Manuel II Palaiologos facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Manuel II Palaiologos |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |||||

Miniature portrait of Manuel II, 1407–1409

|

|||||

| Byzantine emperor | |||||

| Reign | 16 February 1391 – 21 July 1425 | ||||

| Coronation | 25 September 1373 | ||||

| Predecessor | John V Palaiologos | ||||

| Successor | John VIII Palaiologos | ||||

| Co-emperor | John VII Palaiologos (1403–1408, in Thessalonica) |

||||

| Born | 27 June 1350 Constantinople, Byzantine Empire (present day Istanbul, Turkey) |

||||

| Died | 21 July 1425 (aged 75) Constantinople, Byzantine Empire |

||||

| Spouse | Helena Dragaš | ||||

| Issue more... |

John VIII Palaiologos Theodore II Palaiologos Andronikos Palaiologos Constantine XI Palaiologos Demetrios Palaiologos Thomas Palaiologos |

||||

|

|||||

| House | Palaiologos | ||||

| Father | John V Palaiologos | ||||

| Mother | Helena Kantakouzene | ||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox | ||||

Manuel II Palaiologos (born June 27, 1350 – died July 21, 1425) was a Byzantine emperor who ruled from 1391 to 1425. He led the Byzantine Empire during a very challenging time. The empire was shrinking and faced constant threats from the Ottoman Empire.

Manuel worked hard to get help from leaders in Western Europe. He wanted to save his empire. Just before he died, he became a monk and was known as Matthew. His wife, Helena Dragaš, made sure their sons, John VIII and Constantine XI, also became emperors. The Greek Orthodox Church remembers him on July 21.

Contents

Life of Manuel II Palaiologos

Manuel II Palaiologos was the second son of Emperor John V Palaiologos. His mother was Helena Kantakouzene. His father gave him the important title of despotēs.

Manuel traveled to Western Europe in 1365 and 1370. He hoped to find support for the Byzantine Empire. From 1369, he served as governor in Thessalonica.

In 1373, his older brother, Andronikos IV Palaiologos, tried to take the throne. This failed attempt led to Manuel being named his father's heir. He became co-emperor and was crowned on September 25, 1373.

Manuel and his father lost their power twice, from 1376–1379 and again in 1390. This happened because of civil wars with Andronikos IV and his son John VII. However, Manuel defeated his nephew with help from Venice in 1390.

Even though John V got his throne back, Manuel was forced to go to the court of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I. He was an "honorary hostage" in Prousa (Bursa). During this time, Manuel had to join an Ottoman army campaign. This campaign captured Philadelphia, the last Byzantine city in Anatolia.

Seeking Help for Constantinople

In February 1391, Manuel II Palaiologos heard his father had died. He quickly left the Ottoman court. He returned to Constantinople to secure the capital. This prevented his nephew John VII from claiming the throne.

At first, the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I left Byzantium in peace. But in 1393, a large uprising happened in Bulgaria. The Ottomans stopped it, but Bayezid became very suspicious. He thought his Christian vassals were plotting against him.

Bayezid called all his Christian vassals to a meeting. He planned to kill them, but changed his mind at the last moment. This event made Manuel realize that trying to please the Ottomans was not safe. He understood that he needed help from Western Europe to save his empire.

Sultan Bayezid I then blockaded Constantinople from 1394 to 1402. Meanwhile, a Christian army, led by the Hungarian King Sigismund, tried to fight the Ottomans. This army was defeated at the Battle of Nicopolis on September 25, 1396. Manuel II had sent 10 ships to help them.

In October 1397, Manuel's uncle, Theodore Kantakouzenos, went to the court of Charles VI of France. He carried letters from the Emperor asking for military help. Charles also gave money for them to visit King Richard II of England in April 1398. They hoped to get more aid, but Richard II was busy with problems in his own country.

The two nobles returned home with the French Marshal Jean II Le Maingre. He brought 1,200 men on six ships to help Manuel II. The Marshal encouraged Manuel to travel to Western Europe himself. He wanted Manuel to personally ask for help against the Ottoman Empire.

After five years of siege, Manuel II left Constantinople. He put his nephew in charge of the city. A French group of 300 soldiers, led by Seigneur Jean de Châteaumorand, helped defend the city. Manuel then began a long trip abroad with the Marshal and 40 other people.

Emperor's Journey to the West

On December 10, 1399, Manuel II sailed to the Morea. He left his wife and children there with his brother Theodore I Palaiologos. This was to protect them from his nephew.

He landed in Venice in April 1400. Then he traveled through Padua, Vicenza, and Pavia. He reached Milan, where he met Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti and his friend Manuel Chrysoloras. Later, he met King Charles VI of France on June 3, 1400. While in France, Manuel II continued to contact other European kings.

A writer named Michel Pintoin described the visit to Paris:

Then, the king raised his hat, and the emperor raised his imperial cap – he had no

hat – and both greeted one another in the most honourable way. When he had welcomed [the emperor], the king accompanied him into Paris, riding side by side. They were followed by the Princes of the Blood who, once the banquet in the royal palace finished, escorted [the emperor] to the lodgings which had been prepared for him in the Louvre castle].

In December 1400, Manuel sailed to England to meet Henry IV of England. Henry IV welcomed him on December 21 at Blackheath. Manuel II was the only Byzantine emperor ever to visit England. He stayed at Eltham Palace until mid-February 1401. A joust was held in his honor. He also received £2,000, which he confirmed with his own golden bull.

Thomas Walsingham wrote about Manuel II's visit to England:

At the same time the Emperor of Constantinople visited England to ask for help against the Turks. The king with an imposing retinue, met him at Blackheath on the feast of St Thomas [21 December], gave so great a hero an appropriate welcome and escorted him to London. He entertained him there royally for many days, paying the expenses of the emperor's stay, and by grand presents showing respect for a person of such eminence.

Another writer, Adam of Usk, also reported:

On the feast of St Thomas the apostle [21 December], the emperor of the Greeks visited the king of England in London to seek help against the Saracens, and was honourably received by him, staying with him for two whole months at enormous expense to the king, and being showered with gifts at his departure. This emperor and his men always went about dressed uniformly in long robes cut like tabards which were all of one colour, namely white, and disapproved greatly of the fashions and varieties of dress worn by the English, declaring that they signified inconstancy and fickleness of heart. No razor ever touched the heads or beards of his priests. These Greeks were extremely devout in their religious services, having them chanted variously by knights or by clerics, for they were sung in their native tongue. I thought to myself how sad it was that this great Christian leader from the remote east had been driven by the power of the infidels to visit distant islands in the west in order to seek help against them.

Manuel II wrote a letter to his friend Manuel Chrysoloras about his visit to England:

Now what is the reason for the present letter? A large number of letters have come to us from all over bearing excellent and wonderful promises, but most important is the ruler with whom we are now staying, the king of Britain the Great, of a second civilized world, you might say, who abounds in so many good qualities and is adorned with all sorts of virtues. His reputation earns him the admiration of people who have not met him, while for those who have once seen him, he proves brilliantly that Fame is not really a goddess, since she is unable to show the man to be as great as does actual experience. This ruler, then, is most illustrious because of his position, most illustrious too, because of his intelligence; his might amazes everyone, and his understanding wins him friends; he extends his hand to all and in every way he places himself at the service of those who need help. And now, in accord with his nature, he has made himself a virtual haven for us in the midst of a twofold tempest, that of the season and that of fortune, and we have found refuge in the man himself and his character. His conversation is quite charming; he pleases us in every way; he honours us to the greatest extent and loves us no less. Although he has gone to extremes in all he has done for us, he seems almost to blush in the belief—in this he is alone—that he might have fallen considerably short of what he should have done. This is how magnanimous the man is.

Manuel II returned to France hoping for significant help and money for Constantinople. He sent groups with relics to other leaders. These included Pope Boniface IX, Queen Margaret I of Denmark, and kings of Aragon and Navarre. He hoped to get more assistance. He finally left France on November 23, 1402, and returned to Constantinople in June 1403.

Later Ottoman Conflicts

The Ottomans, led by Bayezid I, were badly defeated by Timur at the Battle of Ankara in 1402. Bayezid I's sons then fought among themselves for power. This period was called the Ottoman Interregnum. During this time, John VII managed to get back some Byzantine lands. These included the European coast of the Sea of Marmara and Thessalonica. This was part of the Treaty of Gallipoli.

When Manuel II returned home in 1403, his nephew gave back control of Constantinople. As a reward, John VII became governor of the newly recovered Thessalonica. The treaty also helped Byzantium regain other areas. These included Mesembria, Varna, and parts of the Marmara coast.

Manuel II stayed in touch with Venice, Genoa, Paris, and Aragon. He sent his envoy, Manuel Chrysoloras, in 1407–8. He was still trying to form a group to fight the Ottomans.

On July 25, 1414, Manuel left Constantinople with a fleet. He stopped at Thasos, an island threatened by a local lord. It took him three months to bring the island back under imperial control. After this, he continued to Thessalonica. His son Andronicus, who governed the city, welcomed him warmly.

In the spring of 1415, Manuel and his soldiers went to the Peloponnese. He arrived at the port of Kenchreai on March 29. Manuel II Palaiologos used his time there to strengthen the defenses of the Despotate of Morea. This was a part of the Byzantine Empire that was actually growing.

Manuel oversaw the building of the Hexamilion. This was a six-mile wall across the Isthmus of Corinth. It was built to protect the Peloponnese from the Ottomans.

Manuel II had a good relationship with Mehmed I (1402–1421), who won the Ottoman civil war. However, Manuel tried to get involved in the next Ottoman succession dispute. This led to a new attack on Constantinople by Murad II (1421–1451) in 1422.

During his last years, Manuel II gave most of his duties to his son and heir, John VIII Palaiologos. He traveled to the West again, this time to King Sigismund of Hungary. He stayed for two months at Sigismund's court in Buda. Sigismund had been defeated by the Turks in 1396. He was open to fighting the Ottoman Empire again. However, the Hussite wars in Bohemia meant he couldn't rely on Czech or German armies. Hungarian armies were needed to protect their own kingdom.

Sadly, Manuel returned home from Hungary without the help he needed. In 1424, he and his son had to sign a bad peace treaty with the Ottoman Turks. This treaty forced the Byzantine Empire to pay tribute to the Sultan.

Death

Manuel II suffered a stroke on October 1, 1422, which paralyzed him. But his mind remained clear, and he continued to rule for three more years. He spent his last days as a monk, taking the name Matthew. He died on July 21, 1425, at the age of 75. He was buried at the Pantokrator Monastery in Constantinople.

Writings

Manuel II wrote many different kinds of works. These included letters, poems, and a biography of a saint. He also wrote about theology and rhetoric. He wrote an epitaph for his brother Theodore I Palaiologos. He also wrote a "mirror of princes" for his son and heir, John. This "mirror of princes" is very important. It is the last example of this type of book given to us by the Byzantines. These books offered advice to future rulers.

Family

Manuel II Palaiologos and his wife, Helena Dragas, had several children. Helena was the daughter of the Serbian prince Constantine Dragas. Their children included:

- A daughter (her name is not mentioned).

- Constantine Palaiologos (born around 1393/8, died before 1405).

- John VIII Palaiologos (December 18, 1392 – October 31, 1448). He became Byzantine emperor from 1425–1448.

- Andronikos Palaiologos, Lord of Thessalonica (died 1429).

- A second daughter (her name is not mentioned).

- Theodore II Palaiologos, Lord of Morea (died 1448).

- Michael Palaiologos (born 1406/7, died 1409/10 from the plague).

- Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos (February 8, 1405 – May 29, 1453). He was a Despotēs in the Morea and later the last Byzantine emperor, from 1448–1453.

- Demetrios Palaiologos (around 1407–1470). He was a Despotēs in the Morea.

- Thomas Palaiologos (around 1409 – May 12, 1465). He was a Despotēs in the Morea.

Gallery

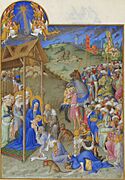

- Manuel II as depicted in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

See also

In Spanish: Manuel II Paleólogo para niños

In Spanish: Manuel II Paleólogo para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |