Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Spanish American wars of independence | |||||||

Battle of Pueblo Viejo |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,500 (1829) | 3,500 (1829) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 135 killed in combat (1829) | 215 killed in combat (1829) and 1,708 killed by diseases and in combat in the Tampico expedition | ||||||

The Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico were efforts by Spain to take back its former colony, New Spain. These attempts led to several battles between the newly independent Mexico and Spain. The main efforts happened in two periods. The first was from 1821 to 1825, focusing on defending Mexico's waters. The second period had two parts: Mexico's plan to take the Spanish island of Cuba (1826-1828), and the 1829 expedition by Spanish General Isidro Barradas. He landed in Mexico hoping to reclaim the land. Spain never regained control, but these conflicts did hurt Mexico's new economy.

After eleven years of fighting in its War of Independence, Mexico was in a tough spot. There were no clear plans for the new government. Different groups fought for control. Mexico also lacked money to run a huge country and faced threats from inside and from Spanish forces in nearby Cuba.

Contents

Why Spain Tried to Take Mexico Back

Mexican independence officially happened on September 27, 1821, with the Treaty of Córdoba. However, Spain did not agree with this treaty. They said that the Spanish leader in Mexico, Juan O'Donojú, did not have the power to recognize Mexico's independence. This was a big problem for the new nation. No major European countries had yet recognized Mexico's independence. The constant threat of Spain trying to take Mexico back worried the new leaders a lot. To protect itself, the Mexican government made laws on May 13, 1822. These laws allowed them to arrest anyone who worked against Mexico's independence.

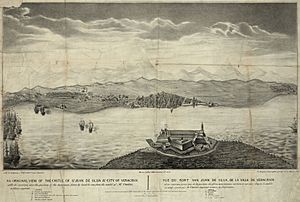

Adding to Mexico's problems, the main port for entering the country, San Juan de Ulúa, was still controlled by Spain.

The Fight for San Juan de Ulúa

General José García Dávila, the Spanish governor in Veracruz, and General Antonio López de Santa Anna were told to hand over the port to Mexico. But on the night before October 26, 1821, General Dávila moved all the cannons, ammunition, 200 soldiers, and over 90,000 pesos to the fortress of San Juan de Ulúa. Soon, the number of Spanish soldiers grew to 2,000. These troops were sent from Cuba to help Spain reconquer Mexico. Mexico did not have the weapons or ships to fight these new forces. So, the first Emperor of Mexico, Agustín de Iturbide, decided to try talking with the Spanish. No agreement was reached, but a tense peace continued.

On September 10, 1822, General Antonio López de Santa Anna arrived to govern Veracruz. This started new talks between Mexican officials in Veracruz and the Spanish in San Juan de Ulúa. These talks became very important, especially when the Spanish government replaced General Dávila with General Francisco Lemaur. The Mexican government knew it needed ships. They decided to build a navy to defeat the Spanish in Ulúa, mainly by blocking their supplies. In 1822, Mexico bought its first ships for the Mexican Navy from the United States and the United Kingdom.

Even with political problems in Mexico, like the end of the Mexican Empire, Mexico still focused on Ulúa. The talks stopped when, on September 25, 1823, the Spanish bombed the port of Veracruz. This caused more than 6,000 people to leave the city.

Spanish Surrender at Ulúa

After the Spanish bombed the port, the Mexican government decided to stop the attacks for good. Mexico did not have a strong navy yet. But on October 8, 1823, they planned to block San Juan de Ulúa. The Secretary of War and Navy, José Joaquín de Herrera, spoke to the First Congress of Mexico. He stressed how urgent it was to get more warships to block and attack the Spanish troops in the fortress.

On January 28, 1825, General Francisco Lemaur was replaced as commander of San Juan de Ulúa by José Coppinger. On July 27, 1825, Pedro Sainz de Baranda was made commander of the Navy in Veracruz. He quickly started to organize the ships to block San Juan de Ulúa.

The blockade worked well. The Spanish forces, who received little help from Havana, were forced to give up. Coppinger asked to stop fighting and to discuss their surrender. The fighting, which began on October 26, 1821, ended when the Mexican Navy defeated the last Spanish stronghold in Mexico on November 23, 1825.

Protecting the Seas and Looking Towards Cuba

Even after Mexico won against the last Spanish base in Ulúa, Spain still refused to recognize the Treaty of Córdoba. This meant they did not recognize Mexico's independence.

The Mexican government, led by Guadalupe Victoria, realized that Spain was still a threat. Spain could use Cuba as a base to launch another attack to take back Mexico. Lucas Alamán, who was Mexico's Minister of Foreign Affairs, understood the danger from Spanish military forces in Cuba. Since 1824, Alamán believed Mexico should take Cuba. He argued that "Cuba without Mexico is aimed at imperialist yoke; Mexico without Cuba is a prisoner of the Gulf of Mexico." He thought that Mexican forces, with help from countries like France or England, could defeat the Spanish in Cuba. England was the first European country to recognize Mexico's independence on July 16, 1836.

The United States, however, wanted Spain to keep control of Cuba. To help its own goals for the island and prevent Spain from reconquering Mexico, the Mexican government hired Commodore David Porter from the United States. He was to command the Mexican navy in attacks on Spanish ships patrolling around Cuba. This was to protect Mexico's waters and ensure its independence continued. So, Mexican ships began patrolling Spanish waters. This led to the unsuccessful Battle of Mariel on February 10, 1828. In this battle, Porter commanded the ship Guerrero, which had 22 guns and was one of the best in the small Mexican Navy. Porter's son, David Dixon Porter, who later became a hero in the American Civil War, was slightly hurt. He was among those who surrendered and were held in Havana until they could be exchanged. Commodore Porter did not want to risk his son again, so he sent him back to the United States.

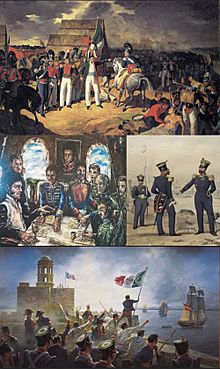

The Battle of Tampico

One year after the Battle of Mariel, Spain made another attempt to reconquer Mexico from Cuba. This confirmed Mexico's suspicions. Spain appointed General Isidro Barradas. He left the port with 3,586 soldiers, calling his group the "Spearhead Division." On July 5, they sailed for Mexico. The Spanish fleet included a main ship called the Sovereign, two frigates, two gunships, and 15 transport ships. Admiral Laborde commanded the fleet.

On July 26, 1829, the fleet reached Cabo Rojo, near Tampico in the state of Tamaulipas. From there, they began their operations on the 27th, trying to land 750 troops and 25 boats. The expedition started moving towards Tampico while the boats were anchored at the Pánuco River. The Battle of Pueblo Viejo, which happened on September 10-11, marked the end of Spain's attempts to conquer Mexico. General Isidro Barradas signed the surrender at Pueblo Viejo. Generals Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, Manuel de Mier y Terán, and Felipe de la Garza were present.

On December 28, 1836, Spain finally recognized Mexico's independence. This happened with the Santa María–Calatrava Treaty, signed in Madrid. Mexico was the first former colony whose independence Spain recognized. The second was Ecuador on February 16, 1840.

See also

In Spanish: Intentos de reconquista española en México para niños

In Spanish: Intentos de reconquista española en México para niños

- History of Mexico

- Reconquista (Mexico)

- List of wars involving Mexico

- Mexican War of Independence

- Spanish American wars of independence

- Spanish occupation of the Dominican Republic

Sources

- GONZÁLEZ PEDRERO, Enrique (1993) País de un solo hombre: el México de Santa Anna México, ed.Fondo de Cultura Económica, ISBN: 978-968-16-3962-4 URL accessed September 27, 2009

- Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, Asociación de amigos del Museo Nacional de las Intervenciones, Museo Nacional de las Intervenciones (2007) Las intervenciones extranjeras en México 1825-1916, Cuernavaca, ed. Servicios Gráficos de Morelos, ISBN: 978-968-03-0283-3

- RUIZ GORDEJUELA URQUIJO, Jesús (2006) La expulsión de los españoles de México y su destino incierto, 1821-1836 Sevilla, ed.Universidad de Sevilla ISBN: 978-84-00-08467-7 URL accessed September 27, 2009

- SIMS, Harold (1984) La reconquista de México: la historia de los atentados españoles, 1821-1830, México, ed. Fondo de Cultura Económica, URL accessed September 27, 2009

- SIMS, Harold (1990) The Expulsion of Mexico's Spaniards, 1821–1836, University of Pittsburgh Press.

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |