Zanj Rebellion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Zanj Rebellion |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

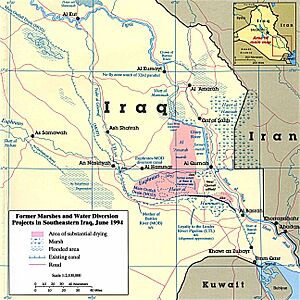

Map of Iraq and al-Ahwaz at the time of the Zanj revolt. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Zanj rebels

Allied Arabs

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Abu Ahmad al-Muwaffaq Abu al-'Abbas ibn al-Muwaffaq Musa ibn Bugha Abu al-Saj Masrur al-Balkhi Ahmad ibn Laythawayh Ibrahim ibn Muhammad |

Ali ibn Muhammad Yahya ibn Muhammad al-Bahrani Ali ibn Aban al-Muhallabi Sulayman ibn Jami' Sulayman ibn Musa al-Sha'rani Ankalay ibn Ali ibn Muhammad |

||||||

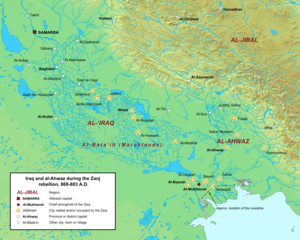

The Zanj Rebellion was a huge uprising against the Abbasid Caliphate, a powerful empire in the Middle East. It lasted for 14 years, from 869 to 883. This rebellion started near Basra in what is now southern Iraq. It was led by a man named Ali ibn Muhammad.

The revolt involved many enslaved and free people from East Africa, known as "Zanj." These people had been brought to the Middle East through the Indian Ocean slave trade. They were forced to work in harsh conditions, mainly draining salty marshes. The rebellion grew to include both enslaved and free people, including Arabs, from different parts of the Caliphate. It caused many deaths before the Abbasid government finally defeated it. Historians call it one of the most brutal uprisings of its time.

Contents

Why the Zanj Rebelled

The word "Zanj" was used by Arabs to describe people from East Africa. Many of these people were brought as slaves to southern Iraq. They were forced to work on large farms, especially in the Sawad region. Rich people from the city of Basra owned huge areas of marshland. They wanted to turn these lands into farms.

To do this, they bought many Zanj and other enslaved people. These workers were put in camps and made to clear away the salty topsoil. Others worked in salt flats near Basra. The working and living conditions for the Zanj were terrible. The work was very hard, and they were treated badly by their owners. There had been two smaller revolts before, but they failed quickly.

The Abbasid Caliphate, the government in charge, was going through a tough time. From 861, there was a period called the "Anarchy at Samarra." During this time, the government was weak. Different groups fought for control, and soldiers often rebelled because they weren't paid. Six different leaders came and went quickly. This made the government very unstable.

Because the central government was so weak, many areas became independent. This meant less tax money for the government. So, the Abbasids couldn't send enough soldiers or resources to stop the Zanj rebellion when it started. This weakness helped the rebels succeed at first.

Ali ibn Muhammad: The Leader

The leader of the Zanj Rebellion was Ali ibn Muhammad. We don't know much about his early life. Some say his family was Arab, others thought he might be Persian. Ali himself claimed to be related to Ali, the son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad. But most historians at the time said this was not true.

Ali spent some time in the capital city of Samarra. In 863, he went to Bahrayn (Eastern Arabia). There, he pretended to be a Shia Muslim and tried to start a rebellion. Many people supported him, but his revolt eventually failed. So, Ali moved to Basra in 868.

In Basra, Ali tried to use the fighting between different groups in the city to his advantage. He announced a new revolt, but no one joined him. He had to hide in the Mesopotamian Marshes. He was arrested but quickly got free. Then he went to Baghdad for a year. In Baghdad, he claimed to be a Zaydi, another branch of Shia Islam, and gained more followers.

When Ali heard about more trouble in Basra in 869, he went back. He started talking to the enslaved Black people working in the Basra marshes. He asked about their work and food. He promised them wealth and a better life if they joined him. Many people quickly joined his cause. Soon, Ali became known as Sāhib az-Zanj, which means "Chief of the Zanj."

But Ali's movement wasn't just for the Zanj. Many other people joined too. These included partly free slaves, workers, farmers, and Bedouin people from around Basra. Ali used ideas from the Kharijites, a group who believed that the best leader should rule, even if they were an enslaved person. He used Kharijite slogans on his flag and coins. But he also kept claiming to be related to Ali, the prophet's son-in-law.

The Rebellion Begins

The revolt started in September 869. It was mainly in Iraq and al-Ahwaz (modern Khuzestan Province). For the next 14 years, the Zanj fought against the stronger Abbasid army. They used guerrilla warfare, which means they used surprise attacks. They would raid towns, villages, and enemy camps, often at night. They took weapons, horses, food, and freed other enslaved people. They burned what was left to slow down the Abbasids.

As the rebellion grew, the Zanj built forts. They also created a navy to travel on the canals and rivers. They collected taxes in the areas they controlled and even made their own coins.

At first, the rebellion was focused around Basra. The Abbasid government tried to stop it, but they failed. Several towns were taken or attacked, including al-Ubulla in 870 and Suq al-Ahwaz in 871. Basra itself fell in September 871 after a long siege. The city was burned, and many people were killed.

The Abbasid leader, al-Muwaffaq, tried to fight back in 872, but he failed. The Zanj continued to attack for several years. The Abbasid army was busy fighting another enemy, Ya'qub ibn al-Layth, so they couldn't fully focus on the Zanj. This allowed the Zanj to expand their control.

By 879, the rebellion reached its furthest point. They attacked Wasit and Ramhurmuz. They even got within 50 miles of Baghdad, the capital city.

The End of the Revolt

In late 879, the Abbasid government started to win. Al-Muwaffaq sent his son, Abu al-'Abbas (who later became the caliph al-Mu'tadid), with a large army. Al-Muwaffaq himself joined the fight the next year. Over several months, the government forces pushed the rebels out of Iraq and al-Ahwaz. They drove them back to their main city, al-Mukhtarah, south of Basra.

Al-Mukhtarah was surrounded in February 881. For the next two and a half years, al-Muwaffaq offered good deals to anyone who surrendered. This convinced many rebels to give up. Al-Mukhtarah fell in August 883. Ali ibn Muhammad and most of his commanders were killed or captured. This brought the rebellion to an end. The remaining rebels either surrendered or were killed.

What Happened After

It's hard to know exactly how many people died in the Zanj Rebellion. Old writings give very different numbers, and historians today think they are too high. Some say 500,000 or even 1.5 million people died. But it's impossible to know for sure.

The rebellion caused huge damage to the areas where it took place. Cities and towns were burned. Food and supplies were taken by armies. Farms were abandoned, and trade stopped. Bridges and canals were damaged. Sometimes, there wasn't enough food or water, and there were even reports of people eating each other.

Both the rebels and the government armies looted and destroyed supplies. They also killed or executed prisoners. Historians disagree on the long-term effects. Some say the rebellion didn't change much. Others believe that the areas destroyed by the fighting never fully recovered.

The Abbasid government had to use a lot of money and soldiers to fight the Zanj. This meant they couldn't focus on other problems. For example, the governor of Egypt, Ahmad ibn Tulun, was able to create his own independent state. Also, the Saffarid rulers in the east took over several provinces without much resistance. The rebellion might have also made it harder for the Abbasids to fight the Byzantines. It might even have helped lead to the rise of another group, the Qarmatians, a few years later.

How We Know About the Zanj Rebellion

Much of what we know about the Zanj Rebellion comes from the historian al-Tabari's book, History of the Prophets and Kings. Many famous historians have studied this rebellion.

Some modern experts, like Ghada Hashem Talhami, say that we shouldn't think of "Zanj" as only meaning East Africans. She argues that the rebellion was a social uprising by poor people in the Basra area. These people included many different groups, not just enslaved people from East Africa. She points out that old writings say other groups, like Arabs and Bedouins, also joined the revolt. They don't say that the Zanj were the majority of the rebels.

Another historian, M. A. Shaban, believes it was a revolt of "blacks" (zanj), not just enslaved people. He thinks that most of the participants were free East Africans and Arabs. He argues that if it was only enslaved people, they wouldn't have had the resources to fight the Abbasid government for so long.

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |