Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Earl of Cromer

|

|

|---|---|

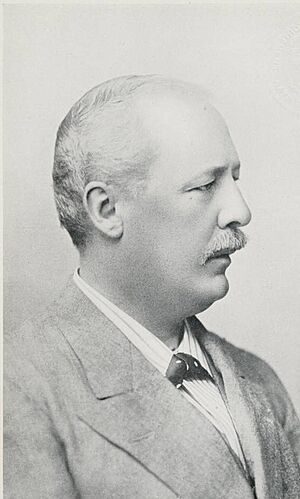

The Earl of Cromer in 1895

|

|

| Consul-General of Egypt | |

| In office 11 September 1883 – 6 May 1907 |

|

| Nominated by | William Ewart Gladstone |

| Appointed by | Victoria |

| Monarch | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by | Eldon Gorst |

| Controller-General in Egypt | |

| In office 1878–1879 |

|

| Nominated by | Benjamin Disraeli, the Earl of Beaconsfield |

| Appointed by | Queen Victoria |

| Monarch | Isma'il Pasha |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Edward Baldwin Malet |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Evelyn Baring

26 February 1841 Cromer, Norfolk, England |

| Died | 29 January 1917 (aged 75) Westminster, London, England |

| Nationality | |

| Spouses |

|

| Children |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation | Military officer, politician |

| Awards |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Army |

| Years of service | 1860–1877 |

| Rank | Major |

| Unit | Royal Artillery |

Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer (born February 26, 1841 – died January 29, 1917) was an important British leader, diplomat, and colonial administrator. He is best known for his long service in Egypt. He first worked as the British controller-general in Egypt from 1879. Later, he became the British agent and consul-general in Egypt from 1883 to 1907. During this time, Britain had taken control of Egypt, and Baring was effectively in charge of the country's money and government.

Baring's plans helped Egypt's economy grow in some ways. However, they also made Egypt rely more on growing certain crops for money. Some social programs, like the public school system, also became less developed during his time.

Contents

Early Life and Military Career

Evelyn Baring was born in England in 1841. He was the ninth son of Henry Baring. His family was well-known, as his great-grandfather, John Baring, had started the famous Barings Bank. When Evelyn was seven, his father died, and he was sent to boarding school.

At 14, he joined the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. He became a lieutenant in the Royal Artillery at 17. His first job was on the island of Corfu. While there, he felt he needed more education, so he taught himself Greek and became fluent in Italian.

In 1862, Baring became an assistant to Sir Henry Storks, a British official. He traveled with Storks to Malta and Jamaica. In Jamaica, Storks led an investigation into a rebellion. After this, Baring attended the Army's Staff College. He then worked for two years at the War Office, helping to improve the army. In 1871, he was promoted to second captain.

Baring decided he didn't want to stay in the military. In 1872, he went to India to work for his cousin, Lord Northbrook, who was the Viceroy of India. Baring quickly found he was good at managing things. When Northbrook left in 1876, Baring returned to England. He married Ethel Errington and was promoted to major in 1878. The next year, he left the army.

British Controller-General of Egypt

When Baring first arrived in Egypt in 1877, the country was in serious financial trouble. The ruler of Egypt, Ismail Pasha, had borrowed a lot of money from European banks. He used this money for projects like the Suez Canal, for himself, and to cover money shortages. Egypt's economy relied heavily on cotton, which had been very profitable during the American Civil War. But after the war, American cotton returned to the market, and cotton prices dropped sharply. Ismail Pasha could no longer pay back his loans.

Ismail Pasha tried to get more tax money from his parliament, but they refused. In desperation, he asked European countries for help. This led to a system called the "Dual Control." Under this system, a French and a British official were put in charge of Egypt's finances. Sir Evelyn Baring became the British Controller. This move by Ismail Pasha opened the door for foreign control over Egypt's money.

Baring and the French controller had a lot of power over Egypt's money. When Ismail Pasha refused to declare that he was bankrupt, Baring pushed the British government to remove him from power, which happened in 1879. Most Egyptians blamed Ismail for the country's money problems, so they were relieved when he was removed. Ismail's son, Tawfiq, took over and worked with the European officials.

Consul-General of Egypt

A rebellion led by an Egyptian colonel named Ahmed 'Urabi threatened the Egyptian government. After Britain stepped in with military force in 1882, Baring returned to Egypt. He became the British agent and consul-general. His job was to make small changes and then have British troops leave. However, Baring believed that Britain should stay in Egypt for a long time. He did not support Egyptian demands for independence.

Baring's first action as Consul-General was to approve a plan that created a parliament with no real power. This plan said that Britain needed to oversee any changes in Egypt. It also made sure that Britain's interests in the Suez Canal area were protected. Baring thought that Egyptians were not good at managing their own country, so a long British presence was needed for any improvements.

He created a new rule called the Granville Doctrine. This rule allowed Baring and other British officials to choose Egyptian politicians who would cooperate with Britain. It also gave them the power to fire Egyptian ministers who didn't follow British orders. Under Baring, British officials were placed in important government jobs. A new system, called the "Veiled Protectorate," was started. This meant that the Egyptian government looked like it was in charge, but British officials held the real power. Baring was the true ruler of Egypt until 1907. This system worked well for the first ten years because Tawfiq Pasha was a weak leader who was happy to let others handle government duties.

The Egyptian army was seen as untrustworthy by Baring. So, it was disbanded, and a new army was created, organized like the British army. By 1887, Egypt's finances were stable. Baring also made the Egyptian government give up on trying to take back Sudan, which they had lost control of. Baring managed the budget carefully and promoted projects to improve irrigation (watering crops). This brought a lot of economic success to Egypt.

Baring believed that one day, British control of Egypt would end, and Egypt would become fully independent. But he thought this would only happen once Egyptians learned how to govern themselves properly. Some historians say that Baring believed that "subject races" (people under colonial rule) could not govern themselves. They argue that he thought these people didn't really need or want self-government. Instead, he believed they needed to be kept happy and well-fed, which would allow the rich to make money and work with the British rulers.

In 1892, Tawfiq died, and Abbas Hilmi II became the new ruler. Abbas was young and wanted to remove foreign influence. He encouraged a movement for Egyptian independence. But Baring quickly forced him to cooperate.

Lord Cromer had seen in India that advanced education could lead to people wanting independence. Because of this, in Egypt, he reduced the money for education. He closed many special colleges and focused the school lessons on job skills. He also made tuition fees higher, which meant fewer Egyptians could afford to go to school.

Baring faced criticism after the 1906 Denshawai Incident, where Egyptian farmers were severely punished. Even though he was not in Egypt at the time, the new British government decided to be more lenient towards Egypt. Baring felt his time was ending and resigned in April 1907, saying it was for health reasons. In July 1907, the British Parliament gave him £50,000 to recognize his "excellent services" in Egypt.

Honors and Awards

In August 1901, Baring was given the titles Viscount Errington and Earl of Cromer. In June 1902, he received an honorary degree from the University of Oxford. In 1906, King Edward VII made Baring a Member of the Order of Merit, a special honor.

Baring's Views on Society

Baring held strong beliefs about Western and Eastern cultures. He thought that Westerners were better than Egyptians in every way. He believed that the "Orient" (the East) and its people needed to be controlled by the Western world.

In 1901, Baring noticed that more students were enrolling in primary schools, which led to a higher demand for secondary education. Both boys and girls wanted more education to get government jobs and improve their lives. Instead of increasing education opportunities, Baring believed that the government should not pay for education. He raised tuition fees at primary schools to reduce the number of students. Both boys' and girls' schools were affected by these changes. Baring worried that an educated working class might start movements against the British government.

Baring also tried to limit job opportunities for women. He suggested that female doctors were not as skilled as male doctors and that in Western countries, men were the most trusted medical professionals. When Egyptians complained about not having enough jobs, Baring even denied that there was such a thing as an "Egyptian nationality."

Baring believed that Egyptian society and the Islamic world were not as good as the Western world. He thought that Egypt could only succeed if it removed Islam from its culture. He specifically argued that Western Christianity improved the status of women, while Islam, in his view, lowered women's status through practices like wearing the veil and separating genders.

Baring's ideas about segregation and the veil influenced public discussions about women and Islam. He started campaigns in Egypt to encourage women to stop wearing the veil. For example, Qasim Amin, a lawyer educated in France, was influenced by Baring's ideas. Amin became known as one of the first feminists because he spoke out against the veil, saying it was oppressive. His work, shaped by Baring's thoughts, helped bring the topic of women's "subjugation" in Islam into discussions about colonial rule and Westernization.

Later Years

Baring returned to Britain when he was 66 years old and spent a year getting his health back. In 1908, he published a two-volume book called Modern Egypt, which told the story of events in Egypt and Sudan since 1876. In 1910, he wrote Ancient and Modern Imperialism, a book comparing the British and Roman Empires. In 1914, after World War I began, the Egyptian ruler Abbas II of Egypt supported the Ottoman Empire. The British removed Abbas from power. This allowed Baring to publish his thoughts on Abbas II in a book in 1915.

Baring loved classic literature and could speak Greek, Latin, Italian, French, and Turkish. However, he never learned Arabic, which was the language of most Egyptians. In the early 1900s, a movement for Egyptian independence started to grow. But Baring, who became more distant as he got older, thought it was unimportant.

Baring was also active in British politics. As Lord Cromer, he was a member of the House of Lords. He joined the free-trade group within the Conservative and Unionist Party. Baring was a leader against women getting the right to vote. He was president of the Men's League for Opposing Woman Suffrage in 1908, and later the National League for Opposing Woman Suffrage from 1910 to 1912.

In 1916, at 75 years old, Cromer was asked to lead the Dardanelles Commission, which investigated a military campaign. This job was too much for his health. He died on January 29, 1917, and is buried in Bournemouth, England.

Family

Evelyn Baring's brother was Edward Baring, 1st Baron Revelstoke. Cromer had three sons: Rowland Baring, 2nd Earl of Cromer (1877–1953), who took over his title; Hon. Windham Baring (1880–1922), who became a director at Baring Brothers bank; and Evelyn Baring, 1st Baron Howick of Glendale (1903−1973), who was a High Commissioner for Southern Africa and a Governor of Kenya.

Selected Works

Books written by Lord Cromer include:

- Modern Egypt. New York: The Macmillan Company. 2001 ed. (reprint) vol 1. ASIN B000NPPRR8. ISBN: 1-4021-8339-9 and vol 2. ISBN: 1-4021-7830-1

- Modern Egypt, vol. I. New York: MacMillan, 1908

- Modern Egypt, vol. II. New York: MacMillan, 1908

- Ancient and Modern Imperialism, New York: Longmans, 1910

- Disraeli, London: MacMillan, 1912

- Political and Literary Essays, London: MacMillan, 1913