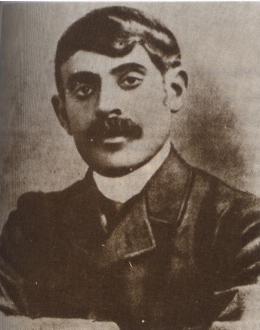

Qasim Amin facts for kids

Qasim Amin (born December 1, 1863, in Alexandria – died April 22, 1908, in Cairo) was an important Egyptian thinker and judge. He was one of the people who helped start the Egyptian national movement and Cairo University. Qasim Amin is often seen as one of the first people in the Arab world to speak up for women's rights. He believed that improving the lives of women would make Egypt stronger.

Amin was a key figure in the Nahda Movement, which was a time of great change and new ideas in the Arab world. He spoke out against practices like women wearing the veil, being kept separate from men, marrying very young, and not getting enough education. Some experts today discuss whether his ideas truly helped women or if they were influenced by Western views at the time. He thought that if Egypt didn't become more modern like European countries, it wouldn't be able to succeed.

He was inspired by thinkers like Charles Darwin and John Stuart Mill, who believed in equality. Amin also had friends like Muhammad Abduh and Saad Zaghloul who influenced his ideas. He believed that the Quran actually supported women's rights and that traditional Muslim customs were holding women back. Born into a wealthy family, Amin studied law and even received a scholarship to study in France. This experience in France, especially seeing how women lived there, greatly influenced his desire to help Egyptian women.

His journey to help women began when he wrote a response in 1894 to a French Duke who had criticized Egyptian culture and its women. Later, in 1899, he wrote a famous book called Tahrir al mara'a (The Liberation of Women). In this book, he argued that the veiling of women, their lack of education, and their limited freedom were making Egypt weak. He believed that Egyptian women were essential for a strong nation, and their roles needed to change for Egypt to improve. Qasim Amin is known for connecting education with national strength, which led to the founding of Cairo University and the National Movement in the early 1900s.

Contents

Early life

Qasim Amin was born into a wealthy and powerful family in Egypt. His father, Muhammad Amin Bey, was a governor before the family moved to Alexandria, where Qasim was born. His father later became a commander in the army. Qasim's mother also came from an important Egyptian family.

Education

As a young boy, Amin went to many of Egypt's best schools. He started primary school in Alexandria. In 1875, he went to Cairo's Preparatory School, which had a strict, European-style learning program. By 1881, when he was 17, he earned his law degree. He was one of only 37 students to receive a special scholarship to study at the University of Montpellier in France. He studied there for four years.

- University of Montpellier 1881-1885

- Khedivial Law School

- Cairo preparatory school

- Alexandria palace school

Marriage

In 1894, Amin married Zeyneb, whose father was Admiral Amin Tafiq. This marriage connected him to another important Egyptian family. His wife had been raised by a British nanny, and Amin decided his own daughters should also have a British nanny. Amin believed that women should not wear the niqab (a face veil). While he couldn't convince his wife to stop wearing it, he hoped to teach the younger generation, like his daughters, not to wear it.

Career

After finishing his studies in France, Amin became a civil servant for the British Empire in Egypt. In 1885, he became a judge in the Mixed Courts. These courts, started in 1875, combined French and Islamic legal systems. Judges came from different European countries. Amin worked successfully with these international legal officers. The Mixed Courts helped manage Egypt's business life during a time when foreign governments had a lot of control. By 1887, he joined an Egyptian government office that was mostly run by Westerners. Within four years, he was chosen as one of the Egyptian judges for the National courts.

Cairo University

Qasim Amin was one of the people who helped create the first Egyptian University, which was then called the National University. This university later became Cairo University. He was part of the committee that set it up. Qasim Amin strongly believed that Egypt needed a university like those in Western countries.

Posts

- Chancellor of the Cairo National Court of Appeals

- Secretary general of Cairo University

- Vice President of Cairo University

Qasim was chosen as the first secretary general of Cairo University.

Charis Waddy, an expert on Islamic studies, described Qasim as 'a brilliant young lawyer'.

The Nahda (Awakening) influence

Qasim Amin was a central figure in the Nahda Movement, which was a period of "awakening" or "rebirth" in the Arab world during the late 1800s and early 1900s. He was greatly influenced by leaders of this movement, especially Muhammad Abduh, whom he worked with as a translator in France. Abduh believed that traditional Islamic practices had caused the Islamic world to decline, making it easier for Western powers to colonize countries like Egypt. At that time, Egypt was partly controlled by the British Empire and France.

Abduh thought that some traditional Muslims had moved away from the true teachings of Islam, which he believed supported greater intellect, power, and fairness. He also criticized how men dominated women within families, claiming it was done in the name of Islamic law. Abduh encouraged all Muslims to unite, return to the true message of Allah (which he believed gave women equal status), and resist Western control.

Amin was deeply affected by Abduh's ideas. He also believed that traditional customs, not true Islamic laws, were keeping Egyptian women from their rights. He felt this made Egyptian society weaker compared to the Western world. Amin spent much of his life arguing that changing women's roles in Egyptian society, by making them freer and more educated, would improve the entire nation.

Attitude on Veiling

In his 1899 book The Liberation of Women, Qasim Amin argued that the veil should be removed. He believed that changing customs about women, especially getting rid of the veil, was important for Egypt to become a modern society. Amin thought that the veil and keeping women separate created "a huge barrier between woman and her elevation, and consequently a barrier between the nation and its advance."

However, some Muslim scholars, like Leila Ahmed, have criticized Amin's reasons for wanting to remove the veil. They suggest he might have been influenced by colonial ideas rather than truly understanding women's needs. Amin argued that if girls were educated but then had to wear the veil and stay secluded, they would forget what they learned. He felt that the age when girls started veiling (12-14) was crucial for their development, and veiling stopped this. He thought girls needed to mix freely with men to learn. This idea seems to go against his earlier view that women only needed primary school education.

When people worried that removing the veil would harm women's purity, Amin responded by pointing to Western civilization. He asked if Egyptians thought Europeans, who had achieved so much in science and knowledge, wouldn't know how to protect women's purity. He suggested that if the veil had been good, Europeans wouldn't have stopped using it.

Words on Marriage and Divorce

Qasim Amin believed that marriages among Muslims were not based on love. He thought that women were often seen as the cause of problems in Muslim marriages, focusing on physical traits rather than a husband's intelligence or feelings. To Qasim Amin, a woman's main duties in marriage were housework and raising children. Because of this, he felt that a primary-school education was enough for women.

Even though he saw women as less important than men, Qasim Amin did support making divorce a legal process. Traditionally, a divorce could happen just by a man saying "I have divorced you" three times. Amin thought this was not serious enough. He believed that the lack of a proper legal system for divorce led to many divorces in Cairo. He suggested that formal legal statements should be required for divorce. This would make sure husbands were truly serious about separating from their wives. Amin criticized Muslim scholars for focusing too much on the exact words of divorce rather than on creating a fair legal process. He thought a legal system would stop men from accidentally divorcing their wives during jokes or arguments.

Works

Amin was greatly influenced by the ideas of Darwin, Herbert Spencer, and John Stuart Mill. He was also friends with Muhammad Abduh and Saad Zaghloul.

He was an early supporter of women's rights in Egyptian society. His 1899 book The Liberation of Women (Tahrir al mara'a) and its 1900 follow-up The New Woman (al mara'a al jadida) explored why Egypt had fallen under European control. He concluded that the main reason was the low social and educational status of Egyptian women.

Amin highlighted the difficult situation of wealthy Egyptian women who could be kept like "prisoners in her own house and worse off than a slave." He made this criticism based on his understanding of Islamic teachings. He said that women should develop their minds so they could raise the nation's children well. This could only happen if they were freed from seclusion (purdah), which was forced upon them by "the man's decision to imprison his wife," and given the chance to get an education.

Some modern feminist scholars, like Leila Ahmed, have questioned whether he truly deserves the title "father of Egyptian feminism." Ahmed points out that in the society of that time, where men and women were often kept separate, Amin likely had very little contact with Egyptian women outside his immediate family and servants. Therefore, his description of Egyptian women as backward and ignorant might have been based on limited information. Ahmed also suggests that by strongly criticizing Egyptian women and praising European society, Amin might have promoted Western ideas of male dominance instead of true feminism.

Books by Qasim Amin

- 1894 - Les Egyptiens. Response a M. le duc D'Hartcourt: This book was written to respond to Duke Hartcourt's strong criticism of Egyptian life and women. Amin defended Islam's treatment of women in this book.

- 1899 - Tahrir al- mar'a (The Liberation of Women): Amin was not satisfied with his first response. In this book, he called for women to be educated, but only up to primary school. He still believed men should lead women but suggested changing laws about divorce, polygamy, and removing the veil. He wrote this book with Muhammad Abduh and Ahmad Lufti al-Sayid, using many verses from the Quran to support his ideas.

- 1900 - al-Mar'a al-jadida (The New Woman): In this book, Amin imagined a "new woman" in Egypt who would act and behave like Western women. This book was seen as more liberal. He used ideas from social Darwinism in his arguments. He wrote, "A woman may be given in marriage to a man she does not know who forbids her the right to leave him and forces her to this or that and then throws her out as he wishes: this is slavery indeed."

Other works

- "Huquq al-nisa fi'l-islam" ("Women's rights in Islam")

- "Kalimat" ("Words")

- "Ashbab wa nata if wa-akhlaq wa-mawa. Iz" ("Causes, effects, morals, and recommendations")

- "Al-a'mal al-kamila li-Qasim Amin: Dirasa wa-tahqiq" ("The Full Works of Qasim Amin: Study and Investigation")

- "Al-Misriyyun" ("Egyptians")

- "The Slavery of Women"

- "They young Woman, 1892"

- "Paradise"

- "Mirror of the Beautiful"

- "Liberation of Women"

Intellectual contribution

Qasim Amin was a strong supporter of social reform in Egypt during the late 1800s, when it was under British control. He wanted Egyptian families to be more like those in France, where he felt women were not controlled by the same male-dominated culture as in Egypt. Amin believed that Egyptian women were not allowed their rights under the Quran to manage their own affairs, marry, and divorce freely.

He spoke out against polygamy (a man having more than one wife), saying it showed "intense contempt of women." He believed marriage should be a mutual agreement. He also opposed the Egyptian custom of "veiling" women, calling it a major sign of women's oppression. Amin argued that the niqab made it hard to identify women and made them more noticeable and distrusted by men when they walked in public.

He also said that men in the West treated women with more respect, allowing them to go to school, walk without a veil, and speak their minds. This freedom, he insisted, "contributed significantly" to the knowledge and strength of the nation. He supported the idea that educated women would raise educated children. He believed that if women were kept at home, without a voice or education, they would waste their time and raise children who would be lazy, ignorant, and untrusting. Once educated, these women could become better mothers and wives by learning to manage their homes better.

Amin used an example to explain his point: "Our present situation resembles that of a very wealthy man who locks up his gold in a chest. This man," he said, "unlocks his chest daily for the mere pleasure of see his chest. If he knew better, he could invest his gold and double his wealth in a short time." Therefore, he believed it was very important for Egypt that women's roles should change. Although he still thought Egypt should be a society led by men, he believed its women should remove the veil and receive a primary education. He saw this as a step towards a stronger Egyptian nation, free from British control.

Quotes

- "I do not advocate the equality between men and women in education for this is not necessary."

- "Our laziness has caused us to be hostile to every unfamiliar idea."

- "The number of children killed by ignorant women every year exceeds the number of people who die in the most brutal wars."

- "A good mother is more useful to her species than a good man, while a corrupt mother is more harmful than a corrupt man."

- "It is impossible to be successful men if they do not have mothers capable of raising them to be successful."

- "There is no doubt that the man's decision to imprison his wife contradicts the freedom which is the woman's natural right."

- "The woman who is forbidden to educate herself save in the duties of the servant, or is limited in her educational pursuits is indeed a slave, because her natural instincts and God-given talents are subordinated in deference to her condition, which is tantamount to moral enslavement."

See also

In Spanish: Qasim Amin para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |