Egypt in World War II facts for kids

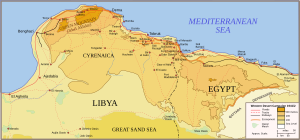

Egypt was a very important place during World War Two. It was where the big North African campaign battles happened, including the famous First and Second Battles of El Alamein. Even though Egypt had been an independent kingdom since 1922, and shared control of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan with Britain, the United Kingdom still had a lot of power over it. This strong British influence started way back in 1882, when Britain helped Egypt's ruler, Tawfik Pasha, during the Orabi Revolt and then stayed in the country.

Many Egyptians were unhappy about Britain's control, especially how Britain tried to keep Egypt out of managing Sudan. Because of this, even though thousands of British soldiers were in Egypt (as agreed in the 1936 treaty), Egypt officially stayed neutral during the war. It only declared war on the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, Japan) in early 1945. Egypt didn't have its government overthrown like Iraq or Iran did by the British. But Egypt did experience the Abdeen Palace Incident in 1942. This was a tense moment between Egypt's King Farouk and the British military. What happened then helped lead to the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 ten years later.

Contents

Egypt's Story in World War Two

Before the Big War

For most of the 1800s, Egypt was almost independent, even though it was technically part of the Ottoman Empire. It had its own rulers, called pashas, and was growing its lands in East Africa, especially Sudan. But the United Kingdom slowly became the most powerful foreign country in Egypt and Sudan.

In 1875, Egypt's ruler, Isma'il the Magnificent, had money problems. He sold Egypt's shares in the Suez Canal Company to the British government. The Suez Canal was a super important waterway for Britain, connecting it to its huge empire in India. Controlling the Canal became the main reason Britain wanted to control Egypt.

A few years later, in 1879, Britain and other powerful countries removed Isma'il and put his son Tewfik in charge. After a nationalist uprising led by an officer named Ahmed Urabi, Britain invaded in 1882, saying they were bringing stability. After the revolt was crushed, Britain became the real ruler of Egypt. A British official named Evelyn Baring managed Egypt's money. Britain also pushed Egypt to join World War One against the Ottoman Empire.

After World War One, a group of Egyptian nationalists, led by Sa'ad Zaghoul, asked for Egypt to be independent at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Britain tried to stop this by arresting the leaders. This caused huge protests, known as the Egyptian Revolution of 1919. In 1922, the United Kingdom officially said Egypt was an independent country.

Sa'ad Zaghoul's group, called the Wafd (meaning "delegation" in Arabic), became the most popular political party under Egypt's 1923 constitution. This constitution created a parliament elected by the people. However, the king still had a lot of power. He could choose the prime minister and close down parliament.

Britain also kept control over certain things in Egypt. These included foreign policy, where British soldiers could be stationed to defend Egypt and the Suez Canal, and how Sudan was run. These issues made Egyptian nationalists very angry, and they kept trying to get more independence for Egypt.

Egyptian politics at this time had three main groups fighting for power: the conservative palace (the King), the liberal Wafd Party, and the British. Each group wanted to control the others. The British wanted to avoid another revolution while keeping their influence. The King and his allies wanted to keep a strong Islamic monarchy.

The 1936 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty

When Italy invaded Ethiopia, Britain felt its position in Egypt was at risk. Egypt was the only country between Italian Libya and Italian East Africa. So, in 1936, Britain and Egypt signed a new agreement called the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty.

This treaty said that British troops in Egypt would mostly stay near the Suez Canal until 1956. They could also be in Alexandria until 1944. But if there was a war, Britain could send more soldiers to Egypt. Egypt also had to help Britain with supplies and other support if there was a war, but it didn't have to fight for Britain. This treaty gave Britain the right to fight World War Two on Egyptian land, while Egypt could officially stay neutral.

Egypt's Government During the War

Ali Maher's Time as Prime Minister

When World War Two started, power in Egypt was split between King Farouk and the parliament, led by Prime Minister Ali Maher Pasha. Maher was from a conservative party that was against the Wafd.

At first, Maher followed the treaty. The Egyptian government cut ties with Germany, took over German property, and held German citizens. But the government didn't want to declare war on Germany. Many Egyptians saw the war as a European problem that didn't involve them. King Farouk also wanted Egypt to stay neutral. He didn't like Britain's strong control over Egypt. When British soldiers returned to Egyptian streets, it made many Egyptians even more against Britain.

Maher's refusal to declare war on Italy after the Italian invasion of Egypt made Britain even more frustrated. Even though Egypt and Italy broke off relations, Egypt's government still wouldn't declare war. Britain also wanted King Farouk to send away or hold all Italians in Egypt, including those who worked for the King. There's a story that Farouk told the British Ambassador, Sir Miles Lampson: "I'll get rid of my Italians when you get rid of yours." This was a jab at the ambassador's Italian wife.

The Egyptian government wasn't trying to stay neutral because it liked the Axis powers. It was more about the power struggle between Egyptian nationalists and British influence. The 1936 treaty didn't force Egypt to declare war on Britain's enemies. Many Egyptians saw the fighting with Italy as just border problems that would only weaken the British. They didn't feel like fighting for the British colonial empire.

Lampson was very angry about this. In 1940, he demanded that Egyptian troops leave the Western Desert, that Egypt pay for Britain to defend it, and that Egypt's army chief, Aziz Ali al-Misri, be removed for possibly supporting the Axis. They reached a compromise: General Henry Maitland Wilson would command Egyptian forces in the Western Desert, and al-Misri was removed.

Hassan Sabry's Time as Prime Minister

After Maher had to resign because of British pressure, Hassan Sabry became prime minister. He led a group of parties that were against the Wafd. His government got two important things from Britain. First, Britain ended the Caisse de la Dette Publique, which was a group that made Egypt pay its debts to European countries. Second, Britain agreed to buy Egyptian cotton to help the industry, since trade with Europe was stopped. In return, Egypt agreed to work with the British forces, supplying their troops and giving them millions of dollars every year. So, even without declaring war, Britain found a way for Egypt to support them without direct military involvement. This cooperation would have continued, but Sabry died in November 1940.

Hussein Sirri Pasha's Time as Prime Minister

With Lampson's suggestion, Hussein Sirri Pasha quickly became prime minister. Sirri promised to continue policies that favored Britain in parliament. But Egyptian politics at the time were very difficult for him. He was too conservative to work with the Wafd, and too pro-British to work with King Farouk, who liked Italy. So, his government relied on a weak group of different parties.

During his time, Egypt faced big problems like a higher cost of living and not enough food. The Wafd, led by the experienced politician Mostafa el-Nahhas Pasha, saw this as their chance to get back in power. They demanded an end to the shared control of Sudan with Britain and that all British forces leave Egypt after the war. The Wafd blamed the British presence for the people's declining living conditions, and Egyptians protested.

On January 6, 1942, Egypt cut ties with Vichy France, which was a puppet government controlled by Nazi Germany. This made King Farouk angry because he wasn't asked about the decision. A big argument started about whether the king needed to be consulted on foreign relations. Sirri agreed to resign on February 1, but the problem quickly got worse.

The Abdeen Palace Incident

On February 2, the British Ambassador Lampson demanded that King Farouk work with the Wafd leader Nahhas to form a new government. Lampson believed that the Wafd, with their democratic ideas and popularity, would be the strongest ally for Britain. However, Nahhas refused to join a coalition government, knowing it would limit his power.

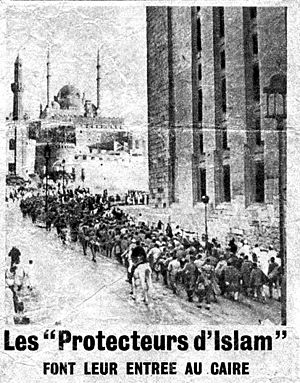

On February 4, Lampson threatened Farouk. He said, "Unless I hear by 6 P.M. today that Nahas has been asked to form a Government His Majesty King Farouk must accept the consequences." Egypt's response was to condemn Britain for interfering in its internal affairs. At 9 P.M., Lampson arrived at Abdeen Palace with British soldiers and tanks. He threatened the King that his palace would be bombed, and he would be forced to give up his throne and leave Egypt, unless he agreed to the British demands. This was a serious threat. Britain had already invaded Iraq and overthrown the government of Iran to put pro-Allied governments in power. After Lampson ordered Farouk to sign a paper giving up his throne, Farouk offered to call Nahhas to form a government. Lampson agreed to a Wafd government led by Nahhas.

Mohamed Naguib, a respected military officer who would later help lead the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, asked Farouk to fight the British. He promised that loyal officers would defend the palace. This incident was a huge personal insult to Farouk and a national humiliation for Egypt. Gamal Abdel Nasser, who was a young military officer at the time and later led the 1952 Revolution with Mohamed Naguib, said the incident was a clear attack on Egypt's independence. He wrote: "I am ashamed that our army has not reacted against this attack," and wished for "calamity" to happen to the British.

Mostafa El-Nahas' Time as Prime Minister

Elections were held in March, and the Wafd won most of the seats (203 out of 264) because other parties boycotted the election. Ali Maher was arrested in April.

The finance minister, Makram Ebied Pasha, left the Wafd Party. He called the agreement between Nahhas and Lampson a "second treaty" and complained about corruption in the government. After he was removed, he spent the next year writing a book called Black Book. This book showed a lot of corruption in the government, especially involving Nahhas and his wife. This was a big blow to the government and ruined the friendship between Nahhas and Ebied, who were founders of the Wafd party and had been part of the 1919 revolution. Nahhas' reputation as the leader of the revolution after Sa'ad Zaghoul was badly damaged. Ebied and 26 Wafdist politicians who supported him even formed a rival party. Because of his writings, Ebied was arrested on May 9, 1944, and stayed in prison until Nahhas was no longer prime minister.

During Nahhas' time as prime minister, Egypt hosted two important Allied World War Two conferences in its capital, Cairo. The First Cairo Conference planned how to fight back against Japan. They also announced the Cairo Declaration, saying that the Allies wanted Japan to surrender completely. The Second Cairo Conference talked about whether Turkey might join the war against Germany, but it was decided Turkey would stay neutral. Egypt also hosted the Alexandria Protocol, an agreement between five Arab countries (Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen, and Syria) to form a joint Arab Organization. This led to the creation of the League of Arab States the next year.

By 1944, World War Two in North Africa was over. King Farouk saw this as his chance to get rid of Nahhas and the Wafd. The Wafd's image as the nationalist group fighting the British had been damaged. Even though Lampson saw the Wafd as an ally against the young King, he knew the government had lost its support. After Nahhas went on a tour of Egypt, Farouk claimed that Nahhas was acting like a king, saying that "there could not be two kings of Egypt." Lampson joked, "God forbid. We have found that one is quite enough." The relationship between the king and Nahhas was broken. On October 6, 1944, Nahhas was dismissed, and Ali Maher and Ebied were released from prison.

Ahmed Maher's Time as Prime Minister

Ahmed Maher, the leader of the Sa'adists (a party made up of former Wafd members), formed a new government. The now-freed Ebied returned as Minister of Finance. The 1945 elections, which the Wafd boycotted, were a victory for parties against the Wafd.

In Europe, it was clear that Germany was going to lose the war. So, politicians started thinking about the future after the war. The countries that fought the Axis formed the United Nations, a huge international organization. It was clear that Egypt would not be part of the UN if it didn't join the war. On February 24, 1945, Egypt declared war on Germany and Japan. Afterwards, as Maher walked through the halls of parliament, he was killed by an Egyptian nationalist who was furious about this "giving in" to British influence. Egypt officially joined the United Nations on October 24, 1945.

Egypt After the War

The war was a very important time in Egyptian history. It was the first time an Egyptian prime minister had been killed since 1910. This started a wave of killings after the war, including former finance minister Amin Osman, prime minister Norashy Pasha, and Hasan al-Banna, the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Egypt's help in the war brought back old arguments about Sudan, British soldiers in Egypt, and the Suez Canal. At the same time, American interest and involvement in Egypt grew, showing that the old British power was ending. The war, especially the 1942 Abdeen Palace incident, showed Egyptians that neither the king nor the Wafd could truly challenge British influence. Egyptian nationalism grew even stronger. The 1936 treaty with Britain was canceled in 1951. The huge gap between rich and poor led to more anger towards the government. Egypt's old system of government collapsed during the 1952 revolution, just seven years after the war ended.

Egyptian Public Opinion

Newspapers

Newspapers in Egypt often wrote about world events and criticized both fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. The Second Italo-Ethiopian War (Italy's invasion of Ethiopia) worried Egyptians. Italy's aggressive actions were called imperialism. The newspaper al-Muqattam called it "white imperialism," while al-Ahram "called on the civilized world to join together to oppose Fascist imperialism." An al-Ahram article in April 1937 said that Mussolini's attempts to reach out to the Arab world were just fake. Nazi Germany's expansion into Austria and Czechoslovakia also worried the press. Al-Muqattam also criticized the racial laws in Nazi Germany, saying:

"Who are these Aryans who boast of Aryan origin? After all, the Arab and Persian peoples— Egyptians, Iraqis, Syrians, Palestinians, Iranians— who are assumed not be Aryan are the ones who brought civilization as we know it to the world. These peoples lighted the human path to life, and from them the three monotheistic religions emerged, religions that the so-called Aryans accept and believe. So what is the advantage of these Aryan nations over them?"

Political cartoons showed Mussolini and Hitler as both dangerous and silly.

Italy Invades Egypt

The Italian invasion of Egypt (September 13–18, 1940) was a small attack towards Mersa Matruh. It wasn't meant to achieve big goals because Italy didn't have enough trucks, fuel, or radios. Musaid was heavily bombed and then taken. The British pulled back past Buq Buq on September 14 but kept bothering the Italian advance. The British continued to retreat, going to Alam Hamid on the 15th and Alam el Dab on the 16th. An Italian force of fifty tanks tried to go around the British, which made the British rearguard (the troops protecting the back) retreat east of Sidi Barrani. The Italian general, Graziani, stopped the advance there.

Even though Mussolini pushed them, the Italians dug in around Sidi Barrani and Sofafi, about 80 miles (130 km) west of the British defenses at Mersa Matruh. The British expected the Italian advance to stop there and started watching their positions. British navy and air attacks continued to bother the Italian army. The 7th Armoured Division prepared to face an attack on Matruh.

Italy's Defeat

The British forces attacked the Italian camps. On December 10, the 4th Armoured Brigade cut the main road between Sidi Barrani and Buq Buq. The 7th Armoured Brigade stayed ready, and another British group blocked an approach from the south.

The 16th Brigade, with Matilda II tanks, RAF planes, Royal Navy ships, and artillery, started its attack at 9:00 a.m. The fighting went on for hours without much progress. Then, at 1:30 p.m., the Italian "Blackshirts" holding two strongholds suddenly gave up. The British kept moving forward with more tanks and infantry.

The second attack began just after 4:00 p.m. Italian artillery fired at the British soldiers as they got out of their vehicles. The last ten Matildas drove into the western side of the Sidi Barrani defenses. Even though Italian artillery fired at them, it didn't work well. At 6 p.m., about 2,000 Blackshirts surrendered. In two hours, the first goals were captured. Only a small area east of the harbor, held by Blackshirts and parts of the 1st Libyan Division, was still fighting. The British continued advancing until they reached Mersa Brega by February 1941.

Germany Steps In

Adolf Hitler sent his army to North Africa starting in February 1941. Nazi Germany's General Erwin Rommel and his Deutsches Afrikakorps had just won battles at Tobruk in Libya. In a fast, powerful attack called a blitzkrieg, they easily defeated the British forces. Within weeks, the British were pushed back into Egypt.

Germany's Defeat

Rommel's attack was finally stopped at a small railway stop called El Alamein, which was 150 miles (240 km) from Cairo. In July 1942, Rommel lost the First Battle of El Alamein. This was largely because it was hard for him to get supplies over such long distances, a problem both sides faced in the desert war. The British were now very close to their supplies and had fresh troops. In early September 1942, Rommel tried again to break through the British lines during the Battle of Alam el Halfa. But he was stopped for good by the new British commander, Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery.

With British forces from Malta stopping his supplies at sea, and the huge distances his troops had to travel in the desert, Rommel couldn't hold the El Alamein position forever. Still, it took a large, planned battle from late October to early November 1942, called the Second Battle of El Alamein, to defeat the Germans. This forced them to retreat west towards Libya and Tunisia.

Egyptian Soldiers Join In

Even though Egypt was a British military zone and British forces were there, many Egyptian Army units also fought alongside them. Some units included the 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th Infantry Regiments, the 16th and 12th Cavalry Regiments, the 17th Horse Artillery Regiment, and the 22nd King's Own Artillery Regiment. Other units also fought, but their names are not known. Besides these units, the Anti-Aircraft Artillery Regiments all over Egypt played a very important role in shooting down German air attacks on Alexandria, Cairo, Suez, and the Northern Delta.

Allied Victory

The leadership of the United Kingdom's General Bernard Montgomery at the Second Battle of El Alamein, also called the Battle of Alamein, was a major turning point in World War II. It was the first big victory by British Commonwealth forces over the German Army. The battle lasted from October 23 to November 3, 1942. After the First Battle of El Alamein had stopped the Axis advance, British general Bernard Montgomery took command of the Eighth Army in August 1942. Success in this battle changed the course of the North African Campaign. Some historians believe that this battle, along with the Battle of Stalingrad, were the two most important Allied victories that led to the eventual defeat of Nazi Germany.

By July 1942, the German Afrika Korps, led by General Rommel, had pushed deep into Egypt. They were threatening the very important Allied supply route through the Suez Canal. Rommel's supply lines were stretched too far, and he wasn't getting enough new soldiers. But he knew that the Allies were getting many more troops. So, Rommel decided to attack the Allies while they were still building up their forces. This attack on August 30, 1942, at Alam Halfa, failed. Expecting a counterattack from Montgomery's Eighth Army, the Afrika Korps dug in. After six more weeks of gathering forces, the Eighth Army was ready to attack. 200,000 men and 1,000 tanks under Montgomery moved against the 100,000 men and 500 tanks of the Afrika Korps.

The Allied Plan

With Operation Lightfoot, Montgomery wanted to cut two paths through the Axis minefields in the north. Then, tanks would go through and defeat the German tanks. Attacks in the south would distract the rest of the Axis forces and keep them from moving north. Montgomery expected a twelve-day battle in three parts: "breaking in, the dog-fight, and finally breaking the enemy."

The Commonwealth forces used many tricks in the months before the battle to fool the Axis command. They wanted to hide where and when the battle would happen. This plan was called Operation Bertram. They built a fake pipeline, bit by bit. This made the Axis believe the attack would happen much later and much further south. To make the trick even better, they built fake tanks out of plywood frames over jeeps and put them in the south. In a reverse trick, the real tanks for the battle in the north were disguised as supply trucks by putting removable plywood covers over them.

The Axis forces had dug in along two lines, which the Allies called the Oxalic Line and the Pierson Line. They had laid about half a million mines, mostly anti-tank mines, in an area they called the Devil's gardens.

The Battle

The battle began at 9:40 p.m. on October 23 with a long artillery bombardment. The first goal was the Oxalic Line, and the tanks planned to go over this and then to the Pierson Line. However, the minefields were not fully cleared when the attack started.

On the first night, the attack to create the northern path fell three miles short of the Pierson line. Further south, they had made better progress but were stopped at Miteirya Ridge.

On October 24, the Axis commander, General Stumme (Rommel was on sick leave in Austria), died of a heart attack while under fire. After some confusion because Stumme's body was missing, General Ritter von Thoma took command of the Axis forces. Hitler first told Rommel to stay home and recover, but then he got worried about the worsening situation and asked Rommel to return to Africa if he felt able. Rommel left right away and arrived on October 25.

For the Allies in the south, after another failed attack on the Miteirya Ridge, the attack was stopped. Montgomery then focused the attack on the north. There was a successful night attack on October 25-26. Rommel's immediate counter-attack failed. The Allies had lost 6,200 men compared to the Axis's 2,500. But while Rommel only had 370 tanks ready for action, Montgomery still had over 900.

Montgomery felt that the attack was losing its power and decided to regroup. There were a number of small fights, but by October 29, the Axis line was still holding. Montgomery was still confident and prepared his forces for Operation Supercharge. The endless small operations and constant attacks by the Allied air force had by then reduced Rommel's effective tank strength to only 102.

The second major Allied attack of the battle was along the coast. The goal was to capture the Rahman Track and then take the high ground at Tel el Aqqaqir. The attack began on November 2, 1942. By the 3rd, Rommel had only 35 tanks ready for action. Even though he was holding back the Allied advance, the pressure on his forces made a retreat necessary. However, on the same day, Rommel received a "victory or death" message from Hitler, stopping the withdrawal. But the Allied pressure was too great, and the German forces had to retreat on the night of November 3–4. By November 6, the Axis forces were fully retreating, and over 30,000 soldiers had surrendered.

What Happened Next

Churchill's Summary

Winston Churchill famously summed up the battle on November 10, 1942, with these words: "now this is not the end, it is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning."

The battle was Montgomery's greatest success. He later took the title "Viscount Montgomery of Alamein" when he was given a special honor.

The Torch landings in Morocco later that month marked the real end of the Axis threat in North Africa.

Egyptian Ships Sunk

In total, 14 Egyptian ships were sunk during the war by German submarines (U-boats). These included: one ship sunk by German submarine U-83, three ships sunk and one damaged by German submarine U-77, and nine ships sunk by German submarine U-81.

| Date | Ship | sunk/damaged by | Tonnage | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 April 1942 | Bab el Farag | U-81 | 105 | Sunk |

| 16 April 1942 | Fatouhel el Rahman | 97 | Sunk | |

| 19 April 1942 | Hefz el Rahman | 90 | Sunk | |

| 22 April 1942 | Aziza | 100 | Sunk | |

| 11 February 1943 | Al Kasbanah | 110 | Sunk | |

| 11 February 1943 | Sabah al Kheir | 36 | Sunk | |

| 20 March 1943 | Bourgheih | 244 | Sunk | |

| 28 March 1943 | Rouisdi | 133 | Sunk | |

| 25 June 1943 | Nisr | 80 | Sunk | |

| 8 June 1942 | Said | U-83 | 231 | Sunk |

| 30 July 1942 | Fany | U-77 | 43 | Sunk |

| 1 August 1942 | St. Simon | 100 | Sunk | |

| 6 August 1942 | Adnan | 155 | Damaged | |

| 6 August 1942 | Ezzet | 158 | Sunk |

See also

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |