Andreas Palaiologos facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Andreas Palaiologos |

|

|---|---|

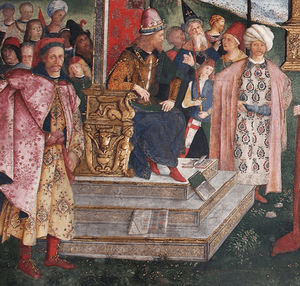

Probable portrait of Andreas as part of Pinturicchio's St Catherine's Disputation (1491) in the Hall of the Saints in the Borgia Apartments, Vatican Palace

|

|

| Emperor of Constantinople (titular) |

|

| 1st reign | 13 April 1483 – 6 November 1494 |

| Predecessor | Constantine XI Palaiologos |

| Successor | Charles VIII of France (purchased titles) |

| 2nd reign | 7 April 1498 – June 1502 |

| Predecessor | Charles VIII of France |

| Despot of the Morea (titular) |

|

| Reign | 12 May 1465 – June 1502 |

| Predecessor | Thomas Palaiologos |

| Successor | Fernando Palaiologos Constantine Arianiti (both self-proclaimed) |

| Born | 17 January 1453 Morea |

| Died | June 1502 (aged 49) Rome |

| Burial | St. Peter's Basilica, Rome |

| Spouse | Caterina |

| Dynasty | Palaiologos |

| Father | Thomas Palaiologos |

| Mother | Catherine Zaccaria |

Andreas Palaiologos (born January 17, 1453 – died June 1502) was an important figure in the history of the Byzantine Empire. He was the oldest son of Thomas Palaiologos, who was the ruler (called a Despot) of a region in Greece called the Morea. Andreas's uncle was Constantine XI Palaiologos, the very last Byzantine Emperor.

After his father passed away in 1465, Andreas became the leader of the Palaiologos family. He was seen as the rightful heir to the old Byzantine throne. From 1483 onwards, he also claimed the title "Emperor of Constantinople". Andreas hoped to one day bring back the empire of his family. He married a woman from Rome named Caterina.

Andreas lived in Rome and faced many money problems. He traveled around Europe, trying to find a ruler who would help him take back Constantinople from the Ottomans. However, he didn't get much support. He even tried to organize an army to cross the Adriatic Sea and fight the Ottomans, but it didn't happen.

To get money, Andreas sold his rights to the Byzantine crown in 1494 to Charles VIII of France. Charles was planning a crusade against the Ottomans. The deal was that Charles would help Andreas get back the Morea. When Charles died in 1498, Andreas claimed his imperial titles again. He died in Rome in 1502, still struggling financially, and was buried in St. Peter's Basilica.

Contents

The Byzantine Empire's End

The Last Imperial Family

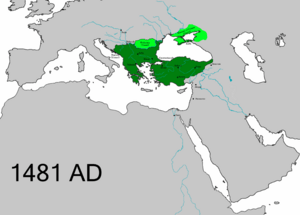

The Palaiologos family was the final ruling family of the Byzantine Empire. They ruled from 1259 until the empire fell in 1453. By the 1400s, the Byzantine Empire was shrinking fast. The Ottoman Turks had taken over huge parts of its land.

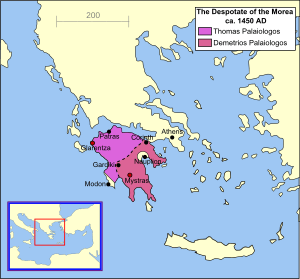

By the 15th century, the Byzantine Empire was mostly just its capital city, Constantinople, and a region called the Peloponnese (which included the Morea). The emperors tried to keep their remaining lands safe by giving parts of them to their sons or brothers. These family members were called "despots" and were meant to defend and govern these areas.

In 1428, Andreas's father, Thomas Palaiologos, became the Despot of the Morea. He ruled this rich province with his older brothers, Theodore and Constantine. Constantine later became Emperor Constantine XI, the last emperor. These brothers worked to bring the entire Peloponnese under Byzantine control.

Seeking Help from the West

As their empire was falling apart, the Orthodox Palaiologos emperors looked to Catholic Europe for military help. They hoped that if they could convince the popes that they were true Christians, the Pope would send large armies to save their empire from the Ottomans.

Andreas's great-grandfather, John V Palaiologos, even traveled to Rome in 1369 to meet the Pope. His uncle, John VIII Palaiologos, attended a meeting in Florence in 1438-1439. At this meeting, a "union of the churches" was announced, meaning the Orthodox and Catholic churches would become one. However, most people in the Byzantine Empire didn't like this idea. They felt it was a betrayal of their faith, so the union was never fully put into practice.

Andreas's Life

Early Years and New Titles

The last Byzantine Emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, died defending Constantinople from the Ottomans on May 29, 1453. Andreas was born just four months earlier, on January 17, 1453. After Constantinople fell, Andreas's family continued to live in the Morea. But constant arguments between his father, Thomas, and his uncle, Demetrios, led to the Sultan invading the Morea in 1460. Thomas and his family escaped to Corfu.

Thomas then went to Rome, where Pope Pius II welcomed him and gave him money. Thomas hoped to get his lands back. In 1465, Thomas asked his children to come to Rome. Andreas, his younger brother Manuel, and their sister Zoe arrived, but their father had already died.

Andreas was 12 years old at the time. The children went to Rome and were cared for by Cardinal Bessarion. Bessarion had also fled the Byzantine Empire. He made sure the children were educated. Andreas stayed in Rome, and Pope Paul II recognized him as the heir of Thomas and the Despot of the Morea. Andreas also became a Roman Catholic.

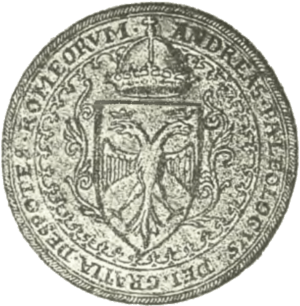

At first, Andreas's seal showed the double-headed eagle of the emperors and the title "Despot of the Romans". But later, he started calling himself the "Emperor of Constantinople". He first used this title on April 13, 1483. He even gave a Spanish nobleman permission to use the Palaiologos family's symbols.

Money Problems

Andreas's money problems began after Cardinal Bessarion died in 1472. By 1475, when he was 22, Andreas started offering to sell his claims to the imperial thrones. He wrote letters to several rulers, hoping to find someone who would pay the most.

His younger brother Manuel also had money troubles. Manuel left Rome and traveled around Europe, looking for a job as a soldier. Since he didn't find good offers, Manuel surprised everyone by going to Constantinople in 1476. He met Sultan Mehmed II, who gave him a good pension for the rest of his life.

The main reason for Andreas's money problems was that the Pope kept reducing the money they gave him. His father, Thomas, used to get 300 ducats a month, plus 200 more from the cardinals. Andreas and Manuel were supposed to share this, but the cardinals stopped paying extra. So, they only got 150 ducats each.

After Bessarion died, it got even worse. The Pope cut Andreas's pension in half, giving him only 150 ducats a month. This amount kept getting smaller over the years. By 1492, he was only getting 50 ducats a month. Andreas also had to support the people who worked for him, which made things even harder.

Andreas lived in a house in Rome. He married a Roman woman named Caterina. In 1480, he traveled to Russia to visit his sister Zoe (who was now called Sophia) to ask for money. Sophia later complained that she had given him all her jewels.

Plans to Fight the Ottomans

Like his father, Andreas actively tried to get the Byzantine Empire back. In 1481, he planned to lead an army against the Ottomans. At that time, the Ottomans' control over the Morea was not strong. Andreas went to southern Italy, which was a good place to start an attack on Greece. He received money from Ferdinand I, the King of Naples.

Andreas hired soldiers, including Krokodeilos Kladas, a Greek soldier who had led a revolt against the Ottomans. Pope Sixtus IV also asked bishops in Italy to help Andreas cross the Adriatic Sea. However, Andreas never sailed to Greece.

The plan was canceled for several reasons. The Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II had died, and his sons were fighting over who would rule. This seemed like a good chance to attack. But by October, the new Sultan, Bayezid, had taken control. Also, the Christian countries in Western Europe were not united enough to fight the Ottomans. Most importantly, Andreas didn't have enough money.

Another reason was that Venice, a powerful city-state, didn't want to help Andreas. Venice had recently signed a peace treaty with the Ottomans and didn't want to fight them again. Andreas did try one more time to take back the Morea in 1485, but it also failed.

Selling the Imperial Title

In 1490, Andreas traveled to Moscow again, but he wasn't welcomed there. So, he went to France instead, where King Charles VIII treated him very well. Charles paid for all of Andreas's travel costs and gave him extra money. Andreas and Charles talked a lot about a crusade against the Ottomans. In 1492, Andreas visited England, but King Henry VII was not as generous.

In the 1490s, King Charles VIII of France was planning a crusade against the Ottomans. A French cardinal, Raymond Peraudi, wanted Charles to focus on fighting the Ottomans instead of getting involved in Italian politics. So, Peraudi worked out a deal with Andreas.

Andreas agreed to give up his titles as Emperor of Constantinople and other claims. In return, he would receive 4300 ducats every year, with 2000 ducats paid right away. He was also promised a personal guard of 100 cavalrymen and lands that would give him an income of 5000 ducats a year. Most importantly, Charles promised to use his army to take back the Despotate of the Morea for Andreas. If Andreas got his ancestral lands back, he would pay Charles a small yearly tax. Charles also promised to ask the Pope to increase Andreas's pension.

This deal wasn't just about money for Andreas. He kept the title of Despot of the Morea and hoped Charles would be a powerful champion against the Ottomans. The documents for this agreement were signed on November 6, 1494. The Pope probably knew about it and supported it, hoping it would lead to a crusade against the Ottomans.

Charles accepted the deal but didn't go to fight the Ottomans right away. He first focused on conquering Naples in Italy. Charles's plans caused concern in Constantinople, and the Sultan started preparing his defenses.

Charles's crusade plans were delayed when he got into conflicts in Italy. Then, a major setback happened when Cem Sultan, the Ottoman Sultan's brother and a rival, died. Cem was supposed to play a key role in the crusade. With Cem's death and other European states forming a league against Charles, the crusade plans were slowly abandoned.

When Charles died in 1498, Andreas claimed his imperial titles again. Since Charles had not fulfilled the conditions of the deal (like getting the Morea back for Andreas), the sale was seen as no longer valid. Church officials recognized Andreas's titles again, calling him "Emperor of the Greeks" or "Emperor of Constantinople."

Later French kings, like Louis XII and Francis I, also continued to use these imperial titles. However, by 1566, King Charles IX stopped using the title, saying it was "not more eminent than that of a king."

Later Life and Death

After the crusade plans failed, Andreas was again short of money. A bishop wrote that Andreas and his group looked poor, wearing rags instead of the fancy clothes he used to wear. Still, Andreas remained an important person in Rome. He was part of Pope Alexander VI's close group and even served in the Pope's honor guard.

Andreas died in Rome in June 1502, still in poverty. In his will, he gave his claim to the imperial title to Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, the rulers of Spain. He hoped that the Spanish monarchs, who had recently won battles, would launch a crusade to take back the Peloponnese and Constantinople. However, neither Ferdinand nor Isabella, nor any later Spanish ruler, ever used the title.

Pope Alexander VI gave Andreas's widow, Caterina, money to pay for his funeral. Andreas was buried with honor in St. Peter's Basilica, next to his father Thomas. Their graves survived because they were in Rome, unlike the tombs of other emperors in Constantinople, which were destroyed by the Ottomans. However, modern attempts to find their exact graves in the Basilica have not been successful.

Possible Descendants

It is generally believed that Andreas did not have any children who survived. However, some historians think that Constantine Palaiologos, a commander in the Papal Guard who died in 1508, might have been Andreas's son.

Russian records mention a daughter named Maria Palaiologina, who is not mentioned in Western sources. She was supposedly married to a Russian nobleman by her aunt Sophia (Andreas's sister). There is also an old Roman tombstone from 1487 that mentions "Lucretia, daughter of Andreas Palaiologos," but she was 49 when she died, so she couldn't have been the daughter of this Andreas.

In 1499, a duke in Milan mentioned sending "Don Fernando, son of the Despot of the Morea" to the Ottomans. This Fernando might have been another son of Andreas. After Andreas's death, Fernando did claim the title Despot of the Morea, but he didn't have much impact on history.

Another person, Theodore Paleologus, who lived in England in the 1600s, claimed to be a descendant of Thomas Palaiologos. He might have been a descendant of Andreas, but his family line is not clear. His last known descendant disappeared in the late 1600s.

In the late 1500s, a religious scholar named Jacob Palaeologus claimed to be Andreas Palaiologos's grandson. Jacob traveled across Europe, boasting about his royal family. However, his religious views caused problems with the Roman church, and he was executed in 1585. Jacob had children, but not much is known about them. One of his sons, Theodore, lived in Prague in 1603 and also claimed to be a prince, but he was found to be a fraud.

Images for kids

-

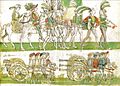

The French troops and artillery of Charles VIII entering Naples in 1495

See also

In Spanish: Andrés Paleólogo para niños

In Spanish: Andrés Paleólogo para niños