Battle of Kafr El Dawwar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Kafr El Dawwar |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Anglo-Egyptian War | |||||||

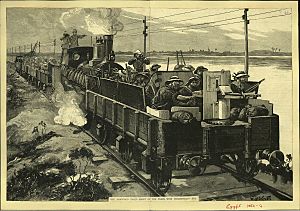

The Armed Train at Alexandria |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,600 men | 2,100 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4 Killed, 27 Wounded |

79 Killed, many wounded, 15 Captured (Estimated 200 total casualties including dead wounded and POWs) |

||||||

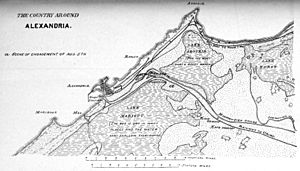

The Battle of Kafr El Dawwar was an important fight during the Anglo-Egyptian War in 1882. It happened near Kafr El Dawwar, Egypt. This battle was fought between the Egyptian army, led by Ahmed ‘Urabi, and British forces, led by Sir Archibald Alison. The Egyptians won this battle. Because of this, the British gave up on trying to reach Cairo from the north. Instead, they moved their main base to Ismailia to try a different route.

Contents

Getting Ready for Battle

After the British attacked and bombed Alexandria on July 11, they took over the city. The Egyptian army then moved back to Kafr El Dawwar. There, they started building a strong camp with trenches to block the way to Cairo.

‘Urabi, the Egyptian leader, asked for one-sixth of all men from every area to join the army at Kafr El Dawwar. All old soldiers were called back to serve again. Horses and food were also collected for the army.

On July 17, Sir Archibald Alison arrived in Alexandria with the first British soldiers. These included the South Staffordshire Regiment and a group from the King's Royal Rifle Corps. With some Royal Marine Light Infantry and many sailors, Alison's force had 3,755 men. They also had nine cannons, six Gatling guns, and four rocket launchers. Alison sent out small groups to find out where the Egyptians were and how strong they were. But he kept his main force inside Alexandria.

More British soldiers arrived on July 24. These were the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry and part of the Royal Sussex Regiment. This added 1,108 men and more cannons. Alison then moved forward to take over Ramleh, where he set up a strong base.

The Egyptian forces in the area were thought to be much larger. They had about 12,000 to 15,000 men. This included four groups of foot soldiers, one group of cavalry (soldiers on horseback), and many cannons. They outnumbered the British in Alexandria by at least four to one.

The Battle Begins

Sir Alison wanted to know how strong the Egyptian defenses at Kafr El Dawwar were. He also heard rumors that the Egyptians might be leaving. So, on the evening of August 5, 1882, he ordered a small attack to test their strength. The plan was to follow the Cairo railway line and the Mahmoudiyah Canal. These two paths ran almost side-by-side towards ‘Urabi's trenches.

The British force was split into two main groups. The left group followed the canal. It had 800 men from the South Staffordshire and Duke of Cornwall's regiments. They also had a naval cannon and 80 mounted infantry (soldiers on horseback) on the east side of the canal. On the west side were 500 riflemen and another cannon.

The right group followed the railway line. This group had 1,000 marines. An armoured train helped them. This special train was designed by Captain Jacky Fisher. It had a large 40-pounder cannon, a Nordenfelt gun, two Gatling guns, and two more cannons. In total, the British force, including 200 sailors working the train and cannons, was about 2,600 men.

The Egyptian soldiers in the front lines were a battalion of the Second Infantry, about 1,200 strong. They also had 900 men from the Mustaphezin Regiment. They could get more help and cannons from the main Egyptian position behind them.

The British soldiers on the east side of the canal moved forward. The mounted infantry led the way. Three officers and six men rode ahead to look around. They suddenly met a large group of Egyptians who started shooting. One officer, Lieutenant Vyse, was badly hurt and died quickly. Private Frederick Corbett bravely tried to help the officer while under heavy fire. He was later given the Victoria Cross, a very high award for bravery.

On the west side of the canal, the British riflemen faced many Egyptian troops hidden in a ditch and thick bushes. The riflemen moved forward carefully, using "fire and movement" tactics. This means some soldiers shoot while others move, then they switch. A cannon moved with them, firing shells into the Egyptian position. The Egyptians shot back, but most of their bullets went over the British soldiers' heads. When the riflemen got close, many Egyptians started to sneak away. When the British were told to attach their bayonets (knives on rifles) and charge, the remaining Egyptians ran away, often throwing down their weapons.

At this point, the British left group was told to stop. Their commander, Colonel Thackwell, thought he had reached his goal. But he had stopped at the wrong white house, a mile too early. This mistake would cause problems for the other British group.

The right group moved by train, with the armoured train in front and the marines in a second train behind. The railway line was broken just past Mahalla Junction. So, the marines got off the train and moved forward, using the railway bank for cover. The Egyptians had already aimed their cannons at the broken part of the track. They started firing at the armoured train. The British cannons on the train fired back until the Egyptian cannons stopped. Then, the smaller cannons moved with the marines, while the large 40-pounder kept firing from the train to help.

As the marines moved ahead of the stopped left group, Egyptian soldiers along the canal banks started shooting at them. Seeing they had no support, the marines charged across the open ground. They fired their rifles and then attacked with fixed bayonets. The Egyptians ran in all directions. Many were shot, and some drowned in the canal trying to escape.

The British were now spread out in a diagonal line across both the canal and the railway. A strong Egyptian force on the east side of the canal fought fiercely with the marines. General Alison, who was with the right group, used this time to look closely at the Egyptian defenses. He did this for about 45 minutes. Around 6:30 PM, as it was getting dark and more Egyptian soldiers were arriving, the British were ordered to pull back. They did this calmly and carefully. By 8 PM, all British soldiers were out of the fighting area.

The British lost one officer and three men killed, and 27 wounded. Most of the wounded were from the right group. An Egyptian deserter (someone who left their army) said that the Egyptians lost three officers and 76 men killed, and many wounded. One Egyptian officer and 14 men were captured. It is thought that the total Egyptian losses were about 200 men.

What People Thought

‘Urabi reported this action as a big victory for Egypt. News spread in Cairo that the British attack had been stopped. In London, The Times newspaper said that the result was "satisfactory" for the British.

However, an American military observer, Caspar Goodrich, had a different view. He said that the attack did not really help the British much. He felt that "valuable lives were sacrificed," meaning soldiers died, and the Egyptians quickly took back the ground they had lost.

Later, some historians called this battle a "British attempt to break through at Kafr Ed-Dawar [which] ended in failure." But most others, like Goodrich, saw it as just a "reconnaissance in force." This means it was a small attack meant only to gather information, not a serious attempt to capture the Egyptian lines.

What Happened Next

More British troops kept arriving in Alexandria in the following days. The main British commander, Sir Garnet Wolseley, arrived on August 15. Two days later, Wolseley ordered many of his troops to get back on their ships. He let it be known that he planned to land his forces in Aboukir Bay. From there, they could attack the Egyptian defenses from the side. On August 19, the British fleet sailed, and 18 ships stopped in the bay as if preparing for an attack. But at 8 PM, a signal was given, and the fleet sailed east towards Port Said.

This whole plan was a trick, or "ruse." Wolseley wanted to make ‘Urabi's forces think the main attack would be near Alexandria. This would distract him from Wolseley's real plan: to land his forces near the Suez Canal. The trick worked very well. The British were able to set up their base at Ismaïlia without any problems. It's not clear if Wolseley ever truly planned to attack Cairo directly from Alexandria. Some accounts suggest he always expected the main battle to be at Tel El Kebir.

Wolseley left a division (a large group of soldiers) at Ramleh to protect Alexandria. This force was led by Sir Edward Hamley. It had two smaller groups called brigades. One brigade, led by Sir Archibald Alison, had soldiers from the Royal Highlanders, Highland Light Infantry, Gordon Highlanders, and Cameron Highlanders. The second brigade, led by Sir Evelyn Wood, had soldiers from the Sussex Regiment, Berkshire Regiment, South Staffordshire Regiment, and King's Shropshire Light Infantry. On August 29, Hamley, Alison, and his brigade were ordered to join the main British force. This left Wood's brigade to guard Ramleh alone.

Fighting around Kafr al-Dawar happened several more times in August 1882. The Egyptians continued to threaten Alexandria. The British made occasional small attacks to check on their positions. But the fighting near Alexandria became less important. The main battles of the war were now happening along the Sweet Water Canal.

‘Urabi's army was completely defeated at the Battle of Tel El Kebir on September 13. Cairo then surrendered to the British the next day. The strong defenses at Kafr El Dawwar were given up without a fight to Sir Evelyn Wood on September 16. These defenses were found to be very strong. They had many lines of ditches and walls, covered paths, gun positions, and plenty of modern cannons and weapons. If the Egyptians had fought hard there, it would have been very difficult for the British to take them.

Images for kids

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |