Eugenio Espejo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Eugenio Espejo

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | February 21, 1747 |

| Died | December 28, 1795 (aged 48) |

| Occupation | Writer, lawyer, physician |

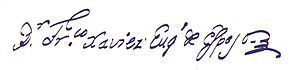

Francisco Javier Eugenio de Santa Cruz y Espejo (born February 21, 1747, in Quito – died December 28, 1795) was a very important person in colonial Ecuador. He was a doctor, writer, and lawyer. He was also a mestizo, meaning he had mixed European and Indigenous heritage.

Espejo was known for being a pioneer in medicine and a great writer. He is also famous for inspiring the movement for independence in Quito. Many people see him as one of the most important figures from that time in Ecuador. He was also Quito's first journalist and a leader in public health.

As a journalist, he shared new ideas from the Age of Enlightenment. As a health expert, he wrote an important book about how to keep people healthy. This book even talked about tiny living things (microorganisms) and how diseases spread.

Espejo was also known for his funny and sharp writings, called satires. These writings were based on the ideas of the Enlightenment. He used them to criticize the lack of education in Quito. He also spoke out against how the economy was managed and the corruption of leaders. Because of these writings, he was often in trouble and was even put in jail before he died.

Contents

Life in Colonial Quito

The Royal Audiencia of Quito was a part of the Spanish Empire. It was set up by King Philip II of Spain in 1563. This court helped the Spanish Crown control lands that are now part of Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, and Brazil. Its main city was Quito. The Audiencia also managed relationships between Spanish people and Indigenous groups.

By the 1700s, Quito faced many economic problems. There were not enough roads, which made communication difficult. Textile factories, called obrajes, used to provide many jobs. But they started to decline because of smuggled European goods and natural disasters. Large farms, called haciendas, replaced the factories. These farms often exploited the Indigenous people.

Education in Quito also suffered after the Jesuit priests were expelled. Not enough educated people were left to teach. Most people could not read or write well. Those who went to university learned mostly by memorizing old ideas. This meant people had few new ideas to share. In 1793, Quito had only two doctors, and Espejo was one of them. Most sick people relied on traditional healers.

During this time, people in Quito often judged others based on their race. Society was divided into different groups based on where people came from. This meant a person's worth could be harmed by racial prejudice. Poverty was also increasing, especially for poorer people. Many women had to find quick places to live, like convents. This also explains why there were so many priests in Quito. Often, men became priests not because they felt called to it, but to solve their money problems and gain respect.

Eugenio Espejo's Life Story

Early Years

Eugenio Espejo was baptized on February 21, 1747. Most historians believe his father was Luis de la Cruz Chuzhig. He was an Indigenous man from Cajamarca. His mother was Maria Catalina Aldás, a mulatta (mixed African and European heritage) from Quito. However, some historians think his mother might have been white. This is because his parents' marriage and his birth were recorded in the books for white people.

Eugenio had two younger siblings, Juan Pablo and María Manuela. Even though his family didn't have much money, Espejo got a good education. He learned medicine by working with his father at the Hospital de la Misericordia. He said he learned "by experience, which cannot be known without studying with pen in hand."

Despite facing racial discrimination, he became a doctor in 1767. He also studied law and graduated in 1772. After that, we don't know much about him until 1778. That year, he wrote a sermon that caused some debate.

His Work in the Royal Audiencia

Challenging Authority with Words

Between 1772 and 1779, Espejo often challenged the leaders of the colony. They believed he was behind many funny and critical posters. These posters were put on church doors and other buildings. They often attacked the leaders, the clergy, or other things he disagreed with. Even though these posters are lost, Espejo's own writings suggest he wrote them.

In 1779, a satirical manuscript called El nuevo Luciano de Quito (The New Lucian of Quito) was passed around. It was signed with a fake name, "don Javier de Cía, Apéstegui y Perochena," which was Espejo. This work made fun of the problems in Quito society. It especially criticized the corruption of leaders and the lack of education. Using a fake name was common during the Enlightenment. It helped Espejo stay anonymous and hide his mixed racial background. This was important in a society that valued white people more.

From 1779 onwards, Espejo kept writing satires against the government. In 1780, he wrote Marco Porcio Catón (Marcus Porcius Cato), using another fake name, "Moisés Blancardo." In this work, he mocked his critics. In 1781, he wrote La ciencia blancardina, which was a follow-up to Nuevo Luciano. Because of his writings, by 1783, he was seen as "rebellious and troublesome." To get rid of him, the authorities made him chief doctor for a scientific trip. Espejo tried to refuse and even tried to run away. He was caught and sent back as a "criminal." But he was not punished much.

Time Away from Quito

In 1785, the town council asked him to write about smallpox. This was a big health problem in Quito. Espejo used this chance to write his best work, Reflexiones acerca de un método para preservar a los pueblos de las viruelas (Reflections about a method to preserve the people from smallpox). In it, he criticized how the Audiencia handled public health. This book is a valuable source about health conditions in colonial America.

Reflexiones was sent to Spain. But instead of praise, Espejo made enemies. His work criticized doctors and priests in charge of public health for being careless. So, he was forced to leave Quito.

On his way to Lima, he stopped in Riobamba. There, some priests asked him to write a response to a report. This report accused the priests of abusing Indigenous people to get their money. Espejo gladly accepted. He wanted to get back at the report's author, Ignacio Barreto, and others who had caused him trouble before. He wrote Defensa de los curas de Riobamba (Defense of the clergy of Riobamba). This was a detailed study of Indigenous life in Riobamba and a strong attack on Barreto's report.

In March 1787, he continued attacking his enemies with eight satirical letters. These were called Cartas riobambenses. His enemies then reported him to the President of the Royal Audiencia. On August 24, 1787, Espejo was arrested. He was accused of writing El Retrato de Golilla, which made fun of King Charles III of Spain. He was sent to Quito. From prison, he sent three requests to the Court in Madrid. The King ordered his case to be sent to the Viceroy of Bogotá. Espejo was sent to Bogotá to defend himself.

In Bogotá, he met Antonio Nariño. He started to develop his ideas about freedom. In 1789, one of his friends, Juan Pio Montufar, arrived in Bogotá. Together, they got approval to create the Sociedad Patriótica de Amigos del País de Quito (Patriotic Society of Friends of the Country of Quito). This was a private group that aimed to improve society. Espejo successfully defended himself. On October 2, 1789, he was set free. On December 2, he was told he could return to Quito.

Last Years

In 1790, Espejo went back to Quito to promote the "Sociedad Patriótica." On November 30, 1791, a branch was set up. He was chosen as its director. In the same year, he became the director of the first public library, the National Library. This library had forty thousand books left by the Jesuits after they were expelled.

The main goal of the Society was to improve Quito. Its 24 members met weekly to discuss farming, education, politics, and social problems. They also promoted science. The Society started Quito's first newspaper, Primicias de la Cultura de Quito. Espejo published it starting on January 5, 1792. Through this newspaper, ideas about freedom, already known elsewhere, spread among the people of Quito.

On November 11, 1793, King Charles IV of Spain closed the society. The newspaper also stopped. Espejo had to work as a librarian. Because of his ideas, he was put in prison on January 30, 1795. He was only allowed to leave his cell to treat patients as a doctor. On December 23, he was allowed to go home. He died there on December 28 from a disease he got in prison. His death certificate was recorded in the book for Indigenous people, mestizos, and mulattoes.

Who Was Eugenio Espejo?

Eugenio Espejo taught himself many things. He was proud that he read every book he could find. If he didn't read a book, he would learn by observing nature. He believed that education was the main way for people to develop. He understood that reading was key to forming one's own thoughts. This led him to criticize the existing system, based on what he saw and the laws of his time.

Through his writing, Espejo wanted to educate people and awaken a spirit of change. He believed in equality between Indigenous people and criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the Americas). He also supported women's rights, though he didn't fully develop these ideas. He had a very advanced understanding of science for his time. Even though he never traveled abroad, he understood how tiny living things (microorganisms) caused diseases.

When he was arrested, people rumored it was because he supported the "godless" ideas of the French Revolution. However, Espejo understood the difference between the French Revolution's actions and its anti-religious spirit. He never lost his Catholic faith. He criticized the decline of the clergy, but never the Church itself. Eugenio Espejo had a strong desire for knowledge. He wanted to use his work to improve a society that he felt was behind the times, influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment.

Espejo's Ideas

Thoughts on Education

Espejo's first three works aimed to improve thinking in Quito. El Nuevo Luciano de Quito made fun of the old-fashioned education system run by the clergy. Espejo said that people in Quito were used to flattery. They admired any preacher who could quote the Bible in a showy but empty way. Marco Porcio Catón showed how little the so-called intellectuals of Quito actually knew. La ciencia blancardina said that the clergy's education system led to ignorance. All three works caused a lot of discussion.

Through these books, Espejo shared ideas from European and American scholars. Because of him, many religious groups changed their teaching programs. Espejo disliked the fake intellectuals who misled the people of Quito. He felt they ignored truly knowledgeable people.

Espejo especially criticized the Jesuits. He said they taught ethics as good manners, not as a science. He complained about the relaxed system for training priests in Quito. He felt it made students lazy. As a result, priests didn't truly understand their duties and didn't want to study. In El Nuevo Luciano de Quito, he complained about the many fake doctors. In La ciencia blancardina, he continued to attack these fakes and also clerics who practiced medicine without proper training.

Thoughts on Religion

In 1780, Espejo wrote his first work on religious topics. It was a letter called Carta al Padre la Graña sobre indulgencias (Letter to Father la Graña about indulgences). In this work, he discussed indulgences in the Catholic Church. The letter showed his deep knowledge of religious teachings. He looked at the history of indulgences and how they developed. He also mentioned rules and official papers about abuses of indulgences. In this work, Espejo strongly supported the Pope's authority.

On July 19, 1792, Espejo wrote another letter. It was called Segunda carta teológica sobre la Inmaculada Concepción de María (Second theological letter about Mary's Immaculate Conception). He wrote it because the Holy Office asked him to. This letter discussed the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Again, this work showed his deep understanding of this religious topic. It also showed how important it was in the 1700s.

Espejo also wrote several sermons. They were known for being simple. An Ecuadorian historian, Federico González Suárez, thought these sermons were worth studying. He noted that they lacked an "evangelic spirit." Overall, Espejo can be seen as a deeply religious man.

Thoughts on Money and Trade

Starting in 1785, Espejo became interested in the well-being of his community. He cared about Quito's success. His works from 1785 to 1792 clearly show the influence of Enlightenment thinkers. Espejo adapted their ideas to local conditions. Many thinkers realized how powerful economics was. Espejo, influenced by thinkers like Adam Smith, wanted reforms in trade and farming. He especially cared about protecting and properly using land. To promote these ideas, he founded the Escuela de la Concordia (School of Concord).

His works, Voto de un ministro togado de la Audiencia de Quito and Memorias sobre el corte de quinas, opposed a proposed monopoly on quinine production. The Crown wanted this monopoly to stop the destruction of the cinchona tree and to make more money. Memorias was dedicated to Fernando Cuadrado, who also opposed the monopoly.

Espejo divided his study of cinchona into four parts. In the first part, he argued that the monopoly would leave workers jobless. It would also mean losing money invested in cinchona trees. In the second part, he suggested developing natural products from each region for export. For example, Chile should focus on wines, and Argentina on leather. In the third part, he showed that many workers benefited from the quinine industry. Without it, there would be unemployment and unrest. He said the Crown should appoint officials to manage cinchona tree farming properly, including planting new trees. In the fourth part, he made recommendations, such as the need to stop hostility from Indigenous people in the cinchona tree region.

Work as a Lawyer

His Defensa de los curas de Riobamba was a response to a report by Ignacio Barreto. This report accused the clergy in Riobamba of many bad practices. For example, it said that too many religious celebrations harmed the Catholic faith, farming, and the Crown's interests. It also claimed that priests demanded money from Indigenous people for church entry and ceremonies. It said priests in Riobamba were immoral and their sermons were hard for Indigenous people to understand.

Espejo attacked Barreto's report in three ways. First, he claimed Barreto was not smart enough to write it. Then, he argued that the accusations were exaggerated half-truths or complete lies. Finally, he said Quito's economic problems could not be solved by exploiting its people. Instead, they needed planning and using the region's natural resources.

Espejo realized the charges against the clergy were serious. So, he focused on destroying Barreto's trustworthiness. He hinted that Barreto's own behavior was bad because of his excessive tax collecting. He also said the real author of the report was José Miguel Vallejo, whom he called an immoral man who disliked the clergy. Thus, Espejo claimed the report should not be believed.

It seems Espejo was more interested in attacking his personal enemies in this work than just defending the clergy. Still, his skill as a lawyer can be seen in his Representaciones (Representations). These documents helped him get freed after his arrest in 1787. In them, he declared his loyalty to the Crown. He also talked about how unfair his imprisonment was and explained his writing goals. This led to his main point: denying he wrote El Retrato de Golilla.

Scientific Work

The Spanish Crown cared a lot about public health. Diseases were always a problem in the colonies. Town councils spent money to bring doctors or health equipment from other parts of the Americas. Doctors often wrote reports about the health conditions in different parts of cities. As a scientist, Eugenio Espejo showed he knew about the latest scientific discoveries in Europe and the Americas. Most of his ideas and suggestions in his medical works came from sources like the Mémoires of the French Academy of Sciences.

Quito was especially worried about preventing smallpox. The President of the Audiencia, Villalengua, gathered all of Quito's doctors. They discussed applying methods suggested by the Spanish scientist Francisco Gil. Espejo was asked to write his Reflexiones acerca de un método para preservar a los pueblos de las viruelas. This work, finished on November 11, 1785, had two parts. The first dealt with preventing smallpox in Quito. The second dealt with problems in getting rid of it. Espejo's knowledge of inoculations and quarantining smallpox victims was very advanced for his time.

Reflexiones suggested using proven methods supported by doctors. It argued against the common belief that separating and destroying contaminated clothes was impossible. It also promoted personal hygiene among the people of Quito. Espejo tried to convince people about the dangers of smallpox. He understood the European medical ideas about contagious diseases. He warned against the wrong belief that smallpox was spread by bad air. Citing the English doctor Thomas Sydenham, he suggested building an isolated country house as a hospital.

When discussing sanitation, Espejo noted that the city's hospital, monasteries, and churches were dirty. He said this would surely lead to future epidemics. He disagreed with burying the dead inside churches. Instead, he suggested burying them outside the city in a graveyard chosen by the Church. Finally, he criticized how the hospital was managed by the Bethlehemites. He said their methods were old-fashioned and they provided poor service. The hospital staff reacted badly to this. Espejo lost the friendship of his mentor, José del Rosario.

Eugenio Espejo's Impact

Espejo is seen as the person who started the independence movement in Quito. He died in 1795, but his ideas strongly influenced three close friends: Juan Pío Montúfar, Juan de Dios Morales, and Juan de Salinas. They, along with Manuel Rodriguez Quiroga, started the revolutionary movement on August 10, 1809, in Quito. On that day, the city declared its independence from Spain.

Espejo published Quito's first newspaper. Because of this, he is considered the founder of Ecuadorian journalism. He is also seen as Ecuador's first literary critic. According to a Spanish scholar, Espejo's Nuevo Luciano is the oldest critical work written in South America.

His influence can also be seen in Ecuadorian thought in general. His work has been a major influence. In education, he promoted new ideas, like creating good citizens instead of just teaching facts. In science, he was one of the two most important scientists of colonial Ecuador, along with Pedro Vicente Maldonado. Espejo looked closely at life in colonial Quito. He saw the poverty of its people and their lack of good education. He also spoke out against the corruption of the colonial leaders.

Since 2000, Espejo's image has been on the front of Ecuador's 10 centavo coin.

Works by Eugenio Espejo

- Sermones para la profesión de dos religiosas (1778)

- Sermón sobre los dolores de la Virgen (1779)

- Nuevo Luciano de Quito (1779)

- Marco Porcio Catón o Memorias para la impugnación del nuevo Luciano de Quito (1780)

- Carta al Padre la Graña sobre indulgencias (1780)

- Sermón de San Pedro (1780)

- La Ciencia Blancardina (1781)

- El Retrato de Golilla (Attributed, 1781)

- Reflexiones acerca de un método para preservar a los pueblos de las viruelas (1785) Online version (Spanish)

- Defensa de los curas de Riobamba (1787)

- Cartas riobambenses (1787)

- Representaciones al presidente Villalengua (1787)

- Discurso sobre la necesidad de establecer una sociedad patriótica con el nombre de "Escuela de la Concordia" (1789)

- Segunda carta teológica sobre la Inmaculada Concepción de María (1792)

- Memorias sobre el corte de quinas (1792)

- Voto de un ministro togado de la Audiencia de Quito (1792) Online version (Spanish)

- Sermón de Santa Rosa (1793)

See also

In Spanish: Eugenio Espejo para niños

In Spanish: Eugenio Espejo para niños