Ahmad ibn Tulun facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ahmad ibn Tulunأحمد بن طولون |

|

|---|---|

| Emir of Egypt and Syria | |

| Rule | 15 September 868 – 10 May 884 |

| Predecessor | Azjur al-Turki (as governor for the Abbasid Caliphate in Egypt), Amajur al-Turki (as governor for the Abbasid Caliphate in Syria) |

| Successor | Khumarawayh ibn Ahmad ibn Tulun |

| Born | c. 20 September 835 (23rd Ramadan, 220 AH) Baghdad |

| Died | 10 May 884 (aged 48) al-Qata'i Abbasid Caliphate |

| Issue | al-Abbas, Khumarawayh, Rabi'ah, Shayban, and others |

| Dynasty | Tulunid dynasty |

| Father | Tulun |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

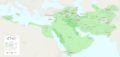

Ahmad ibn Tulun (Arabic: أحمد بن طولون, romanized: Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn; born around September 20, 835 – died May 10, 884) was a powerful ruler who founded the Tulunid dynasty. This dynasty controlled Egypt and Syria from 868 to 905.

Ahmad ibn Tulun started as a Turkic soldier. In 868, the Abbasid caliph (the Muslim ruler) sent him to Egypt as its governor. Within just four years, Ibn Tulun became almost completely independent. He took control of Egypt's money and built a large army loyal only to him. This was easier because the Abbasid court was having political problems. He also made Egypt's government work better. He improved the tax system and fixed the irrigation (water supply) system. Because of his efforts, the yearly tax money grew a lot. To show his new power, he built a new capital city called al-Qata'i, just north of the old capital, Fustat.

After 875, he had a big disagreement with al-Muwaffaq, a powerful Abbasid leader who tried to remove him. In 878, with support from the Caliph, Ibn Tulun took control of Syria and the border areas near the Byzantine Empire. While he was away in Syria, his oldest son, Abbas, tried to take power in Egypt. This led to Abbas being imprisoned, and Ibn Tulun's second son, Khumarawayh, became his chosen heir.

In 882, a top commander and the city of Tarsus turned against him. This forced Ibn Tulun to return to Syria. The Caliph, who had little power, tried to escape to Ibn Tulun's lands but was caught. Ibn Tulun then gathered religious scholars in Damascus to declare al-Muwaffaq a usurper (someone who takes power illegally). His attempt to regain Tarsus in 883 failed, and he became sick. He returned to Egypt and died in May 884. His son Khumarawayh took over.

Ibn Tulun was important because he was the first governor of a major Abbasid province to become truly independent. He also passed his power to his son. This made Egypt an independent political power again, for the first time since the ancient Ptolemaic Pharaohs. His rule influenced later Egyptian leaders, like the Ikhshidids and the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo.

Ahmad ibn Tulun's Life and Rise to Power

Early Life and Training

Ahmad ibn Tulun was born around September 20, 835, likely in Baghdad. His father, Tulun, was a Turk who was captured in 815 and sent as a gift to the Abbasid Caliph al-Ma'mun. Tulun became a respected commander in the Caliph's special guard of slave soldiers, called ghilman. Ahmad's mother was one of his father's slaves.

Young Ahmad received an excellent education. He had military training in Samarra, the new Abbasid capital. He also studied Islamic theology in Tarsus. He was known for his knowledge and his religious way of life. He was popular among other Turks, who trusted him deeply. While in Tarsus, Ibn Tulun fought in battles against the Byzantine Empire. He also met Yarjukh, a senior Turkish leader, whose daughter became his first wife. She was the mother of his eldest son, Abbas.

Later, he saved a caravan carrying a caliphal (Caliph's) envoy from raiders. This act earned him the favor of Caliph al-Musta'in. He was given money and another wife, Miyas, who became the mother of his second son, Khumarawayh. When Caliph al-Musta'in was removed from power in 866, he chose Ibn Tulun as his guard. Ibn Tulun refused an offer to harm the deposed Caliph, showing his loyalty.

Becoming Governor of Egypt

By the 9th century, powerful Turkish generals were often made governors of provinces. They could use the province's tax money for themselves and their soldiers. These generals usually stayed near the capital, Samarra, and sent deputies to govern for them. In 868, Caliph al-Mu'tazz gave Bakbak, Ibn Tulun's stepfather, control of Egypt. Bakbak then sent Ahmad ibn Tulun as his deputy and resident governor. Ahmad ibn Tulun arrived in Egypt on August 27, 868, and entered the capital, Fustat, on September 15.

At first, Ibn Tulun did not have complete control. The collection of land taxes was managed by a powerful official named Ibn al-Mudabbir. This official had been in charge since 861 and was disliked because he doubled taxes. Ibn Tulun quickly showed he wanted to be the only ruler. He refused a large gift from Ibn al-Mudabbir. For the next four years, Ibn Tulun worked to remove his rivals. In July 871, he succeeded in having Ibn al-Mudabbir moved to Syria. Ibn Tulun then took over the tax collection himself. By 872, Ibn Tulun controlled all parts of the government in Egypt. He became truly independent from the Abbasid central government.

Challenges in Egypt

When Ibn Tulun became governor, Egypt was changing. The old Arab families in Fustat lost their special rights. Power shifted to officials sent by the Abbasid court. More Muslims lived in Egypt than Coptic Christians, and the countryside was becoming more Arab and Islamic. However, parts of Upper Egypt were not fully controlled by the governor. Also, there were many revolts due to problems in the Abbasid state.

One rebel, Ibn al-Sufi, caused trouble in 869. Ibn Tulun sent an army against him, but he was hard to defeat. Another rebel, al-Umari, created his own small state around gold mines. In 874, the governor of Barqa also rebelled. Ibn Tulun had to send an army to take back the city. Re-establishing control over Barqa helped strengthen ties with Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia and parts of Algeria).

Building a Powerful Army

In 869, the Caliph ordered Ibn Tulun to fight another rebel leader in Palestine. This allowed Ibn Tulun to start buying many black African and Greek slaves to form his own army. This army, which eventually grew to about 100,000 men, became the basis of Ibn Tulun's power. It allowed him to become independent. For his personal safety, Ibn Tulun also had a special guard of ghilman from Ghur.

In 871, Ibn Tulun's father-in-law, Yarjukh, became the supervisor of Egypt. Yarjukh confirmed Ibn Tulun's position and gave him authority over Alexandria and Barqa. In 873, Ibn Tulun made his eldest son, Abbas, governor of Alexandria.

Building a New Capital: al-Qata'i

Ibn Tulun's growing power was clear when he started building a new palace city in 870. It was called al-Qata'i, located northeast of Fustat. This project was meant to be like, and even compete with, the Abbasid capital of Samarra. Like Samarra, the new city was designed with separate areas for Ibn Tulun's new army. This helped prevent problems between the soldiers and the people of Fustat. Each army unit received its own section, or "ward" (which is where the city's name comes from).

The most important building in the new city was the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, built between 878 and 880. A royal palace was next to the mosque. The city also had markets, a hospital that offered free services, and a hippodrome (a place for horse races). However, Ibn Tulun himself preferred to live in a Coptic monastery outside Fustat.

Ibn Tulun's New Government

Egypt already had a well-organized government before Ibn Tulun arrived. It had different departments, called diwans, for collecting taxes, managing mail, and overseeing public granaries. Ibn Tulun reorganized the Egyptian government to be like the Abbasid central government. Most of his officials were trained in the Caliph's court in Samarra.

Ibn Tulun's government was very centralized. He also tried to gain the support of Egypt's wealthy merchants, religious leaders, and important families. For example, a rich merchant named Ma'mar al-Jawhar was both Ibn Tulun's personal banker and the head of a secret information network. A special feature of Ibn Tulun's rule was his good relationship with Christians and Jews. When he took over Palestine, he appointed a Christian as governor of Jerusalem. This stopped the persecution of Christians and allowed churches to be renovated.

Ibn Tulun's rule brought peace and security. He created an efficient government and improved the irrigation system. This, along with good Nile floods, led to a big increase in income. By the time he died, income from land taxes alone had grown from 800,000 dinars to 4.3 million dinars. Ibn Tulun left his successor a large amount of money, about ten million dinars. He also reformed the tax system, which helped create a new class of landowners. Additional money came from trade, especially from textiles like linen.

Expanding His Power to Syria

In the early 870s, a major change happened in the Abbasid government. Prince al-Muwaffaq became the real ruler of the empire, pushing aside his brother, Caliph al-Mu'tamid. Al-Muwaffaq was busy fighting the Saffarids in the east and the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq. This gave Ibn Tulun the chance to make his position in Egypt even stronger. Ibn Tulun stayed out of the Zanj conflict and did not fully recognize al-Muwaffaq's authority.

Open conflict between Ibn Tulun and al-Muwaffaq began in 875. Ibn Tulun sent more tax money to the Caliph, al-Mu'tamid, than to al-Muwaffaq. Al-Muwaffaq was angry because he felt he deserved most of the money for his wars. He tried to replace Ibn Tulun, but no one would agree. Al-Muwaffaq sent a letter demanding Ibn Tulun's resignation, which Ibn Tulun refused. Both sides prepared for war. Ibn Tulun built a fleet and strengthened his borders and ports. Al-Muwaffaq sent an army to Syria, but it never reached Egypt. In 878, Ibn Tulun publicly showed his support for the Caliph against al-Muwaffaq.

Ibn Tulun then took action. He asked to be given command of the border regions near the Byzantine Empire. Al-Muwaffaq refused at first, but the Caliph convinced him. In 877, Ibn Tulun gained control of all of Syria and the Cilician frontier. He marched into Syria and took control of cities like Damascus and Aleppo. He also imprisoned his old rival, Ibn al-Mudabbir. Only the governor of Aleppo, Sima al-Tawil, resisted, but he was killed. Ibn Tulun continued to Tarsus to prepare for a campaign against the Byzantines.

However, news arrived from Egypt that his son Abbas, whom he had left in charge, was trying to take power. Ibn Tulun quickly left Tarsus. As he learned more, he realized Abbas was not a real threat. He decided to stay longer in Syria to strengthen his control. He fixed problems caused by the previous governor, placed troops in Aleppo, and gained the support of local tribes. He also ordered the rebuilding of the city of Akka.

In April 879, Ibn Tulun returned to Egypt. Abbas fled west but was eventually caught by Ibn Tulun's forces. After being publicly shamed, Abbas was whipped and imprisoned. Ibn Tulun then named his second son, Khumarawayh, as his new heir.

Final Years and Death

After returning from Syria, Ibn Tulun added his name to the coins minted in his lands, along with the Caliph's name. In 882, a Tulunid general and the governor of Tarsus turned against him. Ibn Tulun immediately went to Syria, taking Abbas with him. In Damascus, he received a message from Caliph al-Mu'tamid, who was trying to escape from al-Muwaffaq. If Ibn Tulun could take custody of the Caliph, it would greatly increase his power.

However, the Caliph was caught by al-Muwaffaq's agents and brought back to Samarra. This reopened the conflict between Ibn Tulun and al-Muwaffaq. Al-Muwaffaq appointed a new governor for Egypt and Syria, but it was mostly a symbolic act. Ibn Tulun gathered religious scholars in Damascus who declared al-Muwaffaq a usurper and called for a jihad (holy struggle) against him. Ibn Tulun had al-Muwaffaq denounced in Friday sermons across his lands, and al-Muwaffaq did the same to Ibn Tulun. Despite the strong words, neither side started a major military conflict.

After failing to gain control of the Caliph, Ibn Tulun turned his attention to Tarsus. He besieged the city in autumn 883, but the defenders flooded his camp, forcing him to retreat. Ibn Tulun fell ill on his way back to Egypt and was carried to Fustat. A campaign to take over the holy cities of Mecca and Medina also failed that year.

Back in Egypt, Ibn Tulun's illness worsened. People of all faiths prayed for him. Ibn Tulun died in Fustat on May 10, 884, and was buried on the slopes of the Muqattam Mountain. It is said that he left his heir a vast fortune, including many servants, soldiers, horses, and warships.

Succession and Aftermath

When Ibn Tulun died, Khumarawayh became ruler without any problems, thanks to the support of the Tulunid leaders. Ibn Tulun left his son a strong army, a stable economy, and experienced commanders. Khumarawayh managed to keep his power against Abbasid attempts to overthrow him and even gained more land. However, his lavish spending emptied the treasury. His assassination in 896 led to the quick decline of the Tulunid dynasty.

Internal conflicts weakened the Tulunids. Khumarawayh's son, Jaysh, was a weak ruler and was replaced by his brother Harun. Harun was also a weak leader. Many commanders left to join the Abbasids, whose power was growing again. Finally, in December 904, two other sons of Ibn Tulun killed their nephew and took control. This did not stop the decline. In January 905, the Abbasids easily reconquered Syria and Egypt. The victorious Abbasid troops destroyed al-Qata'i, except for the great Mosque of Ibn Tulun.

Offspring

Ahmad ibn Tulun had many children, including 17 sons and 16 daughters. Some of his notable children were:

- Sons: al-Abbas, Khumarawayh, Mudar, Rabi'ah, Shayban, and others.

- Daughters: Fatimah, Lamis, Safiyyah, Khadijah, Maymunah, Maryam, A'ishah, and others.

Legacy

Even though his dynasty was short-lived, Ibn Tulun's rule was a very important event for Egypt and the entire Islamic world. For Egypt, his reign marked a turning point. For the first time since the ancient Pharaohs, Egypt stopped being just a province ruled by a foreign power. It became a political power in its own right again.

The new realm Ibn Tulun created, which included Egypt, Syria, and parts of the Maghreb (North Africa), formed a new political zone. This area was separate from the Islamic lands further east. Egypt was the foundation of Ibn Tulun's power. He worked hard to improve its economy and create an independent government, army, and navy. These policies were continued by later Egyptian rulers, like the Ikhshidids and the Fatimids. They also used Egypt's wealth to control parts of Syria. In fact, the territory Ibn Tulun ruled in Syria was very similar to what later Egyptian rulers like Saladin and the Mamluk Sultanate controlled.

Historians see Ibn Tulun's relationship with the Abbasids as a "careful balancing act." He never completely broke away from the Caliphate and remained loyal to the Caliph himself, even though the Caliph had little real power. However, his move towards greater independence was clear throughout his rule. His conflicts with al-Muwaffaq were mainly because al-Muwaffaq wanted to control Egypt's wealth, which was needed for his wars.

In a broader sense, Ibn Tulun's role in Islamic history is seen as a sign of the Abbasid Caliphate breaking apart and local dynasties rising in the provinces. This was especially clear with Khumarawayh's succession. It was the first time that a governor, whose power came from the Caliph, was openly succeeded by his son, who claimed his right to rule through inheritance. This shows how Ibn Tulun was a key example of how ambitious slave soldiers eventually became the true masters of Islamic lands.

Images for kids

-

Spiral Minaret of the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo

-

Gold dinar of Ahmad ibn Tulun minted in Fustat in 881/2 with names of Abbasid caliph al-Mu'tamid and his Heir, al-Mufawwad

See also

In Spanish: Ahmad ibn Tulun para niños

In Spanish: Ahmad ibn Tulun para niños

- List of rulers of Egypt

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |