Thomas Palaiologos facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Thomas Palaiologos |

|

|---|---|

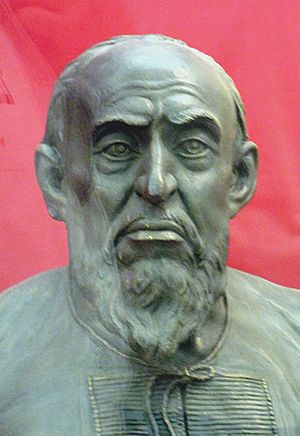

Thomas, detail from the Pintoricchio fresco of Pius II's arrival at Ancona, in the Siena Cathedral

|

|

| Despot of the Morea | |

| Reign | 1428–1460 (claimed in exile until 12 May 1465) |

| Predecessor | Theodore II Palaiologos (alone) |

| Successor | Andreas Palaiologos (titular) |

| Co-rulers |

|

| Born | 1409 Constantinople |

| Died | 12 May 1465 (aged 56) Rome |

| Burial | St. Peter's Basilica, Rome |

| Spouse | Catherine Zaccaria |

| Issue |

|

| Dynasty | Palaiologos |

| Father | Manuel II Palaiologos |

| Mother | Helena Dragaš |

| Religion | Catholic/Orthodox |

| Signature | |

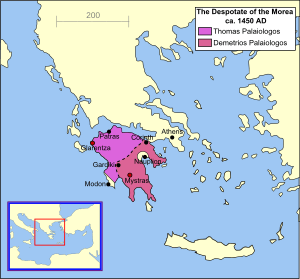

Thomas Palaiologos (Greek: Θωμᾶς Παλαιολόγος; 1409 – 12 May 1465) was a ruler known as the Despot of the Morea. He held this title from 1428 until 1460. Even after losing his lands, he continued to claim the title for five more years. Thomas was the younger brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos, who was the very last Byzantine emperor.

In 1428, Thomas became Despot of the Morea. His older brother, Emperor John VIII Palaiologos, appointed him. Thomas joined his brothers Theodore and Constantine, who were already ruling the Morea. Theodore was not always easy to work with. However, Thomas and Constantine worked well together. They made the despotate stronger and bigger. In 1432, Thomas married Catherine Zaccaria. She was the heir to the Principality of Achaea. This marriage helped bring the last parts of that old crusader state under Byzantine control.

In 1449, Thomas supported his brother Constantine to become emperor. This happened even though their brother Demetrios wanted the throne. After Constantine became Emperor Constantine XI, Demetrios was sent to rule the Morea with Thomas. But the two brothers often argued and found it hard to cooperate. After Constantinople fell in 1453, the Byzantine Empire ended. The Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II allowed Thomas and Demetrios to keep ruling the Morea. They had to pay tribute to him. Thomas hoped to make the Morea a place to start a fight to bring back the empire. He wanted help from the Pope and Western Europe. But his constant arguments with Demetrios, who sided with the Ottomans, led Mehmed to invade and conquer the Morea in 1460.

Thomas, his wife Catherine, and their three younger children escaped. They went to the Venetian city of Methoni and then to Corfu. Catherine and the children stayed there. Thomas traveled to Rome. He hoped to get support for a crusade to get his lands back. Pope Pius II welcomed him and helped him. But Thomas's hopes of getting the Morea back never came true. He died in Rome on May 12, 1465. After his death, his oldest son Andreas continued to claim his titles. Andreas also tried to gather support to restore the fallen despotate and the Byzantine Empire.

Contents

Thomas's Life Story

Becoming a Despot

The Byzantine Empire was slowly breaking apart in the 1300s. Emperors of the Palaiologan family found a way to keep their lands. They gave parts of their empire to their sons. These sons were called "despots." They would defend and govern these areas. Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos (who ruled from 1391–1425) had six sons who grew up.

Manuel's oldest son, John, was chosen to be the next emperor. His second son, Theodore, became Despot of the Morea. The third son, Andronikos, became Despot of Thessaloniki in 1408. He was only eight years old. Manuel's younger sons, Constantine, Demetrios, and Thomas (the youngest, born in 1409), stayed in Constantinople. There wasn't enough land left to give them their own areas to rule. These younger children were called Porphyrogennetos. This means "born in the purple," or born in the imperial palace while their father was emperor.

The Palaiologos brothers did not always get along. John and Constantine seemed to be good friends. But Constantine, Demetrios, and Thomas had a harder time. Their relationships were tested in 1428. John, now Emperor John VIII, made Constantine Despot of the Morea. His brother Theodore refused to give up his role. So, for the first time, two imperial family members ruled the despotate. Soon after, Thomas, who was 19, also became Despot of the Morea. This meant the Morea was split into three smaller areas.

Theodore did not leave the capital, Mystras, for Constantine or Thomas. Instead, Theodore gave Constantine lands across the Morea. These included the northern port of Aigio, and towns in Laconia and Messenia. Constantine made Glarentza his capital. Thomas received lands in the north. His base was the castle of Kalavryta.

Ruling the Morea under the Empire

Making the Morea Stronger

Soon after becoming despots, Constantine, Thomas, and Theodore decided to work together. They wanted to capture the important port of Patras in the northwest Morea. This city was ruled by a Catholic Archbishop. The campaign failed, perhaps because Theodore was not fully committed. This was Thomas's first experience in war. Constantine later captured Patras on his own. This ended 225 years of foreign control there.

Thomas also helped gain new lands. For years, Thomas and Constantine had been taking back parts of the Principality of Achaea. This was a state created by crusaders in 1204. It once ruled almost the entire peninsula. Thomas finally ended this principality. He married Catherine Zaccaria, the daughter and heir of its last prince, Centurione II Zaccaria. When Centurione died in 1432, Thomas gained control of all his remaining lands. By the 1430s, Thomas and Constantine had brought almost the entire Peloponnese back under Byzantine control. This was the first time since 1204. Only a few port towns held by the Republic of Venice remained outside their control.

Murad II, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, was worried. The Ottomans controlled most of the old Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire and the Morea were like vassal states, meaning they had to obey the Sultan. In 1431, Turahan Bey, a Turkish general, sent troops south. They destroyed the Morea's main defense, the Hexamilion wall. This was a reminder to the despots that they were the Sultan's subjects.

In March 1432, Constantine made a new land agreement with Thomas. Theodore and John VIII likely approved it. Thomas gave his fortress Kalavryta to Constantine. Constantine made it his new capital. In return, Thomas received Elis, which became his new capital. Relations between the three despots seemed good in 1432. But they soon became difficult. John VIII had no sons to take his place. So, one of his four surviving brothers would become emperor. John VIII preferred Constantine. Thomas accepted this choice, as he got along well with Constantine. But Theodore, who was older, did not like it.

In November 1443, Constantine gave Selymbria to Theodore. In return, Theodore left his role as Despot of the Morea. This made Constantine and Thomas the only Despots of the Morea. This move brought Theodore closer to Constantinople. It also made Constantine the ruler of the Morea's capital, Mystras. He became one of the most powerful men in the small empire. With Theodore and Demetrios out of the way, Constantine and Thomas hoped to make the Morea stronger. It was now the cultural center of the Byzantine world. They wanted it to be a safe and self-sufficient principality.

Turkish Attacks and Constantine XI's Rule

As part of their plan to strengthen the despotate, the brothers rebuilt the Hexamilion wall. The Turks had destroyed it in 1431. They finished restoring the wall in March 1444. But the Turks destroyed it again in 1446. This happened after Constantine tried to expand his control north. He refused the sultan's demand to take down the wall. Constantine and Thomas were determined to hold the wall. They gathered all their forces, about twenty thousand men, to defend it.

Despite their efforts, the battle at the wall in 1446 was a huge Turkish victory. Constantine and Thomas barely escaped. Turahan Bey was sent south to attack Mystras. Sultan Murad II led his forces in the north. Turahan failed to take Mystras. But Murad did not want to conquer the Morea at that time. He just wanted to scare them. The Turks soon left the peninsula, leaving it damaged and with fewer people. Constantine and Thomas had no choice but to accept Murad as their lord. They had to pay him tribute. They also promised never to rebuild the Hexamilion wall.

Their former co-despot Theodore died in June 1448. On October 31 of the same year, Emperor John VIII passed away. The possible next emperors were Constantine, Demetrios, and Thomas. John had not officially named an heir. But everyone knew he preferred Constantine. In the end, their mother, Helena Dragaš, who also preferred Constantine, made the decision. Thomas did not want the throne. Demetrios certainly did. Both hurried to Constantinople. They arrived before Constantine. Many people favored Demetrios because he was against uniting with the Western Church. But Helena kept her right to be regent until Constantine arrived. This stopped Demetrios from taking the throne. Thomas accepted Constantine's appointment. Demetrios soon joined in proclaiming Constantine as the new emperor.

The Byzantine historian George Sphrantzes then told Sultan Murad II. The Sultan also accepted Constantine's rule. To get Demetrios away from the capital, Constantine made him Despot of the Morea. Demetrios would rule with Thomas. Demetrios was given Mystras. He mainly ruled the southern and eastern parts of the despotate. Thomas ruled Corinthia and the northwest. He used Patras or Leontari as his capital.

In 1451, Sultan Murad II died. He was old and tired and had given up on conquering Constantinople. His young and energetic son, Mehmed II, became sultan. Mehmed was determined to take Constantinople. In 1452, as the Ottomans prepared to besiege Constantinople, Constantine XI sent an urgent message to the Morea. He asked one of his brothers to bring their forces to help defend the city. To stop aid from the Morea, Mehmed II sent Turahan Bey to attack the peninsula again. The Turkish attack was stopped by an army led by Matthaios Asan. He was Demetrios's brother-in-law. But this victory came too late to help Constantinople.

Ruling the Morea under Ottoman Control

Early Years under Ottoman Rule

Constantinople finally fell on May 29, 1453. Constantine XI died defending it. This marked the end of the Byzantine Empire. After Constantinople fell, a big worry for the new Ottoman rulers was that one of Constantine XI's relatives might try to reclaim the empire. Luckily for Mehmed II, the two despots in the Morea were not a big threat. They were allowed to keep their titles and lands. Thomas and Demetrios sent messengers to the Sultan in Adrianople. The Sultan did not demand any land. He only asked that the despots pay an annual tribute of 10,000 ducats.

Because the Morea was allowed to continue, many Byzantine refugees fled there. It became a kind of Byzantine government-in-exile. Some important refugees even suggested making Demetrios, the older brother, the Emperor of the Romans. Both Thomas and Demetrios might have thought about making their small despotate a place to start a fight to bring back the empire. The despotate had fertile and wealthy land. For a moment, it seemed possible the empire could live on in the Morea. However, Thomas and Demetrios could never work together. They spent most of their time fighting each other instead of preparing for a struggle against the Turks. Thomas had lived most of his life in the Morea. Demetrios had lived mostly elsewhere. So, the two brothers hardly knew each other.

Soon after Constantinople fell, a revolt started in the Morea. Many Albanian immigrants in the region were unhappy with the local Greek landowners. The Albanians had respected earlier despots like Constantine and Theodore. But they disliked the two current despots. Without a central authority from Constantinople, they saw a chance to take control. In Thomas's part of the despotate, the rebels chose John Asen Zaccaria as their leader. He was the son of the last Prince of Achaea. In Demetrios's part, the leader was Manuel Kantakouzenos.

The despots had no hope of defeating the Albanians alone. They asked the Ottomans for help. Mehmed II did not want the despotate to fall into Albanian hands. He wanted to keep control. So, he sent an army to stop the rebellion in December 1453. The rebellion was not fully crushed until October 1454. That's when Turahan Bey arrived to help the despots. In return for the help, Mehmed demanded a higher tribute. Thomas and Demetrios now had to pay 12,000 ducats each year.

Hopes for Western Help

Neither brother could pay the amount the Sultan demanded. They also disagreed on what to do. Demetrios, who was probably more realistic, had mostly given up on Christian help from the West. He thought it was best to try and please the Turks. But Thomas still hoped that the Pope might call for a crusade to bring back the Byzantine Empire. Thomas's hopes were not silly. The fall of Constantinople had shocked Western Europe.

In September 1453, Pope Nicholas V issued a special order. It called on Christians in the West to join a crusade to take back Constantinople. Many people were excited. Some of Europe's most powerful rulers promised to join. These included Philip the Good of Burgundy in February 1454. Also, Alfonso the Magnanimous of Aragon and Naples joined in November 1455. Alfonso promised to lead 50,000 men and 400 ships against the Ottomans. In Frankfurt, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III gathered German princes. He suggested sending 40,000 men to Hungary. The Ottomans had suffered a big defeat there in 1456. If these forces had worked together, Ottoman control of the Balkans would have been in serious danger.

The Ottomans had helped the despots in the Albanian uprising. But the chance of Western help to restore Byzantine land was too tempting to resist. In 1456, Thomas sent John Argyropoulos to the West. His mission was to discuss possible aid for the Morea. Argyropoulos was a good choice. He had strongly supported the Council of Florence. This meant he was well received by Pope Nicholas V's successor, Pope Callixtus III, in Rome. From Rome, Argyropoulos also visited Milan, England, and France. More messengers were sent to Aragon and Venice. Thomas hoped to find refuge in Venetian territory if the Ottomans attacked the Morea. A crusade seemed so close that even Demetrios, who usually disliked Westerners, softened his stance. He sent his own messengers.

Civil War and the Fall of the Morea

In the end, no crusade ever started against the Ottomans. The two despots believed help would arrive. They also couldn't pay. So, they had not paid their annual tribute to the Ottomans for three years. With no money coming from the Morea, and the threat of Western help, Mehmed lost his patience. The Ottoman army marched from Adrianople in May 1458. They entered the Morea. The only real resistance was at Corinth, in Demetrios's area. Mehmed left his cannons to attack Corinth. He then took most of his army to conquer the northern parts of the despotate, which was Thomas's land. Corinth finally surrendered in August. Several northern cities had already given up. Mehmed punished the Morea severely.

The land ruled by the two brothers was greatly reduced. Corinth, Patras, and much of the northwest were taken by the Ottoman Empire. Turkish governors were put in charge. The Palaiologoi were only allowed to keep the south, including Mystras. This was on the condition that they paid their annual tribute to the sultan.

Almost as soon as Mehmed left the Morea, the two brothers started arguing again. Mehmed's victory only made Thomas and Demetrios dislike each other more. Demetrios became even more pro-Ottoman. Mehmed had promised to marry his daughter Helena. Thomas, however, hoped more and more for Western help. The areas Mehmed had taken were almost all the land Thomas had ruled, including his capital of Patras. In January 1459, Thomas rebelled against Demetrios and the Ottomans. He joined with some Albanian lords. They captured the fortress of Kalavryta and much of central Morea. They also attacked Kalamata and Mantineia, which were Demetrios's fortresses. Demetrios responded by taking Leontari. He asked for help from the Turkish governors in the northern Morea. Many attempts were made to make peace between the brothers. Mehmed even ordered the Bishop of Lacedaemon to make them promise to keep the peace. But any truce lasted only a short time. Many Byzantine nobles in the Morea watched in horror as the civil war continued. George Sphrantzes described the conflict:

Both brothers fought against each other with all their resources. Lord Demetrios rested his hopes on the friendship and help of the sultan, and on his claim that his subjects and castles had been wronged, while Lord Thomas relied on the fact that his opponent had committed perjury and that he was waging war against the impious.

Demetrios had more soldiers and resources. But Thomas and the Albanians were able to ask the West for help. After a successful small battle against the Ottomans, Thomas sent 16 captured Turkish soldiers to Rome. He also sent some of his guards. He wanted to convince the Pope that he was fighting a holy war against the Muslims. His plan worked. The Pope sent 300 Italian soldiers to help Thomas. With these new soldiers, Thomas gained the upper hand. It looked like Demetrios was about to be defeated. He had retreated to Monemvasia. He sent Matthaios Asan to Adrianople to beg Mehmed for help. Thomas's requests to the West were a real threat to the Ottomans. This threat grew even bigger with the support of Cardinal Bessarion. He was a Byzantine refugee who had escaped years earlier. Pope Pius II held a meeting in 1459 in Mantua. He sent Bessarion and others to preach for a crusade against the Ottomans across Europe.

Mehmed decided that the only way to control Greece was to destroy the despotate. He would take it directly into his empire. The sultan gathered his army again in April 1460. He led it himself, first to Corinth, then to Mystras. Demetrios had supposedly been on the sultan's side. But Mehmed invaded Demetrios's territory first. Demetrios surrendered to the Ottomans without a fight. He feared punishment and had already sent his family to safety in Monemvasia. Mystras fell to the Ottomans on May 29, 1460. This was exactly seven years after Constantinople's fall. The few places in the Morea that dared to resist were destroyed. The men were killed, and the women and children were taken away. Many Greek refugees escaped to Venetian lands like Methoni and Koroni. The Morea was slowly brought under control. The last resistance was led by Constantine Graitzas Palaiologos, a relative of Thomas and Demetrios. This happened at Salmenikon in July 1461.

Life in Exile

When Thomas first heard of Mehmed's invasion, he went to Mantineia. He wanted to see how the invasion would unfold. But it became clear that the Ottomans were marching towards Leontari. They would soon arrive outside Mantineia. So, Thomas, his group (including other Greek nobles like George Sphrantzes), his wife Catherine, and his children Andreas, Manuel, and Zoe fled to Methoni. Thomas and his companions then fled to the island of Corfu. They arrived there on Venetian ships on July 22, 1460.

Catherine and the children stayed on Corfu. But the island was only a temporary safe place for Thomas. The local government did not want him to stay too long. They feared making the Ottomans angry. Thomas was unsure where to go next. He tried to travel to Ragusa, but the city's leaders refused his arrival. Around the same time, Mehmed II sent messengers to Thomas. He asked Thomas to make a "treaty of friendship." He promised him lands if he returned to Greece. Thomas was unsure what to do. He sent messengers to both Mehmed and the Pope. The messenger to Mehmed found the sultan at Veria. Despite the sultan's words, the messenger and his group were immediately arrested and chained.

A few days later, the messenger was freed. He returned to Thomas at Corfu with a message. Thomas had to come to Mehmed in person, or send some of his children. Because of this, Thomas decided he had no choice. The West was his only option. On November 16, 1460, he left his wife and children on Corfu. He sailed for Italy, landing in Ancona. In March 1461, Thomas arrived in Rome. He hoped to convince Pope Pius II to call for a crusade. As the brother of the last Byzantine emperor, Thomas was the most important exiled ruler. He was one of many Christians who escaped the Balkans during the Ottoman conquest.

In Rome, Thomas met with Pius II. The Pope gave him the Golden Rose. Thomas stayed in the Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sassia. He received a pension of 300 ducats each month (3600 annually). Besides the Pope's money, Thomas also got 200 ducats a month from the cardinals. The Republic of Venice gave him 500 ducats. Venice also asked him not to return to Corfu. They didn't want to affect their difficult relationship with the Ottomans. Thomas's many followers thought the money was barely enough for the despot. It was certainly not enough to support them too. The Pope recognized Thomas as the rightful Despot of the Morea. He was also seen as the true heir to the Byzantine Empire. However, Thomas never claimed the title of emperor.

While in Rome, Thomas was known for his "tall and handsome appearance." He served as the model for the statue of Saint Paul. This statue still stands in front of the St. Peter's Basilica today. On April 12, 1462, Thomas gave the supposed skull of Saint Andrew the Apostle to Pius II. This was a very valuable relic that Byzantines had held for centuries. Pius received the skull from Cardinal Bessarion at the Ponte Milvio. The ceremony was seen as Andrew returning to his relatives, the Romans. It is shown on Pius II's grave.

In the 1460s, plans for a crusade against the Ottomans began again. Pius II had made taking back Constantinople one of his main goals. His 1459 meeting at Mantua had secured promises for an army of 80,000 men. These men would come from various Western European powers. Naval support was secured in 1463. Venice officially declared war on the Ottomans. This was because the Turks had attacked their lands in Greece. In October 1463, Pius II formally declared war on the Ottoman Empire. Mehmed had refused his suggestion to convert to Christianity. Many Balkan exiles in the West were happy to live quietly. But Thomas hoped to get back control of Byzantine territory. So, he strongly supported the crusade plans.

In early 1462, Thomas left Rome to travel around Italy. He wanted to gather support for a crusade. He carried letters from the Pope. Pius II described him as "a prince who was born to the illustrious and ancient family of the Palaiologoi... a man who is now an immigrant, naked, robbed of everything except his lineage." Like his father Manuel II and his brother John VIII, Thomas had a certain royal charm and good looks. This helped his appeals. The ambassador from Mantua in Rome described him as "a handsome man with a fine, serious look about him and a noble and quite lordly bearing." Milanese ambassadors who met him in Venice wrote that Thomas was "as dignified as any man on Earth can be."

Of the many courts Thomas visited, only Venice strongly objected to his appeal. The local leaders made it clear they wanted nothing to do with him. They made Thomas leave the city. They also sent ambassadors to Rome. They asked that he not join the expedition. They said his presence would "produce terrible and incongruous scandals." Venice might have been angry with Thomas for attacking Venetian lands when he was a despot. Or it could be because his arguments with his brother Demetrios led to the fall of the Morean despotate. Despite Thomas's hopes, no expedition set out for Greece. When the army was ready to sail in 1464, Pius II traveled to Ancona to join the crusade. But he died there on August 15. Without Pius II's leadership, the crusade quickly fell apart. All the ships returned home.

Thomas's wife died in August 1462. He then called his children, who were still in Corfu, to Rome. But they only arrived in the city after Thomas had died on May 12, 1465. Thomas had been largely forgotten by the Roman elite after Pius II's death in 1464. However, he was buried with honor in the St. Peter's Basilica. His grave survived the destruction of the Palaiologan emperors' tombs in Constantinople by the Ottomans. Modern attempts to find his grave in the Basilica have not been successful so far.

Thomas's Children

It is generally believed that Thomas had four children with Catherine Zaccaria. This number comes from George Sphrantzes. These four children were:

- Helena Palaiologina (1431 – November 7, 1473): She was the older of the two daughters. Helena married Lazar Branković, who was the son of Đurađ Branković, Despot of Serbia. By the time the Morea fell, Helena had already moved to Smederevo with her husband. He became the Despot of Serbia in 1456. Lazar died in 1458. Helena was left to care for their three daughters. In 1459, Mehmed II invaded Serbia and ended the despotate. But Helena was allowed to leave the country. After some time in Ragusa, she moved to Corfu. She lived there with her mother and siblings. Later, Helena became a nun. She lived on the island of Lefkada, where she died in November 1473. Helena had many descendants through her three daughters. But none of them carried the Palaiologos name.

- Zoe Palaiologina (c. 1449 – April 7, 1503): She was the younger daughter of Thomas and Catherine. Pope Sixtus IV arranged for Zoe to marry Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow, in 1472. The Pope hoped to convert the Russians to Roman Catholicism. But the Russians did not convert. The marriage followed Eastern Orthodox traditions. Zoe was called "Sophia" in Russia. Her marriage to Ivan III helped Moscow claim to be the "third Rome." This meant it was the spiritual successor to the Byzantine Empire. Zoe and Ivan III had several children. They, in turn, had many descendants. None carried the Palaiologos name. But many used the double-headed eagle symbol of Byzantium. Ivan the Terrible, Russia's first crowned tsar, was Sophia's grandson.

- Andreas Palaiologos (January 17, 1453 – June 1502): He was the older of the two sons. Andreas lived most of his life in Rome. He survived on a papal pension that slowly decreased. After Thomas's death, the Pope and others in Italy recognized Andreas as the rightful heir to the Despotate of the Morea. He later also claimed the title Imperator Constantinopolitanus ("Emperor of Constantinople"). He hoped to one day restore the fallen Byzantine Empire. He tried to organize an expedition to restore the empire in 1481. But his plans failed. He later gave his rights to the imperial title to Charles VIII of France. He hoped Charles would fight against the Turks. Andreas died poor in Rome. It is not certain if he had any children. His will stated that his titles should go to the Catholic Monarchs in Spain. However, they never used them.

- Manuel Palaiologos (January 2, 1455 – before 1512): He was the youngest of the four children. Manuel lived in Rome and relied on Papal money, much like his brother. As the pension got smaller, and Manuel had no titles to sell, he traveled Europe. He looked for someone to hire him as a soldier. He didn't find good offers. So, Manuel surprised everyone. He traveled to Constantinople in 1476. He asked Sultan Mehmed II for mercy. The Sultan kindly welcomed him. Manuel married an unknown woman and stayed in Constantinople for the rest of his life. Manuel had two sons. One died young. The other converted to Islam. His fate is not known for sure.

|

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |