Ahmed Urabi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ahmed ʻUrabi Pasha

|

|

|---|---|

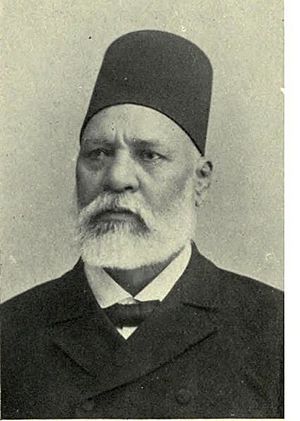

ʻUrabi in 1906

|

|

| Prime Minister of Egypt | |

| In office 1 July 1882 – 13 September 1882 |

|

| Monarch | Tewfik Pasha |

| Preceded by | Raghib Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Mohamed Sherif Pasha |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 31, 1841 Zagazig, Egypt |

| Died | September 21, 1911 (aged 70) Cairo, Egypt |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | Brigadier general |

| Battles/wars | Ethiopian–Egyptian War ʻUrabi revolt Anglo-Egyptian War |

Ahmed ʻUrabi (born March 31, 1841 – died September 21, 1911) was an important Egyptian army officer. He is also known as Ahmed Ourabi or Orabi Pasha.

ʻUrabi was the first major political and military leader in Egypt to come from a peasant background, known as fellahin. In 1879, he took part in a protest that grew into the ʻUrabi revolt. This revolt was against the ruler of Egypt, Khedive Tewfik, whose government was heavily influenced by Britain and France.

ʻUrabi was promoted to Tewfik's government and started making changes to Egypt's army and government. However, protests in Alexandria in 1882 led to a British attack and invasion. This resulted in ʻUrabi and his supporters being captured. Britain then took control of Egypt. ʻUrabi and his allies were sent away to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) as a punishment.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Ahmed ʻUrabi was born in 1841 in a village called Hirriyat Razna. This village is near Zagazig, about 80 kilometers north of Cairo. His father was a village leader and quite wealthy. This allowed ʻUrabi to get a good education.

After finishing elementary school in his village, he went to Al-Azhar University in 1849 to continue his studies. He then joined the army and quickly rose through the ranks. By the age of 20, he had become a lieutenant colonel.

ʻUrabi's journey from a peasant background to a high military rank was unusual. It was made possible by the modern changes brought by Khedive Ismail. Ismail removed old rules that favored people of Balkan, Circassian, and Turkish origin in the army. He wanted a modern Egyptian army and government with people from all backgrounds. Without these changes, ʻUrabi might not have risen so high.

ʻUrabi served in the Ethiopian-Egyptian War (1874-1876). He helped with communications for the Egyptian army. Egypt lost this war. It is said that ʻUrabi was very upset by how badly the war was managed. This experience made him interested in politics and strongly against the Khedive's rule.

Leading Protests Against Tewfik

ʻUrabi was a powerful speaker. Because he came from a peasant family, many people saw him as a true voice for the Egyptian people. His followers even called him 'El Wahid', meaning 'the Only One'.

When Khedive Tewfik made a new rule preventing peasants from becoming officers, ʻUrabi led a group to protest. They were against the special treatment given to aristocratic officers, who were often of foreign descent. ʻUrabi often spoke out against the unfair treatment of Egyptians in the army. He and his supporters, who included most of the army, succeeded. The unfair law was removed. In 1879, they formed the Egyptian Nationalist Party. Their goal was to create a stronger Egyptian national identity.

In February 1882, ʻUrabi and his army allies joined with other reformers. They demanded big changes. This movement, known as the ʻUrabi revolt, aimed for fairness for all Egyptians under the law. With support from peasants, ʻUrabi wanted to free Egypt and Sudan from foreign control. He also wanted to end the Khedive's absolute rule, as the Khedive was under European influence. Egyptian leaders demanded a constitution that would give power to a parliament. The revolt also showed anger about the too much influence of foreigners, including the Turkish-Circassian ruling class from the Ottoman Empire.

Plans for a Parliament

ʻUrabi was first promoted to Bey, a high title. Then he became an under-secretary of war, and finally, a member of the government. Plans were made to create a parliament. During the last months of the revolt (July to September 1882), ʻUrabi was said to be the Prime Minister of a new government based on the will of the people.

Feeling threatened, Khedive Tewfik asked the Ottoman Sultan for help against ʻUrabi. Egypt and Sudan were still technically loyal to the Sultan. However, the Sultan was slow to respond to the Khedive's request.

British Intervention

Britain was worried that ʻUrabi might not pay back Egypt's huge debts. They also feared he might take control of the Suez Canal, a very important waterway. So, Britain and France sent warships to Egypt to prevent this.

Khedive Tewfik fled to the protection of these ships, moving his government to Alexandria. The strong presence of warships made people fear an invasion. This led to anti-Christian riots in Alexandria on June 12, 1882. The French fleet left, but the Royal Navy ships in the harbor began firing on the city's defenses. This happened after Egyptians ignored a warning to remove their artillery.

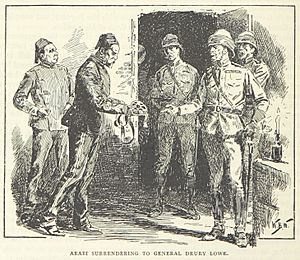

In September, a British army landed in Alexandria. They were stopped at the Battle of Kafr El Dawwar and could not reach Cairo. Another British army, led by Sir Garnet Wolseley, landed in the Canal Zone. On September 13, 1882, they defeated ʻUrabi's army at the Battle of Tell El Kebir. After this, the British forces marched to Cairo. Cairo surrendered without a fight, and ʻUrabi and other nationalist leaders were captured.

Exile and Return

ʻUrabi was put on trial by the restored Khedive's government on December 3, 1882. He was defended by British lawyers. ʻUrabi's defense argued that he had acted according to Egyptian law and had remained loyal to the Egyptian people.

As part of a deal with the British, ʻUrabi pleaded guilty. He was sentenced to death, but this was immediately changed to being sent away for life. He left Egypt on December 28, 1882, for Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). His home in Kandy, Ceylon, is now the Orabi Pasha Cultural Center.

While in Ceylon, ʻUrabi worked to improve education for Muslims there. He supported the founding of Hameed Al Husseinie College in 1884 and Zahira College in 1892.

In May 1901, Khedive Abbas II, Tewfik's son, allowed ʻUrabi to return to Egypt. Abbas II was a nationalist and opposed British influence. ʻUrabi returned on October 1, 1901, and lived in Egypt until his death on September 21, 1911.

Lasting Impact

The British said their intervention in Egypt would be temporary. However, British forces stayed in Egypt for many decades. In 1914, during World War I, Britain removed Khedive Abbas II. They feared he might side with the Ottoman Empire against them. Britain then declared Egypt a British protectorate, meaning they controlled it.

Five years later, in 1919, Egyptian nationalists protested against British control. This led to the Egyptian Revolution of 1919. As a result, Britain officially recognized Egypt as an independent country in 1922.

ʻUrabi's revolt had a huge and lasting impact on Egypt. It was a very important expression of nationalistic feelings. Historians say that the 1881-1882 revolution helped lay the groundwork for modern politics in Egypt.

In July 1952, when Mohamed Naguib spoke to supporters after overthrowing King Farouk, he connected this new revolution to ʻUrabi's revolt. Naguib quoted ʻUrabi's words to Khedive Tewfik, saying that the people of Egypt were "no longer inheritable" by any ruler. The new government even renamed Ismailia Square, Cairo's main public square, to Tahrir Square (Liberation Square), just as ʻUrabi had done. Later, under Gamal Abdel Nasser, ʻUrabi was celebrated as a great Egyptian patriot and national hero. He also inspired political activists in Ceylon.

Tributes to ʻUrabi

Many places honor Ahmed ʻUrabi:

In Egypt

- Alexandria has a square named Orabi Square.

- In Cairo's Al Mohandessin district, a main street and an underground station are named after him.

- Zagazig's main square has a statue of ʻUrabi on a horse. The university's symbol also features his picture.

Abroad

- Arabi, Louisiana, a town near New Orleans in the USA, was named after ʻUrabi. Its residents felt a connection to his fight for independence.

- The Gaza Strip has a coastal road called Ahmed Orabi Street.

- Colombo, Sri Lanka, has an Orabi Pasha Street in its central area.

- Kandy, Sri Lanka, is home to the Orabi Pasha Cultural Centre.

Famous Quotes

- "How can you enslave people when their mothers bore them free?"

- "Allah has created us free, and did not make us into heritage or estate. So by Allah, the only god, we shall be bequeathed or enslaved no more."

See also

In Spanish: Ahmed Orabi para niños

In Spanish: Ahmed Orabi para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |