Francisco de Quevedo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francisco Gómez de Quevedo

|

|

|---|---|

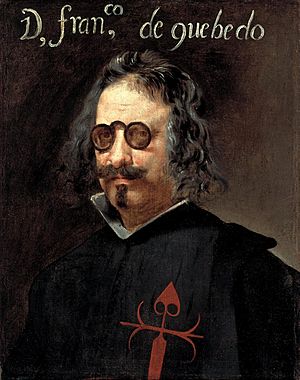

Francisco de Quevedo, Juan van der Hamen, 17th century (Instituto Valencia de Don Juan)

|

|

| Born | Francisco Gómez de Quevedo y Santibáñez Villegas 14 September 1580 Madrid, Spain |

| Died | 8 September 1645 (aged 64) Villanueva de los Infantes, Spain |

| Occupation | Poet and politician |

| Language | Spanish |

| Alma mater | Universidad de Alcalá |

| Period | Spanish Golden Age |

| Genres | Poetry and novel |

| Literary movement | Conceptismo |

| Signature | |

|

|

Francisco Gómez de Quevedo y Santibáñez Villegas (born September 14, 1580 – died September 8, 1645) was an important Spanish nobleman, politician, and writer. He lived during the Baroque period, a time of rich art and literature.

Quevedo was one of the most famous Spanish poets of his era. He had a big rivalry with another poet, Luis de Góngora. Quevedo's writing style was called conceptismo. This style was very different from Góngora's, which was known as culteranismo.

Contents

About Quevedo's Life

Francisco de Quevedo was born in Madrid, Spain, on September 14, 1580. His family were hidalgos, which meant they were part of the lower nobility.

His father, Francisco Gómez de Quevedo, worked for Maria of Spain. She was the daughter of Emperor Charles V. His mother, María de Santibáñez, was a lady-in-waiting to the queen. So, Quevedo grew up around important people at the royal court.

Quevedo was very smart, but he had some physical challenges. He had a club foot and was very nearsighted. He often wore special glasses called pince-nez. In fact, in Spanish, these glasses are sometimes called quevedos because of him!

He became an orphan by the age of six. Despite this, he went to the Imperial School in Madrid. Then, he studied at the Alcalá de Henares university from 1596 to 1600. He also taught himself philosophy, old languages like Greek and Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, French, and Italian.

In 1601, Quevedo moved to Valladolid with the royal court. There, he studied theology, which is the study of religion. He wrote a book later in life called Providencia de Dios (God's Providence) against atheism.

Around this time, he started to become known as a writer. Some of his poems were put into a collection called Flores de Poetas Ilustres in 1605. He also wrote an early version of his famous novel, Vida del Buscón. This book was a picaresque novel, a type of story about a clever but often dishonest hero.

The court moved back to Madrid in 1606, and Quevedo followed. He became friends with other famous writers like Miguel de Cervantes and Lope de Vega.

Quevedo's Rivals

Quevedo had many rivals. One was the writer Juan Ruiz de Alarcón. Quevedo often made fun of Alarcón's appearance. He also argued with Juan Pérez de Montalbán, a bookseller's son. Quevedo even wrote a funny piece about him called La Perinola.

In 1608, Quevedo had a duel with a fencing master named Luis Pacheco de Narváez. Quevedo made fun of Pacheco's work. They stayed enemies for a long time. Quevedo even made fun of this duel in his novel Buscón.

Quevedo could be very quick to act. Once, in a church, he saw a man hit a woman. Quevedo grabbed the man and took him outside. They started fighting with swords. Quevedo injured the man, who later died. Because of this, Quevedo had to hide for a while at the palace of his friend, Pedro Téllez-Girón, 3rd Duke of Osuna.

His biggest rival was the poet Luis de Góngora. Quevedo wrote many sharp, funny poems making fun of Góngora. He even wrote a sonnet called A una nariz (To a Nose) that made fun of Góngora's large nose. It starts with funny lines like: "There was a man glued to a nose, / there was a superlative nose..."

Working with the Duke of Osuna

Quevedo became very close to Pedro Téllez-Girón, 3rd Duke of Osuna. The Duke was a powerful statesman and general. Quevedo went with him to Italy in 1613 as his secretary. He traveled to places like Nice and Venice. He helped the Duke become the Viceroy of Kingdom of Naples in 1616.

Quevedo then returned to Italy with the Duke. He helped manage the Viceroyalty's money and even went on some secret missions. For his hard work, he was made a knight of the Order of Santiago in 1618.

Time Away from Court

In 1620, the Duke of Osuna lost his power. Because of this, Quevedo also lost his important position and was sent away to Torre de Juan Abad. His mother had bought this land for him. However, the people there did not want him as their lord. This led to a long legal fight that Quevedo did not win until after his death.

During this time away, Quevedo wrote some of his best poetry. He found comfort in the ideas of Stoicism, a philosophy that teaches calmness and wisdom. He studied the works of Seneca, a famous Stoic philosopher.

When Philip IV became king in 1621, Quevedo was allowed to return to court. He became involved in politics again, working under the new minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares. Quevedo traveled with the young king and wrote interesting letters about their trips.

He also tried to get control over his writings. Some booksellers were publishing his works without his permission. He wanted to publish a proper collection of his works, but it never happened during his lifetime.

Quevedo's career at court continued. In 1632, he became the king's secretary, which was a very high position.

In 1634, his friend, the Duke de Medinaceli, made Quevedo marry Doña Esperanza de Aragón. She was a widow with children. But the marriage only lasted about three months. During these years, Quevedo wrote many new works.

Arrest and Final Years

In 1639, Quevedo was arrested. His books were taken away. He was sent to the convent of San Marcos in León. In the monastery, Quevedo spent his time reading. He wrote a letter to a friend describing his daily life in prison. He said he would pray and then read "good and bad authors; because there is no book, despicable as it can be, that does not contain something good..."

Quevedo was very weak and sick when he was released in 1643. He decided to leave the royal court for good and went back to Torre de Juan Abad. He died on September 8, 1645, in the Dominican convent of Villanueva de los Infantes.

Quevedo's Writing Style

Quevedo used a writing style called conceptismo. This name comes from the Spanish word concepto, which means a clever idea or thought. Conceptismo is known for its fast rhythm, clear language, simple words, clever comparisons, and wordplay. It packs many meanings into a few words. This style could be used for deep philosophical ideas or for sharp, funny jokes. Quevedo and Baltasar Gracián were masters of this style.

Here is an example of conceptismo from one of Quevedo's sonnets, ¡Ah de la vida!:

- Ayer se fue, mañana no ha llegado,

- Hoy se está yendo sin parar un punto;

- Soy un fue, y un será y un es cansado.

This translates to:

- Yesterday is gone, tomorrow hasn't arrived,

- Today is leaving without stopping for a moment;

- I am a was, and a will be, and a tired is.

Quevedo's Works

Poetry

Quevedo wrote a huge amount of poetry. His poems were not published as books during his lifetime. His poetry often showed a very critical and sometimes harsh view of people. But even with his funny and satirical poems, Quevedo was mostly a serious poet who wrote beautiful love poems.

His poetry shows how smart he was and how much he knew. He had studied many languages, including Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Arabic, French, and Italian. His poems covered many topics, from funny stories and myths to love and deep thoughts.

Quevedo often criticized people who were greedy. He also made fun of apothecaries (old-time pharmacists) who were known for selling bad medicines.

His love poems include works like Afectos varios de su corazón, fluctuando en las ondas de los cabellos de Lisi (Several Reactions of his Heart, Bobbing on the Waves of Lisi's Hair). Even though some people say Quevedo was not fond of women, his love poems show how much he could admire them.

Quevedo also used themes from Greek mythology in his works. For example, in his poem To Apollo chasing Daphne, he adds funny and satirical parts to the myth.

He even wrote a poem imagining a piece of Columbus's ship speaking about its journey to the New World.

Novels

Quevedo wrote only one novel, the picaresque story Vida del Buscón, often called El Buscón. The full title is Historia de la vida del Buscón, llamado Don Pablos, ejemplo de vagamundos y espejo de tacaños. It was published in 1626 and tells the story of a clever character named Pablos. This novel was very popular, even in English, and was translated many times.

Theological Works

Quevedo wrote about 15 books on religious and spiritual topics. These include La cuna y la sepultura (1612; The Cradle and the Grave) and La providencia de Dios (1641; The Providence of God).

Literary Criticism

His works on literary criticism include La culta latiniparla (The Craze for Speaking Latin) and Aguja de navegar cultos (Compass for Navigating among Euphuistic Reefs). Both of these books were written to criticize the culteranismo style of writing, which he disliked.

Satirical Works

Quevedo's satirical works include Sueños y discursos, also known as Los Sueños (1627; Dreams and Discourses). In this work, Quevedo uses a lot of wordplay. It has five "dream-visions." For example, in "The Bedeviled Constable," a police officer is possessed by an evil spirit. But the spirit ends up begging to be removed because the constable is even more evil!

In his Dreams, Quevedo showed his dislike for many different groups of people. He made fun of tailors, innkeepers, doctors, and many others.

He also wrote La hora de todos y la Fortuna con seso (1699). This book has many political, social, and religious jokes. It shows his amazing skill with language and wordplay, using both real and imaginary characters.

Political Works

Quevedo's political writings include La política de Dios, y gobierno de Cristo (1617–1626; "The Politics of the Lord") and La vida de Marco Bruto (1632–1644; The Life of Marcus Brutus). In his writings, he always cared deeply about defending Spain. He believed Spain should be a leading country in the world. He also praised famous Spaniards in literature and war.

Quevedo in Popular Culture

- In Giannina Braschi's novel Yo-Yo Boing!, modern Latin American poets discuss Quevedo's importance to the Spanish Golden Age.

- Quevedo is a main character in the Captain Alatriste books by Arturo Pérez-Reverte. In the movie Alatriste, he was played by Juan Echanove.

- He is also a main character in the novel 1635: The Cannon Law by Eric Flint and Andrew Dennis.

- In the 2013 novel Sudden Death by Alvaro Enrigue, Quevedo plays a tennis match against the Italian painter Caravaggio.

See also

In Spanish: Francisco de Quevedo para niños

In Spanish: Francisco de Quevedo para niños

- Siglo de Oro

- Spanish Literature

- Spanish poetry

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |