Al-Muizz also took action against the Byzantines, with whom his generals fought in Syria with mixed results. Before he died, he was recognized as Caliph in Mecca and Medina, as well as Syria, Egypt, and North Africa all the way to Tangier.

Under the vizier al-Aziz, there was a lot of tolerance for other Islamic groups and other communities. However, the belief that Egyptian Christians were working with the Byzantine emperor and even burned a fleet being built for the Byzantine war led to some persecution. Al-Aziz tried, but failed, to become friends with the Buwayhid ruler of Baghdad. He also tried to take Aleppo, which was key to Iraq, but the Byzantines stopped him. His North African lands were kept and expanded, but the Fatimid caliph's power in that region was mostly just on paper.

His successor al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah became ruler at the age of eleven. He was the son of Aziz and a Christian mother. He ruled strongly and successfully, and he made peace with the Byzantine emperor. He is perhaps best remembered for destroying the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem in 1009 AD. This action helped cause the Crusades. However, it was part of a larger plan to force all Christians and Jews in his lands to adopt his beliefs.

A more positive way to achieve this goal was building a large library in Cairo, with plenty of resources for students. This library was modeled after a similar one in Baghdad. For unknown reasons, al-Hakim disappeared in 1021 AD.

In 1049 AD, the Zirid dynasty in North Africa returned to the Sunni faith and became subjects of the Caliphate in Baghdad. But at the same time, Yemen recognized the Fatimid caliphate. Meanwhile, Baghdad was taken by the Turks, falling to the Seljuk leader Tughrul Beg in 1059 AD. The Turks also looted Cairo in 1068 AD, but they were driven out by 1074 AD. During this time, however, Syria was taken over by an invader connected to the Seljuk leader Malik Shah, and Damascus was permanently lost to the Fatimids. This period is also remembered for the rise of the Hashshashin, or Assassins.

During the Crusades, al-Mustafa stayed in Alexandria. He helped the Crusaders by taking Jerusalem from the Ortokids, which made it easier for the Crusaders to conquer it in 1099 AD. He tried to fix his mistake by advancing into Palestine himself, but he was defeated at the battle of Ascalon and forced to return to Egypt. Many of the Fatimids' lands in Palestine then fell to the Crusaders.

In 1118 AD, Egypt was invaded by Baldwin I of Jerusalem, who burned gates and mosques in Farama and advanced to Tinnis. He was forced to retreat due to illness. In August 1121 AD, al-Afdal Shahanshah was killed in Cairo. It is said the Caliph was involved and immediately looted his house, where amazing treasures were supposedly kept. The vizier's (chief minister's) job was given to al-Mamn. His foreign policy was not successful. He lost Tyre to the Crusaders, and a fleet he prepared was defeated by the Venetians.

In 1153 AD, Ascalon was lost. This was the last place the Fatimids held in Syria. Its loss was blamed on disagreements among the soldiers defending it. In April 1154 AD, Caliph al-Zafir was murdered by his vizier Abbas. This was followed by a massacre of Zafir's brothers, and his infant son Abul-Qasim Isa was put on the throne.

In December 1162 AD, the vizier Shawar took control of Cairo. However, after only nine months, he was forced to flee to Damascus. There, he was welcomed by Prince Nureddin, who sent a force of Kurds with him to Cairo, led by Asad al-din Shirkuh. At the same time, Egypt was invaded by the Franks, who raided and caused much damage on the coast. Shawar recaptured Cairo, but then a dispute arose with his Syrian allies over who would control Egypt. Shawar, unable to deal with the Syrians, asked for help from the Frankish king of Jerusalem Amalric I. Amalric quickly came to his aid with a large force. They joined Shawar's army and surrounded Shirkuh in Bilbeis for three months. At the end of this time, because Nureddin was having successes in Syria, the Franks allowed Shirkuh and his troops to return to Syria freely, on condition that Egypt be left alone (October 1164 AD).

Two years later, Shirkuh, a Kurdish general known as "the Lion," convinced Nureddin to let him lead another expedition to Egypt. This army left Syria in January 1167 AD. A Frankish army quickly came to Shawar's aid. At the battle of Babain (April 11, 1167 AD), the allies were defeated by the forces led by Shirkuh and his nephew Saladin. Saladin was made governor of Alexandria, which surrendered to Shirkuh without a fight. In 1168 AD, Amalric invaded again, but Shirkuh's return made the Crusaders withdraw.

Shirkuh was appointed vizier but died soon after (March 23, 1169 AD). The Caliph appointed Saladin as Shirkuh's successor. The new vizier claimed to hold office as Nureddin's deputy. Nureddin faithfully helped his deputy deal with Crusader invasions of Egypt. He ordered Saladin to replace the Fatimid caliph's name with the Abbasid caliph's name in public worship. The last Fatimid caliph died soon after, in September 1171 AD.

The Ayyubid Period

Saladin, a general known as "the Lion," was confirmed as Nureddin's deputy in Egypt. When Nureddin died on April 12, 1174 AD, Saladin took the title of sultan. During his rule, Damascus, not Cairo, was the main city of the empire. However, he fortified Cairo, which became the political center of Egypt. By 1183 AD, Saladin's rule over Egypt and North Syria was firmly established. Saladin spent much of his time in Syria, fighting the Crusader States. Egypt was mostly governed by his deputy Karaksh.

Saladin's son Othman took over in Egypt in 1193 AD. He teamed up with his uncle (Saladin's brother) Al-Adil I against Saladin's other sons. After the wars that followed, Al-Adil took power in 1200 AD. He died in 1218 AD during the siege of Damietta in the Fifth Crusade. His successor, Al-Kamil, lost Damietta to the Crusaders in 1219 AD. However, he stopped their advance to Cairo by flooding the Nile, forcing them to leave Egypt in 1221 AD. Al-Kamil was later forced to give up various cities in Palestine and Syria to Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor during the Sixth Crusade. He did this to get Frederick's help against Damascus.

Najm al-Din became sultan in 1240 AD. During his rule, Jerusalem was recaptured in 1244 AD. He also brought a larger force of Mameluks into the army. He spent much of his time fighting in Syria, where he allied with the Khwarezmians against the Crusaders and other Ayyubids. In 1249 AD, he faced an invasion by Louis IX of France (the Seventh Crusade), and Damietta was lost again. Najm al-Din died soon after this. But his son Turanshah defeated Louis and drove the Crusaders out of Egypt. Turanshah was soon overthrown by the Mamluks. They had become the "kingmakers" since their arrival and now wanted full power for themselves.

Mamluk Egypt

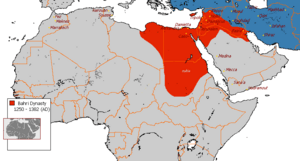

The Mamluks' strong way of gaining power brought them great political and economic success. This led them to become the rulers of Egypt. The Mamluk period in Egypt started with the Bahri Dynasty, followed by the Burji Dynasty. The Bahri Dynasty ruled from 1250 to 1382 AD, and the Burji dynasty lasted from 1382 to 1517 AD.

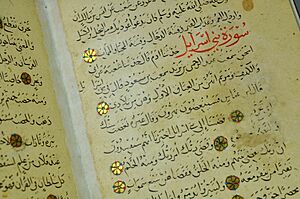

The Mamluk Empire made important cultural contributions beyond religion. Literature and astronomy were two subjects they valued and studied deeply. They were a very educated society. Private libraries were a sign of wealth and status in Mamluk culture. Some discovered libraries show signs of having thousands of books.

This period ended due to famine, military problems, diseases like the Black Death, and high taxes.

The Bahri Dynasty

The Mamluk sultans were chosen from freed slaves who were part of the court and became slave owners themselves. They also held positions in the army. The sultans often could not create a lasting family rule. They usually left behind young children who were then overthrown. The Bahri dynasty (1250–1382 AD) had 25 sultans in its 132-year period. Many died or were killed shortly after taking power; very few ruled for more than a few years. The first of these was Aybak, who married Shajar al-Durr (the widow of al-Salih Ayyub) and quickly started a war with the region of present-day Syria. He was killed in 1257 AD and was followed by Qutuz, who faced a growing danger from the Mongols.

Qutuz defeated the army of Hulagu Khan at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260 AD. This allowed him to take back all of Syria except for the Crusader strongholds. On the way back to Egypt after the battle, Qutuz died. He was succeeded by another commander, Baybars, who became sultan and ruled from 1260 to 1277 AD. In 1291 AD, al-Ashraf Khalil captured Acre, the last of the Crusader cities. The Bahris greatly increased Egypt's power and fame. They built Cairo from a small town into one of the most important cities in the world.

Because Baghdad was destroyed by the Mongols in 1258 AD, Cairo became the central city of the Islamic world. The Mamluks built much of Cairo's oldest surviving architecture, including many mosques made of stone with tall, impressive designs.

Starting in 1347 AD, the Egyptian population, economy, and political system suffered greatly from the Black Death pandemic. Waves of this disease continued to devastate Egypt until the early 1500s.

In 1377 AD, a revolt in Syria spread to Egypt. The government was taken over by the Circassians Berekeh and Barkuk. Barkuk was declared sultan in 1382 AD, ending the Bahri dynasty. He was expelled in 1389 AD but recaptured Cairo in 1390 AD, starting the Burji dynasty.

The Burji Dynasty

The Burji dynasty (1382–1517 AD) was very unstable, with political power struggles leading to sultans ruling for only short periods. During this time, the Mamluks fought Timur Lenk and conquered Cyprus.

Plague epidemics continued to harm Egypt when they spread across the region in 1388–1389, 1397–1398, 1403–1407, 1410–1411, 1415–1419, 1429–1430, 1438–1439, 1444–1449, 1455, 1459–1460, 1468–1469, 1476–1477, 1492, 1498, 1504–1505, and 1513–1514 AD.

Constant political arguments made it hard for them to resist the Ottomans. This led to Egypt becoming a vassal state under Ottoman Sultan Selim I. The sultan defeated the Mamluks and captured Cairo on January 20, 1517 AD. This moved the center of power to Istanbul. However, the Ottoman Empire kept the Mamluks as the ruling class in Egypt. The Mamluks and the Burji family regained much of their influence, but they were technically still under Ottoman rule. Egypt then entered the middle period of the Ottoman Empire.

|

See also

Sources

- Athamina, Khalil (1997). [Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books "Some Administrative, Military, and Socio-Political Aspects of Early Muslim Egypt"]. In Lev, Yaacov. War and Society in the Eastern Mediterranean: 7th–15th Centuries. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 101–114. ISBN 90-04-10032-6. Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books.

- Bianquis, Thierry (1998). [Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books "Autonomous Egypt from Ibn Ṭūlūn to Kāfūr, 868–969"]. In Petry, Carl F.. Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume One: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–119. ISBN 0-521-47137-0. Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books.

- Bonner, Michael (2010). "The waning of empire, 861–945". In Robinson, Chase F.. The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 305–359. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Brett, Michael (2001). [Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books The Rise of the Fatimids: The World of the Mediterranean and the Middle East in the Fourth Century of the Hijra, Tenth Century CE]. The Medieval Mediterranean. 30. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11741-5. Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books.

- Brett, Michael (2010). "Egypt". In Robinson, Chase F.. The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 506–540. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Halm, Heinz (1996). [Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books The Empire of the Mahdi: The Rise of the Fatimids]. Handbook of Oriental Studies. 26. transl. by Michael Bonner. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10056-3. Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1998). [Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books "Egypt as a province in the Islamic caliphate, 641–868"]. In Petry, Carl F.. Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume One: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–85. ISBN 0-521-47137-0. Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). [Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century] (2nd ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd.. ISBN 0-582-40525-4. Egypt in the Middle Ages at Google Books.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |